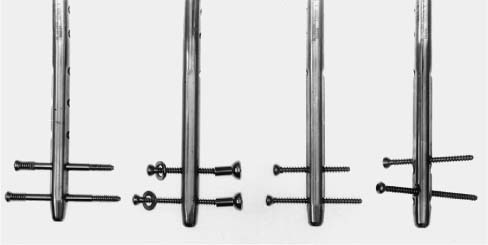

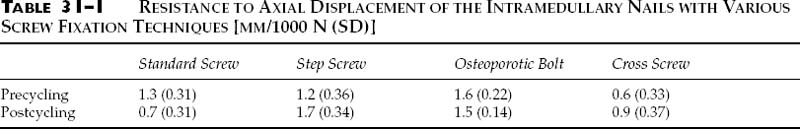

Chapter 31 Intramedullary nailing is a common treatment of diaphyseal fractures.1–3 Its advantages include immediate fracture stabilization with early weight bearing and relative preservation of the soft tissue envelope. The addition of interlocking screws affords additional control of alignment, length, and rotation for unstable fracture patterns. Finally, dynamization by interlocking screw removal may allow for enhanced rates of fracture union. One clinical problem with use of these devices in osteoporotic bone is distal locking screw backout or cutout with subsequent loss of fracture reduction.4,5 Most of the commercially available nails have a transverse, medial-to-lateral distal locking screw orientation; there are several new locking screw designs that are purported to provide better nail-screw stability. Although some authors suggest the use of one distal screw, two are recommended for osteoporotic bone.6–9 The purpose of the following studies was to examine the fixation stability of several types of these distal locking screws and alternative screw fixation configurations in osteoporotic femoral bone and simulated tibial fracture composite models. Twenty-four mildly osteoporotic femurs were selected based upon a bone density of 0.30 to 0.45 g/cm2 as determined by dual energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA). The distal femurs were osteotomized at 20 cm from the distal condyles and the distal 5 cm were fixed in metal holders using a low melting point alloy. They were distributed into four randomly selected groups of six femurs. For each group, supracondylar intramedullary nails (GSH, Smith & Nephew Richards, Memphis, TN) were inserted in a retrograde manner and locked with two distal, 5-mm screws using either standard cortical screws, step screws, standard screws with osteoporotic nuts and washers, or standard 5-mm screws inserted at a 30-degree crossing angle using a modified drill guide and nail (the screw holes in the nail were redrilled). These constructs are illustrated in Figure 31–1. The specimen holders were fixed in an angle vise at a 10-degree lateral tilt to create a slight varus bending moment when the nail was loaded. Testing was performed using an MTS machine (Model 810, MTS Corp., Minneapolis, MN). First the proximal end of the nail was axially loaded to 1000 N with a flat-faced applicator (the proximal nail end was not constrained) at a rate of 100 N/s, and resistance to motion of the nail was determined from the slope of the load displacement curve. The specimen was then radiographed to measure any screw movements. The specimen was remounted on the MTS and sinusoidally cycled to 105 cycles with a 500-N load, radiographed, and retested for axial stability. Unpaired t- tests between and paired within each test group were used to analyze the data. FIGURE 31–1 Types of distal fixation screws for femoral intramedullary nails. Left to right: step screws, osteoporotic nut and washers, standard screws, crossed screws. The resistance to motion for the four test groups before and after cycling is given in Table 31–1. The standard screw fixation became significantly more stable (P <0.01) after cycling; the other screw configurations developed less stability or remained unchanged. Precycling, the cross-screw configuration was significantly more stable than other methods of locking screw fixation (P <0.01). Postcycling, the cross-screw configuration had the same stability as the standard locking screws; both were significantly (P <0.05) more stable than the osteoporotic bolt and step screw. No gross inferior screw movements were detected radiographically, regardless of locking screw type or configuration; one of the standard distal locking screws backed out approximately 2 mm during cycling. There are two factors that could have affected the screw stability measurements: (1) the inherent screw rigidity, which is a function of the screw length, core diameter, and end fixation conditions,10,11

IMPROVING THE DISTAL FIXATION

OF INTRAMEDULLARY NAILS IN

OSTEOPOROTIC BONE

TESTING OF SCREW TYPES IN OSTEOPENIC FEMURS

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree