Chapter 82 Fractures of the Patella

Patellar fractures constitute approximately 1% of all bony injuries, with traffic accidents and falls being the most common causes.16 Fractures have also been associated with excessive extensor mechanism contraction, total knee arthroplasty, post–anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstruction, postsurgical stabilization, chronic disease (e.g., gout), and severe squatting with weight lifting. Because of its subcutaneous location and the significant joint reactive forces to which it is subjected, the patella is prone to injury.2,52,66,74,100 Post-traumatic complications include knee stiffness, extensor mechanism weakness, and symptomatic arthritis. Compared with other orthopedic injuries, a paucity of literature on treatment is available along with a limited consensus on which treatment options are best. Even so, the goals of treatment remain constant: reconstitution of the extensor mechanism and restoration of articular congruity.

Anatomy

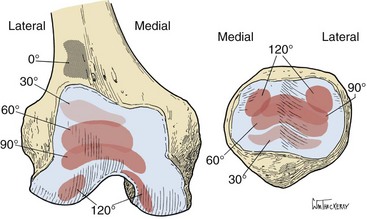

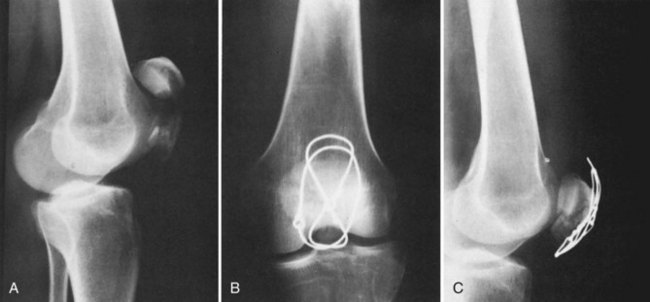

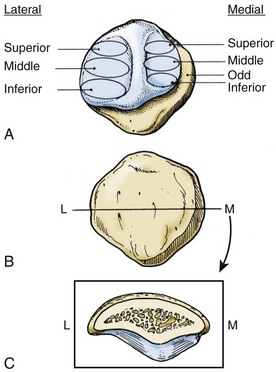

The patella lies deep to the fascia lata and tendinous rectus femoris, making it the largest sesamoid bone in the body.84 Its distal-most aspect is termed the apex, and its proximal end is known as the basis.84 Seven facets are separated by a major and minor vertical ridge, and two transverse ridges traverse the major vertical ridge84 (Fig. 82-1).

Figure 82-1 A, The seven patellar facets. B, The anterior surface. C, Cross-section of a Wiberg II patella.

(From Scuderi G: The patella, New York, 1995, Springer-Verlag.)

The ossification center of the patella most commonly presents between 3 and 5 years of age. As this center enlarges, it may be associated with multiple accessory ossification centers, most commonly superolateral—the bipartite patella.77 These accessory ossification centers usually have a nonossified cartilaginous connection to the central ossification center.

The Wiberg classification and the Baumgartl modification have been used to classify the patella. Type I has equal medial and lateral facets, and progressive types have smaller medial facets finally leading to no medial facet, also known as the Jaegerhut patella.7,111 Proximally, the undersurface of the patella is covered with the thickest articular cartilage in the body, and the distal 25% is devoid of articular cartilage.29

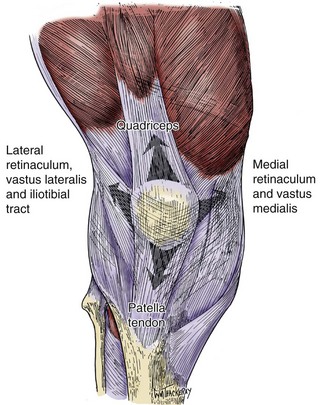

The four muscles of the extensor mechanism (rectus femoris, vastus medialis, vastus lateralis, and vastus intermedius), the fascia lata, the patellar tendon, and the retinaculum of the knee all attach to the patella (Fig. 82-2). The rectus femoris is most superficial and central, with its fibers running approximately 7 to 10 degrees medial relative to the femur. The vastus medialis has two portions (longus—proximal attachment to patella, obliquus—distal attachment to patella) that attach to the patella at angles of approximately 15 and 50 degrees, respectively. The vastus lateralis attaches proximally on the patella at an angle of approximately 30 degrees. Laterally, it fuses with the iliotibial band and the lateral retinaculum. The vastus intermedius is the deepest portion of the quadriceps, attaching directly superiorly into the patella. The retinaculum of the knee is composed of the overlying fascia lata anteriorly, which blends with the vastus medialis and lateralis, as well as with the capsule. The patellar tendon is the terminal soft tissue extension of the extensor mechanism that inserts into the tibial tubercle. It is approximately 5 cm long and is formed by central fibers of the rectus femoris, fascial expansions of the iliotibial band, and the patellar retinaculum.16,59,84 Thickenings of the capsule connect the patella to the femoral epicondyles and aid in appropriate tracking, with the medial patellofemoral ligament contributing 53% to the lateral stability of the patella.28

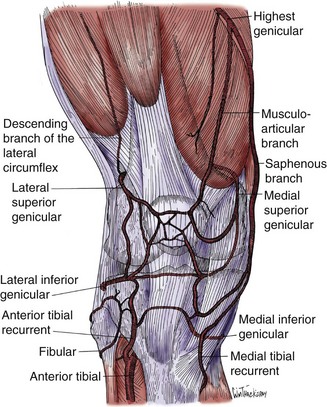

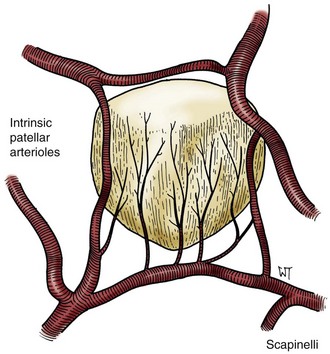

The blood supply of the patella is composed of the peripatellar plexus, which is derived from six separate arteries (Fig. 82-3). The supreme geniculate artery is derived from the superficial femoral artery at the adductor canal. The four geniculate arteries (superolateral, superomedial, inferolateral, and inferomedial arteries) are derived from the popliteal artery. Finally, the recurrent anterior tibial artery is derived from a branch of the anterior tibial artery at the interosseous membrane.6,89 The net functional blood supply of the patella moves in a distal-to-proximal direction96 (Fig. 82-4).

Biomechanics

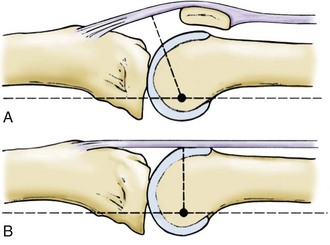

From full flexion to 45 degrees, the load is shared between the patella and the tendinous portion of the extensor mechanism. At less than 45 degrees of flexion, the only component of the extensor mechanism in contact with the distal femur is the patella. The patella causes an increase in the moment arm of the extensor mechanism by displacing it anteriorly from the knee’s center of rotation (Fig. 82-5). This increases the force of the extensor mechanism by up to 50%. The terminal 15 degrees of extension require twice the torque required to extend the knee from full flexion to 15 degrees.51,59 Thus, the patella functions as a pulley. With total patellectomy, numerous studies have documented up to a 50% decrease in isokinetic strength testing of the extensor mechanism.82,102,108

Because of the small area of contact at the patellofemoral articulation, the undersurface of the patella is subjected to some of the highest joint reactive forces in the body—up to 7.6 times body weight—even though overall tibiofemoral forces are greater.40,85

At any point within the knee’s range of motion, a maximum of 13% to 38% of contact of the patella occurs with the femur.65 Throughout flexion, the area of patellofemoral contact changes. At 20 degrees of flexion, the patella centers within the trochlear groove. As greater angles of flexion are achieved, the area of contact moves proximally on the patella’s undersurface and distally on the trochlea36 (Fig. 82-6).

Diagnosis

History and Physical Examination

Usually the patient will describe a fall or a direct blow to the anterior knee that represents direct force. Indirect force may be represented by a severe eccentric contraction resulting in a transverse patellar fracture. This may occur in the flexed knee with severe quadriceps contraction that literally results in transverse tearing of the patella and the retinaculum. Historically, classification systems involved stratifying injury patterns according to mechanisms.6,15,16 Frequently, injuries represent a combination of direct and indirect forces.

The patient often presents with pain, a large effusion, inability to walk, and inability to straight-leg raise or extend the bent knee. It is important to examine for other associated injuries that may be present in high-energy trauma. Also, the quality of the surrounding soft tissues is important when any patient with an orthopedic injury is evaluated and treated. If traumatic arthrotomy or open patellar fracture is suspected, diagnostic injection may facilitate making the diagnosis. Also, sterile local anesthetic injection following needle aspiration of hematoma may allow for more accurate physical examination. A persistent inability to actively extend the knee implies concomitant injury to the medial and lateral quadriceps expansions.16,94

Diagnostic Studies

The AP view should reveal the position of the patella relative to the femoral sulcus and the relation of the distal pole of the patella to the distal femoral condyles. At times, the presence of an accessory ossification center (e.g., bipartite patella) may be confused for a fracture. Frequently, bipartite patellae are bilateral and are found at the superolateral aspect of the patella. Usually, a bipartite patella is asymptomatic and does not affect extensor mechanism function. Contralateral radiographs may be useful in confirming this diagnosis.68 Unilateral bipartite patellae are rare and often represent an old marginal patellar fracture.30 Recent reports in the literature have documented cases of painful bipartite patella after injury. These have been treated nonoperatively, with excision, or with lateral release.22,46,71,78

Lateral radiographs help define displacement and articular step-off with patellar fractures. Also, avulsion fractures of the tibial tubercle can be identified. These views should be acquired with 30 degrees of knee flexion to allow calculation of the height of the patella relative to the long bones of the knee. The Insall-Salvati ratio, that is, the length of the patellar tendon to the length of the patella (distal pole should be at a level tangential to Blumensaat’s line—distal physeal scar remnant) can be calculated. Approximately 1.0 is normal, >1.2 indicates patella alta, and <0.8 indicates patella baja.44,48,86 This method has been criticized because patellar shape is known to be variable—a fact that may influence classification of patellar height.38,48 Alternatively, the Blackburne-Peel index (ratio of the distance from the tibial plateau to the inferior articular surface of the patella to the length of the patella articular surface) can be calculated. Normally, this is approximately 0.8, with a value >1.0 indicating patella alta.11,12,93

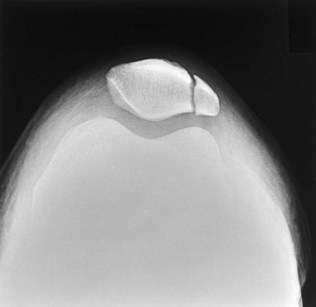

The tangential view (Merchant view) is taken with the patient supine and with passive positioning of the limb at 45 degrees of flexion.70 This view may help define vertical fractures, osteochondral fractures, and marginal fractures (Fig. 82-7).

Computed tomography (CT) has been used to identify stress fractures, especially in patients with osteopenia and hemarthrosis.4 CT scans have been shown to have a 71% detection rate of these fractures as opposed to a 30% detection rate with bone scans in the setting of negative plain radiographs.4 With patellar pathology, bone scans ± indium-labeled leukocytes or gallium scanning may be helpful in evaluating patellar osteomyelitis, tumors, and ischemia.1,32,34,49 CT scans may also be used to evaluate cases of nonunion and malunion, as well as patellofemoral alignment disorders.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has been used in evaluation of quadriceps tendon injury, patellar tendon injury, and post patellar dislocation. With tendon rupture, the normal low-intensity signal of the tendon will be interrupted and the tendon edges obscured.113 Even after relocation of a dislocated patella, a set of concomitant injuries is often present (e.g., contusion of the lateral femoral condyle, tear of the medial retinaculum, and a joint effusion).107

Classification

No specific classification system has proved effective in determining outcomes based on degree of displacement, fracture pattern, or proposed mechanism of injury. Therefore, long-term results most commonly have been associated with the type of treatment.* Reasons for selecting operative treatment have included fractures with a ≥3-mm fracture gap, ≥2 mm articular incongruity, and extensor mechanism dysfunction.15,16,68,94

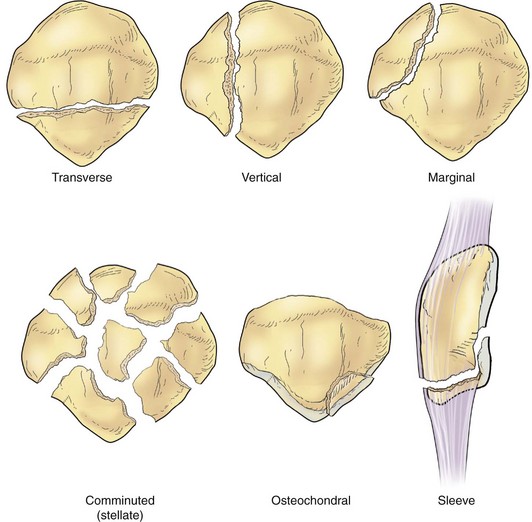

Evaluation of a fracture according to its pattern (transverse, vertical, stellate, apical, marginal, osteochondral), the patient’s functional capacity, and the surrounding soft tissue envelope provides the surgeon with the most helpful information when choosing appropriate treatment (Fig. 82-8).

Nonoperative Treatment

Typically, nonoperative treatment involves application of well-padded immobilization (cast, splint, knee immobilizer) in nearly full extension for 4 to 6 weeks. Weight bearing as tolerated is permitted, and isometric quadriceps exercises along with straight-leg raises are begun within 1 week of injury.16,18,39 When consolidation is evident on follow-up radiographs, active range-of-motion exercises are encouraged.

Historically, nonoperative treatment has yielded 90% good to excellent results, with only 1% of treatments leading to a poor result.16 A more modern series reviewing nonoperative treatment of 40 patellar fractures revealed that 80% of patients were pain free and 90% had full knee range of motion at an average follow-up of 30.5 months.18 The importance of timely, controlled physical therapy is imperative for avoiding arthrofibrosis and patella infera.63 One case report describes patella infera following nonoperative treatment; a tibial tubercle osteotomy was required that yielded only partial correction and resulted in symptomatic recurrence.72

Operative Treatment

Operative intervention has been indicated in patellar fractures that are open, with a ≥3-mm fracture gap, ≥2 mm articular incongruity, or extensor mechanism dysfunction.15,16,68,94,104 The goals are to provide adequate reduction with stable fixation while preserving a viable soft tissue envelope to allow early rehabilitation and uneventful healing.

Alternatively, a transverse incision can be used in cases of transverse fracture to allow limited soft tissue stripping and to obtain a cosmetically pleasing result.6,73 Before this approach is chosen, careful consideration must be given to the potential for subsequent procedures.

In young patients with severely comminuted fractures and good bone quality with an intact soft tissue envelope, extensile exposure through a tibial tubercle osteotomy has been described. After a midline longitudinal incision through skin and subcutaneous tissue, a lateral parapatellar incision is made. The tibial tubercle is predrilled and tapped for eventual large fragment screw fixation. Then it is osteotomized 1.5 cm deep to a healthy bed of dense cancellous bone.9 Six patients with an average of 31 months’ follow-up had four good results, one fair, and one poor with this technique. Clinical union of the osteotomy occurred at an average of 8 weeks, and clinical union of the patella was noted at an average of 11 weeks.9

Internal Fixation

Original wiring techniques used circumferential cerclage wires, or wires passed through drill holes were used; this was followed by 4 to 6 weeks of cast immobilization. These techniques did not incorporate tension band principles. Results were often suboptimal as noted in the inability to start early motion, lack of articular compression, and lack of stable fixation.13,16,92

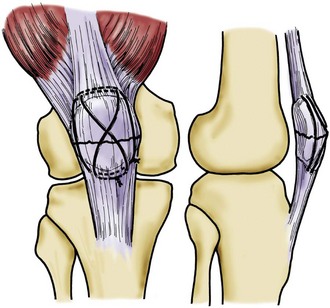

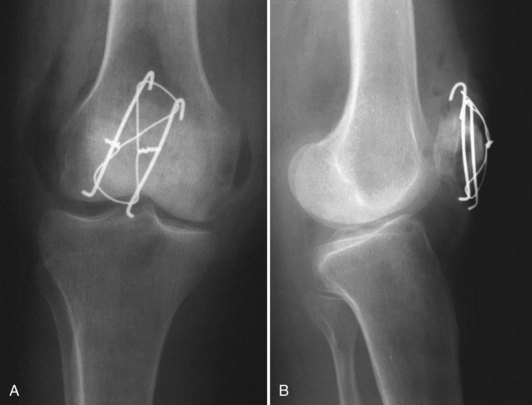

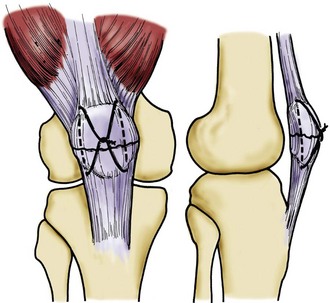

In the 1950s, the tension band concept was popularized by the Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Osteosynthesefragen/Association for the Study of Internal Fixation (AO/ASIF) group. Two 18-gauge stainless steel wires are used. One is placed through the quadriceps and patellar tendons in a figure-of-eight configuration anterior to the patella; the other is placed in a cerclage fashion around the patella.73 Weber showed that these techniques yielded improved results and were stable enough to allow early range of motion.110 Modifications to this technique have evolved. The addition of two parallel longitudinal Kirschner wires placed through the patella can prevent toggling of fragments (Figs. 82-9 and 82-10). The Kirschner wires may be placed retrograde through the transverse component of the main proximal and distal fragments and then advanced antegrade once reduction has been attained. The proximal ends of the Kirschner wires are bent into a “hook” that is bent over the tension band wire into the proximal pole of the patella. To be effective, the figure-of-eight tension band wire must be free of slack and must come in contact with the posterior aspect of the Kirschner wires and the bone, both proximally and distally (Fig. 82-11A and B).

Horizontal wiring versus standard vertical wiring in tension banding has been evaluated biomechanically. With this method, K-wires are inserted in standard fashion, but the 8 created by the wire around the K-wires lies horizontally versus its classical vertical position. In biomechanical testing, permanent fracture displacement was 67% lower with a horizontal orientation than with the standard vertical orientation.47

Lotke and associates described a modified technique for transverse patellar fractures called longitudinal anterior band plus cerclage wiring (LABC). Two vertical holes separated by a 1-cm bone bridge are drilled longitudinally with a Beath-Steinmann pin through the reduced patella. A single wire is threaded on the pins and drawn through the patella. The midportion of the wire is folded over the anterior surface of the patella, while one end of the wire is passed through this loop and tied. If necessary, a supplementary cerclage wire can be added6 (Figs. 82-12 and 82-13A and B). In the original series of 16 patients, 13 were asymptomatic, and 3 noted some discomfort with stairs or prolonged activity. All patients had ≥90 degrees of motion within 6 weeks of the procedure.6

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree