Chapter 21 Foot and Ankle Injuries in Dancers

Introduction

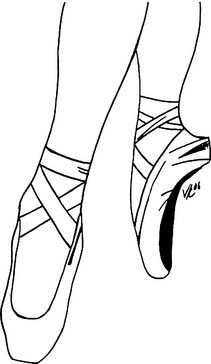

Female dancers spend a considerable time en pointe, or on the points of the toes (Fig. 21-1), whereas male dancers tend not to dance on their toes and spend much of their time in turning, lifting, and holding ballet dancers. As such, male and female dancers tend to present with distinct injuries. In addition to the myriad of physical injuries related to female dancers that follows, female dancers also are prone to the triad of anorexia, amenorrhea, and osteoporosis. This unfortunate triad stems from the significant pressure on dancers to weigh less and less. The most disturbing data suggest that female dancers weigh more than 15% below the ideal weight for height. This has metabolic consequences leading to stress fractures and slower union rates in injured female dancers.1 In contradistinction, male dancers have fewer metabolic problems but are prone to overuse injuries from repetitive motion and to stress fractures from the sudden deceleration of large leaps, volé, sauté, or jeté.

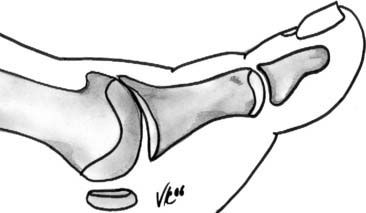

Dancer’s feet are the instruments on which their art depends. They require, in addition to an extraordinary flexibility and strength, a particular anatomic profile. Over time a dancer’s foot will evolve and only the strongest will survive. Dancers’ feet typically are “intrinsic plus:” they have narrow metatarsal width with straight toes. (Intrinsic-minus feet have wider metatarsal splaying and clawing of the toes.2) Apart from muscle strength, dancers’ feet require great flexibility. In the relevé position (Fig. 21-2) the ankle is in a vertical position—90 degrees of plantarflexion of the ankle-foot complex. The dancer also requires 90 to 100 degrees of dorsiflexion in the first metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joint to go from relevé to en pointe. These are extraordinary ranges of motion and can only be achieved with years of practice, which mold the young ballet dancer’s bones during the bone growth phase.3–5 As a result of endless practice barres, class, and training, dancers’ feet tend to be cavus and have thickened metatarsals to support when en demi-pointe. Calluses abound secondary to pressure demands on the skin.

In general, five types of dancer’s feet have been described:6

The following is a review of the more common dance injuries and problems in the foot and ankle.

Metatarsophalangeal Joint

Bunions

Although dancing has been said to play a role in the pathogenesis of bunions, it is unlikely that this is the case. Dancers, like the rest of the population, can be either resistant or prone to develop bunions.7 In those dancers that are prone to develop bunions, it is imperative to delay surgical intervention for as long as possible. Bunion surgery adversely affects dorsiflexion of the first MTP joint, a critical motion in dancers. Most bunions can be treated with conservative methods, including toe spacers and horseshoe pads. The senior author has seen several aspiring young dancers whose careers were ended by well-meaning bunion surgery. If a bunion is precluding the dancer from activity and surgery is warranted, then a chevron osteotomy can provide pain relief and stability without compromising motion.

Hallux Rigidus

The treatment of hallux rigidus depends on the grade of the disease (Fig. 21-3).

In grade II disease, the joint is involved, with minor cartilage destruction evident as joint space narrowing on plain radiograph. Treatment involves resection of marginal osteophytes (cheilectomy). In addition, the dorsal one third of the metatarsal head is resected.8 Intraoperative dorsiflexion of the hallux greatly overestimates the degree of motion that can be expected following surgery. Just over half of what is achieved at the time of surgery will be evident in the postoperative follow-up examination. It is important that dancers understand that, although surgery will make the condition better, the joint will never be normal. In addition, the length of recovery time must be discussed with the dancer, because a full functional recovery often takes 6 months. To improve functional motion following surgery, a dorsally based closing osteotomy can be used (Moberg). This procedure improves dorsiflexion but at the expense of plantarflexion, and the dancer should be warned of this.

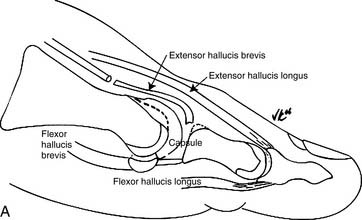

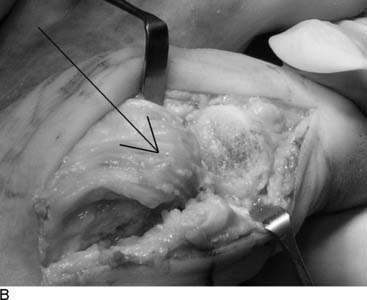

Grade III hallux rigidus presents with dorsal and lateral osteophytes in addition to clear degenerative arthrosis on both sides of the joint. Arthrodesis, an acceptable surgical option in the general population, is not feasible in a career dancer. To preserve motion, a capsular arthroplasty can be performed with reproducible outcomes9 (Fig. 21-4, A and B). It is important to select these patients carefully because transfer metatarsalgia is common in those patients with a foreshortened first ray.

Sesamoiditis

Other conditions may mimic sesamoiditis, including instability, bursitis, and nerve entrapment:

Lesser Metatarsophalangeal Joints

MTP Instability

As the dancer relevés the phalanx subluxes dorsally, pushing the metatarsal head plantarward and causing pain. In the demi-pointe position, excessive loads are transmitted through the second and third MTP joints. Clinical examination will elicit a translation in the anterior-posterior (AP) plane that is in excess of the adjacent joints.10 Treatment initially is directed at taping to neighboring toes and stress-relieving padding. Surgical correction includes a very limited resection arthroplasty with a plantar condylectomy. Alternately, a limited Weil osteotomy may be used with screw fixation. Motion is begun early. Scarring at the plantar aspect of the wound facilitates tightening of the redundant plantar plate.

Freiberg’s Infraction

Dancers have a propensity to develop Freiberg’s infraction equal to that of the general population. In general, conventional radiography lags behind clinical symptoms by up to 6 months (Fig. 21-5). Bone scan or MRI facilitate early diagnosis.

Four types of infraction occur:

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree