Fig. 12.1

Approach to the ulna. The skin incision is performed 5-mm volar or dorsal of the palpable edge of the ulna on a line between the olecranon and styloid process of the ulna. Between m. extensor and flexor carpi ulnaris a direct approach is made to the bone. Proximally, the anconeus m. must be detached. Care must be taken with the dorsalis manus branch of the ulnar nerve

The skin incision is on a line between the olecranon and ulnar styloid process. The incision falls in the plane between the medial and lateral posterior cutaneous nerves of the forearm. The dorsal cutaneous branch of the ulnar nerve crosses the extreme distal end of the ulna, running from volar to dorsal, and care must be taken to avoid injuring its branches. The posterior apex of the ulnar shaft defines the plane between the extensor carpi ulnaris innervated by radial nerve and the flexor carpi ulnaris innervated by ulnar nerve. Proximally, the ulna is exposed by detaching the anconeus. The ulnar nerve and artery lie underneath the flexor carpi ulnaris on top of the flexor digitorum profundus and are easily avoided, provided that elevation of the flexor carpi ulnaris is performed close to the bone and does not stray into its substance [2].

12.4.2 Radius

12.4.2.1 Thompson Approach (Fig. 12.2a–d)

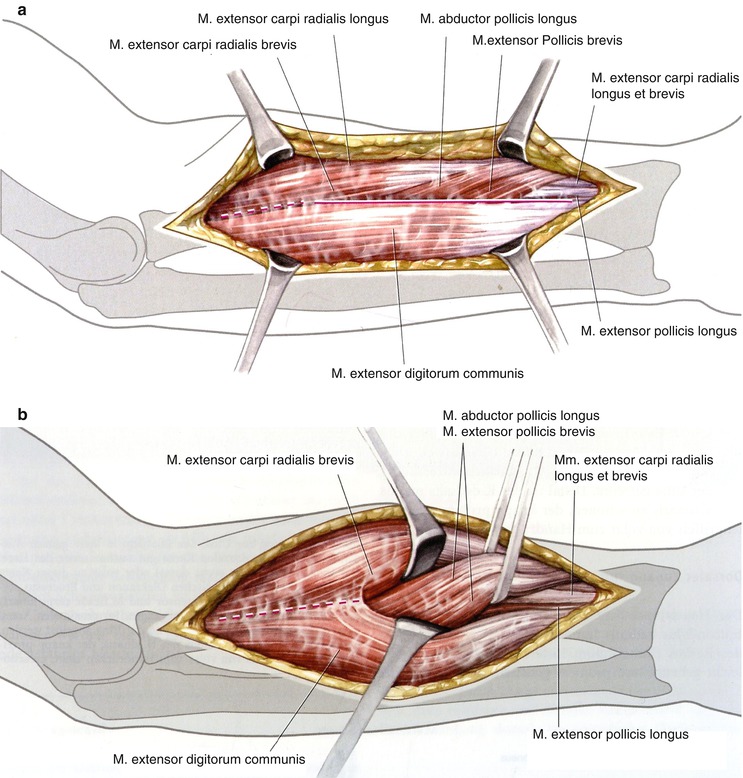

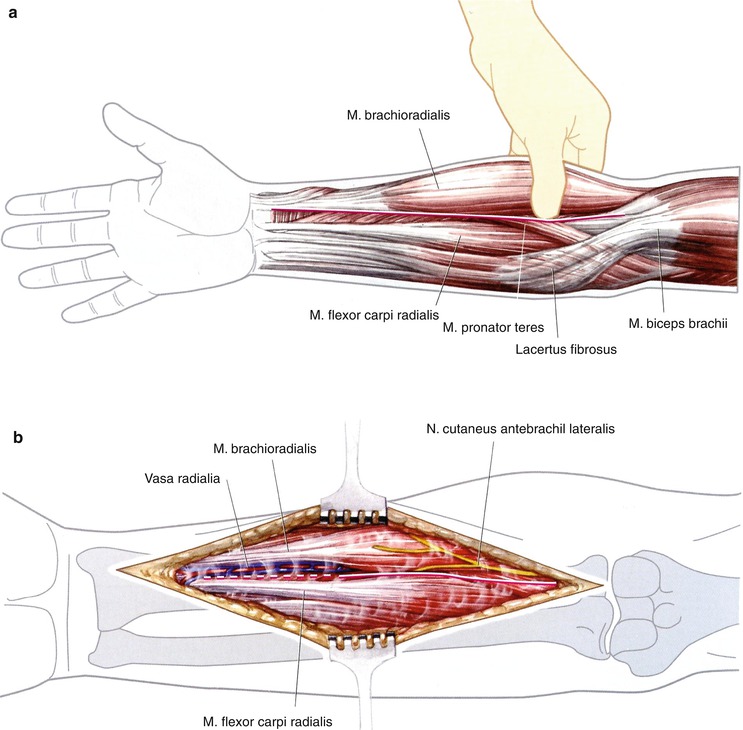

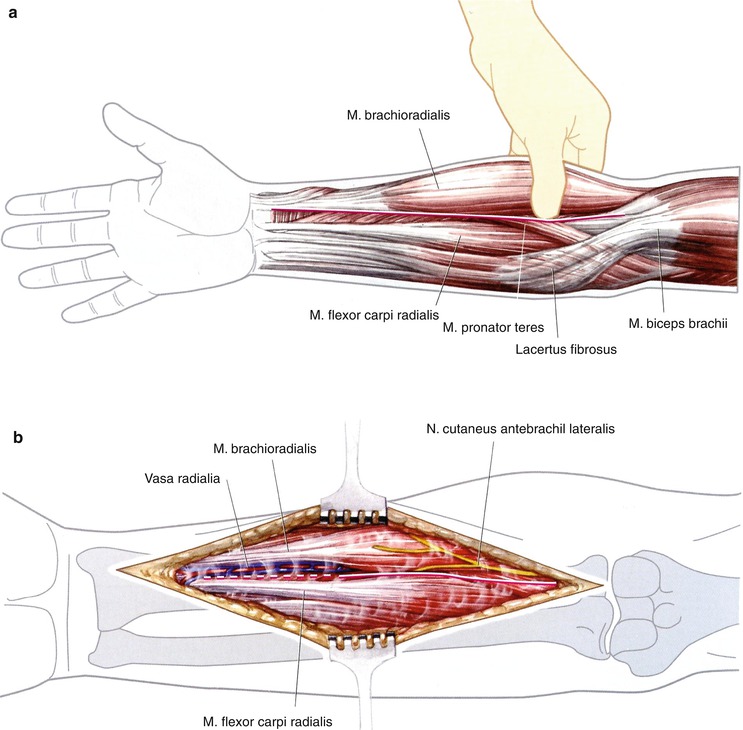

Fig. 12.2

Dorsal approach to the mid- and dorsal part of the radius. The skin incision is on a line between the radial epicondyle and Lister’s tubercle. Incision of the fascia is made on the radial border of the extensor digitorum communis muscle and between this muscle and the extensor carpi radialis brevis muscle in the direct approach to the radius (a). Under distraction of both these muscles, awareness of the abductor pollicis longus and the extensor pollicis brevis muscle is required. The fascia is incised at the proximal and distal border. Both muscles are mobilized and tied with a loop (b). For proximal fractures, the supinator m. Must be identified (c). Three transverse fingers away from the radial head, the radial nerve can be felt, which is prepared by splitting of the supinator m (d)

The radial shaft can be exposed through either a dorsal or volar approach. The dorsal approach is commonly referred to by the eponym Thompson, the surgeon who popularized the approach [2].

The skin incision is a line between the lateral epicondyle and dorsal middle of the radius (Lister’s tubercle). The elbow is slightly flexed and pronated. The fascia is divided at the radial border of extensor digitorum communis and further preparation is in the interval between this muscle and the extensor carpi radialis brevis. Distally, the abductor pollicis longus and extensor pollicis brevis emerge from between the mobile wad and dorsal compartment musculature in the distal half of the forearm. The fascia are incised at the proximal and distal border of these muscles. The bone is exposed by mobilization and retraction of both crossing muscles. The exposure of the proximal part of the radius requires identification and mobilization of the posterior interosseous nerve, as this nerve may lie almost adjacent to the bone at this level and could potentially be trapped beneath the plate. The posterior interosseous nerve emerges from beneath the superficial and deep heads of the supinator muscle, approximately 1 cm proximal to the distal limit of this muscle. It can be identified at this point and then dissected free from the muscle, preserving its muscular branches. After sufficient proximal mobilization of the nerve, exposure of the radial shaft can be performed by rotating the radius into full supination and detaching the insertion of the supinator from the anterior aspect of the radius [2].

12.4.3 Anterior or Henry Exposure

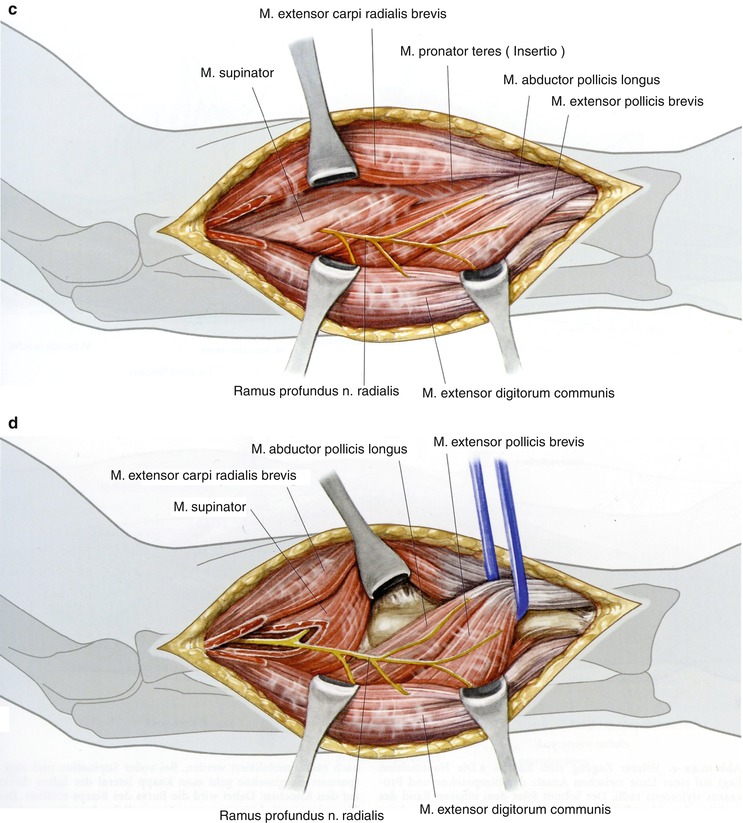

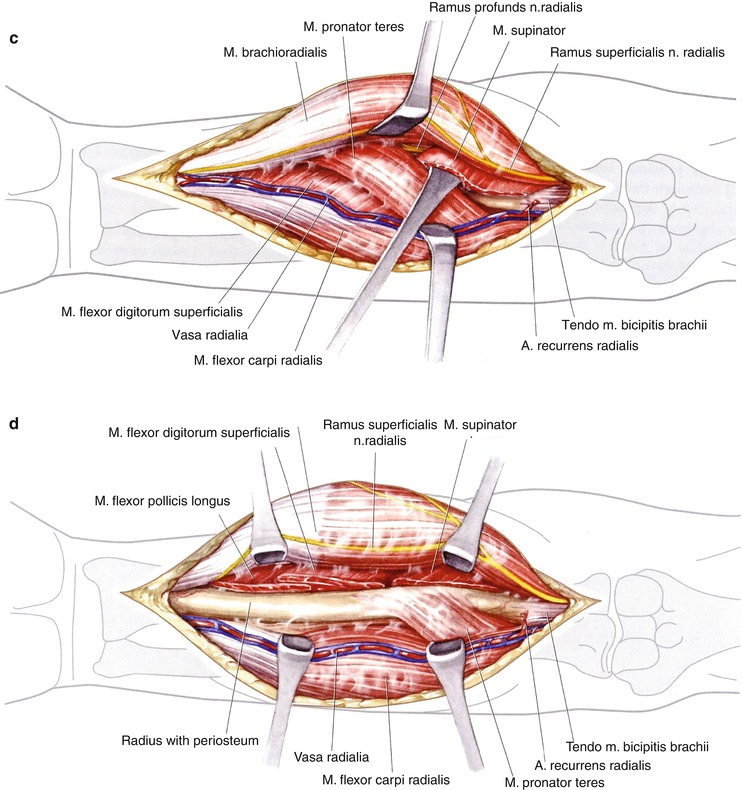

Exposure of the anterior surface of the radius is both safer and more extensile than a dorsal exposure (Fig. 12.3a–d) [3]. A straight longitudinal incision along a line between the lateral margin of the biceps tendon at the elbow and the radial styloid process at the wrist will afford access to the plane between the mobile wad and the flexor musculature of the forearm. This incision falls roughly between brachial cutaneous nerves. The deep fascia is incised adjacent to the medial border of the brachioradialis and a plane is developed between this radial nerve-innervated muscle and the median nerve-innervated flexor carpi radialis and pronator teres muscles. Dissection is initiated distally and proceeds proximally following the course of the radial artery. Arterial branches to the brachioradialis and the recurrent radial artery arising near the elbow are ligated and the radial artery is mobilized and retracted medially with the flexor carpi radialis muscle. The superficial radial nerve is encountered on the undersurface of the brachioradialis and remains lateral with this muscle [2].

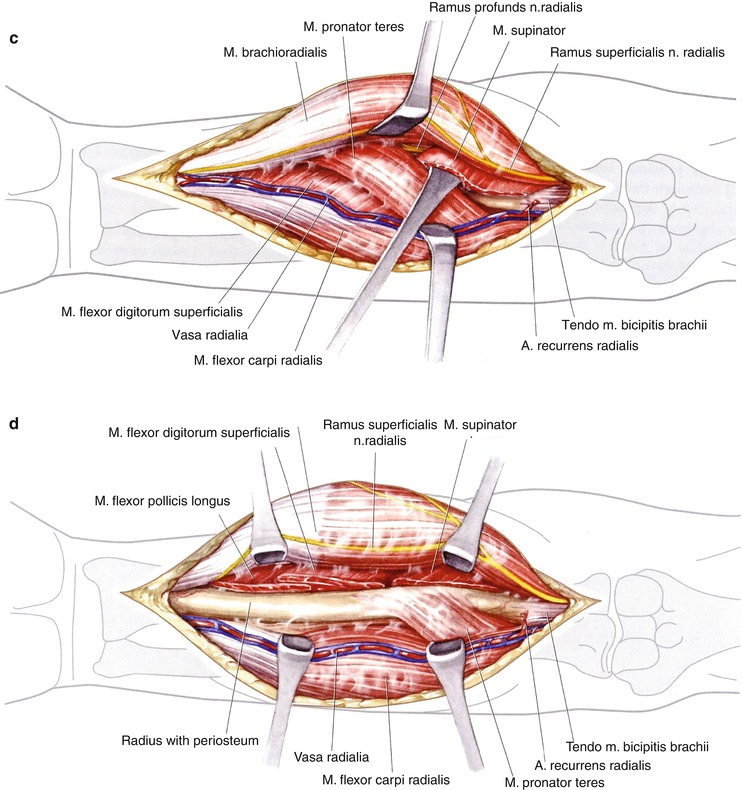

Fig. 12.3

Volar approach to the radius. The skin incision is on a line between the insertion of the biceps tendon and the radial styloid process (a). Thereafter, the incision follows the ulnar border of the brachioradialis muscle and the flexor carpi radialis m. Care must be taken of the cutaneous antebrachii n. on the brachioradialis m. (b). Mobilization of the of the brachioradial m. towards radial after ligation of braches of the radial artery. Underneath the brachioradialis m., the superficial branch of the radial n. can be seen. Incision of the fascia is at the lateral border of the biceps tendon. Preparation between the biceps tendon and flexor carpi radialis on one side and brachioradialis m. on the other side. Ligation of the radial recurrens artery. In full supination, approach to the radius at lateral border of the biceps tendon. The supinator m. is detached at the radial insertion (c). Under pronation, the proximal part of the radius is prepared. The deep branch of the radial nerve is dorsal and lateral. For the approach to the mid- and distal part of the radius, the pronator teres m. and the flexor digit. superfic. m. are detached in full supination (d)

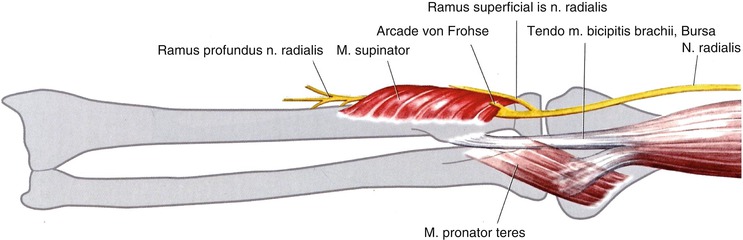

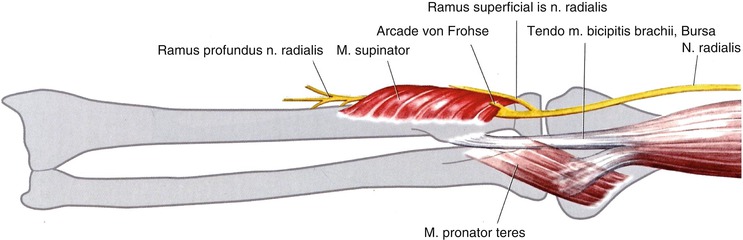

Deep dissection is initiated proximally where the biceps tendon is followed towards its insertion on the bicipital tuberosity of the radius. Full supination of the forearm displaces the posterior interosseous nerve laterally and brings the insertion of the supinator muscle anterior. The insertion of the supinator muscle is identified by the deepening of the muscular plane along the lateral aspect of the biceps tendon. Here, one may encounter a bursa between the biceps tendon and the supinator, which further facilitates this dissection. The posterior interosseous nerve (Fig. 12.4) remains well protected within the substance of the supinator muscle during elevation of its insertion from the radius, provided that excessive lateral traction is not applied.

Fig. 12.4

Position of the radial nerve

The insertion of the pronator teres must be detached and the body of the flexor digitorum superficialis elevated in order to expose the midportion of the radius. This is performed by pronating the arm in order to bring the lateral limit of these structures into view.

12.5 Surgical Technique

Conservative treatment of forearm shaft fractures results in a poor functional outcome, with the exception of the rare case of undisplaced fractures. Therefore, nearly all forearm shaft fractures are indications for plate osteosynthesis and early functional treatment (Fig. 12.5). Tissue of the forearm tends to scar. Therefore, special care of soft tissue is needed: adequate skin incision, indirect reduction when necessary, only 2–3 mm dissection of the periosteum, no direct pressure, and denudation by Hohmann retractors. Reduction starts in complete forearm shaft fractures with the least severe fracture in most instances: the ulna.

Fig. 12.5

Serial fractures of the humerus, radius and ulna. Plate fixation of all fractured bones in one surgery. X-rays preoperatively and 6 weeks postoperatively

12.5.1 Reduction Technique

Transverse or short oblique fractures of the radius or ulna are mostly easy to reduce and should always be approached first. Reduction can usually be obtained by manipulating either fragment with fine-pointed reduction forceps. An alternative is to loosely fix the plate (minimum seven–hole, 3.5-mm limited contact-dynamic compression plate (LC-DCP) or LCP (less contact plate)) with one screw to the main fragment and to subsequently reduce the opposite fragment to the plate. Attention must be paid to any rotational malalignment. We fix simpler fractures initially with a plate and two screws and then approach the other bone with the more complex fracture pattern. Once both bones have been stabilized, pronation and supination are controlled. As soon as there are one or more intermediate fragments, the indirect reduction technique should be applied. Again, usually a long 8- to 10-hole plate is fixed to one main fragment with one screw only. Close to the opposite end of the plate, a 3.5-mm cortical screw is introduced into the other main fragment. With the help of a small lamina spreader, which is placed between that screw head and the free end of the plate, distraction of the fracture can be obtained, thus allowing the fragments to fall into place or to be gently manipulated without stripping their soft tissue attachments. The plate can then be fixed to the bone as a bridge plate, not interfering with the comminuted area at all. If, on the other hand, some larger fragments can be fitted back anatomically, they should be fixed by small interfragmentary lag screws, always from the main fragment, while axial compression may be added by eccentric screw placement. Today, the implant of choice for both forearm bones is the 3.5-mm LC-DCP or LCP (Fig. 12.6).

Fig. 12.6

Multiple-injured patient. Segmental fracture of the radius and distal ulna fracture. X-rays 6 weeks and 1 year after accident

Autogenous bone grafts are only suggested if there is a substantial bony defect or if the vitality of the fracture zone appears questionable (i.e., too extensive damage or exposure). Bone grafts should not, however, be placed close to the interosseous membrane.

12.6 Galeazzi Fracture

12.6.1 Definition

This uncommon injury involves a fracture of the shaft of the radius at the junction of the middle and distal thirds in association with dislocation at the distal radioulnar joint [4].

12.6.2 Biomechanics

Currently, most favour a mechanism that includes axial loading of a hyperpronated forearm [5]. As displacement continues, the force may be transmitted via the interosseous membrane to the ulna, causing dislocation of the ulnar head and tearing of the triangular fibrocartilage complex, with resultant loss of its stabilizing influence on the distal radioulnar joint [5].

12.6.3 Radiographic Findings

These include:

1.

A short oblique fracture of the radius with dorsal angulation as seen on the lateral radiograph

2.

Shortening of the radius in relationship to the distal ulna on the anteroposterior radiograph

3.

Fracture of the ulnar styloid at its base

4.

Widening of the distal radioulnar joint space on the anteroposterior radiograph

5.

Dorsal displacement of the ulna relative to the radius, seen best on a true lateral radiograph

The last three findings, if associated with radial shortening of more than 5 mm, are suggestive of traumatic disruption of the distal radioulnar joint [6].

12.6.4 Treatment

Inability to reduce the distal radioulnar joint or its redislocation was originally thought to be an infrequent occurrence. If the distal radioulnar joint is reducible but unstable with forearm rotation, there exist several treatment alternatives. In those cases associated with a fracture of the ulnar styloid at its base, open reduction and internal fixation of the styloid fracture is recommended, using either Kirschner wires in conjunction with a tension band or a small screw.

Should there be no associated ulnar styloid fracture, the distal ulna may be transfixed to the radius using Kirschner wires with the forearm in 40° of supination. In this case, an above-elbow cast is recommended for 6 weeks. The Kirschner wires are removed after 6 weeks [7].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree