Abstract

Objective

To evaluate simple, measurable indicators of optimal organizational procedures for the hospital-to-home discharge of dependent patients.

Material and method

All the general practitioners (GPs) in the Maine-et-Loire county of France were sent a questionnaire asking them to rank the three main criteria (from the most important to the least significant) from a list of 14. We analyzed the median ranking for each item and identified the most important items in terms of their relative frequency.

Results

The response rate was 10.77% (104 out of 966). Four criteria had a median score over 9: contact with the GP prior to discharge, informing the GP of the discharge date, training for the patient and his/her family in activities of daily living and providing a list of people to be contacted in the event of a problem at home. Respite hospitalization (in the event of difficulties at home) was cited as one of the three most relevant criteria.

Discussion-Conclusion

The criteria highlighted by the GPs were not highly specific for the discharge of a dependent patient. However, it would be interesting to extend this study by interviewing other stakeholders and determining whether these criteria indeed improve the organization of hospital-to-home discharge.

Résumé

Objectifs

Recueillir l’avis des médecins généralistes (MG) concernant les critères de bonne organisation de la sortie d’un service de MPR d’un patient dépendant.

Matériel et méthode

Les MG du Maine-et-Loire ont été interrogé, via un questionnaire, afin d’évaluer 14 critères prédéfinis à partir des recommandations existantes et d’en classer trois par ordre décroissant de leur importance. Les critères les plus pertinents ont été dégagés via l’analyse des médianes pour chaque item et des fréquences de distribution relative.

Résultats

Cent quatre MG ont répondu sur 966 sollicités. Quatre critères (contact avec le MG par le service, connaissance de la date de sortie, formation du patient et de sa famille aux gestes de la vie courante, listes des contacts possibles) ont une médiane supérieure à 9. La proposition de répit en cas de difficultés à domicile est citée parmi les trois critères les plus pertinents.

Discussion-Conclusion

Les critères retenus traduisent d’abord les besoins non spécifiques de coordination ville–hôpital. Certains, plus particuliers au retour d’une personne dépendante, s’inscrivent dans le contexte du développement de programme d’éducation thérapeutique. Il faudra interroger ultérieurement les autres acteurs du retour à domicile et évaluer l’efficience de ces critères sur organisation de celui-ci.

1

English version

1.1

Introduction

The hospital-to-home discharge of a caregiver-dependent patient after hospitalization in a Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine (PRM) service is an essential step in the rehabilitation process but can be difficult to plan and implement. It often follows on from a serious, acute event that significantly modifies personal independence. This new clinical situation is disorienting not only for the patient (whose life plan is changed) but also for his/her family, which must adapt to these new circumstances. Furthermore, the patient’s medical situation changes and he/she may consume more primary medical care and nursing resources. The general practitioner (GP) is an important stakeholder in home discharge but is often poorly prepared to deal with this type of patient . The issues are considerable and preparation of the hospital-to-home discharge is essential because a number of parameters have to be addressed: the environment into which the patient is discharged, the degree of coordination between the various stakeholders, the family and friends’ ability to anticipate and deal with potential crises and difficulties, and the provision of homecare under optimal conditions.

We particularly noted three literature reports on hospital-to-home discharge . The first is a report on a consensus seminar held on September 29th, 2004, by the French Society of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine (Sofmer) and the French High Authority for Health (HAS) concerning the organization and implementation of hospital-to-home discharge of adults with motor and/or neuropsychological disabilities. The five questions put to the seminar panel were as follows. What exactly is a discharge plan? How can we define a personalized discharge plan? In view of the currently available data, how can we organize and implement a personalized discharge plan for a handicapped person? Faced with the obstacles, limiting factors and the reciprocal expectations of all the stakeholders’ (in hospital and at home) concerned by the practical implementation of hospital-to-home discharge, what proposals can be made? How can we evaluate the therapeutic value of this procedure? The seminar sought to draw up guidelines on organizational aspects of hospital-to-home discharge for handicapped adult patients. The main recommendation was that successful hospital-to-home discharge depends on a seamless coordination process that starts in hospital. The consensus seminar recommended true cooperation between the hospital and private-practice physicians, based on well-defined tools that can be accessed by all the stakeholders in the discharge process. The second report is a HAS document (dated December 2003) on strategies for (and the organisation of) hospital-to-home discharge of adult stroke patients. These clinical practice guidelines were targeted at all healthcare and social care professionals and payers, with a view to better hospital-to-home discharge. The third is a report on a consensus seminar held by the HAS and the French society for health economics on December 9th, 2004, on the hospital-to-home discharge of adult patients with a high probability of motor or psychological dependence. The report included an analysis of the questions posed by various stakeholders in the hospital-to-home discharge process (financial aspects, organisational efficiency and the assessment of the patient’s and carers’ levels of satisfaction, for example). It is noteworthy that these guidelines reflected the hospital’s point of view more than that of primary care stakeholders (although a few of the latter were indeed questioned during the seminar).

Evaluation of hospital discharge is a challenge for both hospital-based and private-practice stakeholders. It is therefore essential to develop indicators that describe how the discharge is planned and its compliance with good practice. This evaluation is problematic on several levels, since the indicators will have to correspond to not only the expectations of the patient and his/her family but also those of non-hospital-based stakeholders in general and primary care physicians in particular.

Of course, each hospital-to-home discharge is different and depends on the individual situation; the discharge of a diabetic patient does not raise the same issues as that of a stroke patient. The situation of a caregiver-dependent patient is both specific (in terms of the requisite coordination between nurses, physiotherapists and other carers) and emblematic of the difficulties encountered. However, there are few literature data on organizational aspects of the discharge of handicapped patients in general and hospital-primary care coordination in particular. This is especially the case for “downstream” points of view, i.e. that of the GP. A few articles have addressed the organisation and evaluation of hospital-to-home discharge but these do not always focus on a particular medical condition , such as stroke or cancer. Furthermore, the level of dependence in these study populations appears to be heterogeneous. Hence, very few data are available on GPs’ expectations in terms of the organisation of the discharge process for caregiver-dependent patients. Based on the existing guidelines, we therefore drew up a list of items describing the organisation of the discharge process for a dependent patient. The list can be translated into simple, measurable indicators of the quality of hospital-to-home discharge. The objective of the present study was to see how GPs rated each of the criteria and whether the latter can be used in routine practice to improve hospital-primary care coordination and thus guarantee continuity of care and optimal hospital-to-home discharge.

1.2

Materials and methods

1.2.1

Population

We performed an anonymous postal survey of all the GPs based in the Maine-et-Loire county of France. We excluded GPs who solely practiced a particular medical specialty (sports medicine, acupuncture, homeopathy, angiology, echography, etc.).

1.2.2

Questionnaire

We developed a survey questionnaire on the basis of the Sofmer/HAS consensus seminar guidelines on planning and implementing the hospital-to-home discharge of adult patients with motor and/or neuropsychological disabilities . Initially, we defined 17 criteria. After review by several PRM physicians and the exclusion of redundancies, 14 criteria were selected ( Table 1 ). The questionnaire sent to each GP comprised three sections:

- •

the importance of each of the 14 items was evaluated on a visual analogue scale. The respondee was asked to place a vertical mark on a 10 cm-long horizontal line, at some point between the “not at all important” and “extremely important” boundaries. The respondees were allowed to omit answers if they so wished;

- •

the respondee then ranked the three main criteria in decreasing order of importance;

- •

respondees could reply freely to the last question: “Is there one or more other factors that you feel are important in hospital-to-home discharge?”.

| Item 1 | Contact with the GP, initiated by the PRM service |

| Item 2 | A surgery meeting between the GP and the patient’s family while the patient is in hospital |

| Item 3 | Provision of information to the GP by the PRM service concerning the patient’s discharge date |

| Item 4 | Consultation with the PRM physician in the month following the patient’s discharge |

| Item 5 | A clearly identified key contact person for the patient |

| Item 6 | Psychological support for the patient and his/her family |

| Item 7 | Training in activities of daily living for the patient and his/her family during hospitalization in the PRM service |

| Item 8 | Family involvement in rehabilitation during hospitalization |

| Item 9 | A visit to the patient’s home during hospitalization |

| Item 10 | A brief home stay by the patient during hospitalization |

| Item 11 | A multidisciplinary summary meeting between the various non-hospital-based stakeholders |

| Item 12 | A liaison notebook for the family, the hospital care team and the various non-hospital-based stakeholders following discharge |

| Item 13 | A list of people to be contacted in the event of problems encountered by the patient and his/her family during hospital-to-home discharge |

| Item 14 | An offer of respite hospitalization by the PRM service in the event of difficulties for the family and the patient at home |

1.2.3

Data analysis

The data were entered using Epidata 3.1 software . A descriptive analysis was performed in GraphPad Prism software (version 4.00 for Windows) . The statistical analysis determined the mean, standard deviation and median for each item (i.e. items 1 to 14). The distribution frequency of each item was then analyzed, so that they could be ranked in order of importance. We determined the three items rated as being the most important.

1.3

Results

1.3.1

The response rate

In all, 966 questionnaires were sent out and 104 were returned (yielding a response rate of 10.77%).

1.3.2

Descriptive analysis of the mean and median for each item

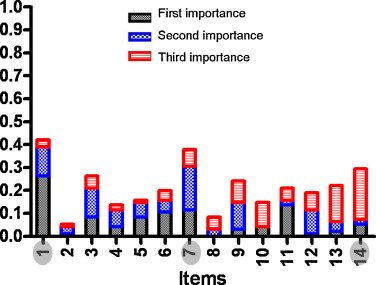

A meeting between the GP and the patient’s family while the patient is in hospital (item 2) was the item with the lowest median score (a score of 5) ( Fig. 1 , Table 1 ). A multidisciplinary summary meeting with the various non-hospital-based stakeholders (item 11) and family involvement in rehabilitation sessions during hospitalization (item 8) had median scores of 7.5 and 7.75, respectively. All other items had a median score of 8 or more. The items with a median of 9 or more were as follows: contact with the GP by the PRM service (item 1), the provision of information to the GP by the PRM service concerning the patient’s discharge date (item 3), training in activities of daily living for the patient and his/her family during hospitalization (item 7) and a list of people to be contacted in the event of problems encountered by the patient and his/her family during hospital-to-home discharge (item 13).

1.3.3

Rankings

In the present study, there was a homogeneous distribution of answers across the various items ( Fig. 2 ). The three items that were most frequently ranked in the top three were contact with the GP by the PRM service (item 1), training in activities of daily living for the patient and his/her family during hospitalization (item 7) and an offer of respite hospitalization by the PRM service in the event of difficulties for the family and the patient at home (item 14).

1.4

Discussion

One of the possible limitations of the present study relates to the low proportion of questionnaires returned by the GPs (104 replies out of 966 questionnaires posted). However, it is known that private-practice physicians receive a large number of postal questionnaires and have busy schedules; overall, our response rate (10.77%) is similar to those generally observed (between 10 and 20%) for this type of postal survey with no follow-up . One key strength of our study is that we were able to gather and analyze the opinions of over a hundred GPs, which thus constitutes a representative sample. We must also be cautious concerning our statements on less pertinent criteria, in as much as all items had a median score greater than 7.5 with the exception of item 2 (a surgery meeting between the GP and the patient’s family while the patient is in hospital, with a median score of 5). The GPs therefore judged that all but one of the suggested items were important. Furthermore, it is noteworthy that none of the respondees made any other suggestions in the last part of the questionnaire; this may indicate that our study indeed encompassed all the most relevant issues in the hospital-to-home discharge of carer-dependent patients. Four criteria had a median score greater than 9: contact with the GP by the PRM service (item 1), provision of information to the GP by the PRM service concerning the patient’s discharge date (item 3), training in activities of daily living during hospitalization (item 7) and the list of people to be contacted in the event of problems encountered by the patient and his/her family during hospital-to-home discharge (item 13). A fifth item (an offer of respite hospitalization by the PRM service in the event of difficulties for the family and the patient at home; item 14) was cited as being one of the three most important. These criteria correspond to two distinct goals. Items 1, 3 and 13 characterise good hospital-private practice coordination but are nevertheless not specific for discharge from a PRM service. Items 7 and 14 are more directly related to dependency. Of the non-specific items, the discharge date and contact with the GP by the PRM service (items 1 and 3) were judged to be particularly important in planning and ensuring continuity of care. This agrees with the 2003 HAS guidelines on continuity of care and the need to send the GP a patient management report within 7 days. This is even more important in light of the results of a 2009 study on hospitals’ provision of medical information to GPs in the city of Paris and the Seine-Saint-Denis county showing that for hospitalizations as a whole, only half of the GPs received a hospitalization report and 32% had not been advised of their patient’s discharge from hospital. Having a list of people to contact in the event of problems during hospital-to-home discharge (item 13) is not specific for the discharge of a dependent patient but was considered to be an essential element by our survey population. In fact, GPs often have trouble contacting the right person in the event of problems at home. One group of criteria and indicators thus addressed the organisation aspects of all types of hospital discharge. Two of these criteria (items 1 and 3) are explicitly mentioned in the first version of the accreditation manual published by the HAS in 2003 . It is stated that the patient’s discharge must be planned and coordinated; to this end, the attending GP must be informed about hospitalization and discharge before the latter occurs. Item 13 does not appear in the accreditation manual.

In terms of dependency-specific items, training in activities of daily living for the patient and his/her family during hospitalization in the PRM service (item 7) was judged to be important by the GPs – more so than family involvement in rehabilitation sessions (item 8). This doubtless corresponds to the demands placed on the family in activities of daily living (transfers, meals and even washing and dressing). In turn, the family primarily contacts the GP in the event of a problem at home. In contrast, r ange of motion exercise, memory stimulation and so on are performed by healthcare professionals at defined times after hospital-to-home discharge; these probably involve the PRM physician more than the GP. Furthermore, the primary care physician may consider him/herself to be poorly informed of these issues and poorly trained to deal with some of these situations ; this may also explain the fact that GPs consider item 8 to be relatively unimportant. However, these two items are at the heart of the patient education process that, according to the World Healthcare Organization, seeks to help patients with chronic disease to learn or maintain the skills that they need to best manage their life. Furthermore, the HAS has published a document (including guidelines) on patient education in which the two ultimate goals are defined: (i) the learning and maintenance of self-care skills (such as symptom relief and the performance of technical or care-related procedures) and (ii) the stimulation or acquisition of skills for coping (such as self-confidence and self-knowledge). In our context of carer-dependent patients, healthcare professionals may have trouble addressing these goals in routine practice. In fact, this type of programme cannot solely involve the patient; family members and carers have an important role in this respect. Their involvement in training in the activities of daily living and in rehabilitation sessions is essential for improving quality of life for the patient and his/her family. This also involves provision of assistance to the carers themselves, on whom a significant burden is placed in this type of situation.

Item 14 concerned the offer of respite hospitalization by the PRM service in the event of difficulties for the patient or the family at home. Indeed, primary care physicians (along with other non-hospital-based stakeholders) are directly confronted with difficulties that may occur once the patient has returned home; sometimes, the GP does not know whom to contact or where to send the patient for respite hospitalization. In contrast, it is noteworthy that this item was most often ignored by the respondees (13.5%). These two dependency-specific items do not appear in the accreditation manual .

Other criteria that could have characterized specific organisational aspects of private-practice care of these patients [such as a meeting between the GP and the family during hospitalization (item 2), a multidisciplinary summary meeting between the various non-hospital-based stakeholders (item 11) and the use of liaison notebooks (item 12)] obtained the lowest scores. Several possible explanations come to mind. A questionnaire sent by a hospital department may have been an opportunity for GPs to better express their expectations of the hospital, rather than to give their own suggestions for better organization of primary care. The logistic and regulatory conditions of primary care medicine (notably the absence of financial incentives for performing coordination activities) are probably also explanatory elements. According to the GPs, item 2 was the least important (whether in terms of the median score or the ranking frequency). Hence, the surveyed GPs appeared to have a fairly uniform vision of obstacles and solutions in the continuity of care. Item 2 was doubtless the least convincing in terms of care coordination and continuity. We were also surprised to find that psychological support (item 6), a key contact person for the patient (item 5) and family involvement in rehabilitation (item 8) were not thought to be particularly important. Even though the GPs acknowledged the family’s role in daily care, they were less ready to acknowledge the role of the patient and his/her family in the more technical aspects of care organization – perhaps because the GP does not consider him/herself an expert in this respect . One can also wonder whether the primary care physicians omitted to choose these items because they were thinking about patients with impaired decision-taking ability, rather than those dependent on carers. We have the impression that GPs do not spontaneously suggest strategies for patient empowerment (defined as sharing power with a patient who, with the provision of appropriate technical knowledge and psychological support, is able to take healthcare decisions).

The results of the present study prompt us to suggest three types of quality indicator for organisation procedures in hospital-to-home discharge. The first concerns the transmission of non-specific information (items 1 and 3), which are essential items. Communication with the attending physician during a long period of hospitalization cannot be summarized by a mere discharge note. The objective could be systematic phone or e-mail contact with the attending physician during hospitalization, along with a hospitalization report and a discharge date note. It would be easy to build an indicator measuring the percentage of attending physicians actually contacted and the number of GPs actually informed of the discharge date. This would help to plan the patient’s return home and is in line with the expert seminar on care pathways for stroke patients , which recommended the provision of (i) information about stroke for the carer and (ii) information on appropriate, valid techniques for the stroke patient.

The second type of criterion concerns the training provided to carers and the offer of respite hospitalization. These criteria again require the development of specific patient education programmes, evaluation tools and indicators (the number of patients and families trained in the activities of daily living; the number of patients and families informed during the stay in the PRM service, information about possible respite hospitalization and appropriate providers [local hospitals, retirement homes, etc.]). In some specific fields (such as cancer, palliative care and brain damage) and some regions of France , there are some very practical patient guides which provides contact details for each hospital-based stakeholder. These two categories of criterion encompass the most relevant items, according to the GPs surveyed in the present study. The third category includes criteria which are still not key concerns for GPs. They correspond to either very significant modifications in private-practice care procedures or an empowerment model that is clearly not yet predominant.

1.5

Conclusion

The results of our study show that (according to GPs) the hospital-to-home discharge of dependent people does not differ greatly from the discharge of patients hospitalized for other reasons. Of the five most relevant items selected by the GPs, three are hardly specific for dependent people and are mainly related to general aspects of private practice-hospital coordination. The present study investigated the opinion of a single group of stakeholders in hospital-to-home discharge and it is difficult to say whether the surveyed GPs classified these indicators as relevant because (i) the items were indeed important for the patient and for continuity of care, (ii) the items were easy to implement and well-suited to the physicians’ routine practice or (iii) the GPs did not feel that they were sufficiently well informed to comment on other items. It will therefore be necessary to complete the present work by recording the opinions of other stakeholders (notably patients, their families and homecare service providers) and establish whether implement of these criteria indeed improves hospital-to-home discharge and hospital-GP continuity of care.

Disclosure of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest concerning this article.

2

Version française

2.1

Introduction

Le retour à domicile d’un patient dépendant d’aides humaines sortant d’une hospitalisation d’un service de médecine physique et de réadaptation (MPR) est une étape essentielle du processus de réadaptation qui peut être difficile à organiser. Elle fait souvent suite à la survenue d’un événement aigu grave modifiant profondément l’autonomie de la personne. Il apparaît donc une nouvelle situation clinique, déstabilisante pour le patient qui voit ses projets de vie changer, mais aussi pour la famille qui doit s’adapter à cette situation. Par ailleurs, la situation médicale du patient change également, il peut devenir plus consommateur de soins médicaux primaires et infirmiers. Le médecin référent, souvent déstabilisé par ce type de patient , est un acteur important du processus qui assurera le retour à domicile. Les enjeux sont importants et la préparation de la sortie est essentielle car il faut s’assurer du choix du lieu de retour du patient, de la coordination entre les différents intervenants, de la capacité de la famille et des proches à aider et anticiper les éventuelles crises et difficultés, pour garantir un maintien à domicile dans les meilleures conditions possibles.

Dans la littérature actuelle, nous avons relevé trois travaux sur le retour à domicile . Le premier est une conférence de consensus du 29 septembre 2004, de la Société française de médecine physique et de réadaptation (Sofmer) et de la Haute Autorité de santé (HAS) concernant le projet de sortie du monde hospitalier et le retour à domicile d’une personne adulte handicapée sur les plans moteur et/ou neuropsychologique. Les cinq questions posées au jury étaient : qu’est ce qu’un projet de sortie ? Comment définir de façon personnalisée le projet de sortie ? Selon les données actuelles, quelle organisation pour la mise en œuvre pratique et la réalisation du projet de sortie individualisé, dans le contexte de la vie de la personne handicapée ? Face aux obstacles, aux facteurs limitants et aux attentes réciproques de tous les acteurs (de l’hôpital et du lieu de vie) concerné par la réalisation pratique de la sortie de l’hôpital et du retour à domicile, quelles propositions ? Comment évaluer le service rendu ? L’objectif de la conférence était de proposer des recommandations sur le projet de sortie d’un patient adulte handicapé. La recommandation principale concluait finalement que la réussite d’un projet de sortie repose surtout sur la continuité de la coordination débutée à l’hôpital. Cette conférence de consensus recommande donc une véritable coopération entre professionnels hospitaliers et de ville qui devrait reposer sur des outils concrets et accessibles à tous les acteurs du retour à domicile. Le deuxième est un travail de l’HAS de décembre 2003 sur les stratégies et organisation du retour au domicile des patients adultes atteints d’accident vasculaire cérébral (AVC). Ces recommandations pour la pratique clinique s’adressent à tous les professionnels de santé et sociaux ainsi qu’aux organismes de financement pour organiser le mieux possible un retour à domicile. Le troisième est une conférence de consensus de l’HAS et de la société de l’économie de la santé du 9 décembre 2004 sur la sortie du monde hospitalier et retour à domicile d’une personne adulte évoluant vers la dépendance motrice ou psychique. Ce travail propose une analyse des questions posées par différents acteurs du retour à domicile de ces patients (modalité de financement, efficacité de l’organisation, évaluations de la satisfaction du patient et des aidants par exemple). On peut remarquer ici que les recommandations concernent plus le point de vue hospitalier que celui des acteurs de soins primaires (même si quelques uns d’entre eux ont été interrogés dans ces réflexions).

L’évaluation de la sortie du monde hospitalier est un challenge autant pour la médecine hospitalière que pour la médecine de ville. Il sera donc nécessaire que soient développés des indicateurs permettant de décrire l’organisation de cette sortie et sa conformité à des éléments de bonne pratique. La difficulté de cette évaluation se joue à plusieurs niveaux. Les indicateurs qui seront développés peuvent correspondre à des attentes du patient et de sa famille, mais aussi des acteurs des soins de ville et, notamment, des médecins de soins primaires.

Chaque retour à domicile est, bien entendu, différent et le problème se pose différemment selon les situations (le retour à domicile d’un patient diabétique ne pose pas la même problématique que le retour à domicile d’un patient atteint d’un AVC). La situation du patient dépendant d’aides humaines est à la fois spécifique par la coordination avec les services de soins infirmiers, les kinésithérapeutes, etc. et emblématique des difficultés rencontrées. Or, les données de la littérature en matière de projet de sortie d’un patient handicapé, notamment en ce qui concerne la coordination entre milieu hospitalier et médecine de ville, sont peu nombreuses, d’autant plus lorsqu’il s’agit d’évaluer le point de vue d’aval, c’est-à-dire celui des médecins traitants. Quelques articles sont disponibles concernant l’organisation et l’évaluation du retour à domicile de patients mais il s’agit toujours de travaux portant sur une pathologie précise (AVC, cancer). Les niveaux de dépendance apparaissent hétérogènes dans ces populations. Ainsi, très peu de données sont disponibles sur les attentes des médecins traitants concernant l’organisation du retour à domicile de patients dépendants d’aides humaines. À partir des recommandations existantes nous avons donc établi une liste de critères décrivant l’organisation de la sortie d’un patient dépendant, qui puisse être traduite sous la forme d’indicateurs de la qualité du retour à domicile, simples et mesurables. L’objectif de ce travail est d’évaluer, auprès d’une population de médecins de soins primaires, l’importance qu’ils accordent à chacun des critères et de savoir comment les utiliser en pratique quotidienne pour améliorer la coordination entre milieux hospitalier et ambulatoire afin de garantir une bonne continuité des soins et un bon retour à domicile.

2.2

Matériel et méthode

2.2.1

Population

Il s’agit d’une enquête auprès de médecins généralistes (MG). Ces médecins ont été sollicités par courrier et nous avons souhaité nous approcher de l’exhaustivité du territoire de santé du Maine et Loire. Nous avons sollicité de façon anonyme tous les MG du département à l’exclusion de ceux exerçant de façon exclusive un mode d’exercice particulier (médecine du sport, acupuncture, homéopathie…) ou une spécialisation (angiologie ou échographie).

2.2.2

Questionnaire

Nous avons élaboré un questionnaire d’enquête à partir des recommandations émises par la Sofmer et la HAS sur le projet de sortie du monde hospitalier et le retour à domicile d’une personne adulte handicapée sur les plans moteur et/ou neuropsychologique dans une conférence de consensus du 29 septembre 2004 .

Initialement nous avons défini 17 critères. La relecture par plusieurs médecins de MPR a conduit à en retenir 14 après exclusion des redondances ( Tableau 1 ).