Abstract

Rehabilitation care and physical exercise are known to constitute an effective treatment for chronic peripheral arterial occlusive disease (PAOD) at the intermittent claudication (IC) stage. Improvements in functional capacities and quality of life have been reported in the literature. We decided to assess the effects of hospital-based exercise training on muscle strength and endurance for the ankle plantar and dorsal flexors in this pathology.

Patients and methods

This prospective study included 31 subjects with chronic peripheral arterial occlusive disease (PAOD) and IC who followed a 4-week rehabilitation program featuring walking sessions, selective muscle strengthening, general physical exercise and therapeutic patient education. An isokinetic assessment of ankle plantar and dorsal flexors strength was conducted on the first and last days of the program. We also studied the concentric contractions at the angular velocity of 30°/s and 120°/s for muscle strength and at 180°/s for muscle fatigue. We also measured the walking distance for each patient.

Results

Walking distance improved by 246%. At baseline, the isokinetic assessment revealed severe muscle weakness (mainly of the plantar flexors). The only isokinetic parameter that improved during the rehabilitation program was the peak torque for plantar flexors at 120°/s.

Conclusion

All patients presented with severe weakness and fatigability of the ankle plantar and dorsal flexors. Our program dramatically improved walking distance but not muscle strength and endurance.

Résumé

Introduction

La rééducation et l’exercice physique sont reconnus comme des traitements efficaces de l’artériopathie oblitérante des membres inférieurs au stade de la claudication intermittente (CI), avec en particulier une amélioration des capacités fonctionnelles et de la qualité de vie. Nous présentons ici l’effet de programme de reconditionnement en milieu hospitalier sur la force et l’endurance des fléchisseurs plantaires et dorsaux dans cette affection.

Patients et méthode

Dans le cadre d’une étude prospective, 31 patients présentant une artériopathie avec CI ont été inclus dans un programme de quatre semaines incluant des séances de marche, du renforcement segmentaire, de l’activité physique globale et une éducation du patient. Une évaluation isocinétique de la force des fléchisseurs plantaires et dorsaux des chevilles a été réalisée les premier et dernier jours du programme. Nous avons étudié la force de contraction concentrique à 30 et 120° par seconde et la fatigue musculaire à 180° par seconde. Nous avons également mesuré le périmètre de marche.

Résultats

Le périmètre de marche s’est allongé de 246 %. À l’admission, l’évaluation isocinétique montrait une faiblesse sévère prédominant sur les fléchisseurs plantaires. Le seul paramètre isocinétique qui s’est amélioré à l’issue du programme était le moment maximal des fléchisseurs plantaires à 120° par seconde.

Conclusion

Les patients artéritiques présentaient tous une faiblesse et une fatiguabilité importante des fléchisseurs dorsaux et plantaires des chevilles. Notre programme s’est montré très efficace pour améliorer le périmètre de marche, mais pas pour augmenter la force et l’endurance musculaires distales des membres inférieurs.

1

English version

1.1

Introduction

The relevance of rehabilitation programs in the therapeutic care of peripheral arterial occlusive disease (PAOD) has been validated. The recommendations from the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association as well as their French counterparts showed that at the intermittent claudication stage the primary treatment is based on rehabilitation training programs. The recommendations from the Trans-Atlantic Inter-Society Consensus (TASC) working-group in 2000 underlined the essential and mandatory nature of physical exercise for all patients with PAOD . Simple exercise recommendations are often quite insufficient. Supervised walking training programs have more positive impact than plain advice on walking. Patterson et al. showed that a hospital-based program was more effective than home-based programs . The most tangible impact of PAOD rehabilitation is the great improvement of the walking distance, in average 150% . The Cochrane meta-analysis from Watson et al. reported a significant improvement of the walking distance associated to an increase in walking time after physical training sessions. Perkins et al. compared rehabilitation training to angioplasty treatment and showed that exercise training was more effective than angioplasty for improving the walking distance after 15 months of treatment . Increasing walking distance with rehabilitation training brings significant qualitative and quantitative improvement in completing daily life tasks. For the first time, Garg et al. showed that patients with PAOD who were more active in their daily life routine had a significantly lower mortality rate and associated cardiovascular complications than persons with little physical activity . The effectiveness of rehabilitation on PAOD is probably linked to better muscle perfusion and the development of better activity of aerobic enzymes in skeletal muscle fibers avoiding the onset of lactic acid build-up . In 2004, Demonty et al. highlighted, through isokinetic assessment, a decrease in muscle strength and increased muscle fatigue on the ankle plantar and dorsal flexors in patients with PAOD . In order to evaluate the effect of a rehabilitation-training program on muscle strength and endurance of the lower limbs in patients with peripheral arterial occlusive disease, we conducted an open and prospective study.

1.2

Patients and method

Not-controlled prospective study.

1.2.1

Population studied

All patients included in the PAOD rehabilitation program between June 2005 and June 2008, were recruited for the study.

The patients were included after a medical consultation with an angiology or cardiology specialist. The following clinical elements were collected:

- •

results of the arterial Doppler ultrasound of the lower limbs in order to establish a mapping of the arterial disease lesions;

- •

walking distance and ankle-brachial systolic pressure index (ABPI) at rest and during effort, on a treadmill according to a standardized protocol (slope 10%; speed 3.2 km/h);

- •

screening for exercise-induced myocardial ischemia or arrhythmia, by performing a dobutamine stress echocardiogram possibly associated to myocardial perfusion imaging by PET/CT-scan and/or coronarography.

The clinical check-up and additional examinations did allow for verifying the inclusion and exclusion criteria for the rehabilitation program.

Inclusion criteria:

- •

Stage II Peripheral Arterial Occlusive Disease; Intermittent Claudication Fontaine Stage II PAOD (with a walking distance on the treadmill < 400 m) or Fontaine Stage III,

- •

PAOD after endovascular and/or surgical revascularization (> 1 month);

Exclusion criteria:

- •

uncertain of patient’s cardiac status (check-up older than 6 months or not done);

- •

severe or unstable cardiopulmonary pathologies, contra-indications to effort strength training, especially aortic dissection and atheromatous emboli or stenosis at the prethrombotic state without potential collateral consequences (following the recommendations from the French Cardiology Society );

- •

critical lower limb ischemia (Stage IV PADO);

- •

acute lower limb ischemia;

- •

recent thromboembolic disease (< 6 months);

- •

progressive infectious or inflammatory disease;

- •

severe diabetes-related complications: neuropathy, diabetic foot, proliferative retinopathy preventing the completion of a rehabilitation program.

- •

any orthopedic problem ruling out exercise training;

- •

recent laparotomy < 3 months (especially in case of aortoiliac bypass);

- •

patient not wanting to be part of the rehabilitation program.

At the end of this consultation, the patient was informed about the rehabilitation program and signed a written consent.

1.2.2

Rehabilitation protocol

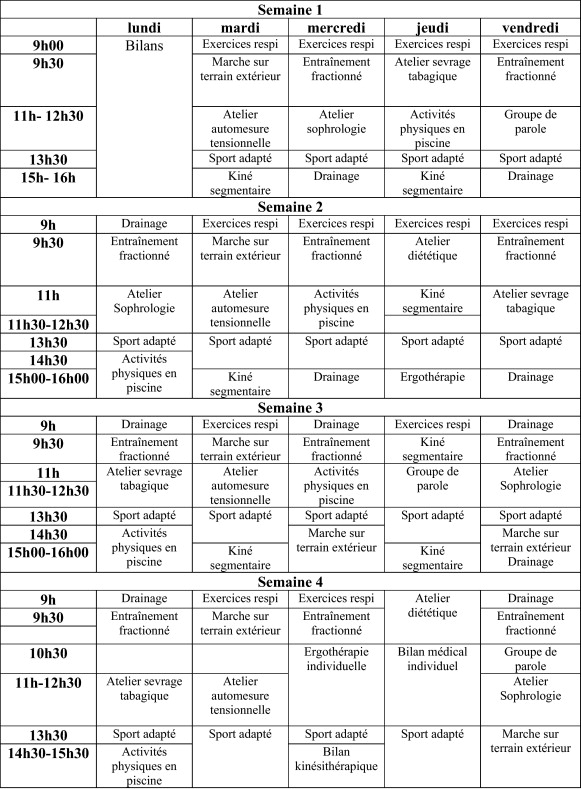

This rehabilitation program took place at the day hospital, 5 days a week during four consecutive weeks ( Fig. 1 ).

The first day of the program was dedicated to check-up (clinical examinations, Baecke physical activity questionnaire and evaluation parameters described below).

Each day was dedicated to training, individually or in group sessions, associated to various activities organized around the two main facets of the program: rehabilitation and education.

The program included:

- •

physiotherapy;

- •

respiratory physiotherapy (clearing secretions if necessary);

- •

fractioned walking exercises on the treadmill and outside;

- •

selective muscle strengthening: repetitive dynamic contractions over a short period of time on the muscle groups closest to the stenosis (proximal lesion: sit to stand transfers facing the wall bars; medium lesion: standing up on tiptoe while facing the wall bars; distal lesion: flexing the toes);

- •

manual lymphatic drainage or venous drainage depending on the cases;

- •

occupational therapy with thorough evaluation and practical solutions proposed to facilitate daily activities;

- •

physical activities and sports;

- •

therapeutic patient education;

- •

self-assessment of blood pressure;

- •

diet and nutritional advice;

- •

effect of cigarette smoking;

- •

discussion support groups;

- •

an interview with a physician was systematically planned at the end of each week.

In the framework described above, the program was personalized for each patient. The patients were required to wear a heart rate monitor during exercises; the maximal tolerated heart rate was set at 70% of the HR max .

1.2.3

Initial and final evaluations

They included:

- •

an assessment of the walking distance on a flat surface and on a pre-established course, at a comfortable speed for the patient (in meters), up to the onset of pain forcing the patient to stop, according to the recommendations from the French National Health Agency (HAS) ;

- •

a selective muscle training evaluation with 28 contractions per minute and expressed in the number of contractions up to the onset of pain according to the recommendations from the French National Health Agency (HAS) ;

- •

an isokinetic evaluation of muscle strength and endurance.

1.2.4

Isokinetic evaluation

The evaluation of muscle strength and fatigue focused on the triceps surae and ankle dorsal flexors using a Cybex 6000 ® dynamometer on the first and last days of the program.

The evaluation of the isokinetic ankle plantar and dorsal flexors strength was measured with an angle at 15° in dorsal flexion – 0°–25° in plantar flexion.

First, patients did a 10-minute warm-up session on a bike (40 W, 40 pedal rounds per minute). Then would get familiar with the dynamometer during a warm-up session (three repetitions of the movement at a set speed).

Each test was conducted at the same hour of the day by the same operator according to the recommendations of the French National Health Agency (HAS) , before any physical activity, without any cigarette smoking or caffeine intake in the hour before the test.

To evaluate muscle strength, the subject did three series of five movements at the angular velocity of 120°/s and three movements at 30°/s, on the left and right side, in concentric mode.

There was a 30-second rest period between each series.

The fatigue test included 20 repetitions at 180°/s .

The heart rate was checked at the end of each series.

The isokinetic parameters kept were:

- •

for muscle strength:

- ∘

peak torque per body mass at 30 and 120°/s, for the right and left ankle plantar and dorsal flexors (expressed in %),

- ∘

peak torque ratio dorsiflexors/plantar flexors;

- ∘

- •

for muscle fatigue:

- ∘

total work at 180°/s, per body mass for the right and left ankle plantar and dorsal flexors (expressed in %);

- ∘

1.2.5

Statistical analysis

Mean values and standard deviations were calculated for the entire set of data. To analyze the differences between the performances at baseline and upon completing the program (numerical items), a paired Student- t test was used when the sample size was ≥ 30; a paired Wilcoxon test was done when the sample size was < 30. For qualitative parameters (reaching the 50% fatigue threshold or not), a McNemar test was used. A correlation analysis was done between clinical and isokinetic parameters using the Pearson’s correlation coefficient if the sample size was ≥ 30 or the Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient the sample size was < 30. Values were deemed significant when p < 0.05.

1.3

Results

Thirty-eight patients benefited from this PAOD rehabilitation program at the Swynghedauw hospital within the CHRU of Lille, between June 2005 and June 2008.

Seven patients were excluded from the protocol for medical reasons:

- •

one patient was excluded at baseline for acute lower limb ischemia;

- •

two patients were excluded two weeks into the program, one for malignant hypertension, the other one for decompensated chronic obstructive pulmonary disease;

- •

one patient had to stop the program during one week due to a poorly adjusted pacemaker (implanted for infrahissian conduction impairment);

- •

three other patients did not benefit from isokinetic evaluations; the dynamometer was under maintenance during their sessions.

The data from 31 patients were used for the statistical analysis.

Our sample included 96.7% of men and 3.3% of women. The mean age of patients was 55.7 ± 10.5 years (mean ± standard deviations). Most patients (97.7%) had an additional risk factor 53.3% were active smokers and 43.4% former smokers, smoking was evaluated in average at 40 ± 22.7 pack year.

Only 3.3% of patients had never smoked.

The etiology of the PAOD was atheroma in 28 cases, one case of antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) and one case of thrombophilia. In one patient the etiology remained undetermined.

Bilateral walking pain was present in 54.8% of the cases, unilateral in 45.2% of the cases with an equal distribution between the right and left side (22.6% on the right side, 22.6% on the left side).

The location of the stenosis was proximal in 32.3% of the cases (aorta, iliac, common femoral), femoropopliteal or more distal in 32.3% of the cases and diffuse in 35.4% of the cases.

Among the patients, 35.5% had no history of vascular intervention and 64.5% had a prior therapeutic intervention (25.8% had an angioplasty, 16.1% had a coronary bypass and 22.6% had a combination of both angioplasty + bypass).

Most patients were at Stage II PAOD (87.1%), and 12.9% at Stage III. The Baecke questionnaire on physical activity found a physical activity at work (PAW) index at 3.13 ± 0.69 for patients who were working, a sport during leisure time (SLT) index at 1.76 ± 0.78 and a physical activity during leisure time excluding sport (LT) index at 2.85 ± 0.59. The walking distance evaluated at baseline, with slope at 10% and speed at 3.2 km/h, was quite weak with a mean at 230.7 ± 221 meters.

1.3.1

Evolution of the clinical parameters between the initial and final evaluations

These results are presented in Table 1 . The walking distance went from a mean 282.4 (standard deviation: 239.8) at baseline to 977 meters (± 854.2) upon completing the program, thus a 246% improvement highly significant on a statistical level ( p < 0.0001).

| Before | After | Progression (%) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Walking distance (in meters) | 282.4 ± 239.8 | 977.4 ± 854.2 | + 246 | < 0.0001 |

| Reference for selective muscle work ( n of repetitions) | 32 ± 17.8 | 57.1 ± 32.6 | + 78.4 | < 0.0001 |

Regarding selective muscle training, the values went from 32 contractions at baseline (±17.8) to 57.1 (±32.6) at the end of the program, i.e. significant improvement of 78.4% ( p < 0.0001).

1.3.2

Evolution of the isokinetic parameters between the initial and final consultations

1.3.2.1

Muscle strength

The results are presented in Table 2 .

| Parameters (°/s) | Muscles | Initial evaluation (N/m) | Final evaluation (N/m) | Progression (%) | Significance ( p ) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PT 30 | RDF | 26 ± 14.11 | 26 ± 14.9 | + 0 | 0.66 |

| LDF | 25.7 ± 14.9 | 26.1 ± 12.9 | + 1.5 | 0.25 | |

| RPF | 67.3 ± 28.6 | 72.1 ± 28.4 | + 7.1 | 0.0424 | |

| LPF | 68.7 ± 25 | 73.6 ± 27.8 | + 7.1 | 0.12 | |

| PT 120 | RDF | 21.1 ± 11.7 | 20.7 ± 12 | − 1.9 | 0.74 |

| LPF | 18.9 ± 12.8 | 19.9 ± 11.8 | + 5.3 | 0.26 | |

| RPF | 42.3 ± 19 | 48 ± 20.9 | + 13.5 | 0.0009 | |

| LPF | 43.2 ± 16.6 | 48 ± 18.3 | + 11.1 | 0.0019 |

No significant improvement was noted for peak torque of dorsal flexors on the left or right side, at 30°/s, or at 120°/s.

For plantar flexors, peak torque at 30°/s significantly improved between baseline and the end of the program, on the right side (peak torque per body mass) went from 67.3 ± 28.6% to 72.1 ± 28.4, i.e. a 7.1% improvement. This improvement was not found on the left side.

At 120°/s, the peak torque for the left and right plantar flexors improved considerably between baseline and the final evaluation: it went from 42.3 ± 19 and 43.2 ± 16.6 respectively, to 48 ± 20.9 and 48 ± 18.3, showing an improvement of 13.5 and 11.1%.

1.3.2.2

Peak torque ratio of plantar flexion to dorsiflexion (PF/DF)

The results are listed in Table 3 .

| Speed (°/s) | Side | Initial evaluation (%) | Final evaluation (%) | Progression (%) | Significance ( p ) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30 | Right | 56.3 ± 65.1 | 46.7 ± 38.3 | − 17 | 0.19 |

| Left | 48.6 ± 53.7 | 40.5 ± 24.7 | − 16.7 | 0.99 | |

| 120 | Right | 71.9 ± 72.7 | 62.1 ± 57.6 | − 13.6 | 0.15 |

| Left | 55.3 ± 68.8 | 48.9 ± 39 | − 11.6 | 0.43 | |

| 180 | Right | 68 ± 78.9 | 125 ± 237.9 | + 85.1 | 0.26 |

| Left | 56.9 ± 66.6 | 99.8 ± 149.3 | + 75.4 | 0.53 |

No significant change was noted for peak torque ratio between the initial and final evaluations. Peak torque ratio PF/DF at 180°/s could only be measured for 22 patients out of 31 because in nine patients PF peak torque was null.

1.3.2.3

Muscle fatigue

Results are presented in Table 4 .

| Parameters | Muscles | Initial evaluation | Final evaluation | Progression (%) | Significance ( p ) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TW 180°/s | RDF | 2.5 ± 4.6 | 5 ± 7.7 | + 100 | 0.065 |

| LDF | 3.3 ± 5.7 | 5 ± 6.8 | + 51.5 | 0.081 | |

| RPF | 11.7 ± 13.5 | 14.1 ± 12.9 | + 20.5 | 0.049 | |

| LDF | 10.9 ± 11.7 | 12.5 ± 10.8 | + 14.7 | 0.102 |

Nine patients could not complete the fatigue test at baseline, and among these patients, two subjects were still unable to complete the test after the 4-week training program. Faced with a high number of patients unable to complete the 20 successive repetitions for the fatigue test, we analyzed time to fatigue at 50% of maximal voluntary isometric contraction (MVC), i.e. the number of movements above which the muscle lost 50% of its initial strength. We did not find any significant difference between the initial and final evaluations regarding time to fatigue at 50% MVC. In average time to fatigue at 50% MVC occurred after six to nine movements for ankle dorsal flexors and 10 to 12 movements for plantar flexors. Very few patients had not reached that threshold after 20 movements: 3 to 16% for dorsal flexors and 20 to 25% for plantar flexors, with no significant difference between baseline and the end of the program.

1.3.2.4

Total work at 180°/s

For dorsal flexors no significant improvement of the total work per body mass at 180°/s was reported between the initial and final evaluations.

For plantar flexors there was only a significant improvement on the right side (total work went from 11.7 ± 13.5 to 14.1 ± 12.9, amounting to a 20.5% improvement).

1.3.3

Correlations

No correlation was found between the improvement of clinical parameters and the improvement of isokinetic parameters.

1.4

Discussion

In peripheral arterial occlusive disease of the lower limbs, muscle strength and endurance are weaker due to decreased arterial blood flow associated to a reduction in muscles’ aerobic capacity . The initial evaluation did show major muscle weakness and fatigue for the ankle dorsal and plantar flexors. After the 4-week rehabilitation program, clinical parameters, i.e. walking distance and number of repetitions during selective muscle training, had greatly improved. However, there was no significant improvement of the isokinetic parameters. Even though the recommendations of the French and American cardiology society suggest that for PAOD at the IC stage, primary treatment should be rehabilitation care, our population was at a more advanced stage of the disease. Almost two-thirds of our patients had a history of previous complications with numerous and complex treatments (e.g., thrombosed coronary bypass, angioplasty failure). The health status of our population was quite uncertain, explaining the three complications and exits from the study. In fact, two patients died the year following this rehabilitation program, validating the increased cardiovascular mortality rate for PAOD at the IC stage .

The physical activity of our patients, evaluated with the Baecke self-questionnaire, was quite low with a mean sport index (SLT) at 1.76 ± 0.78 and a mean physical leisure activity (LT) index at 2.85 ± 0.59.

In the literature, few studies on populations with peripheral artery disease (PAD), evaluated muscle force and fatigue for ankle dorsal and plantar flexors using isokinetic dynamometers. Studies comparing subjects with PAD to healthy subjects reported a significant decrease in muscle force and increased muscle fatigue for the triceps surae , dorsiflexors , ankle dorsal and plantar flexors in patients with PAD. We used the same protocol previously reported by Demonty et al. . The values for peak torque of total work in our population were greatly below the ones reported by Demonty et al. In fact dorsiflexors peak torque values at the angular velocity of 30°/s were respectively 3.5 on the right side and 3.6 on the left side Nm/kg, in the study by Demonty et al., whereas they were at 0.26 Nm/kg in our study a value 13 to 14 times lower. At 120°/s, our patients were eight times weaker and at 180°/s they were a hundred times weaker. For plantar flexors, our patients were 13 times weaker than their patients at 30°/s, seven to eight times weaker at 120°/s and 77 to 86 times weaker at 180°/s. Even though it is quite difficult to compare isokinetic data collected by two different teams with two different dynamometers, the gap in values between the two studies did validate the severity of PAOD in our patients.

In our study, peak torque ratios of plantar flexion to dorsiflexion (PF/DF) were comprised between 49 and 72% at baseline and between 40 and 125% at the end of the rehabilitation program. Very few studies are available on isokinetic standards for the ankle. Calmels et al. in healthy subjects, found peak torque ratios of PF/DF comprised between 41 and 68% in concentric mode, with an increased ratio at angular velocity. The angular velocity tests were different from ours (60, 120 and 240°/s).

Peak torque ratios of PF/DF were rather high in our study and point to a predominant impairment on the ankle plantar flexors. In 1986, Gerdle et al. reported a significant decrease in muscle strength and increased muscle fatigue for the triceps surae in patients with PAD compared to healthy subjects. On the other hand, in an isokinetic setting, Scott-Okafor et al., compared the strength of lower limbs (hips, knee and ankle) in older patients with PAD vs. healthy subjects , they highlighted a clear weakness of the ankle dorsal flexors in patients with PAD vs. healthy subjects, and within the population with PAD dorsal flexors’ weakness was predominant on the limb most affected by PAD. No significant difference was reported for other muscle groups. In the study by Demonty et al. , dorsal and plantar flexors were affected in the same proportions since peak torque ratios were identical in the population with PAD and the control group, i.e. between 30 and 40% at 30 and 120°/s.

Our rehabilitation program was more intense and shorter than the set recommendations (at least 30 minutes, three times a week for 3 months). It did however yield the expected positive effects on the studied clinical parameters, matching the data from the literature . According to a meta-analysis conducted by the French National Health Agency (HAS) , the mean increase in walking distance was 150%, with a minimum at 74% and maximum at 230%. For our patients, the walking distance improved by 246%, at the end of the program the distance was close to one kilometre. This significant increase, well beyond the usual data found in the literature, was probably due to the high intensity of our rehabilitation protocol. The number of successive repetitions during selective muscle training did also improve by 78.4%, between the initial evaluation and the final one.

This clear functional improvement contrasts with the weak increase in muscle force or resistance to fatigue for ankle muscles in isokinetic training, regardless of angular velocity. We did not find a correlation between the improvement in clinical parameters and the increased peak torque of plantar flexors. The improvement in muscle strength at 30°/s and muscle endurance for plantar flexors on the right side must be interpreted with caution ( p = 0.0424 and 0.049, respectively).

However, the bilateral strength improvement for the plantar flexors at 120°/s is significant ( p = 0.0009 on the right side and p = 0.0019 on the left side).

Very few studies have focused on the evolution of muscle strength and fatigue during PAOD rehabilitation training. The patient positioning and test settings condition the results and probably the metrological quality of the isokinetic test. Because of the great disparity in isokinetic evaluation of ankle muscles and the scarcity of precise data related to their reproducibility we were not able to find standards for the various parameters studied. Hebderg et al. compared strength and fatigue of the plantar flexors in patients with PAD, after coronary bypass vs. rehabilitation training . The walking distance improved in both groups but the improvement in isokinetic performances was higher in the group of patients who had bypass surgery than in the rehabilitation group. The exercise program consisted only in repeated standing on tiptoe movements at home. Our small number of patients did not allow for comparing the effects of our rehabilitation program on patients after angioplasty, surgery or medical treatment alone.

The fatigue test did not unveil any significant improvement between the initial evaluation and the final one, expect for the total work of the right plantar flexors. This test consisted in doing 20 successive movements of dorsiflexion/plantar flexion of the ankle at the angular velocity of 180°/s. Almost 30% of patients were not able to complete the fatigue test at the initial evaluation and about 10% of them could still not complete the test at the final evaluation. The number of repetitions, 20 for an angular velocity set at 180°/s, seems quite low compared to Gerdle et al. , whose patients with PAD could complete 200 repetitions at 60°/s. However, in their study, most patients had given up after 40 repetitions. We did not show any significant difference regarding time to fatigue at 50% of maximal voluntary isometric contraction (MVC). The main drawback of this parameter is the risk of error related to improper subject’s performance during this test . In fact, sometimes on one or two movements, there is an abnormal decrease in strength followed by higher strength in the following movements. This abnormal decrease in strength can correspond to values below 50% of the initial strength and thus alter final test results. The evaluation of muscle strength and muscle fatigue in our study was done in concentric contraction mode. However, when walking, muscles at ankle level are more solicited on an eccentric mode. Since patients’ walking abilities significantly improved, evaluating muscle strength and fatigue on an eccentric mode could have validated significant changes between the initial evaluation and the final one.

Regardless, our protocol was designed to improve the walking distance. The metabolic responses involved in isokinetic evaluation, including the so-called fatigue test are different from the ones used during walking. It is then quite logical for our results to be better on walking. We could have expected a better convergence of the results between the improvement of selective muscle training and the isokinetic fatigue tests. The intensity of muscle solicitation on an isokinetic dynamometer was quite difficult for most patients, at the initial evaluation and at the end of the program.

1.5

Conclusion

The isokinetic evaluation in concentric mode allowed for measuring the importance of muscle weakness and fatigue in patients with PAOD. Weakness and fatigue affected proportionally more the ankle plantar flexors than dorsal flexors. It would be relevant to study these same parameters in eccentric mode, as this type of contraction is important when walking. Our study validated the positive effects of an intensive rehabilitation program on the walking distance and the number of repetitions in selective muscle training. However, we could only report modest isokinetic performances for muscle strength and endurance.

It is quite logical to bring up the relevance of associating specific muscle strengthening exercises for leg muscles to a rehabilitation program designed for patients with PAOD.

Disclosure interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest concerning this article.

2

Version française

2.1

Introduction

L’intérêt des programmes de Rééducation dans la prise en charge de l’artériopathie oblitérante des membres inférieurs (AOMI) fait l’objet d’un consensus professionnel. Les recommandations américaines, de l’American College of Cardiology et de l’American Heart Association et françaises indiquent qu’au stade de claudication, la prise en charge de première intention repose sur la mise en place de mesures de rééducation. Les recommandations du Trans-Atlantic Inter-Society Consensus (TASC) Working Group en 2000 comprenaient l’indication permanente et indispensable de l’activité physique dans cette pathologie . Les simples conseils de pratique d’exercice physique donnés aux patients s’avèrent souvent très insuffisants. Les programmes d’entraînement à la marche supervisés sont plus efficaces que de simples conseils de marche. Patterson et al. ont montré qu’un programme hospitalier était plus efficace qu’un programme à domicile . L’impact le plus tangible de la réadaptation de l’AOMI est l’augmentation importante de la distance de marche, en moyenne de 150 % . La méta-analyse Cochrane de Watson et al. concluent en une amélioration significative du périmètre et de la durée maximale de marche après entraînement physique. Perkins et al., comparant la rééducation à l’angioplastie, montraient que l’exercice était plus efficace que l’angioplastie sur l’amélioration de la distance de marche au bout de 15 mois de traitement . L’augmentation de la distance de marche avec la rééducation aboutit à une amélioration quantitative et qualitative de la réalisation des activités quotidiennes. Garg et al. ont montré pour la première fois que les patients porteurs d’AOMI les plus actifs dans la vie quotidienne présentaient une mortalité et une morbidité cardiovasculaire significativement plus faibles que les sujets peu actifs .

L’efficacité de l’entraînement dans l’AOMI est vraisemblablement liée à la meilleure perfusion musculaire et au développement de l’équipement enzymatique aérobie des fibres musculaires évitant la survenue d’une acidose lactique .

En 2004, Demonty et al. ont mis en évidence, par évaluation isocinétique, une diminution de la force et une augmentation de la fatigabilité musculaire, au niveau des fléchisseurs plantaires et dorsaux de la cheville, chez les patients porteurs d’AOMI . Afin d’évaluer l’effet d’un programme de réentraînement sur la force et l’endurance musculaires distales des membres inférieurs chez des patients souffrant d’artériopathie oblitérante des membres inférieurs, nous avons réalisé une étude ouverte, prospective.

2.2

Patients et méthode

Étude prospective non contrôlée.

2.2.1

Population concernée

Ont été recrutés, tous les patients inclus dans le programme de rééducation de l’AOMI entre juin 2005 et juin 2008.

Les patients ont été inclus à la suite d’une consultation médicale, par les médecins angiologues ou cardiologues. Les éléments para-cliniques suivants étaient vérifiés :

- •

les résultats de l’échographie doppler artérielle des membres inférieurs, afin d’établir une topographie des lésions d’artériopathie ;

- •

la distance de marche et index de pression systolique de cheville au repos et à l’effort, sur tapis roulant selon un protocole standardisé (pente 10 % ; vitesse 3,2 km par heure) ;

- •

le dépistage d’une ischémie myocardique d’effort, ou de troubles du rythme, par échographie de stress à la dobutamine plus ou moins complété par une scintigraphie myocardique et/ou une coronarographie.

Le bilan clinique et para-clinique permettait de vérifier les critères d’inclusion et d’exclusion du programme de rééducation.

Critères d’inclusion :

- •

une AOMI aux stades II (avec une distance de marche sur tapis roulant inférieure à 400 m) ou III de la classification de Leriche et Fontaine ;

- •

une AOMI après revascularisation endovasculaire et/ou chirurgicale (plus d’un mois).

Critères d’exclusion :

- •

un statut cardiaque incertain (bilan supérieur à six mois ou non réalisé) ;

- •

des pathologies cardiopulmonaires sévères ou instables, contre-indiquant le réentraînement à l’effort, notamment dissection aortique et lésion athéromateuse emboligène ou sténose préthrombotique sans collatéralité potentielle (suivant les recommandations de la Société française de dardiologie ) ;

- •

une ischémie critique des membres inférieurs (AOMI au stade IV) ;

- •

une ischémie aiguë du membre inférieur ;

- •

une maladie thromboembolique récente (inférieure à six mois) ;

- •

une maladie infectieuse ou inflammatoire évolutive ;

- •

des complications sévères du diabète : neuropathie, pied diabétique, rétinopathie proliférative ne permettant pas la réalisation du programme de rééducation ;

- •

tout problème orthopédique interdisant la pratique de l’exercice ;

- •

une laparotomie récente datant de moins de trois mois (notamment en cas de pontage aorto-iliaque) ;

- •

patient ne souhaitant pas adhérer au programme.

À la fin de cette consultation, le patient était informé sur le programme de rééducation et signait un consentement écrit.

2.2.2

Protocole de rééducation

La prise en charge s’est effectuée en hospitalisation de jour, cinq jours par semaine pendant quatre semaines consécutives ( Fig. 1 ).