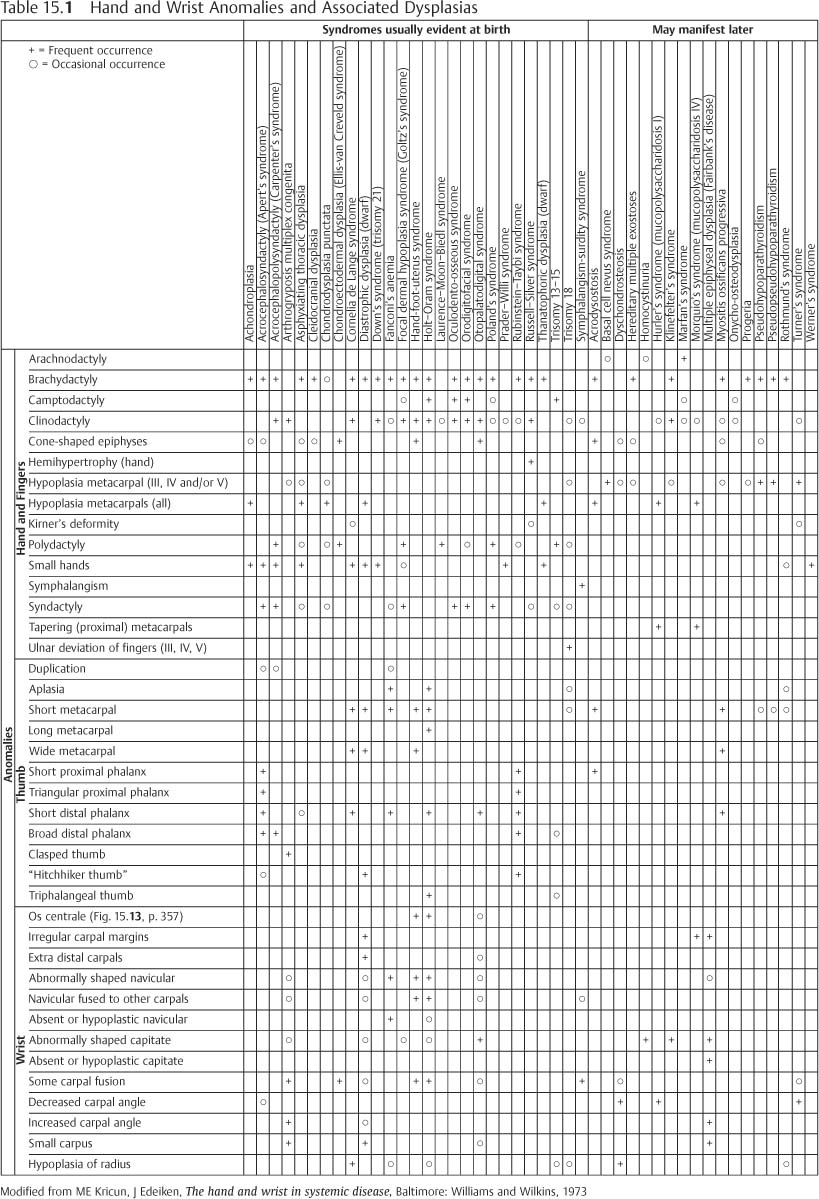

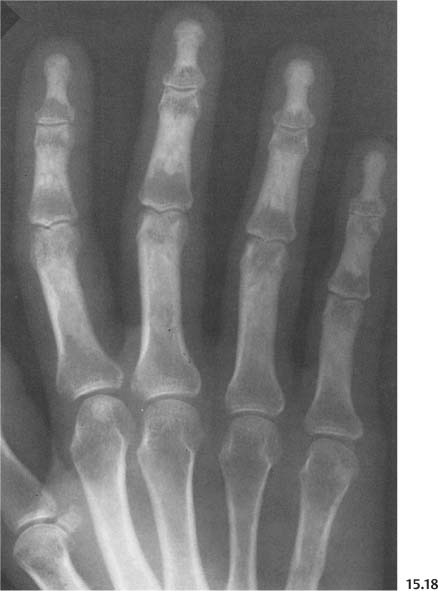

15 Hands and Feet There are 106 bones in the hands and feet, which is more than 50% of the total number of bones (206) in the entire skeleton. These bones, therefore, reflect fairly accurately both normal skeletal development and congenital or acquired disorders of the peripheral skeleton. Minor changes are better visualized in the hands and feet than in the more central skeleton. These provide early diagnostic sign in generalized arthritic and metabolic diseases. Several measurements are useful in the examination of the radiograph of the hand and wrist: (1) Metacarpal sign: A line tangential to the heads of the fourth and fifth metacarpals normally extends distal to the head of the third metacarpal. A positive metacarpal sign is present when the line passes through the head of the third metacarpal (Fig. 15.1). Positive metacarpal sign occurs in such disorders as pseudo-and pseudopseudohypoparathyroidism (Figs. 15.2 and 15.8), gonadal dysgenesis (Turner’s syndrome), basal cell nevus syndrome, multiple epiphyseal dysplasia, Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome, juvenile rheumatoid arthritis, sickle-cell anemia with infarction, trauma, and neonatal hyperthyroidism. (2) Metacarpal index: The ratio of the length to width at midshaft of metacarpals two to five varies from 5.4 to 7.9. In arachnodactyly (Marfan’s syndrome), it is more than eight (Fig. 15.3). (3) Carpal angle: The angle between two lines: the first tangent to the proximal surfaces of the scaphoid and lunate, the second tangent to the proximal margins of the triquetrum and lunate (Fig. 15.4) in a normal white population, it ranges from 120 to 150 degrees. It may be abnormal in several congenital syndromes. Many anomalies of the hands and feet are isolated without any association with a syndrome, but when detected, a possible constitutional condition should be sought. A detailed discussion of various bone dysplasias of infancy is beyond the scope of this text. Radiographs of the hand have such an important role in the differential diagnosis of many constitutional conditions that it was felt imperative to include a short summary of hand, wrist and foot anomalies and associated conditions (Tables 15.1 and 15.2). For the proper understanding of Tables 15.1 and 15.2, less common terms used are explained here*: Fig. 15.1 Positive metacarpal sign in Turner’s syndrome. The terminal tufts have a drumstick appearance. Fig. 15.2 Pseudopseudohypoparathyroidism. Short metacarpals and phalanges, with strongly positive metacarpal sign due to very short metacarpals 4 and 5. Fig. 15.3 Metacarpal index over eight in arachnodactyly. Fig. 15.4 Normal carpal angle.

Congenital Anomalies

Brachydactyly | = | shortening of phalanx or phalanges (Figs. 15.5 and 15.6) |

Brachymetacarpaly | = | shortening of metacarpal (s) (Fig. 15.7) |

Camptodactyly | = | permanent flexion of finger (s) (Fig. 15.13 and 15.14) |

Clinodactyly | = | curvature of (usually fifth) finger in a mediolateral plane (Figs. 15.9 and 15.10) |

Diastrophic | = | twisted |

Dysplasia | = | intrinsic growth disturbance |

Polydactyly | = | supernumerary digits (Fig. 15.11) |

Symphalangism | = | end-to-end fusion of contiguous phalanges (absent joint) |

Syndactyly | = | soft-tissue or bony union between adjacent digits (Fig. 15.9) |

The foot, as much as the hand, may yield useful information in the study of generalized congenital disorders. In certain conditions, the radiographic finding may be most characteristic in the foot. Many congenital syndromes involve some foot abnormality, but Table 15.2 is limited to those disorders in which the foot findings are an important part of the syndrome or are unique or unusual.

* Some other features mentioned in Tables 15.1 and 15.2 are further illustrated in Figs. 15.12–15.

Fig. 15.5 Achondroplasia. Short metacarpals and phalanges with wide epiphyses.

Fig. 15.6 Cretinism. Short metacarpals and slightly shortened phalanges. Fusion of epiphyseal plates at the age of 26.

Fig. 15.7 Brachymetacarpaly. Short metacarpals IV and V on the right and IV on the left. Incidental finding without constitutional abnormalities.

Fig. 15.8 Pseudohypoparathyroidism. Short metacarpals 4 and 5, as well as short distal phalanges and abnormally shaped carpal bones.

Fig. 15.9 Multiple anomalies in the hands of a 2-year-old child: 1 clinodactyly, 2 syndactyly with bony fusion of distal phalanges of fingers 3 and 4, 3 syndactyly with only soft-tissue fusion of fingers 3 and 4.

Fig. 15.10 Kirner’s deformity in the distal phalanges of both 5th fingers. This produces a distal medial curvature like clinodactyly. Incidentally the patient also has hyperparathyroidism with subperiosteal tunneling and frank erosion of the radial side of the second phalanx of the index fingers (arrows).

Fig. 15.11 Polydactyly. A supernumerary, rudimentary 6th finger.

Fig. 15.12 Aplasia of 1st metacarpal and thumb. A case of Fanconi’s anemia.

Fig. 15.13 Severe anomalies in a cleft hand: 1 Camptodactyly of the thumb. 2 abnormal shape of capitate with fusion of capitate and hamate, 3 partial fusion of two metacarpals with fracture of the union, 4 uniphalangeal hypoplastic finger, 5 short distsal phalanx, 6 aplasia of two metacarpals and fingers, and 7 os centrale (arrow)

Fig. 15.14 Anomalies in the hand bones. 1 Camptodactyly of the index finger, 2 hypertrophic finger with wide proximal phalanx articulating with two adjacent metacarpals, one of which has an abnormal, cone-shaped epiphysis (3), and 4 short distal phalanx of the thumb with a cone-shaped epiphysis.

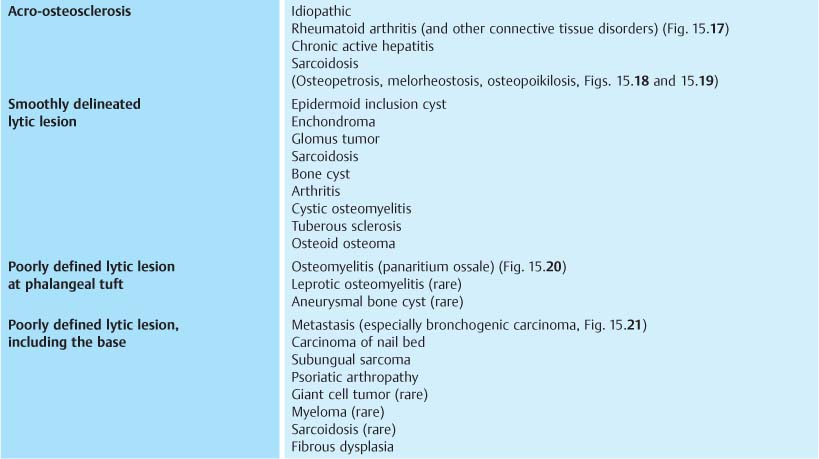

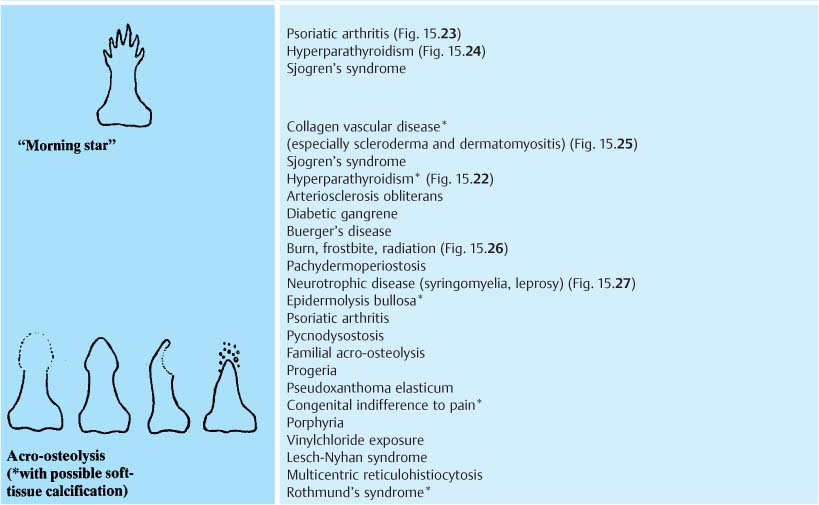

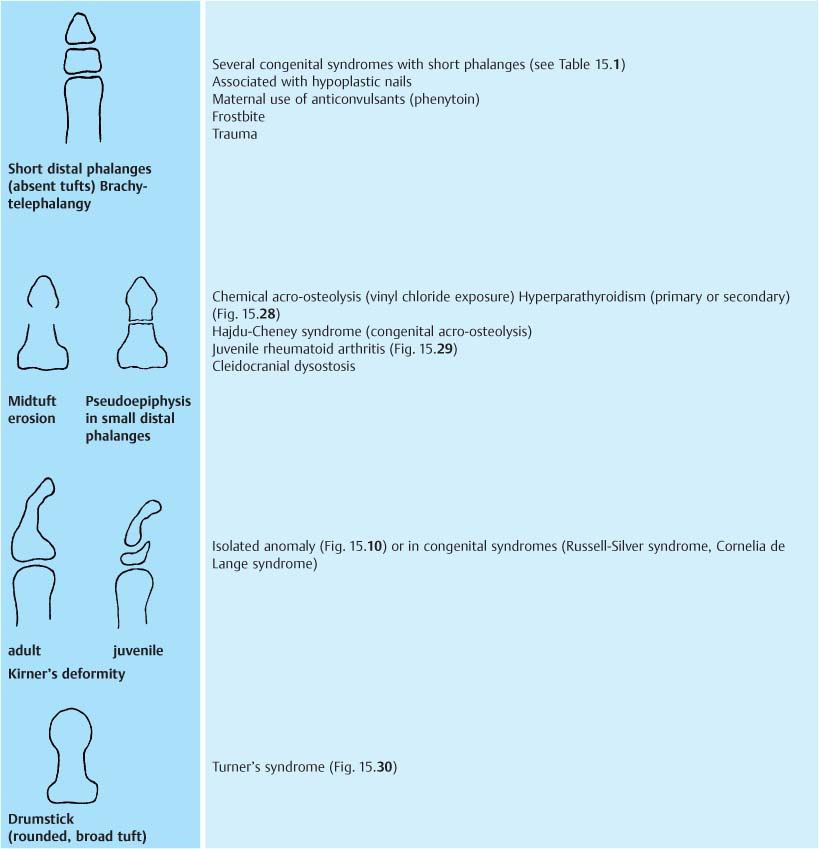

Terminal Phalanx Pattern

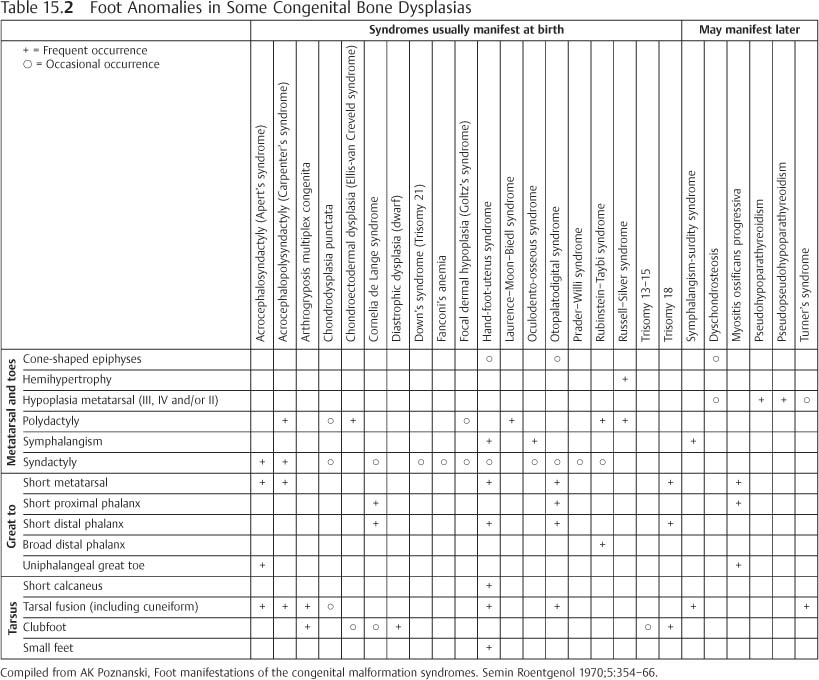

(Revised after SN Jones, DJ Stoker, Radiology at your fingertips: lesions of the terminal phalanx. Clin Radiol 1988;39: 478–85).

The distal ends of the toes are usually poorly delineated in ordinary radiographs, but the distal phalanges of fingers are well visualized. A variety of acquired and congenital diseases, as well as localized lesions, cause changes in the radiographic appearance of the terminal phalanges. The radiographic changes around the distal interphalangeal joints are similar to elsewhere in the skeleton and joints, but the pattern may be different in the terminal tufts. A list of various patterns of distal phalangeal abnormalities with their common or typical causes is presented in Table 15.3.

Fig. 15.15 a, b Otopalatodigital syndrome. a The distal row of carpal bones and the scaphoid are fused. Metacarpal bones 2–4 have narrow diaphyses, while the fifth has an abnormally wide diaphysis but normal length. Finger bones show no gross abnormality. b The foot shows fusion of the navicular with the first cuneiform and of the cuboid with the third cuneiform. The first metatarsal is short relative to the others. The great toe has an abnormal shape (clinodactyly). a b

Fig. 15.16a Subungual exostosis projects characteristically from the distal and dorsomedial aspects of the terminal phalanx of the great toe.

Fig. 15.16b Acromegaly with exaggerated terminal phalangeal tufts, wide metacarpophalangeal joint spaces, increased soft tissue, and premature osteoarthritis.

Fig. 15.17 Acro-osteosclerosis of the distal phalanges. Incidentally, small erosions (arrows) due to early rheumatoid arthritis are also present.

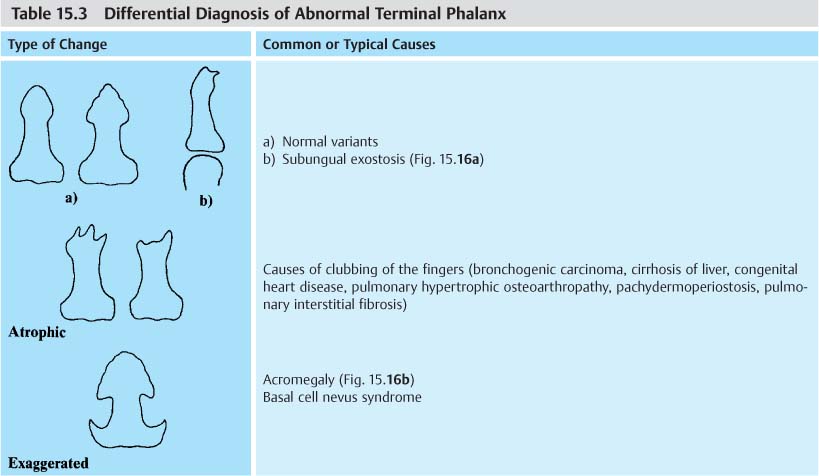

Fig. 15.18 Melorheostosis involving fingers, including terminal phalanges.

Fig. 15.19 Osteopoikilosis with acroosteosclerosis.

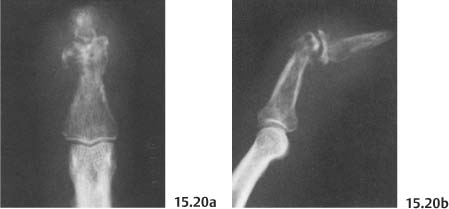

Fig. 15.20 a, b Osteomyelitis with swelling of soft-tissue and destruction of the terminal phalanx.

Fig. 15.21 Metastasis of bronchogenic carcinoma in the distal phalanx. A relatively well-demarcated osteolytic lesion and soft-tissue swelling is seen.

Fig. 15.22 Secondary hyperparathyroidism (renal osteodystrophy). Rarefaction of terminal tufts and subperiosteal erosion in phalanges (arrows).

Fig. 15.23 Psoriatic arthritis. “Morning star” erosion of terminal phalangeal tuft of the 4th finger (arrow).

Fig. 15.24 Hyperparathyroidism. Erosion in the index finger has a “morning star” pattern, but unlike psoriatic arthritis, there is widespread demineralization and subperiosteal erosion elsewhere in the fingers. The other tufts only show rarefaction.

Fig. 15.25 Scleroderma. Acro-osteolysis and soft-tissue atrophy in some fingers (arrows), but no other obvious bone changes.

Fig. 15.26 Frostbite. Localized acro-osteolysis in the great toe with a large soft-tissue ulcer (arrows).

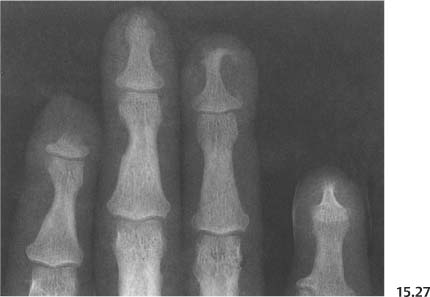

Fig. 15.27 Leprosy. Acro-osteolysis in distal phalanges of the second, fourth and fifth fingers.

Fig. 15.28 Renal osteodystrophy with midtuft erosions and subperiosteal erosions in the phalanges.

Fig. 15.29 Juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Midtuft erosions are seen in the 2nd and 3rd fingers on the right (arrows). There is acro-osteolysis in the left index finger (asterisk).

Fig. 15.30 Tuner’s syndrome. Drumstick tufts and positive metacarpal sign.

Orthopedic Foot Problems

The feet are subject to a number of deformations or painful conditions, not necessarily as a result of the congenital syndromes listed in Tables 15.1 and 15.2.

In the analysis of a deformed foot, one should be aware of a number of important lines and angles of the foot. Some useful lines and angles that should be evaluated from the weight-supporting dorsoplantar and lateral views are presented here (Fig. 15.31).

The midtarsal joint line (A-A) is a continuous line along the anterior margin of the talus and calcaneus on the lateral view and talus and cuboid on the anteroposterior view. A lack of continuity indicates a mobile talus, altered position of the talus and calcaneus relative to the navicular and cuboid at the midtarsal joint, e.g., a midtarsal fault.

The calcaneal pitch (B) is an index of the height of the foot framework; low: 10 to 20 degrees; medium: 20 to 30 degrees; and high, over 30 degrees. Low pitch is indicative of a change in the position of the calcaneus and talus at the ankle joint, e.g., a hindfoot fault as seen in flatfoot.

Böhler’s angle of the calcaneus (C, normal: 20 to 40 degrees) indicates the integrity of the plantar arch of the calcaneus. It is decreased by a calcaneal fracture.

The diagonal axis of the talus (D-D) is a fair indicator of the proper relation of the talus to the calcaneus, normally nearly horizontal. It is not horizontal in most foot deformities.

The talocalcaneal angle in the dorsoplantar view (E) ranges from 20 degrees to 50 degrees in infants and young children and from 15 degrees to 30 degrees from age five on. A line through the axis of the talus points to the head of the first metatarsal bone. The axial line of the calcaneus points to the fourth metatarsal bone. The talocalcaneal angle is increased in flatfoot and is reduced or reversed in clubfoot.

The midtalar and midcalcaneal lines from the lateral view meet near the anterior margin of the cuboid, forming an angle of 25 to 50 degrees (F). The midtalar/midcalcaneal angle is reduced in clubfoot or rockerbottom deformity and increased in flatfoot and pes cavus. The angle formed by lines along the inferior margin of the calcaneus and the fifth metatarsal bone (G) ranges from 150 degrees to 175 degrees and is unaffected by age. The apex of this angle faces downward in flatfoot and rockerbottom deformity.

In order to give a meaningful roentgenographic report on a deformed foot, the radiologist must also know the orthopedic terminology:

1. Valgus (eversion, pronation) = bent outward from the midline of the body, distal to the point or joint of reference

2. Varus (inversion, supination) = bent inward toward midline of the body, distal to the point or joint of the reference

3. Adduction = displacement on a transverse plane toward the axis of the body

4. Abduction = displacement on a transverse plane away from the axis of the body

5. Heel valgus (Fig. 15.32 b) = the outward slant of the heel, as seen from the rear, is increased above 10 degrees (associated with an increased talocalcaneal angle from the dorsoplantar view)

6. Heel varus (Fig. 15.32 c) = the normal valgus angle (5 to 10 degrees) is decreased or the heel slants inward (associated with a decreased talocalcaneal angle in the dorsoplantar view)

7. Equinus = fixed plantar flexion of the hindfoot (anterior end of calcaneus down). From the lateral view, the calcaneus makes an angle of more than 90 degrees anteriorly with the tibia

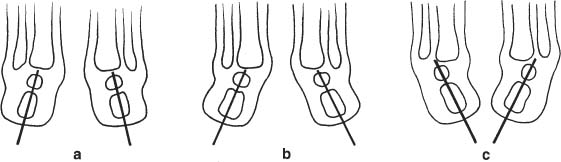

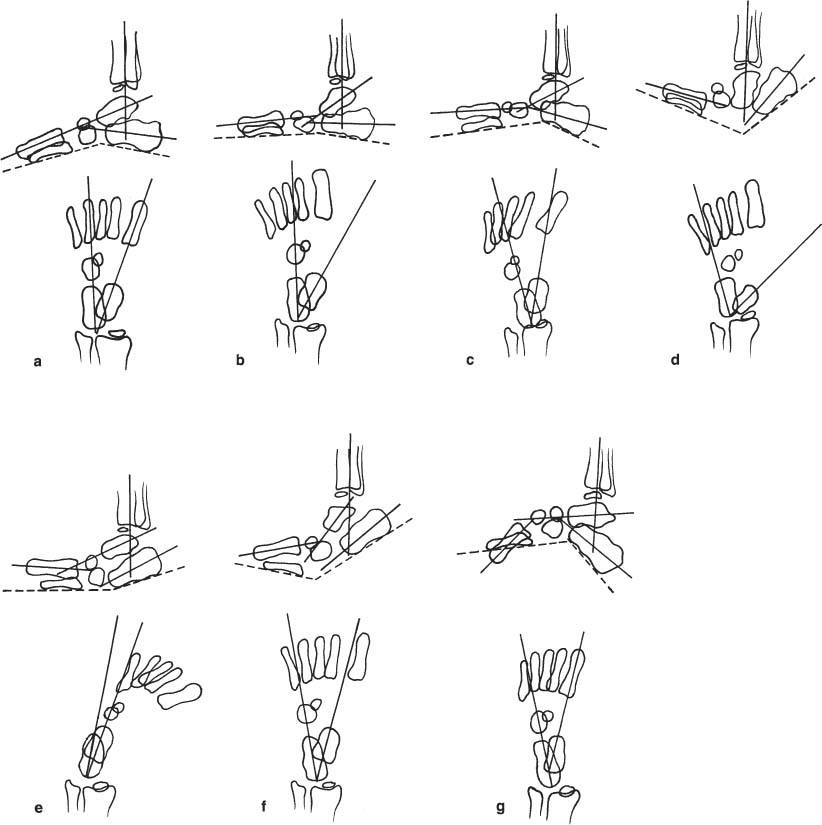

Heel valgus or varus cannot be determined directly from the routine AP and lateral radiographs, but can be inferred from the talocalcaneal angle on the AP view. Table 15.4 lists the more common foot deformities, with their diagnostic and differential diagnostic criteria. The overall appearances of various congenital foot deformities are presented diagrammatically in Fig. 15.33 a–g.

Fig. 15.31 a, b Some useful lines and angles in the evaluation of an orthopedic foot problem. A–A = midtarsal joint line, B = calcaneal pitch, C = Böhler’s angle of the calcaneus. D = diagonal axis of the talus, E = talocalcaneal angle, F = midtalar-midcalcaneal angle, and G = inferior cortex of calcaneus-fifth metatarsal angle.

Fig. 15.32 a–c a Normal heel position (as seen from the rear); b Heel valgus, seen in metatarsus varus (adductus). c Heel varus, seen in club-foot.

Fig. 15.33 a–g The appearance of various congenital foot deformities with special reference to the midtalar-midcalcaneal angle (AP, normally 15°–30°, infants 30°–50° and lateral 25°–50°), the inferior cortex of calcaneus-fifth metatarsal angle (lateral, normally 150°–175°) and the orientation of the metatarsals. a Normal foot, b flatfoot, c metatarsus varus (adductus), d congenital vertical talus (rockerbottom deformity), e clubfoot, f overcorrected clubfoot, and g pes cavus

Table 15.4 Differential Diagnosis of a Deformed Foot

Deformity | Radiographic Characteristics | Comments |

Hallux valgus (hallux abductus valgus) (Figs. 15.34, 15.35) | 1 Abduction of the hallux (angle between the first metatarsal and great toe 10 degrees to 20 degrees = mild; 20 degrees to 30 degrees = moderate; 30 degrees to 45 degrees = severe) with valgus rotation of the hallux. 2 Deviation or subluxation of the metatarsophalangeal joint. 3 Medial prominence and cratering of the medial epicondyle of the first metatarsal head. 4 Adduction of the first metatarsal, intermetatarsal angle (between metatarsal I and II) over 10 degrees. 5 Relative lateral displacement of sesamoid bones. Adduction of the first metatarsal bone may be structural (abnormal metatarsal base called congenital metatarsus Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|