CHAPTER 12 Imaging of the Pediatric Elbow

INTRODUCTION

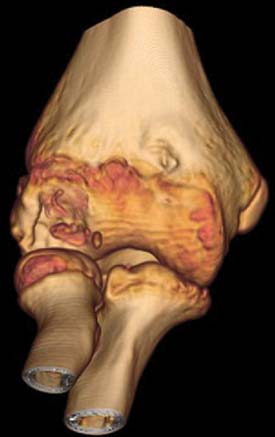

Tomography, using either a simple linear method or a complex motion system, can be used in the evaluation of growth plates that have closed prematurely following trauma. In most practices, computed tomography has completely replaced conventional tomography. Computed tomography examinations now take only seconds to perform, and sedation is usually not necessary, even in very young infants and children. Using current 64-slice multidetector computed tomography technology (MDCT), isovoxel images can be obtained in all three planes down to 0.6-mm collimation. This allows detailed imaging, with the bony trabecular pattern well seen. Examinations are obtained with the patient in the prone position, with the affected arm held above the head with about 90 degrees of flexion at the elbow. Sagittal and coronal two-dimensional reformatted images as well as three-dimensional reconstructions are then made from the raw data. MDCT is a sensitive (92%) and specific (79%) method of evaluating for radiographically occult elbow fractures.6 MDCT can also use automated tube current modulation to markedly decrease the radiation dose to the patient compared with fixed-tube current techniques. MDCT can also be performed with no image degradation through a cast.3 MDCT with reformatting can better delineate intra-articular fractures (Fig. 12-1). Three-dimensional imaging can also provide additional information and help define the joint relationships to aid surgical planning (Figs. 12-2 and 12-3). The resulting three-dimensional image can be rotated in all planes with computerized subtraction of the adjacent soft tissues and bones, if needed.

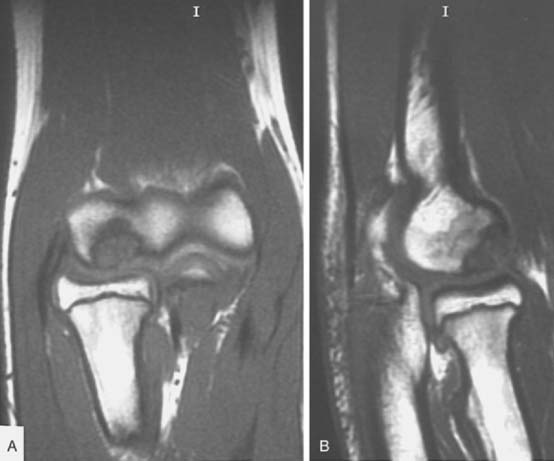

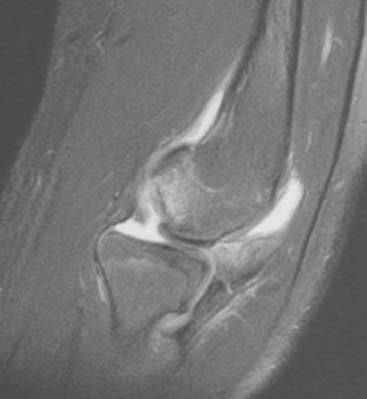

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and ultrasonography are increasingly being used to evaluate the elbow. MRI can evaluate cartilage, bone marrow, and soft tissue structures (Fig. 12-4).8 Radiographs do not show bone bruising, or cartilaginous or soft tissue injury and can underestimate physeal injury. MRI is also occasionally used to better define elbow fractures.2 Owing to the length of the MRI examination (at least 20 minutes), children younger than 5 years old will usually need sedation so that optimal MRI images can be obtained. In children with elbow trauma, MRI reveals a broad spectrum of bone and soft tissue injury, including ligamentous injury, beyond that recognized by radiographs. However, the additional information afforded by MRI usually does not change treatment or clinical outcome in acute elbow trauma.9 MRI can be very useful in the evaluation of osteochondritis dissecans (OCD) of the capitellum. MRI provides information about the size, location and stability of the OCD lesion. All of these factors are important when deciding treatment options (see Chapter 20 for more discussion). Unstable OCD lesions in the capitellum have a peripheral rim of high signal or an underlying fluid-filled cyst on T2-weighted images (Fig. 12-5). Stable OCD lesions have no peripheral signal abnormality.12 Loose bodies in the elbow joint can be visualized by MRI or MDCT, but smaller detached bone fragments are usually better visualized using MDCT (Fig 12-6).

Ultrasonography has the ability to dynamically delineate soft tissues and cartilage in detail.13 Soft tissue swelling, a mass (including vascular masses investigated with duplex Doppler and color flow Doppler), joint effusion, and fractures, particularly in infants and young children with unossified or minimally ossified epiphyses, are studied with this modality.1,7 Ultrasound can detect early changes of medial epicondylar fragmentation and OCD of the capitellum, even in the asymptomatic stage in selected populations such as young baseball players.10

As with other portions of the appendicular and axial skeletons, side-to-side comparison may be helpful when one is presented with an unfamiliar or a rare variant. Comparison views need to be obtained only in selected cases,14,15 such as when consultation with the standard text of normal cases is not helpful.5,11,17

NORMAL DEVELOPMENT

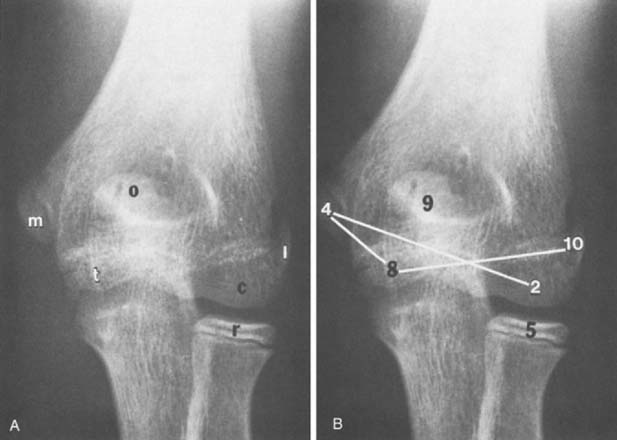

The maturation sequence at the elbow is more variable than that of the hand and wrist. Nonetheless, an appreciation of the normal sequence and timing of the appearance of ossification centers and maturation patterns is important for an understanding of the radiographic appearances of the elbow in children (Fig. 12-7). Several mnemonics have been suggested to help remember the time of appearance of the ossification of these centers. We find that the cross-connecting ossification centers (see Fig. 12-7B) are particularly helpful in remembering at least the order of ossification of these centers. An atlas entitled Radiology of the Pediatric Elbow5 shows standards for elbow maturation in children. To consistently evaluate the developing elbow, one must analyze each of the secondary centers of ossification, accounting for its appearance, configuration during development, and associated changes as it matures and eventually fuses with the humeral shaft. The descriptions that follow are brief, but they outline the major points of development and maturation of the centers.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree