Chapter 52 Herbs and Other Dietary Supplements

Trends in Supplement Use: Family Physician’s Role

Specifically asking about herb and other supplement use when gathering a patient history is essential, given that patients may not always volunteer this information. Helping patients make choices regarding supplement use often involves negotiation. Of 1196 supplement users, 66% stated that they would keep taking the supplement they were taking most often, even if the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) reported it as ineffective (Blendon et al., 2001). People who take supplements often value their independence in making health care decisions, and many have spent much time researching various products online. Table 52-1 summarizes findings on the reasons people give for taking dietary supplements. Many supplements have been used for thousands of years, and for some patients, this alone constitutes evidence that supplements are safe and beneficial. Native Americans had medicinal uses for more than 2500 different plant species (Moerman, 1998), and various “supplements” have been used as part of traditional medical practices in most cultures throughout history. In the United States before 1930, herbs constituted a significant proportion of the remedies listed in the United States Pharmacopeia (Blumenthal, 2003).

Table 52-1 Main Reasons Patients Use Dietary Supplements

| Kennedy (2007)∗ (n = 23,393 adults) | ConsumerLab.com† (n = 3226) | Kaufman et al.‡ (n = 2590) |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Back pain | 1. General health (67%) | 1. “To supplement the diet” (45%) |

| 2. Neck pain | 2. Colds (53%) | 2. General health (16%) |

| 3. Joint pain (5.2%) | 3. Osteoarthritis (39%) | 3. Arthritis (7%) |

| 4. Arthritis (3.5%) | 4. Energy enhancement (37%) | 4. Memory impairment (6%) |

| 5. Anxiety (2.8%) | 5. Cholesterol control (29%) | 5. Energy (5%) |

| 6. Cholesterol (2.1%) | 6. Cancer prevention (28%) | 6. Immune system enhancement (5%) |

| 7. Head/chest cold (2.0%) | 7. Allergies (27%) | 7. Other joint issues (4%) |

| 8. Other musculoskeletal conditions (1.8%) | 8. Weight management (25%) | 8. Sleep aid (3%) |

| 9. Severe headache or migraine (1.6%) | 9. Prostate problems (3%) |

As often occurs with complementary and alternative/integrative medicine (CAM) modalities, use is most common for disorders (often chronic) that Western medical approaches may not be able to treat as safely or effectively.

∗ National Health Information Survey of reasons for CAM use in general, 2008.

† In 2002 study on reasons for supplement use, 54% of respondents indicated they were taking supplements for four or more simultaneous conditions. Respondents could give multiple reasons for taking supplements. Respondents were users of the ConsumerLab.com website and likely high-frequency herb users.

‡ Results are based on a 2002 telephone survey of why people take supplements. The definition of “supplement” used for respondents excluded vitamins and minerals; 25% answered either “don’t know” or “no reason specified” when asked about supplement use. Respondents could give multiple reasons for taking supplements.

Only in recent decades have more scientifically based studies of supplement efficacy and safety been conducted. With the development of the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM) in October 1998 within the National Institutes of Health (NIH), supplement research funding in the United States has grown dramatically. In other countries, groups such as the European Scientific Cooperative on Phytomedicines (ESCOP, www.escop.com) and Edzard Ernst’s team at the University of Exeter have been gathering and analyzing data from hundreds of well-designed randomized trials. It is no longer legitimate during a patient encounter to make sweeping statements discouraging supplement use because, “We just don’t know enough about them.” To state that all supplements are dangerous is just as inaccurate as claiming, as many manufacturers do, that dietary supplements are consistently safe and effective. Some supplements have shown great promise in helping to prevent or treat various illnesses. Others have been proven harmful enough that their use should be discouraged. Ideally, physicians should be as informed and actively involved in patients’ decisions regarding dietary supplements as they are with their decisions regarding prescription medications. Box 52-1 offers guidelines for discussing supplements with patients.

Box 52-1 Considerations When Evaluating Supplement Safety

Data from Blumenthal M. American Botanical Council. The ABC Clinical Guide to Herbs. New York, Thieme, 2003; Brinker F. Herb Contraindications and Drug Interactions, 3rd ed. Sandy, Ore, Eclectic Publications, 2001; NIH Office of Dietary Supplements, 2009; Natural Medicines Comprehensive Database, 2009; and Rotblatt M, Ziment I. Evidence-Based Herbal Medicine. Philadelphia, Hanley & Belfus, 2002.

Supplement Safety

Patients should be encouraged to bring the supplements they are taking with them to clinic visits. They should be reminded to list supplements whenever they list their medications, particularly on hospital admission. Often, patients will hand their physician the packaging for a particular product; Box 52-2 discusses how to evaluate a product’s quality based on its packaging information.

Box 52-2 Considerations When Reviewing a Supplement’s Packaging

Data from Blumenthal M. American Botanical Council. The ABC Clinical Guide to Herbs. New York, Thieme, 2003; Brinker F. Herb Contraindications and Drug Interactions, 3rd ed. Sandy, Ore, Eclectic Publications, 2001; NIH Office of Dietary Supplements, 2009; Natural Medicines Comprehensive Database, 2009; and Rotblatt M, Ziment I. Evidence-Based Herbal Medicine. Philadelphia, Hanley & Belfus, 2002.

The challenges associated with placing the burden of proof for product safety on the FDA surfaced with the events leading to the April 2004 ban on ephedra, a naturally derived, amphetamine-like stimulant. Only after linking ephedra to 155 deaths, including the death of a well-known athlete, and dozens of heart attacks and strokes was the FDA finally able to justify putting the ban into effect (Natural Database, 2009; Wong, 2009). Ephedra has been used in various forms in China for thousands of years, but not at the high dosage levels found in many of the products linked to harmful outcomes. Many of the negative effects of ephedra were associated with its use in combination with other compounds, such as caffeine. Some supplement manufacturers seem to assume that “if a little bit is good, more is even better.” Table 52-2 summarizes some herbal supplements that, based on the current level of research, should be avoided or used only under professional supervision.

Table 52-2 Potentially Dangerous Supplements∗

| Herb Names | Why Avoid |

|---|---|

| Herbs that Are Generally Contraindicated | |

| Contains aristolochic acid, a carcinogen and known cause of renal failure. Deaths have been attributed to consumption | |

| Wild ginger (Asarum canadense) | Banned in seven European countries, Egypt, Japan, and Venezuela |

| Germander (Teucrium chamaedrys) | |

Liver damage; but as is often the case, this was likely caused by a specific product that contained adulterants. | |

| Herbs Rated as Likely Hazardous (Adverse Event Reports or Theoretic Risk) | |

| Liver damage | |

FDA, U.S. Food and Drug Administration; CNS, central nervous system; MI, myocardial infarction.

∗ Herbs listed are still widely available in several over-the-counter products. Many of these herbs have been used safely for millennia by skilled herbalists providing individualized care. Should not be used without supervision by a knowledgeable herbalist or other skilled professional.

Data from Twelve Supplements You Should Avoid. Consumer Reports, May 2004, p 15; Basch EM, Ulbricht CE. Natural Standard Herb and Supplement Handbook: The Clinical Bottom Line. Boston, Elsevier-Mosby, 2005; and Brinker F. Herb Contraindications and Drug Interactions, 3rd ed. Sandy, Oregon, Eclectic Publications, 2001.

Herb-Drug Interactions

One of the most common adverse effects of many herbal remedies is alteration of coagulation. Levels of warfarin, heparin, or antiplatelet agents are altered by some herbs. Box 52-3 lists common supplements that affect coagulation and fibrinolysis. Box 52-4 lists herbs that may affect serum glucose levels, and Box 52-5 lists herbs with potential effects on blood pressure. A recent review of available case studies summarizes possible interactions among several popular herbal remedies, including echinacea, garlic, ginkgo, ginseng, kava, saw palmetto, and St. John’s wort (Izzo and Ernst, 2009).

Box 52-3 Effects of Common Herbs on Coagulation∗

Data from Basch EM, Ulbricht CE. Natural Standard Herb and Supplement Handbook: The Clinical Bottom Line. Boston, Elsevier-Mosby, 2005; Brinker F. Herb Contraindications and Drug Interactions, 3rd ed. Sandy, Ore, Eclectic Publications, 2001; and Natural Medicines Comprehensive Database. http://www.naturaldatabase.com. Accessed November 2009.

Increased Potential for Hemorrhage

Increased Heparin or Warfarin Effect

| Borage seed oil | Garlic |

| Danshen root | Ginkgo leaves |

| Devil’s claw | Papain (papaya) |

Box 52-4 Supplements that Can Alter Serum Glucose Levels∗

Data from Basch EM, Ulbricht CE. Natural Standard Herb and Supplement Handbook: The Clinical Bottom Line. Boston, Elsevier-Mosby, 2005; and Brinker F. Herb Contraindications and Drug Interactions, 3rd ed. Sandy, Ore, Eclectic Publications, 2001.

Box 52-5 Herbs that May Alter Blood Pressure∗

Data from Basch EM, Ulbricht CE. Natural Standard Herb and Supplement Handbook: The Clinical Bottom Line. Boston, Elsevier-Mosby, 2005; and Brinker F. Herb Contraindications and Drug Interactions, 3rd ed. Sandy, Oregon, Eclectic Publications, 2001.

Types of Supplements

Herbal Remedies

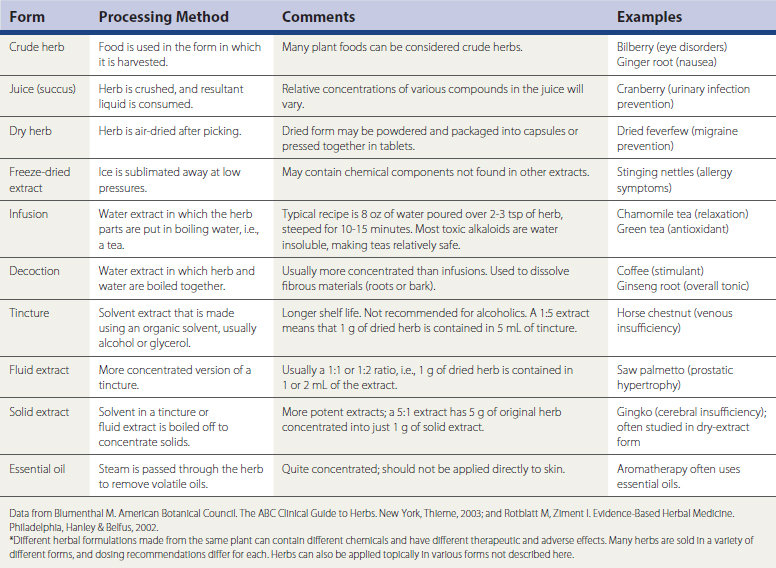

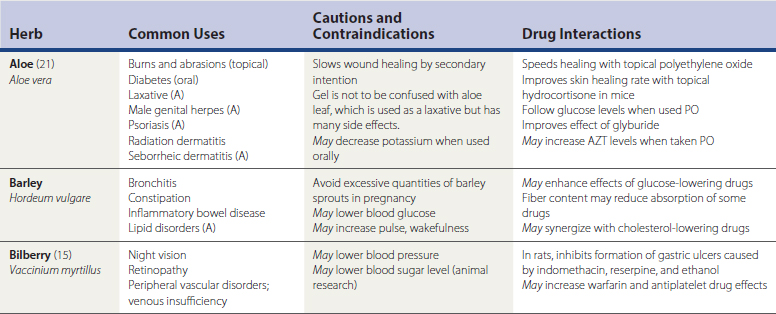

Herbal remedies, or botanicals, are supplement preparations made from various plant components. Herbals typically contain numerous chemical compounds. One study found that 34% of the U.S. population used herbal remedies at least once, and 14% took at least one herbal remedy consistently from June 2002 to June 2003 (Rogers, 2005). Chinese herbs, Ayurvedic herbs, and Latin American herbs are frequently used, but the great number of available herbs from around the world is not the only issue to discuss with patients. A given remedy’s potency and efficacy are influenced by where an herb was grown, the particular species used in the formulation, how the plant products were processed, which plant parts were used, and which compounds were used for chemical standardization. Table 52-3 lists common forms of herbal preparations. Table 52-4 lists some of the most common individual herbs, with indications, efficacy, and potential adverse effects and drug interactions.

Vitamins and Minerals

Table 52-5 lists several vitamins and minerals, their uses, contraindications, and efficacy information when available. Dose recommendations for vitamins and minerals are now referred to as reference daily intakes (RDIs) and continue to be debated, especially for certain trace minerals. (For a full list of RDIs and food sources of various nutrients, see Mahan et al., 2004.)

Table 52-5 Vitamin and Mineral Supplements∗