Chapter 19 Fractures of the Distal Humerus

Total Elbow Arthroplasty

Introduction

The goal for an elderly patient with a complex distal humerus fracture is to regain a painless, stable and functional elbow joint, in order to undertake activities of daily living and maintain independence. However, the management of these injuries is difficult and often complicated by poor bone quality and less than ideal soft tissues.1,2 When internal fixation is undertaken, approximately 2–10% of patients develop a non-union of their distal humeral fracture with the associated problems of failed metalwork.3 In 1997, total elbow arthroplasty (TEA) was presented as a therapeutic alternative to open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) in elderly patients.4 Since that time several studies have been published that help to define the ideal patient for a TEA and to predict the results that can be expected.

Presentation, investigation and treatment options

Alternatives to TEA

Functional treatment of distal humeral fractures gives inconstant results and patients often have persistent pain, stiffness, or instability. While these ‘limited treatment goals’ may be acceptable for debilitated patients, Lecestre et al5 found that with this therapeutic option satisfactory results were obtained in less than 40% of cases.

Lecestre et al5 have shown that following internal fixation of comminuted articular fractures satisfactory results can be expected in only 61% of cases. Bonnevialle and Ferron in 20026 reported a 25% loss of upper limb function in elderly patients following distal humeral fractures. Kocher et al7 reviewed 169 patients treated surgically for distal humeral fractures, 32 of whom were more than 65 years old (average age 78 years). Satisfactory results were obtained in only 75%.

In a meta-analysis Helfet and Schmeling8 found 25% unsatisfactory results, while John et al9 in a review of 49 patients older than 75 years noted 20% unsatisfactory results. One-third of the patients in this study had persistent pain. Pereles et al10 showed that only 25% of their patients were pain free. More recently, Pajarinen and Bjorkenheim11 found older age and poor bone quality to be determinant prognostic factors for unsatisfactory results.

Srinivasan et al12 reported their experience of ORIF in 21 patients with a mean age of 85 years (range 75–100 years) and identified fair or poor outcomes in 43%. Proust et al13 in 2007 reviewed 34 patients (36 fractures) with an average age of 78 years who had sustained AO type C fractures treated surgically with ORIF. At 35 months average follow-up, only 58% of the patients had satisfactory results. The average range of motion in extension/flexion was 38–116°. A high complication rate of 56% was noted, with nine non-unions and four mechanical failures.

Surgical techniques and rehabilitation14,15

The patient is positioned supine on the operating table and the involved arm placed over a bolster and across the chest (Fig. 19.1). A straight 18 cm posterior skin incision is centred just lateral to the tip of the olecranon (Fig. 19.2).

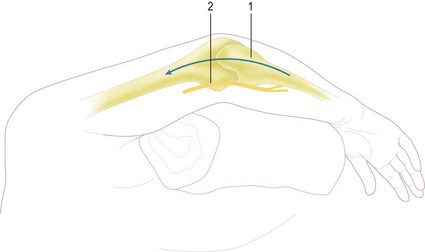

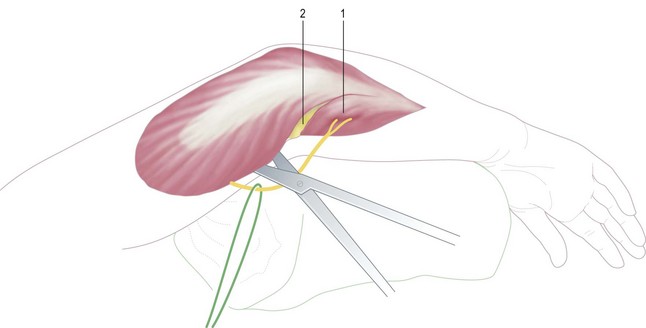

The ulnar nerve is identified, released from the medial epicondyle and exposed to its first motor branch (Fig. 19.3). The extensor mechanism is then detached from the olecranon in continuity, from medial to lateral allowing dislocation of the elbow (Fig. 19.4). Alternatively, the triceps can be left attached on the olecranon and the fracture fragments removed by releasing all soft tissue attachments, including the capsule.

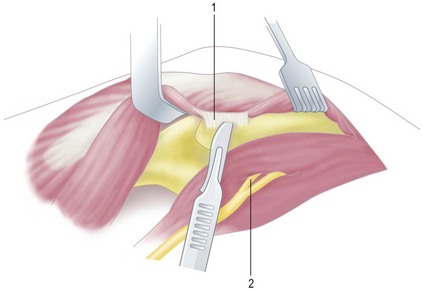

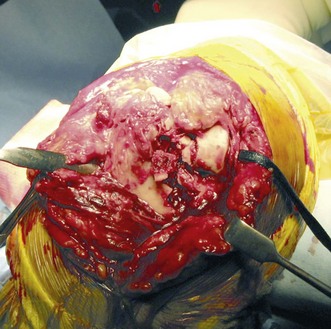

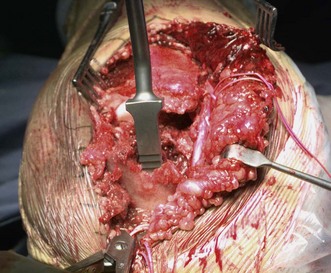

The humeral preparation is straightforward. The fractured fragments are removed (Fig. 19.5), and the canal prepared using the humeral reamers (Fig. 19.6). The depth of insertion of the humeral component is defined by the flange of the implant resting on the roof of the coronoid fossa.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree