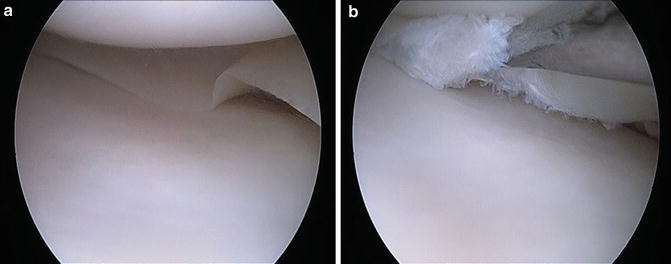

Fig. 9.1

Arthroscopic picture showing a stable, vertical longitudinal tear in the posterior third of the lateral meniscus which does not extend anterior to the popliteal tendon

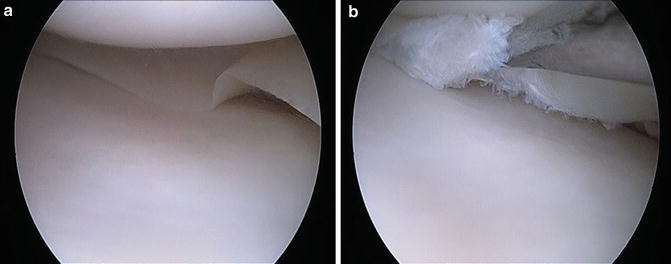

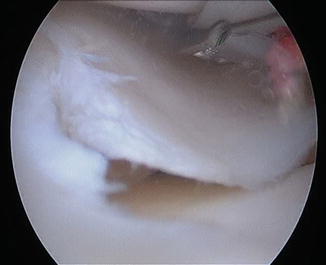

Fig. 9.2

A vertical longitudinal tear of the lateral meniscus that extends anterior to the popliteus (a) and can be displaced into the intercondylar notch with a probe (b). The same meniscus tear is shown after suture repair (c)

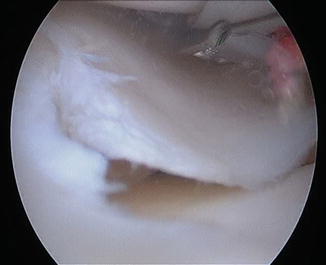

Fig. 9.3

An avulsion of the posterior attachment of the lateral meniscus

The medial meniscus also has varying tear patterns that are encountered in unique situations, and medial meniscus tears account for the preponderance of arthroscopies done in the United States. The medial meniscus tears that occur at the time of an ACL injury are very similar to those that occur on the lateral side. They tend to be vertical tears in the posterior third which occur when the tibia and the femur are forcefully compressed the time of the index “pivot” episode. These are usually stable tears and, therefore, may be regarded as somewhat incidental findings at the time of ACL reconstruction. In chronic ACL tears, when the knee is subjected to repeated episodes of instability, medial tears can become larger, rendering them unstable tears that are displaceable into the intracondylar notch [7]. In ACL-intact knees, the pattern of tear is distinctly different. These tears are usually degenerative and will predictably tear in both the vertical and horizontal planes, making repair less likely to succeed.

In this chapter we will discuss the general indications for repair of both the medial and lateral menisci in both the ACL-intact knee and in the ACL-injured knee. It is our hope to guide the reader in making more sound and scientifically based decisions in meniscal tear management.

ACL-Intact Knee

Medial Meniscus Tears in the ACL-Intact Knee

It has been estimated that over 850,000 knee arthroscopies are performed annually in the United States for treatment of meniscus tears [8]. Medial meniscus tears are much more common than lateral meniscus tears, and males are more commonly affected at a rate of approximately 2.5:1 [8]. Degenerative tears are most commonly seen in patients over the age of 40, but they can also be seen in younger patients with a history of sports activities involving repeated deep knee flexion, such as wresting, baseball/softball catching, and volleyball. With time and repetitive motion, the meniscus begins to fail usually first in the horizontal plane. This enables the inferior lamina to displace into the joint, allowing it to become compressed between the tibia and the femur. As the “horizontal cleavage” enlarges, it is prone to catch even more, causing increased symptoms and propagation of the tear (Fig. 9.4). Patients often report pain with squatting and rotation, as these activities cause the meniscus to get caught. These tears usually have an insidious onset of swelling, pain, and catching, and they are not usually attributed to a specific injury.

Fig. 9.4

This medial meniscus appears to be normal (a) prior to placing the probe into the undersurface of the meniscus where the degenerative tear is located. (b) Probing the medial meniscus reveals a vertical tear with a horizontal degenerative component

Several studies have shown higher success rates of medial meniscus repairs that were done at the time of ACL reconstruction compared with repairs done in ACL-intact knees [9–12]. Cannon and Vittori [11] evaluated meniscal healing in 90 repairs done in conjunction with ACL reconstruction and 27 repairs done in ACL-intact knees. They concluded that overall, the success was higher when the repair was done in conjunction with ACL reconstruction (93 %) compared to repairs done in an ACL-intact knee (50 %). It has long been assumed that this success is secondary to the bleeding and growth factors associated with an ACL reconstruction. However, as noted earlier, most tears occurring in ACL-injured knees are sustained to a normal meniscus, whereas tears in an ACL-intact knee are more often degenerative in nature. Without the presence of good quality meniscal tissue to facilitate healing of the repair, a significantly higher failure rate is to be expected.

A distinct type of tear occurs in the posterior third of the medial meniscus and is seen in patients with early degenerative joint disease. These “root avulsion” or posterior horn detachments are especially common in middle-aged females and are discussed elsewhere (Chap. 12) in more detail. Unlike lateral posterior horn tears seen in the setting of acute ACL injury, the medial root avulsion tears have a low propensity for spontaneous healing. Patients commonly complain of a specific injury where they felt a distinct tear or pop, usually when stepping up/down a stair or planting the foot. These tears occur near the posterior horn attachment to the tibia (Fig. 9.5), and they are believed to occur as a result of increasing medial side joint stress secondary to chondral wear and decreasing joint space width. Laboratory studies have shown that when these tears are created in a cadaver and then repaired, they will restore normal joint contact pressures [13, 14]. However, no studies have conclusively shown that repairing these tears can reverse the natural course of joint wear and arthritis when the knee already has degenerative changes visible on radiographs. Lee et al. [15] showed that degenerative tears with a radial component showed more evidence of meniscal extrusion than degenerative tears without a radial component. They also found that the presence of a radial component and the severity of osteoarthritis were predictive of extrusion. They recommended that arthroscopic procedures, particularly meniscus repair, should be cautiously considered in cases of meniscal extrusion [15]. A great number of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans done on patients with radiographic evidence of arthritis of the knee will show this type of tear with the meniscus extruded from the joint. In the presence of moderate to severe degenerative changes, repair of this meniscus tear is not likely to result in elimination of symptoms since patient discomfort is primarily due to the arthritic changes. Lim et al. [16] showed in 2010 that these tears can be treated nonoperatively with a decrease in symptoms, lending credence to the idea that the symptoms these patients experience are at least in part related to the osteoarthritis and not the meniscus tear.

Fig. 9.5

A posterior radial tear of the medial meniscus

However, when Lee et al. [17] examined results of fixation of posterior root tears via a pullout suture technique, they noted that most of their patients were satisfied with their results, showing significant improvement in Hospital for Special Surgery and Lysholm subjective scores. Most impressive is the lack of advancement of degenerative changes seen over a mean follow-up of 31.8 months [17]. Although longer-term follow-up is warranted, this suggests that restoration of hoop stresses to meniscal tissue may serve as a chondral protective agent.

Lateral Meniscus Tears in the ACL-Intact Knee

As mentioned previously, the lateral meniscus has a very different tibial anchoring mechanism than the medial side; specifically, it does not have a significant attachment to the posterior third of the capsule and, subsequently, is more mobile. This increased mobility can predispose the lateral meniscus to result in a displaced bucket-handle tear when more violent torsional stress is applied. Increased forward mobility of the meniscus can predispose to a tissue failure, particularly anterior to the popliteus tendon, and propagation until the meniscus gets “wedged” within the intercondylar notch. This differs from what occurs on the medial side where a bucket-handle medial meniscus tear will usually flip 180° from its normal position when it displaces; the lateral meniscus will simply slide into the notch in its normal planar orientation. Clinically, patients with these tears often present reporting pain after rising quickly from a position with their legs crossed or with their knees in a figure-4 position. Most often, these tears are nondegenerative and, therefore, are amenable to repair (Fig. 9.2). Since the attachment to the capsule is anterior to the popliteus tendon, that is the portion of the tear that needs most attention during repair. The authors prefer an inside-out suture technique, but any system or “fixator” that allows the meniscus to be secured both superiorly and inferiorly will suffice.

The other acute tear pattern commonly seen in the lateral meniscus is a radial tear (Fig. 9.6). These tears are most often seen in the mid-third of the meniscus and are associated with a valgus injury or a valgus rotational injury. As the joint opens medially during valgus loading, the lateral meniscus is compressed and tears in a radial fashion. The fibers of the meniscus are oriented in a parallel and circular pattern creating a hoop. Radial tears disrupt this hoop force and render the meniscus much less effective in dissipating stress. Radial tears of the lateral meniscus are commonly in the white–white zone and, consequently, are usually not amenable to repair. There have been studies advocating for repair of these tears, especially when biologic augmentation is employed. However, it is the authors’ practice to remove the torn portion back to stable fibers in order to prevent tear propagation.

Fig. 9.6

A radial tear of the lateral meniscus

Although relatively uncommon, the meniscus can be developmentally formed aberrantly in the form of a discoid meniscus. These flat, pancake-resembling structures are seen more frequently in Asian populations and are often structurally unsound. Furthermore, a discoid meniscus may tear because its abnormal shape renders it unable to sustain more joint compression. A discoid lateral meniscus is far more common than a discoid medial meniscus. The discoid tear frequently occurs in the structurally abnormal area of the meniscus found directly under the femoral condyle. Consequently, it is not amenable to repair. Instead, it is removed back to the portion of the meniscus which is normal. However, the Wrisberg variant, or detachment of the posterior horn from the posterior capsule, is amenable to repair. Great care must be taken during suturing of these lesions as the posterior horn of the lateral meniscus is directly anterior to the popliteal artery. For inside-out techniques, a contralateral suturing portal must be employed.

Although much less common than degenerative medial meniscus tears, degenerative lateral meniscus tears can occur as well. As with degenerative tears of the medial meniscus, degenerative lateral meniscus tears occur because of attritional changes of the meniscus rather than because of an acute injury. They are often seen in conjunction with degenerative changes in the lateral compartment, and just like on the medial side, the lateral meniscus can be extruded when joint space narrowing is present. Of course, attempts to repair this type of meniscus tear are usually doomed to fail because of the poor quality of the meniscus.

ACL-Deficient Knee

Much research in the last several years has focused on the treatment of meniscus tears that occur with ACL injury. We have known for many years that if the ACL is left untreated, there is a much higher risk of meniscus injury, particularly to the medial meniscus [7]. As a result, there has been increased awareness of the types of injuries that occur with ACL tears and how they should be treated.

Lateral Meniscus Tears in the ACL-Deficient Knee

As stated, several studies have shown that the lateral meniscus is more commonly torn acutely at the time of ACL injury [4, 5]. This is likely because the meniscus becomes trapped between the femur and the tibia during the acute pivoting episode. Most commonly, the tear occurs in the posterior third of the lateral meniscus, which does not have a strong attachment to the surrounding capsule. However, the indications for repair of this lesion are bathed in controversy. In their study of 178 lateral meniscus tears left in situ at the time of ACL reconstruction, Fitzgibbons and Shelbourne [6] found that 52 were posterior horn avulsions, 99 were stable vertical tears of the posterior horn, and 27 were stable non-displaced vertical tears that extended anterior to the popliteus. Several studies have shown that these meniscus tears can be left in situ without risk of retear or further significant injury [6, 18–20]. Often times, the authors will trephinate the portion that is torn if it does not appear to be completely healed at the time of surgery. Trephination has been shown in both animal and clinical studies to promote meniscal healing by creating vascular channels [11, 21, 22]. Since these longitudinal tears are generally stable, there is no need for formal fixation, but stimulation of the surrounding tissue helps promote healing. Shelbourne and Heinrich reported on 43 patients who had trephination of posterior or peripheral lateral meniscus tears at the time of ACL reconstruction and found that none required any additional surgery at a mean follow-up of 6.6 years postoperatively [20].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree