Chapter 2 Impingement Syndromes of the Foot and Ankle

General Technique Tips for Osteophyte Removal

Specific Anatomic Areas

The lesser metatarsophalangeal joints

Dorsal impingement in these joints usually is associated with Freiberg’s disease.1 This condition is no more common in athletes and dancers than it is in the general population. One should remember, however, that it can be symptomatic for as long as 6 months before it appears on x-ray and should be considered in unexplained metatarsalgia in young patients. A bone scan or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) usually will confirm the diagnosis before plain radiographic changes are evident. Freiberg’s infarction comes in the following four variations.1

Type I

The head of the metatarsal (MT) dies and then heals by “creeping substitution” (Phemister2). In this form it may heal completely, with little or no collapse, leaving the articular surface intact and almost as good as it was before the event occurred. Surgery often is not necessary.

Type IV

Multiple heads are involved in the process (Fig. 2-1). This type is rare and actually may be a form of epiphyseal dysplasia. Each MT head must be evaluated and treated individually.

A Freiberg-like syndrome can occur in the fifth MT head following a nondisplaced or minimally displaced fracture of the distal MT shaft, similar to the “boxer’s fracture” of the fifth metacarpal (Fig. 2-2).

Lesser MP joint instability

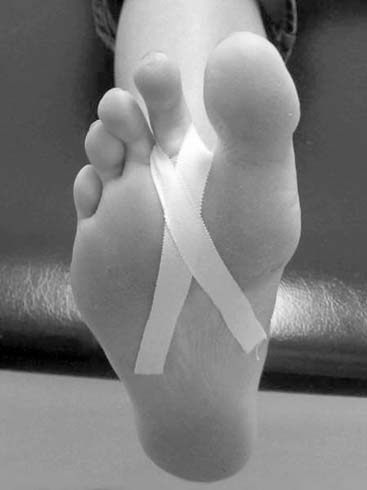

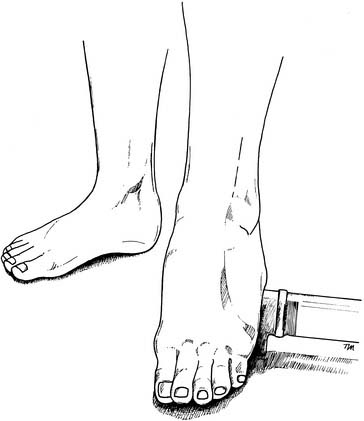

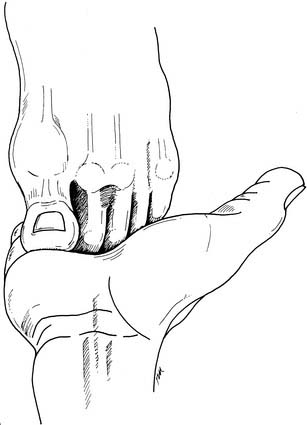

Metatarsalgia is not common in the young, healthy athletic population. When it is encountered, one should suspect either early Freiberg’s disease or MP instability.1 This subtle problem often goes unrecognized because the x-rays are normal. The patient presents with isolated metatarsalgia. There is plantar tenderness under the MT head and dorsal tenderness where the phalanx subluxes on top of the head when the patient relevés or goes up on the ball of the foot. The subluxated phalanx pushes the head of the metatarsal downward, producing the metatarsalgia, the so-called dropped metatarsal. It is recognized easily on physical examination if one remembers to observe for it. The Lachman test of the MP joint will be positive.1 The base of the proximal phalanx is grasped in the fingers, and a dorsal-plantar force is applied. The instability is recognized easily when the phalanx subluxes on the top of the MT head (Fig. 2-3).

Conservative treatment consists of padding to unload the painful MT head and taping or wearing a toe retainer to try to control the instability (Fig. 2-4). It often is a frustrating situation for the dancer or athlete because he or she does not want to undergo surgery, but once the ligaments and plantar plate are stretched, they can be tightened again only by surgery. The surgical options for this problem in a dancer are tricky. The usual operations for this condition (stabilizing procedures such as the Girdlestone-Taylor operation3) are inappropriate for athletes because they stabilize the joint but also limit dorsiflexion—an unacceptable solution for dancers, gymnasts, and so forth. We have had success in a limited number of dancers and athletes with a resection arthroplasty and partial syndactyly, especially in the fourth MP joint, which seems especially prone to this problem. As previously noted, one should not remove too much of the proximal phalanx (one-fourth to one-third at most), and one should remove the plantar condyles of the MT head, use a toe wire, and remove it early (2 weeks).

Idiopathic synovitis

Idiopathic synovitis4 is characterized by MP swelling, the so-called sausage toe. Its cause is controversial. (It usually is not caused by systemic inflammatory diseases, but of course these must be ruled out.) It usually is associated with laxity of the joint and MP instability. Whether the looseness irritates the joint and leads to chronic synovitis or the synovitis loosens the joint is not known. Conservative therapy involves stabilizing the joint by using tape or toe retainers (see Fig. 2-4); having the patient reduce activities and take anti-inflammatory medication; and, if necessary, giving the patient one or two (at most) intra-articular injections of steroids. If this fails, exploration and appropriate surgery are indicated. Surgical options include (1) extensor tendon lengthening with resection of the plantar condyles of the MT head, (2) Girdlestone-Taylor3 procedure, (3) DuVries-type arthroplasty,3 and (4) resection arthroplasty with partial syndactyly to the adjacent digit.

Medial midfoot impingements

An isolated osteophyte on the dorsum of the midfoot occasionally can cause entrapment of the deep peroneal nerve or irritation of the extensor hallucis longus (EHL) tendon as they pass over it. Initially, extra padding on the undersurface of the tongue of the shoe may resolve pain. If this fails, removal of the osteophyte may be necessary. The painful accessory navicular is not due to an impingement and is discussed in Chapters 8, 14, and 27.

Lateral midfoot impingements

Subluxation of the cuboid5 and derangement of the cuboid—base of the fourth and fifth metatarsal joints—often are seen together. The subluxing cuboid is a common but poorly recognized condition. It presents as lateral midfoot pain and an inability to “work through” the foot. Pressing on the plantar surface of the cuboid in a dorsal direction is painful. The normal dorsal-plantar joint play is reduced or absent when compared with the uninjured side. (Because of this immobility, the condition sometimes has been referred to as a “locked cuboid.”) Often there is a shallow depression on the dorsal surface, a palpable fullness on the plantar aspect of the cuboid, and subtle forefoot valgus. Documentation by x-ray, computed tomography (CT) scan or MRI is difficult because of the normal variations found in the relationship between the cuboid and its surrounding structures. The diagnosis must be made on the basis of the history and physical findings. Treatment involves recognition of the pathology and manual reduction by a therapist or physician familiar with the condition and follow-up to be certain that it remains in place. Therapists and orthopaedists involved in the care of athletes and dancers should be aware of the subluxed cuboid and be able to recognize it when it occurs. When the cuboid subluxes plantarward, the bases of the fourth and/or fifth metatarsals often are elevated, causing the head of the fourth metatarsal to be depressed (Fig. 2-5, Table 2-1).

Figure 2-5 A “dropped” fourth metatarsal head resulting from elevation of its base.

From Marshall PM, Hamilton WG: Am J Sports Med 20:170, 1992.

| Symptoms | Signs |

|---|---|

| Lateral midfoot pain | Tender plantar mass |

| Weakness in push-off | Decreased joint play |

| Inability to “work through” the foot | Shallow depression over the cuboid |

| Function limited by pain | Subtle forefoot abduction |

There usually are two types of cuboid subluxations: acute and chronic/recurrent. Treatment consists of recognition and manual reduction by a therapist familiar with the condition. The cuboid then must be held in place by taping and padding for several weeks to prevent recurrence. If the subluxation has gone unrecognized and the joint has been subluxed for any length of time, reduction can be difficult. The forefoot valgus must be corrected and the lateral column lengthened manually before the reduction can be performed. In the chronic condition, it may not be possible to keep the cuboid reduced if it goes in and out at random. In these cases, athletes often can be taught to reduce the subluxation themselves (Fig. 2-6).

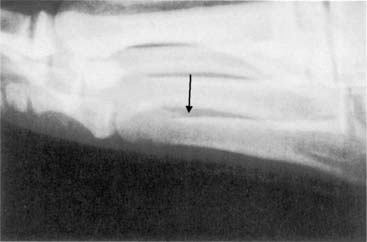

Sinus tarsi syndrome4 is a controversial condition that produces pain deep in the sinus tarsi that increases with activity and is exacerbated by impact (jumping and running) and pronation. It is often, but not always, a sequel to a sprained ankle. On physical examination, there is discrete tenderness, or a “trigger point” deep in the sinus tarsi, and forceful abduction-pronation of the heel and midfoot may be painful. The condition usually can be confirmed with an injection of 0.5 ml of lidocaine into the trigger point. If the pain is relieved by the local anesthetic, a second injection of 0.15 ml of corticosteroids often can be highly effective. The condition is thought to have several etiologies: (1) soft tissue entrapment or partial tear of the interosseous talocalcaneal ligament, (2) osteophyte impingement (Fig. 2-7), (3) neural entrapment (motor nerve to the extensor digitorum brevis [EDB]), (4) degenerative arthrosis, and (5) arthrofibrosis. It can be difficult to differentiate this syndrome from subtalar dysfunction, and osteophytes can be found in the sinus tarsi that are not causing symptoms. The two areas are anatomically close together. One of the best ways to differentiate one from the other is to pay close attention to subtalar motion. Mann and Coughlin3 have shown how important subtalar motion is to normal foot mechanics. Subtle loss of this motion, such as arthrofibrosis of the subtalar joint from bleeding into the joint in conjunction with an ankle sprain, can cause residual symptoms after the sprain has healed.

Conservative treatment consists of anti-inflammatory medication, physical therapy, a medial heel wedge or arch support to open up the sinus tarsi, and, if necessary, the previously mentioned cortisone injection. If symptoms persist and the diagnosis has been confirmed with lidocaine injection, surgical exploration and clean-out is indicated. This is one area in which an injection—if placed in the right spot—often is dramatically effective and will avoid surgery. Finally, the sinus tarsi syndrome often is found in conjunction with lateral ankle ligament laxity, and, in these cases, sinus tarsi exploration and debridement should be considered if ankle ligament reconstruction is planned. More about the subtalar joint can be found in Chapter 15.

The ankle

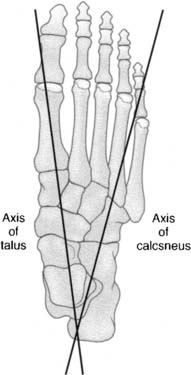

When considering ankle impingement, one should remember the basic anatomy of the ankle. The talus sits sidesaddle on the os calcis so that the axis of the talus is roughly in line with the first web space of the foot and the axis of the os calcis is in line with the fourth web space (Fig. 2-8). In dorsiflexion, bony impingement occurs anteromedially between the neck of the talus and the anterior lip of the tibia. In plantarflexion, bony impingement occurs posterolaterally between the os calcis and the posterior lip of the tibia. Therefore anteromedial and posterolateral problems usually are associated with bony impingement, whereas anterolateral and posteromedial problems usually are soft tissue in origin (there is no bony impingement in these areas). The anterior ankle is an extremely common location for impingement, but impingements can be found in all quadrants around the ankle: anterior, lateral, posterior, and medial.

Anterior (medial, central, lateral)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree