Chapter 2 From Curricular Goals to Instruction

Preparing to Teach

After completing this chapter the reader will be able to:

1. Identify and discuss the characteristics of five different philosophical orientations to curriculum design and give specific examples of how each applies to physical therapy or physical therapist assistant curricula.

2. Describe four broad categories of learning theories that are based on different views of how students can learn: (1) behaviorism, (2) cognitive learning theory, (3) experiential/problem solving, and (4) social-cultural learning theory. Give specific examples of course materials that could best be taught by using each learning theory.

3. Discriminate among three major learning domains (i.e., cognitive, affective, and psychomotor) by citing elementary to complex levels within each that can be used to guide design of course content and assessment of student learning.

4. Identify the four learning styles described by Kolb5 and give examples of student behavior that may be manifested by a high and low interest in each learning style.

5. Discuss construction of and specify the use of three different types of objectives that can be used to guide student learning: (1) behavioral, (2) problem solving, and (3) outcome.

6. Demonstrate how the delivery of course material, design of significant learning experiences, and evaluation of students is linked to the larger concepts of teaching and learning for enduring understanding through the processes of philosophical orientations, learning theories, learning domains, student learning styles, and course objectives.

7. List the items that could be included in a course syllabus.

8. Prepare a syllabus concept map that demonstrates the linkages across course key concepts.

Getting ready to teach a class or a course for the first time is almost always a perplexing situation. Where to start? Educators have suggested there are at least three kinds of knowledge essential to teaching effectively: (1) knowledge of the subject matter, (2) knowledge of the learners, and (3) knowledge of the general principles of teaching (i.e., knowledge of pedagogy).1–4 This chapter presents an overview of the type of knowledge that physical therapy and physical therapist assistant educators are most often missing—knowledge of pedagogy.

Preactive and interactive teaching

In 1967, a yellow paperback book titled, Handbook for Physical Therapy Teachers, was printed and distributed by the American Physical Therapy Association (APTA).6 This small book was developed by a publication committee composed of Ruth Dickinson at Columbia University, Hyman L. Dervitz at Temple University, and Helen Meida at Western Reserve University. This book was the only source of information regarding physical therapy education at the time and included information on how to develop, organize, and teach a physical therapy curriculum across academic and clinical settings. The teaching focus of that pioneering book and this chapter is preactive teaching.

The terms preactive and interactive teaching were coined by psychologist Phillip Jackson.7 Preactive teaching refers to those elements one considers when preparing to teach a course. Such activities include reading background information, preparing course syllabi, developing media, and even arranging the furniture in the classroom. These activities are highly rational—that is, the teacher reads, weighs evidence, reflects, organizes, relates the current class content to past and future classes the students are involved in, and creates an optimal environment for learning. Like the first-year teacher who was grappling with how to organize a 2-hour lecture, most of these activities occur when the teacher is alone and in an environment that allows for quiet, deliberative thought. Preactive preparation allows the teacher time to think through the breadth and depth of information that is to be presented (subject matter knowledge) to a particular group of students (knowledge of learners) as well as the most coherent and understandable way to present the information (pedagogical knowledge).1,2

By contrast, interactive teaching refers to what happens when the teacher is face to face with students. Interactive teaching activities are more or less spontaneous—that is, when working with large groups of students, the teacher tends to do what he or she feels or knows is right. In the chaotic milieu of a classroom, laboratory, or clinic, little time is available to reflect on what are appropriate and useful teaching strategies. Obviously, experienced teachers are considerably more skilled in interactive teaching and reflection-in-action than novice teachers.8 This is similar to experienced clinicians who seem to know the right thing to do with patients with an ease and confidence that amazes novice clinicians. However, thoughtful preactive teaching preparation can allow even the novice teacher the freedom to focus on student understanding and learning rather than remain tightly tied to one’s lecture notes. Preactive teaching elements are covered in this chapter. Chapter 3 focuses on interactive teaching elements.

Preactive teaching grid

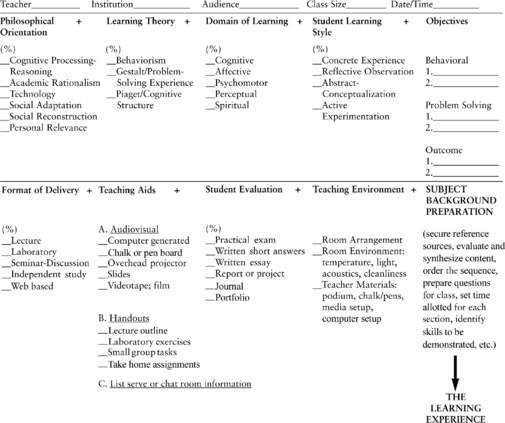

This handbook assumes that the teacher is extraordinarily competent regarding the subject matter to be taught (subject matter knowledge) and is a physical therapist or physical therapist assistant who has a good knowledge of the students to be taught and what information they need for competent clinical practice. However, to organize and present material in a manner that is responsive to the program mission and desired student outcomes, the teacher is urged to think through the components identified in the preactive teaching grid (Figure 2-1). This grid is useful whether designing a whole course or a single class. When all components of the grid have been identified and are related to each other in a coherent fashion, the delivery of the course content also tends to be coherent to student and teacher. Note that the grid encourages the teacher to think through how much percentage in time and effort each of the elements contributes to the presentation of a particular content area.

Philosophical orientation

Eliot Eisner conceived of five philosophical orientations that can be used to guide curriculum design: development of cognitive processes, academic rationalism, technology, societal interests (social adaptation and social reconstruction), and personal relevance.9,10 These orientations are based on what teachers think the aims of a curriculum, course, or class should be—that is, why they are teaching what they are teaching.

Cognitive Processing-Reasoning

Problem-based learning (PBL) is the centerpiece of problem-based curricula. PBL scenarios that are based on key cognitive processes needed by physical therapists are developed by faculty and form the basis of the core curriculum. Students then use “triggers” from the problem case scenario to define their own learning processes and then engage in independent, self-directed study before returning to the group to discuss and build their knowledge base. The building of a knowledge structure or scaffold is an essential component of all learning. Students must build that structure for themselves, and the PBL approach is one that emphasizes a knowledge-building process that is centered on clinical reality. See Table 2-1 for an overview of the steps in a PBL tutorial process.11,12

Table 2-1 Steps in the Problem-based Learning Tutorial Process

| Step | Process |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | Identify and clarify terms in the case scenario that are unfamiliar |

| Step 2 | Define the problem or problems to be discussed (all views should be considered) |

| Step 3 | Discuss the problem(s) at brainstorming sessions Suggest possible explanations based on prior knowledge Students draw on each other’s knowledge; identify areas of incomplete knowledge |

| Step 4 | Review steps 2 and 3; move explanations to tentative solutions; record explanations and restructure if needed |

| Step 5 | Formulate learning objectives; group works toward consensus of learning objectives; tutor makes sure learning objectives are focused, achievable, comprehensive, and appropriate |

| Step 6 | Private study (all students gather information related to each learning objective) |

| Step 7 | Group shares results of private study (students identify their learning resources and share their results); tutor checks learning and assesses group (scribe records key findings during each step of the process) |

Adapted from Cantillon P, Wood D. ABC of Learning and Teaching in Medicine, 2nd ed. West Sussex, UK: Wiley-Blackwell, 2010.

In a problem-based curriculum, the entire curriculum is composed of clinical problems. For example, rather than a class of students sitting in traditional physical therapy courses, such as anatomy, pathology, therapeutic exercise, and health care policy, students in small groups guided by a mentor discuss patient problems. With any given patient problem, students learn to seek out, analyze, and act on the information they need. That is, students gather information from a variety of sources, including anatomy, pathology, therapeutic exercise, and health care economics because these sources relate to the patient problem under consideration. For an excellent overview of the advantages and disadvantages of problem-based learning, read The Challenge of Problem-Based Learning by Boud and Feletti.11

Academic Rationalism

The philosophical orientation of academic rationalism focuses on traditional areas of study that faculty think represent the most intellectually and artistically significant ideas within the field they are teaching. This approach relishes the history and the careful inquiry that have led to formulation of universal principles and philosophical, scientific, and artistic concepts useful in today’s world. In this type of orientation, more time is spent on theory and less on practical application. The belief is that once students learn of the great ideas created by the most visionary people in their field (and related fields), they are able to perform as educated men and women. As Eisner states, “The central aim is to develop man’s rational abilities by introducing his rationality to ideas and objects that represent reason’s highest achievement.”9 Thus, college classes based on the works of great thinkers, such as Darwin, Emily Dickinson, Einstein, Ghandi, Picasso, and Martin Luther King, would have as their focus academic rationalism.

Obviously, no health care curriculum could be based solely on academic rationalism because too much health care information and related patient care intervention strategies are outdated within a decade or less. However, physical therapy and physical therapist assistant educators struggle with how much academic rationalism to put into curriculum. For example, in the neurological rehabilitation area educators may grapple with how many students should be exposed to historical perspectives such as Margaret Rood, Maggie Knott, Berta and Karl Bobath, and Signe Brunnstrom, when compared with the time devoted to the current theories of motor control and motor behavior. In research on stroke rehabilitation, Jette found that therapists now are using more eclectic intervention techniques to address impairments and compensate for functional limitations. Therapists report that their interventions are grounded in motor control and motor learning theories.13

Personal Relevance

The philosophical orientation of personal relevance focuses on what is personally relevant to the student. In this orientation, the teacher and the student jointly plan educational experiences that are meaningful to the student. Probably the archetype of this orientation is portrayed is A. S. Neil’s famous boarding school, Summerhill, founded in England in 1921 and designed to “make the school fit the child instead of making the child fit the school.”14

This orientation is challenging to entry-level physical therapist and physical therapist assistant educators who have little enough time to teach groups of students the basic tenets and tasks of their profession without responding to the individual personal relevance requirements of each student. Although one sees a version of this approach in discussions about addressing generational differences. How are generation X or millennial students different from faculty who are mostly baby boomers, and does this matter in how faculty teach?15 The personal relevance orientation is very much in evidence in continuing education programs as well as post-professional graduate degree programs that must consider adult learners. The most successful continuing education programs appear to be those that offer clinicians knowledge and advanced skills (e.g., in manual therapy), which can be immediately applied in an individual clinician’s health care setting. The most successful post-professional graduate programs appear to be those that offer the student a great deal of latitude in what she or he chooses to pursue and where the faculty is dedicated to encouraging and supporting students in their individual pursuits.

Learning theories

The next column in the upper part of the preactive teaching grid contains learning theories (see Figure 2-1). Theories about how people learn have been discussed at least since the time of the Greek philosopher Plato (428-347 BC). Plato postulated that knowledge was innate—that is, in place at the time of birth. The function of a teacher was to help the learner “recall” what one’s soul had already experienced and learned. Nearly 2000 years after Plato, the British philosopher John Locke (1632-1704) proposed an opposite view of the learner. Locke postulated that infants were born with the mind a blank slate, a tabula rasa. The teacher’s role was to provide experiences that would fill this blank slate with knowledge.16

There are many ways to classify learning theories. We use four broad categories (Table 2-2)16–19:

Table 2-2 Common Categories of Learning Theories

| Learning Theory | Key Concepts | Examples of Application |

|---|---|---|

| Behavioral learning theory | Based on the concept that behavior could be influenced by the consequences (that reinforcement could help shape the desired behavior) Useful for teaching skills with measurable actions Foundation for performance-based education Some behavioral checklists may be inadequate for some professional competencies | Mastery learning, where you have the opportunity to practice the behavior and receive feedback on performance until mastery is achieved Often used for teaching technical patient care skills Can be used for assessing clinical competencies (particularly skills) |

| Cognitive learning theory | Emerged when limitations of behavioral theory were discovered Learning is an active process of meaning making whereby the organization or structure of knowledge is a critical element Addresses the use, such as information processing and retrieval and transfer of knowledge into practice settings | Foundation for building knowledge in the learner’s memory Knowledge that is connected to a clinical context bolsters retention Building a strong knowledge structure is necessary for developing reasoning and clinical judgment skills |

| Experiential/problem-solving learning theory | Experience and reflection on that experience are central to learning Students must learn not only what but also how to apply what they know Reflection-in-action is necessary for building practice-based knowledge | Designing learning opportunities whereby learners are engaged in active learning Creating learning experiences in which there is a structure that facilitates learner reflection on the learning Experiential learning is well suited to clinical or community settings |

| Social-cultural learning theory | Learning occurs in the social or practice setting The learning is situated in the community of practice as the learner engages in participation with others Meanings are socially constructed in these communities of practice | Clinical practice settings are powerful examples of social-cultural learning The social learning community needs to build self-efficacy in learners to allow them to have incremental success and enhanced participation Role models and mentors can have a powerful effect on the learners |

Behavioral Learning Theories

The behaviorism theory was developed in the first half of the 20th century as a result of numerous experiments, primarily on animals and birds, by the experimental psychologists E. L. Thorndike20 and B. F. Skinner.21 The basic theory of behaviorism rests on their observations that behaviors that were rewarded (positively reinforced) would reoccur. For behaviorists, the process of learning involves rewarding correct behavior until the behavioral change is consistently demonstrated.16,17

Physical therapists and physical therapist assistants use behavioristic principles continually in patient care to teach psychomotor skills. For example, patients are reinforced with enthusiastic praise for attempting and subsequently achieving self-care activities or gait training. In classrooms, acquiring accurate knowledge (i.e., knowing the right answer) is rewarded by receiving high grades and praise from faculty. Lack of responsiveness to acquiring the knowledge presented is quelled by poor grades and perhaps even failure to proceed in the program. Computer-assisted instruction is based almost exclusively on this learning theory. Students receive immediate feedback contingent on the accuracy of their responses. Clearly, many psychomotor skills and specific facts that need to be memorized are successfully taught using behavioristic principles. For a teacher whose main philosophical orientation to a course is technology, the predominant learning theory of choice would be behaviorism. The behavioral approach works well when teaching a skill with a measurable action.17,18

Cognitive Learning Theories

Cognitive learning theory focuses on the development of knowledge structures, abstract problem presentation, and problem solving that are critical elements of clinical reasoning. Cognitive learning theory development stemmed from the perceived inadequacy of stimulus-response behavioral theories of learning that did not account for advanced knowledge and skill development that is so critical in professional education.17,18 Jean Piaget’s well-known research demonstrating the influence of the environment on the cognitive development of children and the stages of the learner as he or she is developing cognitive schema.22,23 Building on the work of early theorists, Ausubel24 asserted that learners construct meaningful knowledge by being able to connect new concepts or knowledge to what they already know.24 Learners need to build that structure, not just have information poured in.

Robert Gagne proposes a hierarchy of learning that begins with the simple and concrete and moves to the complex and abstract.25 The ideas contained within stages of a hierarchy suggest that higher-order cognitive abilities build on lower-order cognitive abilities. That is, students must master lower-order abilities before they can master higher-level ones. Gagne suggests the following hierarchy: (1) facts, (2) concepts, (3) principles, and (4) problem solving. Thus, for example, students should be able to identify the muscles, nerves, and connective tissues involved in the shoulder rotator cuff (facts) before they can understand conceptually how these structures fit together. After they understand how the structures are related, they can understand the biomechanical principles involved in the rotator cuff mechanism. After understanding these principles, they can solve problems related to rotator cuff injuries. If a student missed any one of these steps, it would be difficult to proceed to the next step. For example, if the student did not understand conceptually how the various tissue structures are related, then it would be difficult to understand the biomechanics of movement. Thus, cognitive structure learning theories are very useful in thinking about ways to organize and present information. For a teacher whose main philosophical orientation to a course is academic rationalism, the predominant learning theory of choice would be cognitive learning theories.

Albert Bandura’s work in social learning theory and more recently social-cognitive learning theory has led to the development of several models and frameworks for understanding the underlying values and beliefs that are part of health behaviors and facilitating behavior change.26 Much of this work is focused on applied behavioral theory and adherence (see Chapter 13).

Experiential/Problem-Solving Learning Theories

John Dewey (1859-1952), who has been called America’s greatest educational philosopher, expanded on the experiential learning theory or learning through context and experience.17 For Dewey, the issue of activity (i.e., students being actively involved in an authentic experience from which they could learn) was essential.27

This principle of learning through experience clearly operates in clinical practice and academic settings. Physical therapists, who in the past prepared patients for functional activities by working on strength and endurance of specific muscle groups, now ascribe to modern motor learning theories in which teaching movement within meaningful functional patterns hastens the acquisition of motor skills (see Chapter 14). In academic settings, it is known that students need a framework for information so that the knowledge “makes sense.” For example, the tedious process of memorizing anatomic origins and insertions of muscle groups in an anatomy class has long been seen as an absolute necessity to the practice of physical therapy. However, students are quick to point out that learning this anatomic information is greatly enhanced by acquiring corresponding knowledge of the function of muscle groups in a kinesiology class and learning how to assist patients to improve the function of muscle groups in a therapeutic exercise class. In this manner, students learn and understand the origin and insertion of muscle groups in the context of muscle function and in the context of the use of this information in patient care. Thus, memorization of anatomic structures is easier because it has a useful experiential context and therefore “makes sense.”

Dewey described the process of human problem solving, reflective thinking, and learning in many slightly different ways because he knew that intelligent thinking and learning is not just following some standard recipe. He believed that intelligence is creative and flexible—we learn from engaging ourselves in a variety of experiences in the world. However, in all of his descriptions, the following elements always appeared in some form: Thinking always gets started when a person genuinely feels a problem arise. Then the mind actively jumps back and forth—struggling to find a clearer formulation of the problem, looking for suggestions for possible solutions, surveying elements in the problematic situation that might be relevant, drawing on prior knowledge in an attempt to better understand the situation. Then the mind begins forming a plan of action, a hypothesis about how best the problem might be solved. The hypothesis is then tested; if the problem is solved, then according to Dewey something has been learned.17–19

Both in the classroom and in the clinic, when teachers present students with clinical problems to solve, they are following the traditions of John Dewey. Perhaps even more important, Dewey illuminates how we learn from our experience in clinical practice. His postulation that learning occurs from actively solving meaningful problems explains the accumulated wisdom of experienced practitioners that is far beyond the knowledge contained in current textbooks. The concepts of reflection-in-action and reflection-on-action described by Donald Schön and elaborated on in Chapter 3 of this book are the present-day versions of this experiential learning theory that was first articulated by Dewey.8 For a teacher whose main philosophical orientation to a course is development of cognitive processing-reasoning, the predominant learning theory of choice would be the experiential.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree