Congenital and Acquired Short Heel Cord

1. Definition—Deformity

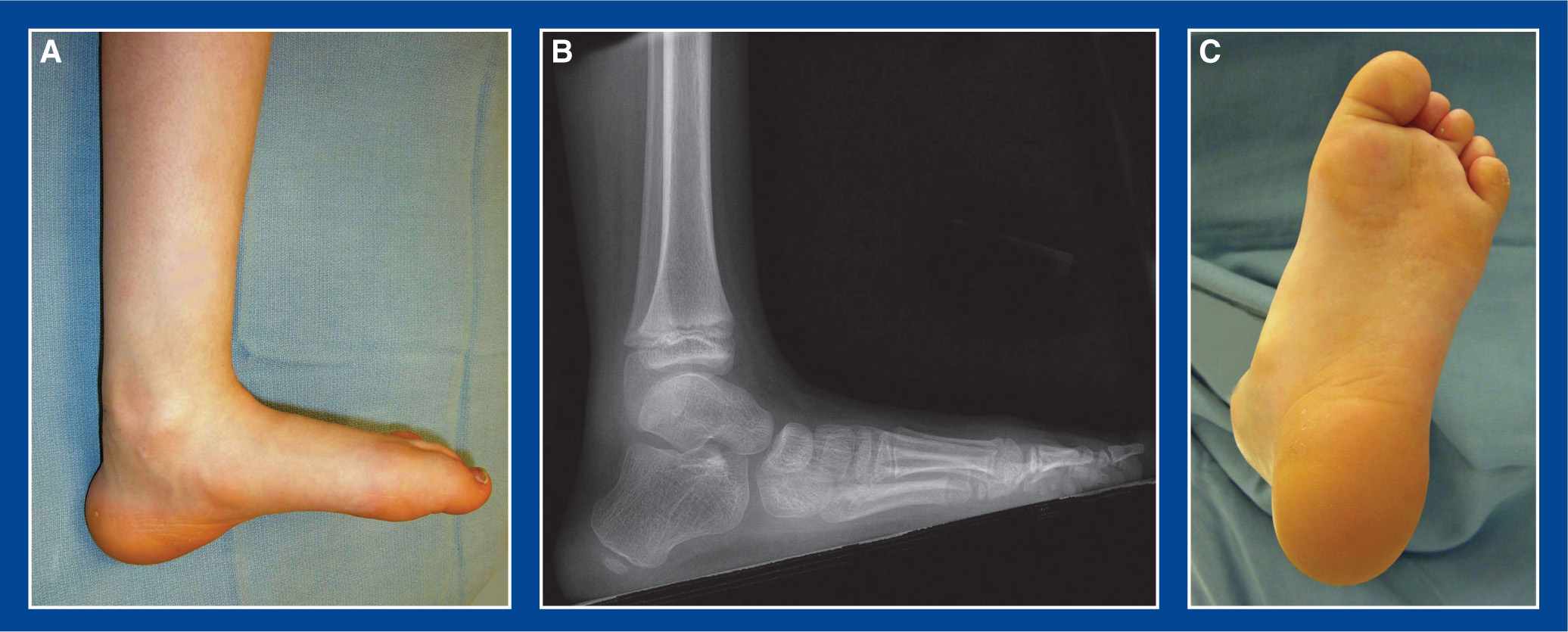

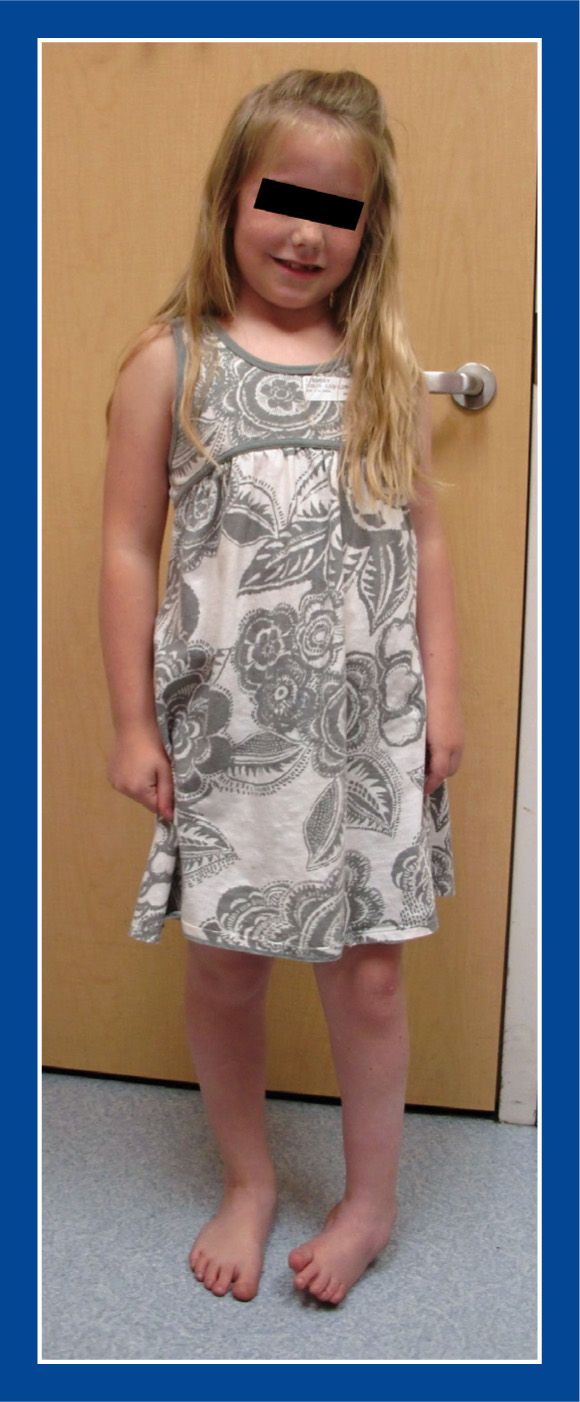

a. Congenital or acquired contracture of the gastrocnemius or triceps surae (gastrocnemius and soleus) in an otherwise normal child with normal nerves, muscles, and bones (Figure 5-1)

b. Acquired contracture of the gastrocnemius or triceps surae (gastrocnemius and soleus) in a child with a neuromuscular disorder

c. Often associated with other idiopathic and acquired deformities

2. Elucidation of the segmental deformities

a. Ankle—plantar flexed (equinus)

i. Inability to dorsiflex the ankle to at least 10° above neutral with the subtalar joint held in neutral alignment (see Assessment Principle #12, Figure 3-13, Chapter 3)

• If it is possible to achieve 10° of dorsiflexion with the knee flexed but not with it extended, the gastrocnemius alone is contracted.

• If it is not possible to achieve 10° of dorsiflexion regardless of whether the knee is flexed or extended, the triceps surae (gastrocnemius and soleus) is contracted.

3. Imaging

a. None absolutely necessary

b. Standing anteroposterior (AP) and lateral of foot (optional)

c. Standing AP, lateral, and mortis of ankle (optional)

4. Natural history

a. Although never formally studied, congenital contracture of the gastrocnemius muscle or the triceps surae probably persists

b. Acquired contractures generally increase in severity or persist at an unacceptable degree

5. Nonoperative treatment

a. Accept it

b. Wear high heels

c. Twice (or more) daily heel cord stretching exercises along with nighttime dorsiflexion maintenance bracing

d. Serial short-leg stretching casts—for children up to around 5 years of age—followed by nighttime dorsiflexion maintenance bracing

6. Operative indications

a. Failure of nonoperative treatment to achieve and maintain at least 10° of ankle dorsiflexion above neutral with the subtalar joint in neutral alignment and the knee extended, if this lack of flexibility causes:

i. pain under the metatarsal (MT) heads,

ii. pain along the Achilles musculotendinous continuum, and/or

iii. functional disability with gait disturbance.

7. Operative treatment with reference to the surgical techniques section of the book for each individual procedure

a. Gastrocnemius recession (see Chapter 7)—perform this for an isolated contracture of the gastrocnemius, based on the Silfverskiold test (see Assessment Principle #12, Figure 3-13,Chapter 3)

b. Tendo-Achilles Lengthening (TAL) (see four techniques in Chapter 7)—perform this for contracture of the triceps surae (gastrocnemius and soleus), based on the Silfverskiold test (see Assessment Principle #12, Figure 3-13, Chapter 3). The considerations for which technique to use are elucidated in Chapter 7.

i. Percutaneous triple cut

ii. Mini-open double cut slide

iii. Open double cut slide

iv. Open Z-lengthening

Figure 5-1. Toe-standing/walking due to congenital contracture of the gastrocnemius muscles in an otherwise normal child.

Positional Calcaneovalgus Deformit

1. Definition—Deformity

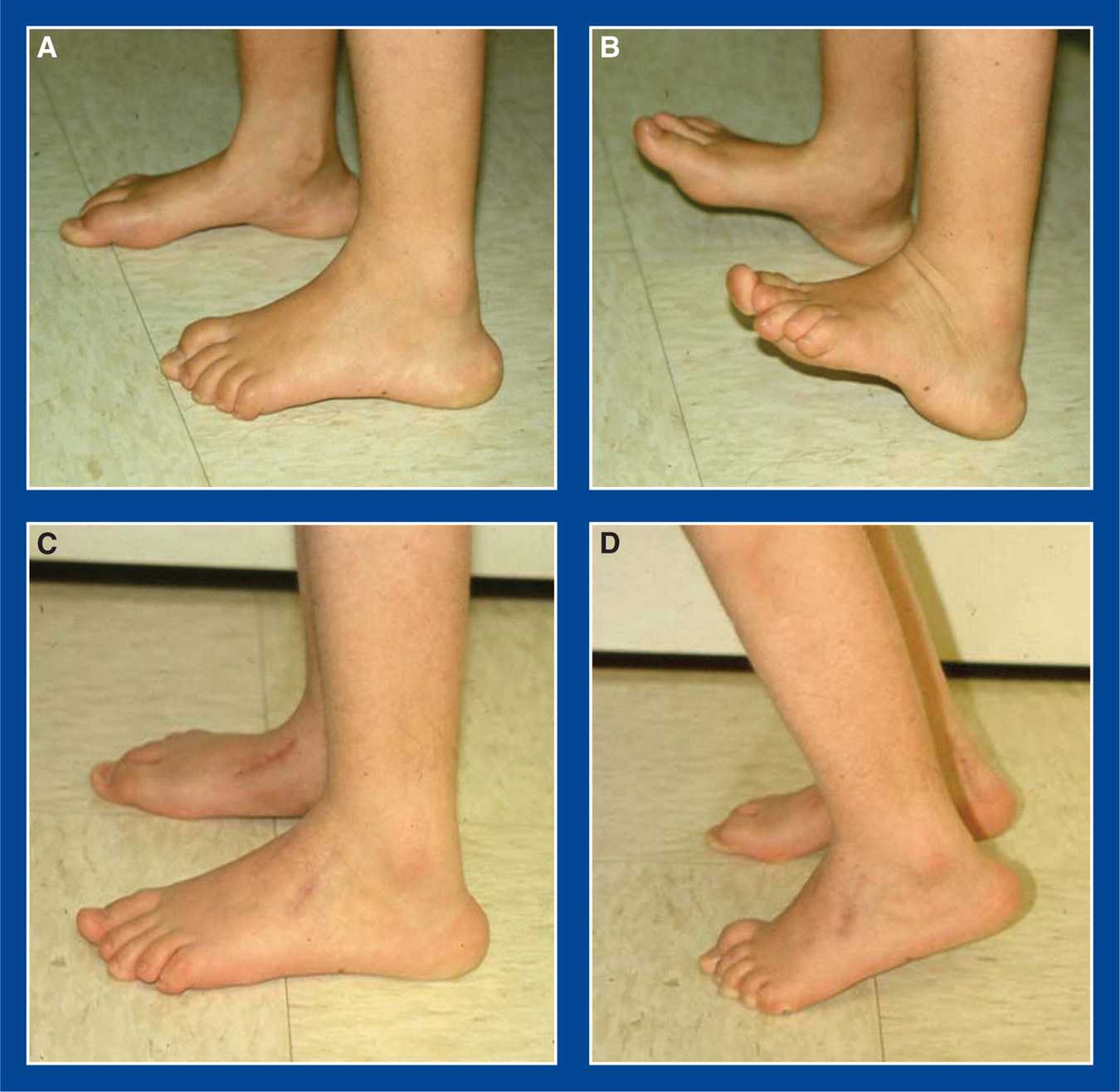

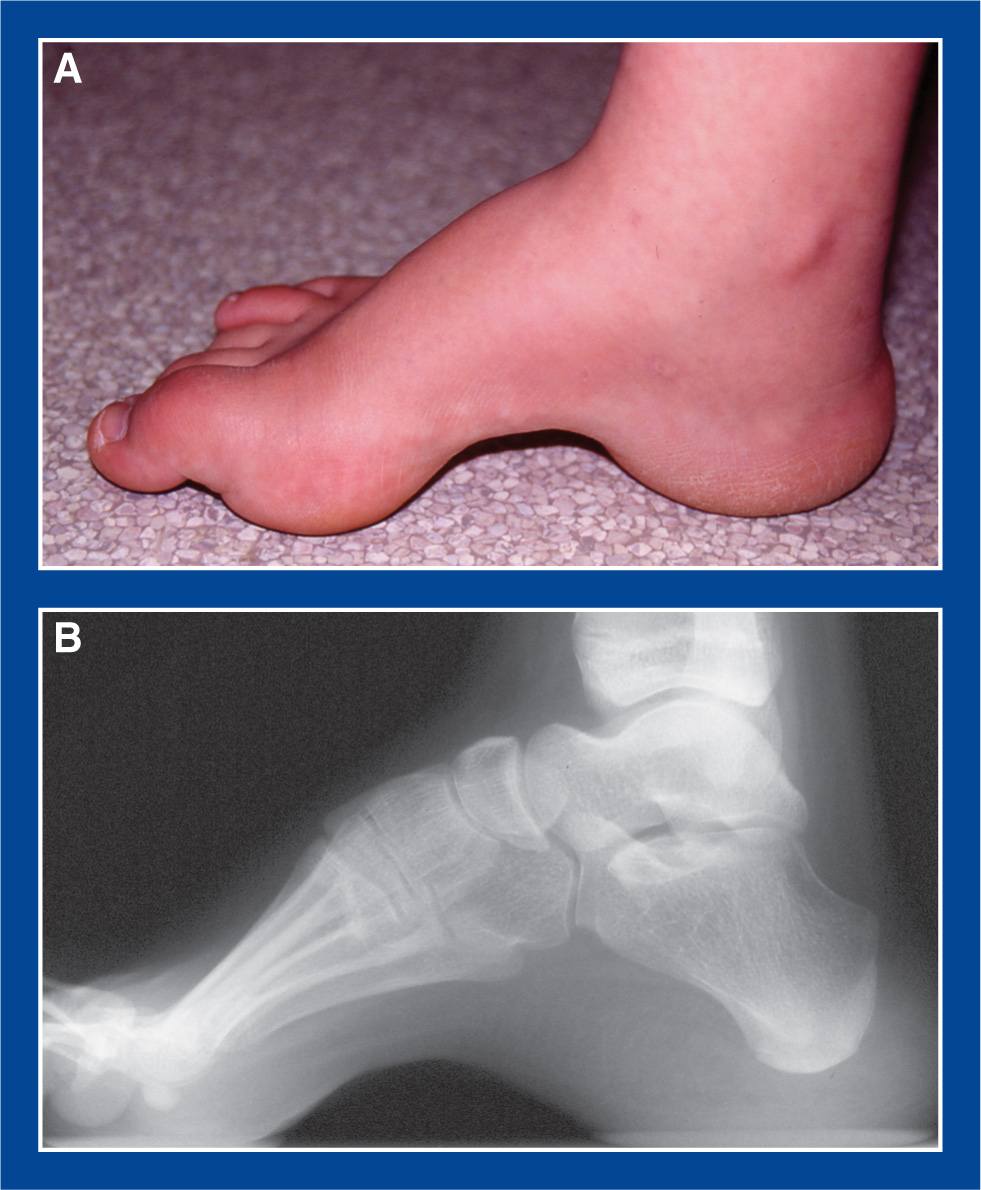

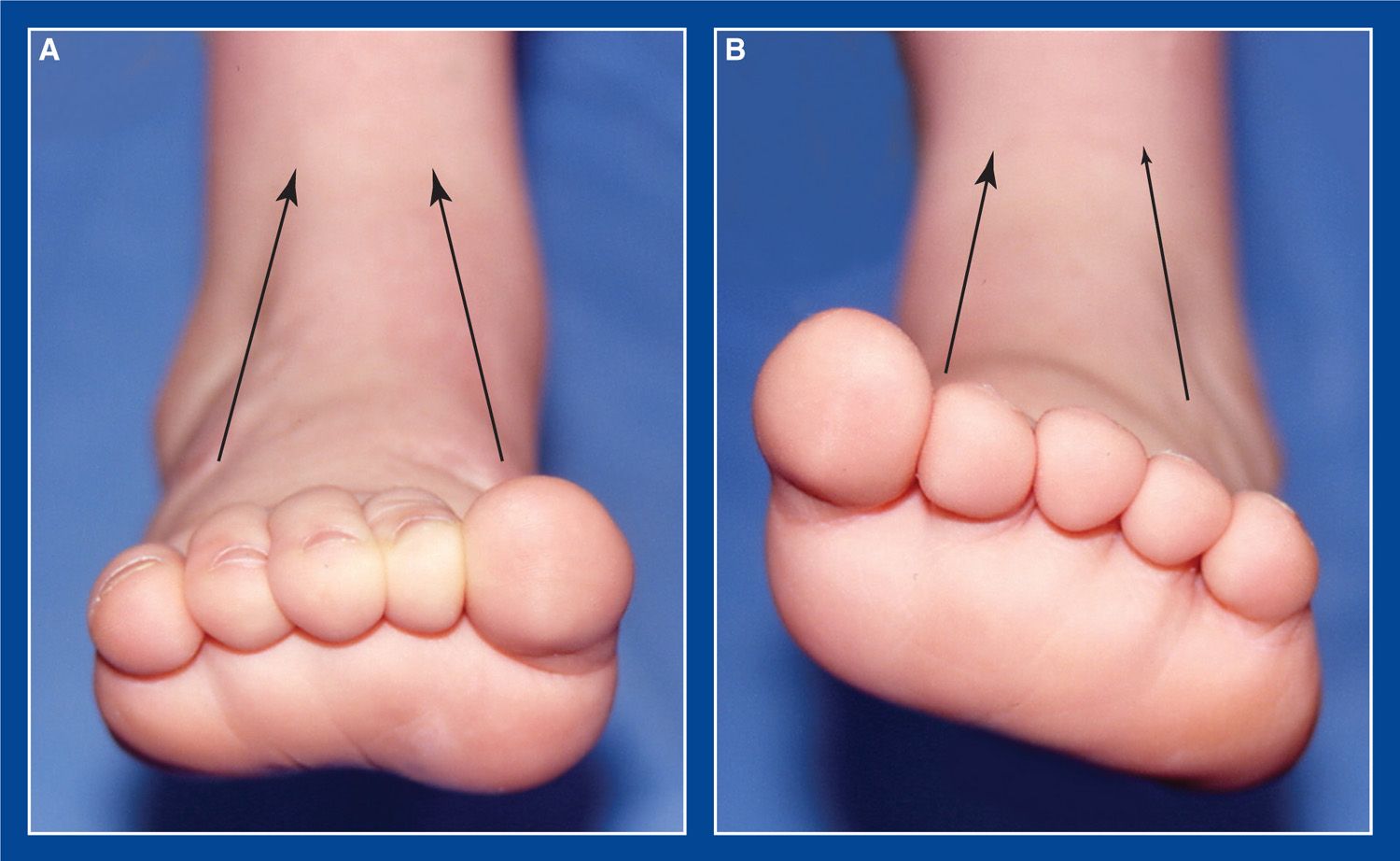

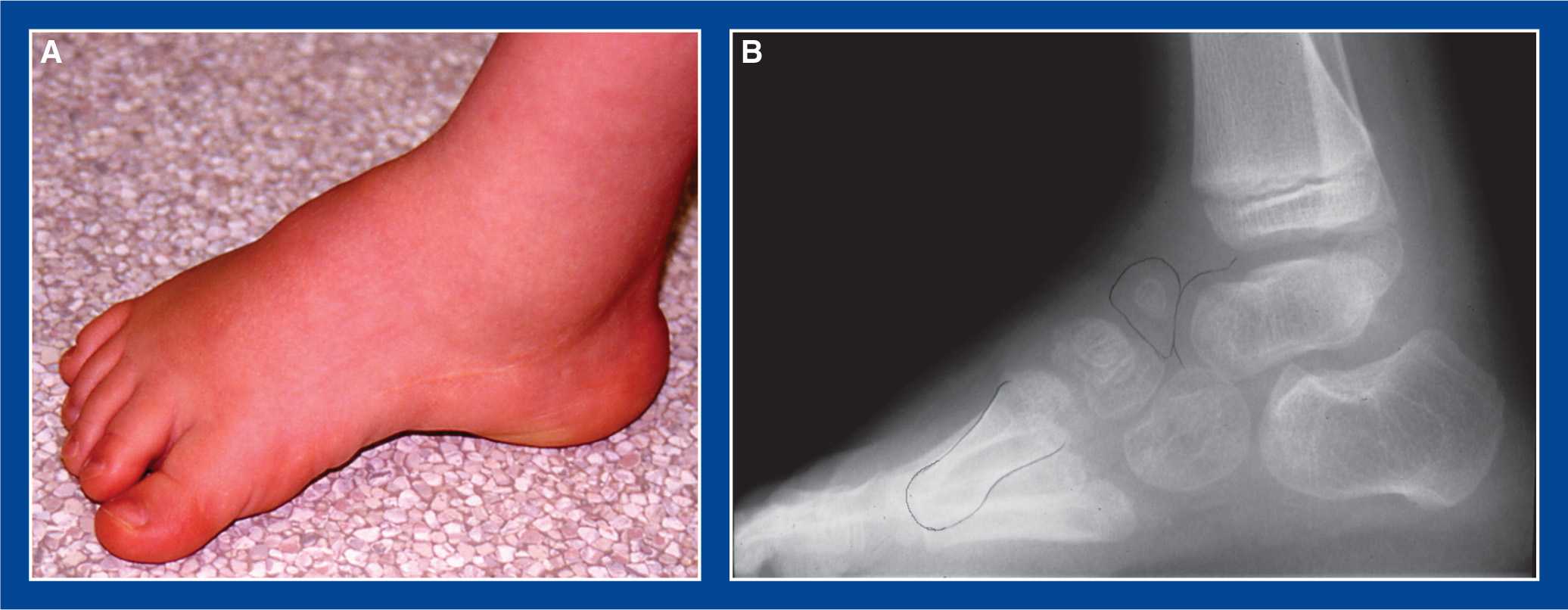

a. Congenital positional hyperdorsiflexion and valgus deformity of the hindfoot (Figure 5-2A)

b. Differential diagnosis is (Figure 5-2):

i. Congenital vertical/oblique talus

ii. Posteromedial tibial bowing

iii. Paralytic calcaneus deformity

2. Elucidation of the segmental deformities

a. Forefoot—neutral

b. Midfoot—neutral

c. Hindfoot—valgus/everted or neutral

d. Ankle—dorsiflexed (calcaneus)

3. Imaging

a. None, unless physical examination findings are equivocal

4. Natural history

a. 100% of these correct completely without intervention

5. Nonoperative treatment

a. None

b. Parents can be instructed to perform daily plantar flexion stretching exercises. It might not make any difference in the rate of correction of the deformity, but it does no harm. Formal physical therapy is not indicated!

6. Operative indications

a. None

7. Operative treatment with reference to the surgical techniques section of the book for each individual procedure

a. Not applicable

1. Definition—Deformity

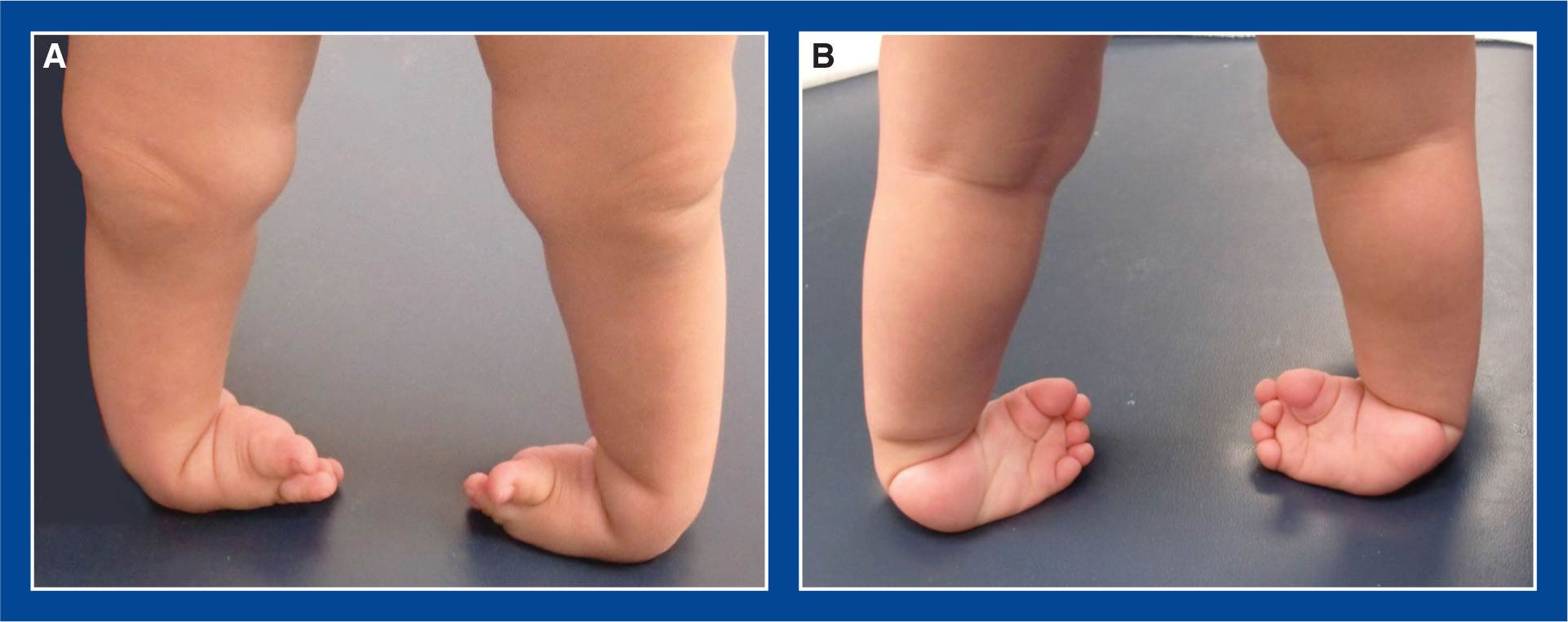

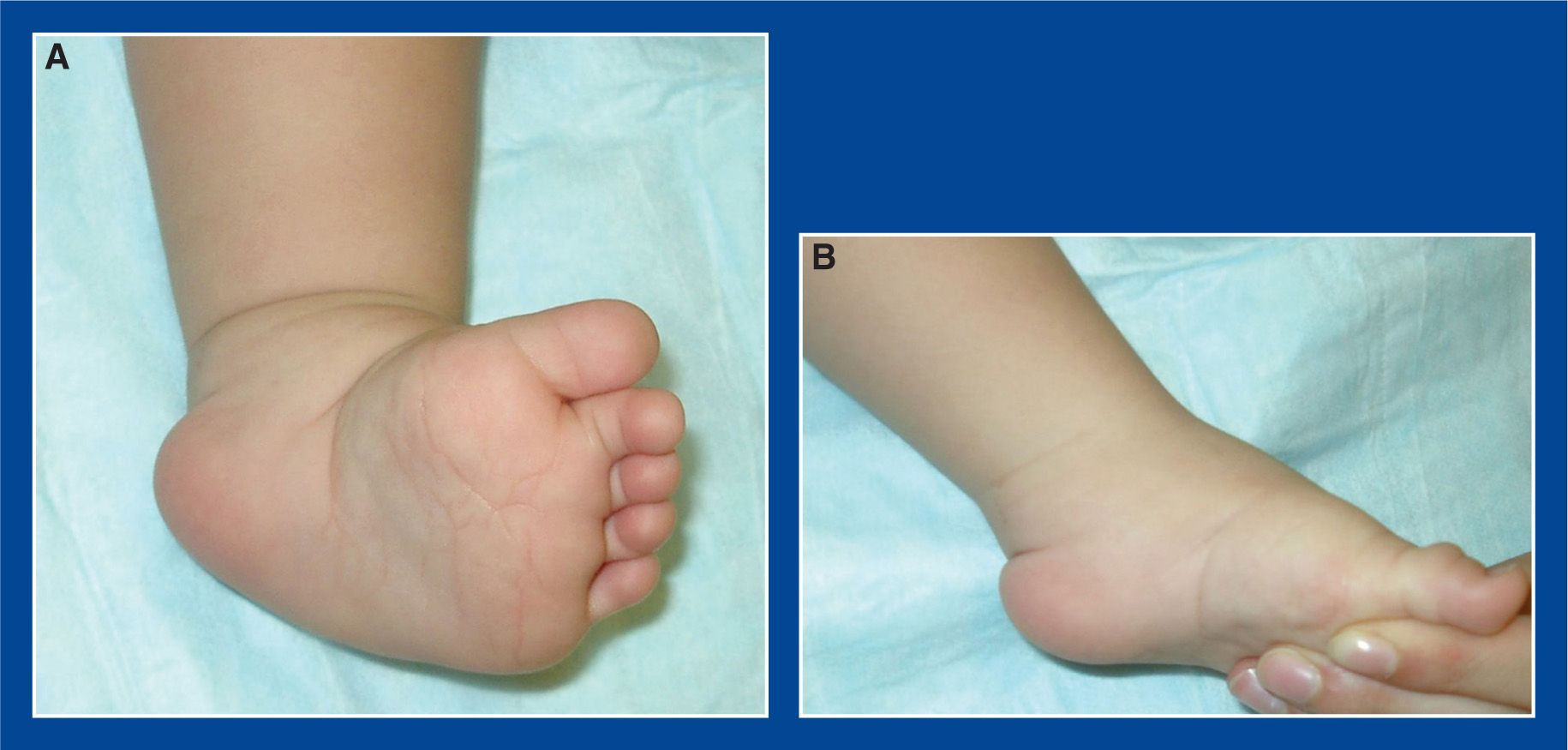

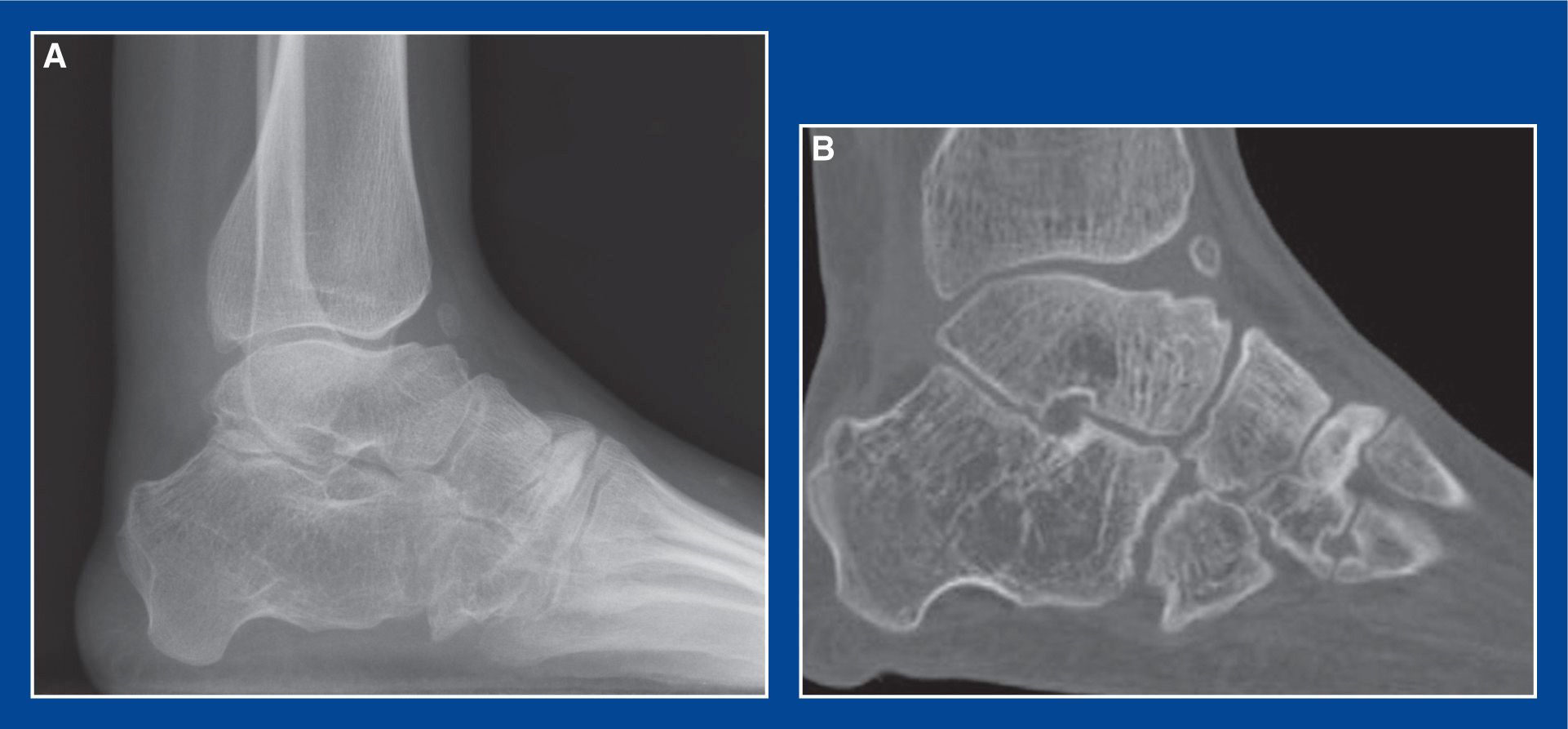

a. Calcaneus (hyperdorsiflexion) deformity of the ankle due to a weak triceps surae and a strong anterior tibialis (Figure 5-3)

b. Due to:

i. static muscle imbalance

• myelomeningocele, lipomeningocele, postpoliomyelitis

ii. acquired muscle imbalance

• tethered cord in myelomeningocele, lipomeningocele

iii. surgical overlengthening and/or weakening of the triceps surae, as in cerebral palsy and multiply operated clubfoot

Figure 5-2. Differential diagnosis for positional calcaneovalgus deformity. A. Positional calcaneovalgus. The longitudinal arch is present and the forefoot can be further plantar flexed on the hindfoot with gentle manipulation. Full passive ankle plantar flexion is not possible at birth. B. CVT. The longitudinal arch cannot be created by passive plantar flexion of the forefoot on the hindfoot. C. Posteromedial tibial bowing photo and x-ray. The deformity is actually in the tibia. The foot is well-shaped and flexible. D. Paralytic calcaneovalgus in a child with myelomeningocele. Weak/absent plantar flexors are noted, and there is the obvious lesion at the base of the spine.

Figure 5-3. A. Medial view of a calcaneus foot deformity in a child with myelomeningocele. The heel pad is large, thick, and callused from excessive load-bearing. B. Matching lateral x-ray. C. Plantar view of the foot showing the large, thick, and callused heel pad, but less than normal callus formation under the MT heads.

2. Elucidation of the segmental deformities

a. Ankle—dorsiflexion (calcaneus)

3. Imaging

a. Standing AP and lateral of foot (Figure 5-3)

b. AP, lateral, and mortis of ankle

4. Natural history

a. Persistence of deformity, with

i. progressive increase in callus formation on the plantar aspect of the heel

ii. eventual fissuring of the hypertrophic and callused skin of the heel pad

iii. ultimately, plantar heel ulceration

iv. Pain is rarely a clinical problem because this deformity occurs most commonly in children with myelomeningocele and lipomeningocele, who have insensate skin.

b. Progressive increase in crouched gait with gradual decrease in walking endurance. The underlying triceps surae muscle weakness, compounded by increased body weight with advancing age, leads to lever arm dysfunction (see Basic Principle #7, Figure 2-10, Chapter 2).

c. Poor brace integrity with rapid failure of the plastic at the ankle of the ankle-foot-orthotic (AFO)

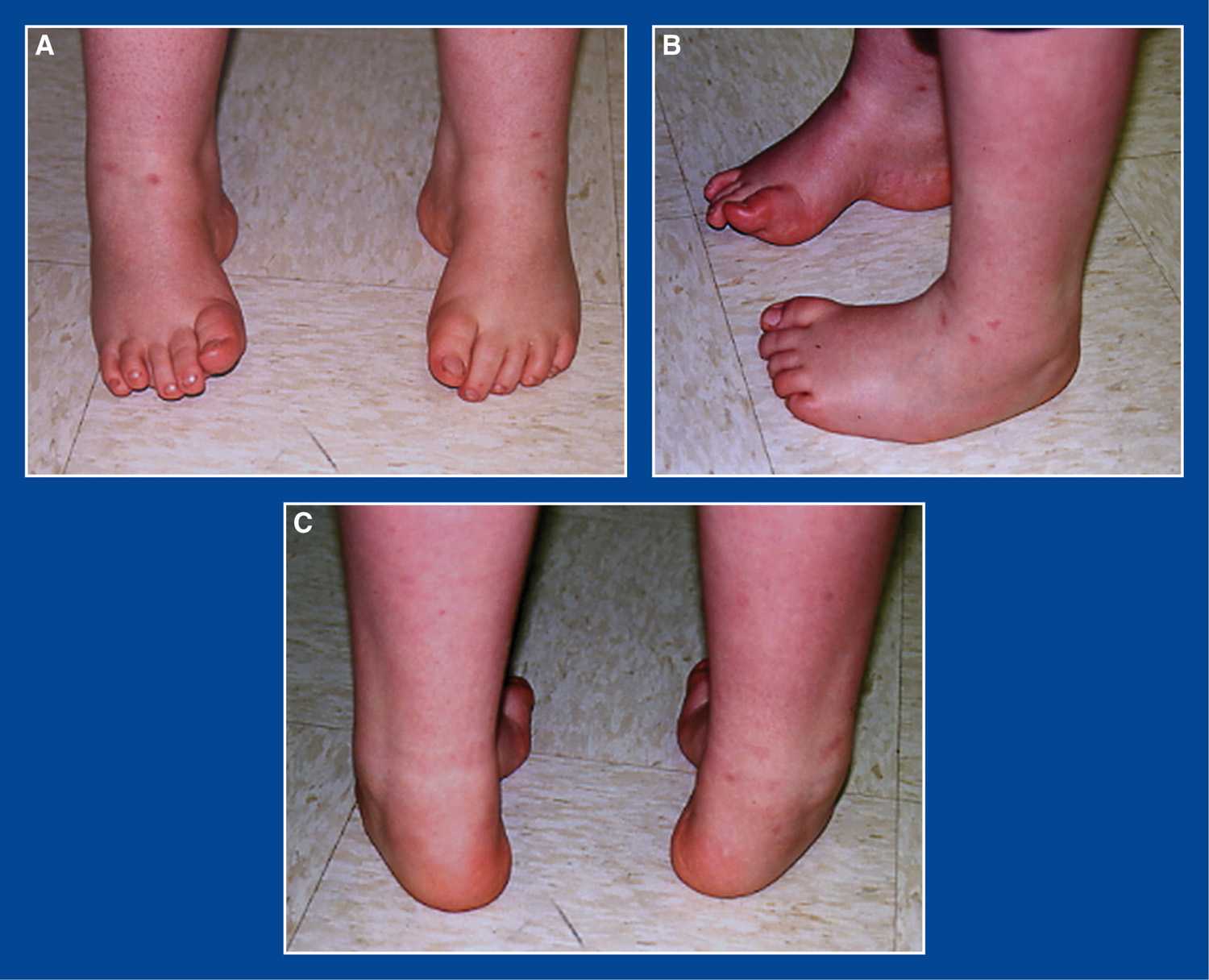

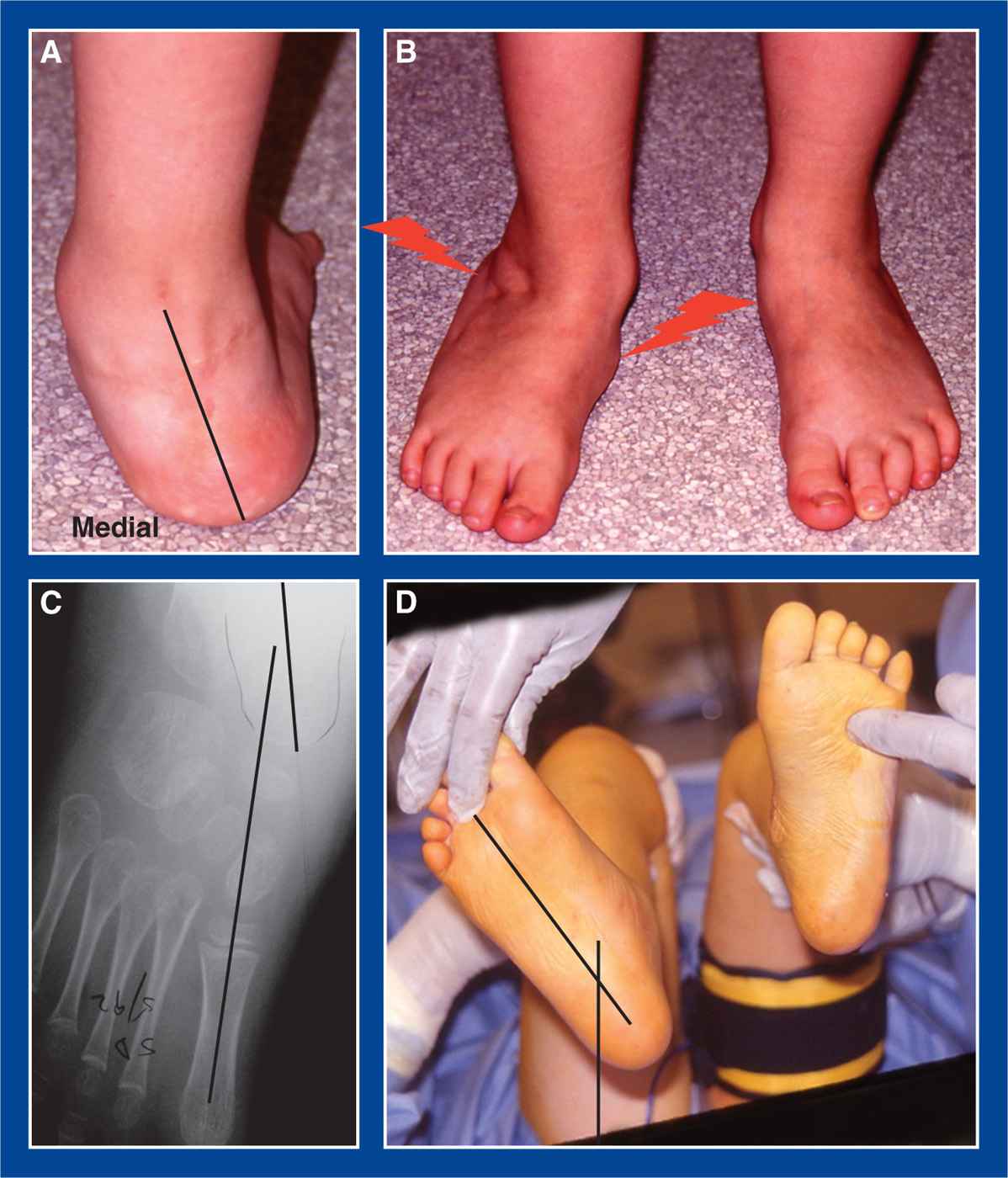

Figure 5-4. Child with L5 level myelomeningocele and calcaneus foot deformities. A. Preop lateral photos. Note the large, callused heel pads. B. She can easily heel stand, but cannot toe stand. C. One year after transfer of her anterior tibialis tendons to her tendo-Achilles, her heel pads are smaller and less callused. The peroneus tertius was released through the dorsolateral incision (not usually required). D. She was able to toe stand, though in only slightly greater than 5° of active plantar flexion. This transfer usually functions as a tenodesis that does not eliminate the need for ankle-foot orthoses, but it improves or eliminates the crouched gait and increases the useful life of the AFOs.

5. Nonoperative treatment

a. Body weight reduction

b. Increase rigidity of the AFO

6. Operative indications

a. Failure of nonoperative attempts to maintain walking endurance and heel skin integrity

7. Operative treatment with reference to the surgical techniques section of the book for each individual procedure

a. Anterior tibialis tendon transfer to the tendo-Achilles (see Chapter 7, Figure 7-27; Figure 5-4)

Valgus Deformity of the Ankle Joint

1. Definition—Deformity

a. Persistence of neonatal valgus orientation of the ankle joint after age 4 to 5 years (see Assessment Principle #11, Figure 3-12, and Assessment Principle #21, Figure 3-27, Chapter 3)

2. Elucidation of the segmental deformities

a. Ankle—valgus

i. Greater than 4° of valgus orientation of the articular surface of the distal tibia compared with the axis of the tibial shaft after the age of 4 to 5 years

3. Imaging

a. AP, lateral, and mortis of the ankle (see Assessment Principle #21, Figure 3-27, Chapter 3)

4. Natural history

a. Valgus orientation of the ankle joint is normal from birth (actually, from the time of in utero joint formation at 7 to 9 weeks’ gestation) until approximately age 4 to 5 years. The valgus alignment gradually corrects to neutral by that age in most normal children.

b. Valgus orientation of the ankle joint is reclassified as a deformity if it persists after approximately age 4 to 5 years

i. The average lateral distal tibia angle (LDTA) after age 4 to 5 years is 89° (1° of valgus), with the normal range of 86° to 92° (4° of valgus to 2° of varus); therefore, >4° of valgus is abnormal.

c. Congenital valgus orientation of the ankle joint persists as a deformity in:

i. up to 66% of limbs with clubfoot deformity

ii. fibula hemimelia, often as a ball-and-socket joint

iii. essentially all limbs affected by myelomeningocele, lipomeningocele, poliomyelitis, spinal cord tumor or injury, and other lower extremity paralyzing conditions (not cerebral palsy) that affect young children

d. Valgus deformity of the ankle can develop following:

i. injury to the lateral distal tibial physis and/or distal fibula physis

ii. fibula pseudarthrosis in congenital anterolateral bowing of the tibia and fibula, with or without tibial pseudarthrosis and with or without neurofibromatosis

e. Persistent and developmental valgus deformities of the ankle joint can cause:

i. lateral ankle/hindfoot pain from impingement of the lateral malleolus, peroneal tendons, and calcaneus

ii. medial ankle/hindfoot pain from stretch of the medial ankle joint and subtalar joint ligaments

iii. plantar–medial heel pain due to excessive loading on that area of the heel pad

iv. skin pressure irritation and/or pain under the medial malleolus due to weight-bearing on the firm shoe counter or on the hard plastic of an AFO (in children with paralytic conditions)

5. Nonoperative treatment

a. None indicated for asymptomatic cases

b. Over-the-counter, cushioned, semirigid arch supports (Figure 5-31) to invert the neutral subtalar joint into varus to compensate for the valgus deformity of the ankle joint. These are contraindicated if the gastrocnemius or entire triceps surae is contracted.

c. Adjust or modify the padding in an AFO in a child with an underlying paralytic condition

6. Operative indications

a. Failure of nonoperative treatment to relieve the:

i. lateral ankle/hindfoot pain from impingement of the lateral malleolus, peroneal tendons, and calcaneus

ii. medial ankle/hindfoot pain from stretch of the medial ankle joint and subtalar joint ligaments

iii. skin pressure irritation and/or pain under the medial malleolus due to weight-bearing on the shoe counter or the hard plastic of an AFO (in a child with an underlying paralytic condition)

b. Progressive valgus deformity due to injury to the lateral distal tibial physis and/or distal fibula physis

7. Operative treatment with reference to the surgical techniques section of the book for each individual procedure

a. Medial distal tibia guided growth with retrograde medial malleolus screw (see Chapter 8)—perform this in a skeletally immature child

b. Distal tibia and fibula valgus-correction osteotomies (see Management Principle #20, Figures 4-10 and 4-12, Chapter 4), (see Chapter 8)—perform this in a skeletally mature adolescent

c. Resection and fat grafting of the physeal bar (if appropriate) with or without concurrent distal tibia and fibula valgus-correction osteotomies (see Chapter 8)—perform this in a skeletally immature child with a small physeal bar

d. Completion of the distal tibial and fibula growth arrests (epiphysiodeses) with concurrent distal tibia and fibula valgus-correction osteotomies (see Chapter 8)—perform this in a skeletally immature child with a large, irresectable physeal bar

Valgus Deformity of the Ankle Joint and the Hindfoot

1. Definition—Deformities

a. Valgus orientation of the ankle joint after age 4 to 5 years (see Assessment Principle #11, Figure 3-12, and Assessment Principle #21, Figure 3-27, Chapter 3) and

b. Valgus deformity of the hindfoot, with or without eversion of the subtalar joint, as seen in:

i. Idiopathic flatfoot

ii. Congenital vertical talus (CVT)

iii. Congenital oblique talus (COT)

iv. Skewfoot

v. Tarsal coalition

vi. Congenital talocalcaneal synostosis associated with

• fibula hemimelia

• tibial hemimelia

• lower extremity hemiatrophy

• other syndromes and chromosome abnormalities

vii. Overcorrected clubfoot

• translational

• rotational

2. Elucidation of the segmental deformities

a. Hindfoot—valgus or valgus/eversion

b. Ankle—valgus

i. Greater than 4° of valgus orientation of the articular surface of the distal tibia compared with the axis of the tibial shaft after the age of 4 to 5 years

3. Imaging

a. Standing AP, lateral, and Harris axial views of the foot (see Assessment Principle #18, Figures 3-20, and 3-24, Chapter 3)

b. AP, lateral, and mortis of the ankle (see Assessment Principle #21, Figure 3-27, Chapter 3)

4. Natural history

a. Valgus orientation of the ankle joint is normal from birth (actually, from the time of in utero joint formation at 7 to 9 weeks’ gestation) until approximately age 4 to 5 years. The valgus alignment gradually corrects to neutral by that age in most normal children.

i. Valgus orientation of the ankle joint is reclassified as a deformity if it persists after approximately age 4 to 5 years

• The average LDTA after age 4 to 5 years is 89° (1° of valgus), with the normal range of 86° to 92° (4° of valgus to 2° of varus); therefore, >4° of valgus is abnormal.

ii. Congenital valgus orientation of the ankle joint persists as a deformity in:

• up to 66% of limbs with clubfoot deformity

• fibula hemimelia, often as a ball-and-socket joint

• essentially all limbs affected by myelomeningocele, lipomeningocele, poliomyelitis, spinal cord tumor or injury, and other lower extremity paralyzing conditions (not cerebral palsy) that affect young children

iii. Valgus deformity of the ankle can develop following:

• injury to the lateral distal tibial physis and/or distal fibula physis

• fibula pseudarthrosis in congenital anterolateral bowing of the tibia and fibula, with or without tibial pseudarthrosis and with or without neurofibromatosis

iv. Persistent and developmental valgus deformities of the ankle joint can cause:

• lateral ankle/hindfoot pain from impingement of the lateral malleolus, peroneal tendons, and calcaneus

• medial ankle/hindfoot pain from stretch of the medial ankle joint and subtalar joint ligaments

• plantar–medial heel pain due to excessive loading on that area of the heel pad

• skin pressure irritation and/or pain under the medial malleolus due to weight-bearing on the firm shoe counter or on the hard plastic of an AFO (in children with paralytic conditions)

b. Valgus deformity of the hindfoot, with or without eversion of the subtalar joint, can cause axial loading pain under the head of the talus and/or impingement-type pain in the sinus tarsi area

5. Nonoperative treatment

a. None indicated for asymptomatic cases

b. Over-the-counter, cushioned, semirigid arch supports (Figure 5-31) to invert the subtalar joint into varus to correct the subtalar valgus and to attempt to compensate for the valgus deformity of the ankle joint. These are contraindicated if the gastrocnemius or entire triceps surae is contracted.

c. Adjust or modify the padding in an AFO in a child with an underlying paralytic condition

6. Operative indications

a. Failure of nonoperative treatment to relieve the:

i. lateral ankle/hindfoot pain from impingement of the lateral malleolus, peroneal tendons, and calcaneus

ii. medial ankle/hindfoot pain from stretch of the medial ankle joint and subtalar joint ligaments

iii. skin pressure irritation and/or pain under the medial malleolus due to weight-bearing on the shoe counter or the hard plastic of an AFO (in a child with an underlying paralytic condition)

iv. axial loading pain under the head of the talus and/or impingement-type pain in the sinus tarsi area

b. Progressive valgus deformity due to injury to the lateral distal tibial physis and/or distal fibula physis

7. Operative treatment with reference to the surgical techniques section of the book for each individual procedure

a. Correct the ankle valgus first. There is only one, easy-to-assess, stable anatomic alignment of the ankle joint (see Management Principle #23-6, Chapter 4).

i. Medial distal tibia guided growth with retrograde medial malleolus screw (see Chapter 8)—perform this in a skeletally immature child

ii. Distal tibia and fibula valgus-correction osteotomies (see Chapter 8)—perform this in a skeletally mature adolescent

iii. Resection and fat grafting of the physeal bar (if appropriate) with or without concurrent distal tibia and fibula valgus-correction osteotomies (see Chapter 8)—perform this in a skeletally immature child with a small physeal bar

iv. Completion of the distal tibial and fibula growth arrests (epiphysiodeses) with concurrent distal tibia and fibula valgus-correction osteotomies (see Chapter 8)—perform this in a skeletally immature child with a large, irresectable physeal bar

b. Once the ankle joint is anatomically aligned, correct the subtalar joint valgus according to the type of valgus present

i. Idiopathic flatfoot—calcaneal lengthening osteotomy (see Chapter 8)

ii. CVT (in the older child)—naviculectomy (see Chapter 8)

iii. COT (in the older child)—calcaneal lengthening osteotomy (see Chapter 8)

iv. Skewfoot—calcaneal lengthening osteotomy (see Chapter 8)

v. Tarsal coalition—calcaneal lengthening osteotomy (see Chapter 8)

vi. Congenital talocalcaneal valgus synostosis associated with fibula hemimelia, tibial hemimelia, lower extremity hemiatrophy, other syndromes and chromosome abnormalities—posterior calcaneus displacement osteotomy (see Chapter 8)

vii. Overcorrected clubfoot

• Translational—posterior calcaneus displacement osteotomy (see Chapter 8)

• Rotational—calcaneal lengthening osteotomy (see Chapter 8)

Cavovarus Foot (Excluding Those Due to Cerebral Palsy—See Below)

1. Definition—Deformity

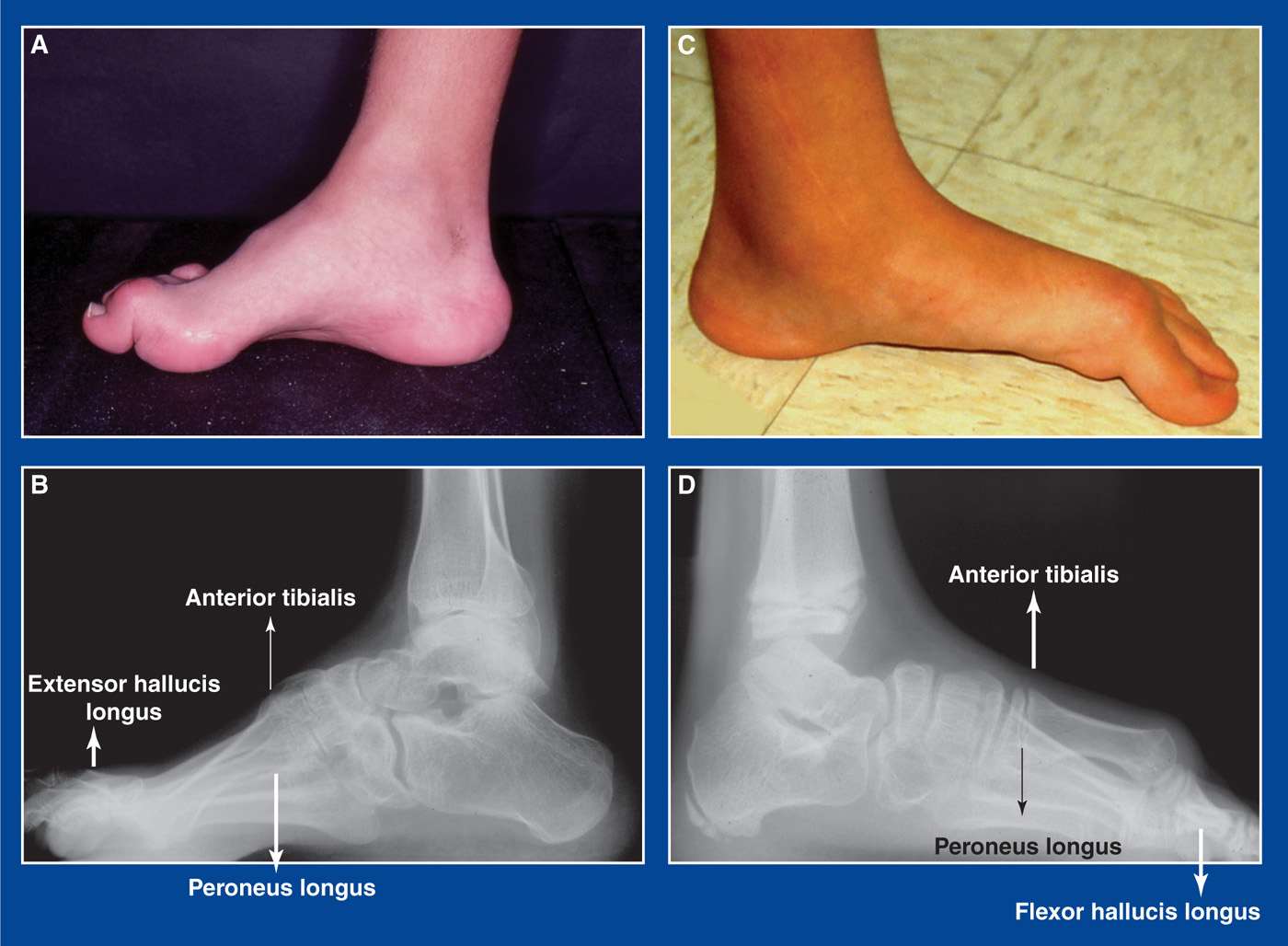

a. Acquired and usually progressive pronation deformity of the forefoot on the hindfoot that creates cavus deformity of the medial midfoot. There is secondary acquired and usually progressive varus/inversion deformity of the hindfoot. The ankle can be in dorsiflexion, plantar flexion, or neutral. It is the manifestation of a neuromuscular disorder, rather than a primary deformity, unless proven otherwise (Figure 5-5).

Figure 5-5. Cavovarus foot deformities in a young boy with CMT disease. A. Top/front view shows cavus with varus heels, visible medially. B. Side views show cavus of right foot and adductus of left foot. C. Posterior view shows varus heels and forefoot adductus.

2. Elucidation of the segmental deformities

a. Forefoot—pronated

b. Midfoot—adducted or neutral

c. Hindfoot—varus/inverted

d. Ankle—plantar flexed, neutral, or dorsiflexed

i. NOTE: It is uncommon for there to be contracture of the tendo-Achilles or the gastrocnemius in a cavovarus foot in a child with Charcot–Marie–Tooth (CMT) disease. The apparent ankle equinus (plantar flexion of the foot at the ankle) is, in fact, usually forefoot equinus, i.e., cavus (plantar flexion of the forefoot on the hindfoot) (see Assessment Principle #12, Figure 3-14, Chapter 3). The ankle is often hyperdorsiflexed with an exaggerated calcaneal pitch.

e. Tibia—external torsion

i. In most children with cavovarus foot deformities, regardless of the etiologic underlying neuromuscular disorder, there is coincident external tibial torsion (see Assessment Principle #7,Chapter 3).

f. Muscle imbalances (opposite those seen in dorsal bunion deformities) (Figure 5-6)

i. Weak anterior tibialis

ii. Strong peroneus longus

iii. Recruited and, therefore, stronger extensor hallucis longus (EHL) than flexor hallucis longus (FHL)

g. “Flexibility” classification for the forefoot and hindfoot (unpublished)

i. Flexible =

• dynamic deformity of the forefoot or hindfoot that corrects with tendon transfers

• dynamic and flexible deformity of the hindfoot that corrects following correction of the forefoot deformity and with tendon transfers

ii. Stiff = structural deformity of the forefoot or hindfoot that corrects with soft tissue releases

iii. Rigid = structural deformity of the forefoot or hindfoot that requires osteotomies and/or arthrodeses

h. Cavovarus Flexibility Classification System (Hindfoot–Forefoot) (unpublished)

i. Flexible–Flexible

ii. Stiff–Flexible

iii. Rigid–Flexible

iv. Rigid–Stiff

v. Rigid–Rigid

vi. Late Rigid–Rigid

Figure 5-6. A. Cavovarus foot. B. Cavovarus foot muscle imbalances: weak anterior tibialis, relatively stronger peroneus longus, recruited extensor hallucis longus to compensate for weak anterior tibialis. C. Dorsal bunion deformity. D. Dorsal bunion muscle imbalances: strong anterior tibialis, weak peroneus longus, recruited FHL to compensate for weak peroneus longus.

3. Imaging

a. Standing AP and lateral of foot (see Assessment Principle #18, Figures 3-20 and 3-22, Chapter 3)

b. Standing AP block x-ray with 2.5-cm block under lateral forefoot (4th and 5th MT heads) (see Assessment Principle #19, Figure 3-24, Chapter 3)

c. Standing AP, lateral, and mortis of ankle

d. Standing AP and lateral thoracolumbar spine

e. AP pelvis (in patients with CMT or suspected CMT)

4. Natural history

a. Progressive increase in the severity and rigidity of the segmental deformities with pain, gait instability, and skin pressure injuries (inflammation, callus formation, blistering, ulceration) under the 1st and 5th MT heads and at the base of the 5th MT (see Assessment Principle #9, Figure 3-5, Chapter 3).

5. Nonoperative treatment

a. Accommodative shoe wear with over-the-counter soft arch supports pending results of neuromuscular workup—then operate.

6. Operative indications

a. Pain, gait instability, skin pressure injuries, and/or progressive deformity

i. following completion of a neuromuscular workup, with treatment of the underlying condition if treatment exists

7. Operative treatment, based on the Cavovarus Flexibility Classification System, with reference to the surgical techniques section of the book for each individual procedure (see Management Principles #13, 15, 16, 22, 23-1, and 24, Chapter 4). NOTE: If a gastrocnemius recession or a tendo-Achilles lengthening is needed, it should be performed in the second stage of a 2-stage procedure (see Management Principle #23-2, Chapter 4).

a. Flexible–Flexible

i. Peroneus longus to peroneus brevis transfer (see Chapter 7)

ii. Posterior tibialis tendon lengthening—Z-lengthening or intramuscular recession (see Chapter 7)

b. Stiff–Flexible

i. Superficial plantar-medial release (see Chapter 7)

ii. Posterior tibialis tendon lengthening—Z-lengthening or intramuscular recession (see Chapter 7)

iii. Peroneus longus to peroneus brevis transfer (see Chapter 7)

iv. Percutaneous tenotomy of FHL and FDL to toes 2 to 5 (see Chapter 7)

c. Rigid–Flexible

i. Stage 1

• Superficial plantar-medial release (see Chapter 7)

• Posterior tibialis tendon lengthening—Z-lengthening or intramuscular recession (see Chapter 7)

• Percutaneous tenotomy of FHL and FDL to toes 2 to 5 (see Chapter 7)

ii. Stage 2—2 weeks later

• Medial cuneiform (dorsiflexion) plantar-based opening wedge osteotomy (see Chapter 8)

• Peroneus longus to peroneus brevis transfer (see Chapter 7)

• Possible posterior calcaneus lateral displacement osteotomy (see Chapter 8)

• Possible split anterior tibialis tendon transfer (see Chapter 7)

• Possible Jones transfer of extensor hallux longus to 1st MT neck with hallux interphalangeal (IP) joint tenodesis (see Chapter 7) or arthrodesis (see Chapter 8)

• Possible Hibbs transfer of extensor digitorum communis to peroneus tertius or cuboid (see Chapter 7)

d. Rigid–Stiff

i. Stage 1

• Deep plantar-medial release (see Chapter 7)

• Percutaneous tenotomy of FHL and FDL to toes 2 to 5 (see Chapter 7)

ii. Stage 2—2 weeks later

• Medial cuneiform (dorsiflexion) plantar-based opening wedge osteotomy (see Chapter 8)

• Peroneus longus to peroneus brevis transfer (see Chapter 7)

• Possible posterior calcaneus lateral displacement osteotomy (see Chapter 8)

• Possible split anterior tibialis tendon transfer (see Chapter 7)

• Possible Jones transfer of extensor hallux longus to 1st MT neck with hallux IP joint tenodesis (see Chapter 7) or arthrodesis (see Chapter 8)

• Possible Hibbs transfer of extensor digitorum communis to peroneus tertius or cuboid (see Chapter 7)

e. Rigid–Rigid

i. Stage 1

• Deep plantar-medial release (see Chapter 7)

• Percutaneous tenotomy of FHL and FDL to toes 2 to 5 (see Chapter 7)

ii. Stage 2—2 weeks later

• Medial cuneiform (dorsiflexion) plantar-based opening wedge osteotomy (see Chapter 8)

• Peroneus longus to peroneus brevis transfer (see Chapter 7)

• Posterior calcaneus lateral displacement osteotomy (see Chapter 8)

• Possible split anterior tibialis tendon transfer (see Chapter 7)

• Possible Jones transfer of extensor hallux longus to 1st MT neck with hallux IP joint tenodesis (see Chapter 7) or arthrodesis (see Chapter 8)

• Possible Hibbs transfer of extensor digitorum communis to peroneus tertius or cuboid (see Chapter 7)

f. Late Rigid–Rigid

i. Stage 1

• Deep plantar-medial release (see Chapter 7)

• Percutaneous tenotomy of FHL and FDL to toes 2 to 5 (see Chapter 7)

ii. Stage 2—2 weeks later or concurrent

• Midfoot wedge resection/arthrodesis (see Chapter 8)

• or, Triple arthrodesis (see Chapter 8 and Management Principle #13, Chapter 4)

• Possible split anterior tibialis tendon transfer (see Chapter 7)

• Possible Jones transfer of extensor hallux longus to 1st MT neck with hallux IP joint tenodesis (see Chapter 7) or arthrodesis (see Chapter 8)

• Possible Hibbs transfer of extensor digitorum communis to peroneus tertius or cuboid (see Chapter 7)

• Possible posterior tibialis tendon transfer through the interosseous membrane to the dorsum of the foot. Best indication is a strong posterior tibialis and no other functional muscle power (see Chapter 7)

Cavovarus Foot (Due to Cerebral Palsy)

1. Definition – Deformity

a. Acquired and progressive varus deformity of the hindfoot with secondary pronation of the forefoot on the hindfoot creating a cavus midfoot deformity. The ankle is plantar flexed, because there is always associated contracture of the gastrocnemius or the entire triceps surae. The deformities are the result of muscle imbalances due to the cerebral injury rather than being primary deformities. Cavovarus is most commonly seen in children with spastic hemiplegia (Figure 5-7).

2. Elucidation of the segmental deformities

a. Forefoot—pronated

b. Midfoot—adducted or neutral

c. Hindfoot—varus/inverted

d. Ankle—plantar flexed (equinus)

Figure 5-7. An 8-year-old girl with left hemiplegic cerebral palsy and with an equinocavovarus foot deformity.

e. Tibia—external torsion.

i. In most children with cavovarus foot deformities, including those with cerebral palsy, there is coincident external tibial torsion (see Assessment Principle #7, Chapter 3).

f. Muscle imbalances

i. Greater spasticity in the anterior tibialis and posterior tibialis than in the peroneal muscles

ii. Occasionally, the peroneus longus is overpowering the anterior tibialis

3. Imaging

a. Standing AP and lateral of foot (see Assessment Principle #18, Figures 3-20 and 3-22)

b. Standing AP block x-ray is not reliable in children with cerebral palsy, because the spastic inverters often do not relax sufficiently to allow the subtalar joint to evert (to reveal the true flexibility of the subtalar joint)

c. Standing AP, lateral, and mortis of ankle

4. Natural history

a. Progressive increase in the severity and rigidity of the segmental deformities with pain, gait instability, and skin pressure injuries (inflammation, callus formation, blistering, ulceration) at the base of the 5th MT, over the dorsolateral aspect of the talar head in the sinus tarsi region (related to rubbing in the AFO), and occasionally under the 1st MT head

5. Nonoperative treatment

a. Physical therapy—stretching

b. Bracing—AFO

c. Injection of botulinum toxin (BOTOX) into the most spastic muscles

d. Serial below-the-knee (short-leg) stretching casts

e. Tone-reducing medications, such as baclofen

6. Operative indications

a. Pain, gait instability, skin pressure injuries, and/or progressive deformity that are not controlled with nonoperative modalities

i. Ideally, in children over the age of 6 to 7 years

7. Operative treatment with reference to the surgical techniques section of the book for each individual procedure

a. Rancho procedure

i. Split anterior tibialis tendon transfer (see Chapter 7)

ii. Posterior tibialis tendon lengthening

iii. Strayer gastrocnemius recession (see Chapter 7)

• Rarely, if ever, a tendo-Achilles lengthening. The soleus is rarely contracted in children with cerebral palsy, and so a TAL should not be necessary. Overlengthening the tendo-Achilles results in a decrease/weakening of the ground reaction force and leads to lever arm dysfunction with an increased crouched gait (see Basic Principle #7, Figure 2-10, Chapter 2).

b. If rigid, severe forefoot pronation and hindfoot varus exist, those deformities must be corrected (see Management Principles #15, 16, and 22-2, Chapter 4) concurrent with muscle balancing procedures, as the latter will not correct the former (see Management Principles #15 and 22-2, Chapter 4).

i. If the hindfoot varus is flexible: superficial plantar-medial release (S-PMR) (see Chapter 7) plus posterior tibialis tendon lengthening—Z-lengthening or intramuscular recession (see Chapter 7)

ii. If the hindfoot varus is not flexible: Deep plantar-medial release (D-PMR) (see Chapter 7)

iii. If rigid forefoot pronation persists after S-PMR or D-PMR:

• Medial cuneiform (dorsiflexion) plantar-based opening wedge osteotomy (see Chapter 8)

• Peroneus longus to peroneus brevis transfer (see Chapter 7) rather than a split anterior tibialis tendon transfer, as the latter will potentiate the forefoot pronation in the face of a strong peroneus longus

Calcaneocavus (Transtarsal Cavus) Foot

1. Definition—Deformity

a. Plantar flexion of the entire forefoot on the hindfoot with hyperdorsiflexion of the hindfoot

i. due to muscle imbalance with weakness of the triceps surae, but preservation of strength in the posterior tibialis and peroneal muscles

ii. seen in some children with myelomeningocele, postpoliomyelitis, and other paralytic conditions (Figure 5-8)

2. Elucidation of the segmental deformities

a. Forefoot—plantar flexed

i. plantar flexion of the entire forefoot on the hindfoot, creating a transtarsal cavus

ii. MTs are parallel with each other in the sagittal plane.

b. Midfoot—neutral

c. Hindfoot—usually neutral with exaggerated calcaneal pitch

d. Ankle

i. Dorsiflexed

ii. often, valgus orientation

3. Imaging

a. Standing AP and lateral of foot

b. Standing AP, lateral, and mortis of ankle

c. Standing AP and lateral thoracolumbar spine

4. Natural history

a. Progressive increase in the severity and rigidity of the cavus deformity with increasing crouched gait along with pain and skin pressure injuries (inflammation, callus formation, blistering, ulceration) under the calcaneus and the MT heads as the weight-bearing pressures are concentrated under a progressively smaller plantar surface area

5. Nonoperative treatment

a. Tall arch support

6. Operative indications

a. Pain under the heel and/or the MT heads with weight-bearing (if the skin is sensate)

b. Ulceration, or skin at risk of ulceration, under the heel and/or the MT heads (if the skin is insensate)

Figure 5-8. Calcaneocavus foot deformity in a teenager with S1 level myelomeningocele. A. Medial photo of foot shows exaggerated arch height across the entire midfoot. Though not visible in this photo, the hindfoot/subtalar joint is in neutral alignment. The soft tissues under the MT heads and the calcaneus are thick and callused. B. Standing lateral radiograph shows transtarsal cavus with relative parallelism of all MTs. In a cavovarus foot by contrast, the 1st MT would be hyperplantar flexed in relation to the 5th MT (Figure 3-25). The calcaneus, in this foot, is hyperdorsiflexed.

7. Operative treatment with reference to the surgical techniques section of the book for each individual procedure

a. Posterior calcaneus dorsal and posterior displacement osteotomy (see Chapter 8)

i. with plantar fasciotomy (see Chapter 7)

ii. with possible anterior tibialis tendon lengthening

b. Midfoot wedge resection/arthrodesis—perform this for the most severe and rigid cases (see Chapter 8)

Congenital Clubfoot (Talipes Equinovarus)

1. Definition—Deformity

a. Congenital cavus, adductus, varus, and equinus deformities that are not passively correctable (Figure 5-9)

b. Most are idiopathic, though some are associated with myelomeningocele, arthrogryposis, and other syndromes and disorders.

Figure 5-9. A. An infant with congenital clubfeet with the obvious deformities of cavus, adductus, varus/inversion, and equinus. (From Mosca VS. The Foot. In: Morrissy RT, Weinstein SL, eds. Lovell and Winter’s Pediatric Orthopaedics. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2001:1153, Figure 29-1.) B. AP radiograph shows the severe inversion and adductus. C. Lateral radiograph shows the severe equinus, cavus, and adductus. The hindfoot is pointing to the left and the forefoot is pointing to the right.

2. Elucidation of the segmental deformities

a. Forefoot—pronated

b. Midfoot—adducted

c. Hindfoot—varus/inverted

d. Ankle—plantar flexed (equinus)

3. Imaging

a. Not necessary for diagnosis

b. Maximum dorsiflexion/abduction/eversion AP and lateral of foot (see Figure 5-9)—indicated to:

i. confirm residual deformities preoperatively after failing nonoperative treatment

ii. confirm apparent or obvious recurrent deformities after nonoperative or operative treatment, particularly when contemplating further nonoperative or operative treatment

iii. confirm deformity correction following operative treatment

c. Hip screening imaging for idiopathic clubfoot is not indicated—no documented association of the two deformities

4. Natural history

a. Persistence of deformity with pain, functional disability, and inability to wear normal shoes

5. Nonoperative treatment

a. Ponseti method of serial manipulation and long-leg casting, along with percutaneous Achilles tenotomy in most cases (well described in Clubfoot: Ponseti Management, LT Staheli, editor. www.Global-HELP.org monograph)

i. It should be successful in at least 85% of idiopathic cases.

ii. It should be successful in a smaller percentage of nonidiopathic (arthrogryposis, myelomeningocele) cases, but definitely worth the effort.

6. Operative indications

a. Failure to achieve full deformity correction with nonoperative treatment

7. Operative treatment with reference to the surgical techniques section of the book for each individual procedure

a. Percutaneous tendo-Achilles tenotomy (see Chapter 7)—perform this when there is less than 10° of ankle dorsiflexion after the cavus, adductus, and varus have been fully corrected with serial casting in an infant or very young child

i. This is a complete tenotomy, not a lengthening.

ii. It should be performed when there is little (or no) expectation that a posterior ankle capsulotomy will be required, which is the assumption in most babies up to at least 2 years of age.

• If a percutaneous tendo-Achilles tenotomy is concurrently converted to an open ankle capsulotomy, the gap in the tendon may not heal and remodel as well, and with as good preservation of excursion, as with percutaneous Achilles tenotomy alone.

iii. If the need for a posterior capsulotomy is anticipated, an open tendo-Achilles lengthening should be performed. If a capsulotomy is then deemed unnecessary, there is no measureable disability from having performed a formal tendo-Achilles lengthening.

b. Posterior release (see Chapter 7)—perform this in an older child in whom there is less than 10° of dorsiflexion after the cavus, adductus, and varus have been fully corrected with serial casting and in whom there is less than 10° of dorsiflexion after TAL

c. À la carte partial-to-complete circumferential release (see Chapter 7)—perform this if there are residual cavus, adductus, and/or varus deformities in addition to an equinus deformity

i. The McKay procedure is the surgical analog of the Ponseti method, in that it embraces the pathoanatomy ascribed to by Ponseti.

ii. In non- idiopathic clubfoot (myelomeningocele, arthrogryposis), the tendons are released rather than lengthened, because of the very high recurrence rate in these feet.

Figure 5-10. Untreated clubfeet in a 2-year-old boy who was adopted from a developing country by parents in the United States.

1. Definition—Deformity

a. Untreated congenital equino-cavo-adducto-varus in an older child or adolescent (Figures 5-10 and 5-11)

2. Elucidation of the segmental deformities

a. Forefoot—pronated

b. Midfoot—adducted

c. Hindfoot—varus/inverted

d. Ankle—plantar flexed (equinus)

3. Imaging

a. Standing AP and lateral of foot

b. Standing AP and lateral of ankle

4. Natural history

a. Persistence of deformity with pain, functional disability, and inability to wear normal shoes

5. Nonoperative treatment

a. Ponseti method of serial manipulation and long-leg casting, along with percutaneous Achilles tenotomy in most cases (well described in Clubfoot: Ponseti Management, LT Staheli, editor. www.Global-HELP.org monograph), starting in children up to at least 5 to 6 years of age (and possibly older)

i. Should be successful less often than when initiated in infants, with the rate of success inversely proportional to age at initiation

6. Operative indications

a. Failure or age-inappropriateness of serial casting to correct one or more of the clubfoot segmental deformities

b. Pain, shoe-fitting difficulties, dysfunction

Figure 5-11. Neglected clubfeet in an 18-year-old immigrant to the United States. The natural history of clubfoot is clear: persistence of deformities, inability to wear shoes, ostracism, poverty, and eventual pain.

7. Operative treatment with reference to the surgical techniques section of the book for each individual procedure

a. Percutaneous tendo-Achilles tenotomy (see Chapter 7)—perform this when there is less than 10° of ankle dorsiflexion after the cavus, adductus, and varus have been fully corrected with serial casting in a young child

i. This is a complete tenotomy, not a lengthening.

ii. It should be performed when there is little (or no) expectation that a posterior ankle capsulotomy will be required.

• If a percutaneous tendo-Achilles tenotomy is concurrently converted to an open ankle capsulotomy, the gap in the tendon may not heal and remodel as well, and with as good preservation of excursion, as with percutaneous Achilles tenotomy alone.

iii. If the need for a posterior capsulotomy is anticipated, an open tendo-Achilles lengthening should be performed. If a capsulotomy is then deemed unnecessary, there is no measureable disability from having performed a formal tendo-Achilles lengthening.

b. Posterior release (see Chapter 7)—perform this if there is less than 10° of dorsiflexion after the cavus, adductus, and varus have been fully corrected with serial casting and the tendo-Achilles has been lengthened

c. À la carte partial-to-complete circumferential release (see Chapter 7)—perform this if there are residual cavus, adductus, and/or varus deformities in addition to an equinus deformity

i. The McKay procedure is the surgical analog of the Ponseti method, in that it embraces the pathoanatomy ascribed to by Ponseti.

ii. In non- idiopathic clubfoot, the tendons are released rather than lengthened, because of the high recurrence rate in these feet.

d. À la carte partial-to-complete circumferential release (see Chapter 7) along with one or more of the following procedures—perform one or more of these additional procedures if there are residual cavus, adductus, and/or varus deformities in addition to an equinus deformity, and structural metatarsus adductus (MA), fixed hindfoot varus with a long lateral column of the foot, and/or muscle imbalance

i. Medial column lengthening for structural MA

• Medial cuneiform opening wedge osteotomy (see Chapter 8)

ii. Lateral column shortening for structural MA (see Management Principle #18, Chapter 4)

• Closing wedge osteotomy of the cuboid (see Chapter 8)

iii. Lateral column shortening for resistant hindfoot varus/inversion with a long lateral column of the foot (see Management Principle #18, Chapter 4)

• Calcaneocuboid resection/fusion (see Chapter 8)

• Lichtblau resection of the anterior calcaneus (see Chapter 8)

• Closing wedge osteotomy of the anterior calcaneus (see Chapter 8)

iv. Posterior calcaneus lateral displacement osteotomy (see Chapter 8)

v. Anterior tibialis tendon transfer to lateral (3rd) cuneiform (see Chapter 7)

e. Triple arthrodesis (see Chapter 8)—perform this if there are no other options for correcting the deformities because of severity and/or rigidity, or because of existing degenerative arthritis of the subtalar joint (see Management Principle #13, Chapter 4)

f. Gradual deformity correction with external fixation (not elucidated in this book)

Severe, Rigid, Resistant Arthrogrypotic Clubfoot in an Infant or Young Child

1. Definition—Deformity

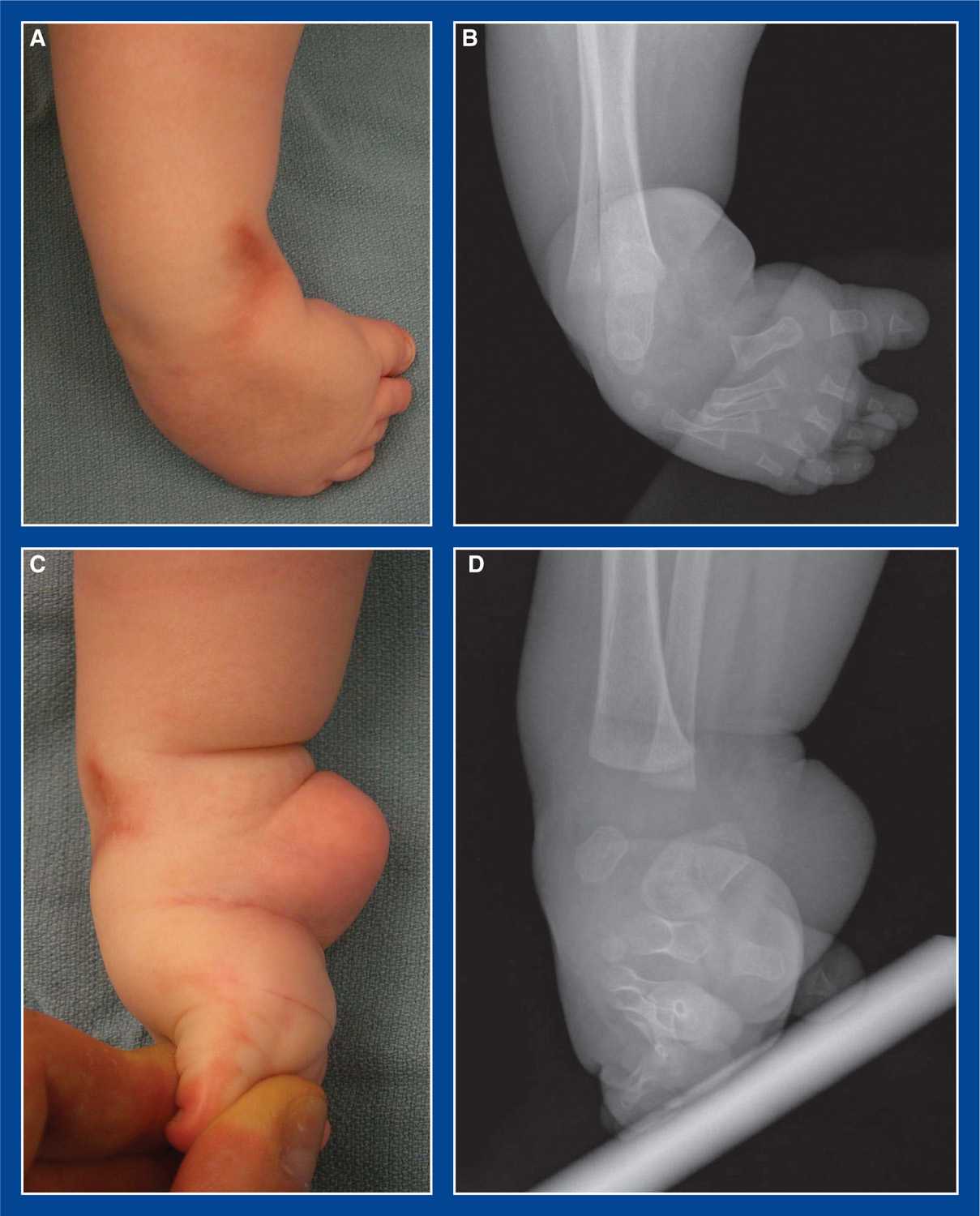

a. Severe, rigid, resistant congenital clubfoot in an infant with arthrogryposis (Figure 5-12)

b. More flexible congenital clubfoot deformities in infants with arthrogryposis should be treated exactly like idiopathic congenital clubfoot (see this chapter).

2. Elucidation of the segmental deformities

a. Forefoot—pronated

b. Midfoot—adducted

c. Hindfoot—varus/inverted

d. Ankle—plantar flexed (equinus)

3. Imaging

a. Maximum dorsiflexion/abduction/eversion AP and lateral of foot—indicated to:

i. confirm residual deformities preoperatively after failing nonoperative treatment

4. Natural history

a. Persistence of deformity with pain, functional disability, and inability to wear normal shoes

5. Nonoperative treatment

a. Ponseti method of serial manipulation and long-leg casting

6. Operative indications

a. Little (or no) improvement in the severe, rigid clubfoot deformities in an infant with arthrogryposis after a long series of casts, with the presumption that it would be challenging to stretch the posterior ankle skin and align the foot in the ankle mortis even if a talectomy were performed (Figure 5-12).

i. The expectation is that, following surgery, the deformities will be improved (Figure 5-13) and serial casting will be reinitiated. The deformities might then be corrected with further serial casting or improved enough with further serial casting that conventional á la carte partial-to-complete circumferential release will be successful.

Figure 5-12. Severe, rigid, resistant arthrogrypotic clubfoot. A–D after 14 casts: A. Top photo. B. AP x-ray. C. Medial photo with maximum dorsiflexion. D. Lateral x-ray with maximum dorsiflexion.

7. Operative treatment with reference to the surgical techniques section of the book for each individual procedure

a. Limited, minimally invasive soft tissue releases for clubfoot (see Chapter 7), as an incidental event to enable more effective ongoing serial casting (Figure 5-13)

i. Percutaneous tendo-Achilles tenotomy

ii. Limited open plantar fasciotomy

iii. Limited open posterior tibialis tenotomy

iv. Percutaneous tenotomies of FHL and FDL to toes 2-to 5

b. Talectomy—perform this for failure of “a” (see Chapter 8)

Figure 5-13. A. One week after percutaneous tenotomies of tendo-Achilles and long toe flexors, as well as mini-open plantar fasciotomy and posterior tibialis tenotomy in the foot in Figure 5-12. B to E after four more casts: B. Simulated standing top photo. C. Simulated standing AP x-ray. D. Medial photo with maximum dorsiflexion. E. Lateral x-ray with maximum dorsiflexion. F to H one year later, following two serial casts for minor recurrence: F. Standing top photo. G. Medial photo with maximum dorsiflexion. H. Lateral x-ray with maximum dorsiflexion.

Corrected Congenital Clubfoot (Talipes Equinovarus) with Anterior Tibialis Overpull

1. Definition—Deformity

a. Structurally corrected clubfoot with stronger anterior tibialis than peroneus tertius and relatively weak peroneus longus resulting in a dynamic supination deformity of the foot (Figure 5-14)

2. Elucidation of the segmental deformities

a. None

3. Imaging

a. Standing AP and lateral of foot

i. to confirm full correction of deformities

ii. to ensure adequate size of the ossification center of the lateral (3rd) cuneiform to accept the anterior tibialis tendon

4. Natural history

a. Instability of gait with frequent inversion injuries

b. Pain and exaggerated callus formation along the plantar–lateral border of the foot

5. Nonoperative treatment

a. Peroneus tertius strengthening exercises. Efficacy is not documented.

b. Serial casting to correct any residual or recurrent deformities prior to tendon transfer surgery.

6. Operative indications

a. Exaggerated dynamic supination of a well-corrected and flexible clubfoot during the swing phase of the gait cycle

i. that creates instability of gait and/or excessive weight-bearing on the plantar–lateral aspect of the foot

ii. after failure of strengthening exercises to balance the strength of the anterior tibialis and peroneus tertius muscles

iii. in which there is a large ossification center of the lateral (3rd) cuneiform

Figure 5-14. Assess muscle balance in a clubfoot by asking the child to dorsiflex the foot, or by stimulating the plantar aspect of the foot. A. Normal muscle balance between the anterior tibialis and the peroneus tertius. The plane of the MT heads is perpendicular to the tibial shaft. B. Relative overpull of normal anterior tibialis vs. weak peroneus tertius and longus in a child with a clubfoot that has excellent deformity correction and flexibility. The plane of the MT heads is supinated in relation to the tibial shaft.

7. Operative treatment with reference to the surgical techniques section of the book for each individual procedure

a. Anterior tibialis tendon transfer to lateral (3rd) cuneiform (see Chapter 7)

Recurrent/Persistent Clubfoot Deformity

1. Definition—Deformity

a. Recurrence or persistence of one or more of the clubfoot segmental deformities following nonoperative or operative initial treatment (Figure 5-15).

2. Elucidation of the segmental deformities

a. Forefoot—pronated

b. Midfoot—adducted

c. Hindfoot—varus/inverted

d. Ankle—plantar flexed (equinus)

3. Imaging

a. Maximum dorsiflexion/abduction/eversion AP and lateral of foot—for younger children

b. Standing AP and lateral of foot—for older children

c. AP, lateral, mortis of ankle

4. Natural history

a. Persistence of deformity with pain, functional disability, and inability to wear normal shoes

5. Nonoperative treatment

a. Ponseti method of serial manipulation and long-leg casting, along with percutaneous Achilles tenotomy in most cases (well described in Clubfoot: Ponseti Management, LT Staheli, editor. www.Global-HELP.org monograph), starting in children up to at least 5 to 6 years of age (and possibly older)

i. Should be successful less often than when initiated in infants, with the rate of success inversely proportional to age at initiation

6. Operative indications

a. Failure or age-inappropriateness of serial casting to correct one or more of the clubfoot segmental deformities

b. Pain, shoe-fitting difficulties, dysfunction

7. Operative treatment with reference to the surgical techniques section of the book for each individual procedure

a. Percutaneous tendo-Achilles tenotomy (see Chapter 7)—perform this when there is less than 10° of ankle dorsiflexion after the cavus, adductus, and varus have been fully corrected with serial casting in an infant or very young child

i. This is a complete tenotomy, not a lengthening.

ii. It should be performed when there is little (or no) expectation that a posterior ankle capsulotomy will be required, which is the assumption in most babies up to at least 2 years of age.

• If a percutaneous tendo-Achilles tenotomy is concurrently converted to an open ankle capsulotomy, the gap in the tendon will not heal and remodel as well, and with as good preservation of excursion, as occurs with percutaneous Achilles tenotomy alone.

iii. If the need for a posterior capsulotomy is anticipated, an open tendo-Achilles lengthening should be performed. If a capsulotomy is then deemed unnecessary, there is no measureable disability from having performed a formal tendo-Achilles lengthening.

Figure 5-15. Left clubfoot in a 10-month-old boy who was treated from birth with serial casting. He apparently achieved full correction of all segmental deformities, but was lost to follow-up and returned with recurrence of all segmental deformities. A. Foot at rest. B. Maximum passive dosiflexion and eversion.

b. Posterior release (see Chapter 7)—perform this if there are less than 10° of dorsiflexion after the cavus, adductus, and varus have been fully corrected with serial casting in an older child, particularly if there is suspicion that the posterior ankle joint capsule is contracted in addition to the tendo-Achilles

c. À la carte partial-to-complete circumferential release (see Chapter 7)—perform this if there are residual cavus, adductus, and/or varus deformities in addition to an equinus deformity

i. The McKay procedure is the surgical analog of the Ponseti method in that it embraces the pathoanatomy ascribed to by Ponseti

ii. In non-idiopathic clubfoot, the tendons are released rather than lengthened, because of the high recurrence rate in these feet

d. À la carte partial-to-complete circumferential release (see Chapter 7) along with one or more of the following procedures—perform one or more of these additional procedures if there are residual cavus, adductus, and/or varus deformities in addition to an equinus deformity, and structural MA, resistant hindfoot varus with a long lateral column of the foot, and/or muscle imbalance

i. Medial column lengthening for structural MA

• Medial cuneiform opening wedge osteotomy (see Chapter 8)

ii. Lateral column shortening for structural MA (see Management Principle #18, Chapter 4)

• Closing wedge osteotomy of the cuboid (see Chapter 8)

iii. Lateral column shortening for resistant hindfoot varus/inversion with a long lateral column of the foot (see Management Principle #18, Chapter 4)

• Calcaneocuboid resection/fusion (see Chapter 8)

• Lichtblau resection of the anterior calcaneus (see Chapter 8)

• Closing wedge osteotomy of the anterior calcaneus (see Chapter 8)

iv. Posterior calcaneus lateral displacement osteotomy (see Chapter 8)

v. Anterior tibialis tendon transfer to lateral (3rd) cuneiform (see Chapter 7)

e. Triple arthrodesis (see Chapter 8)—perform this if there are no other options for correcting the deformities because of severity and/or rigidity, or because of existing degenerative arthritis of the subtalar joint (see Management Principle #13, Chapter 4)

f. Gradual deformity correction with external fixation (not elucidated in this book)

Rotational Valgus Overcorrection of the Subtalar Joint

1. Definition—Deformity

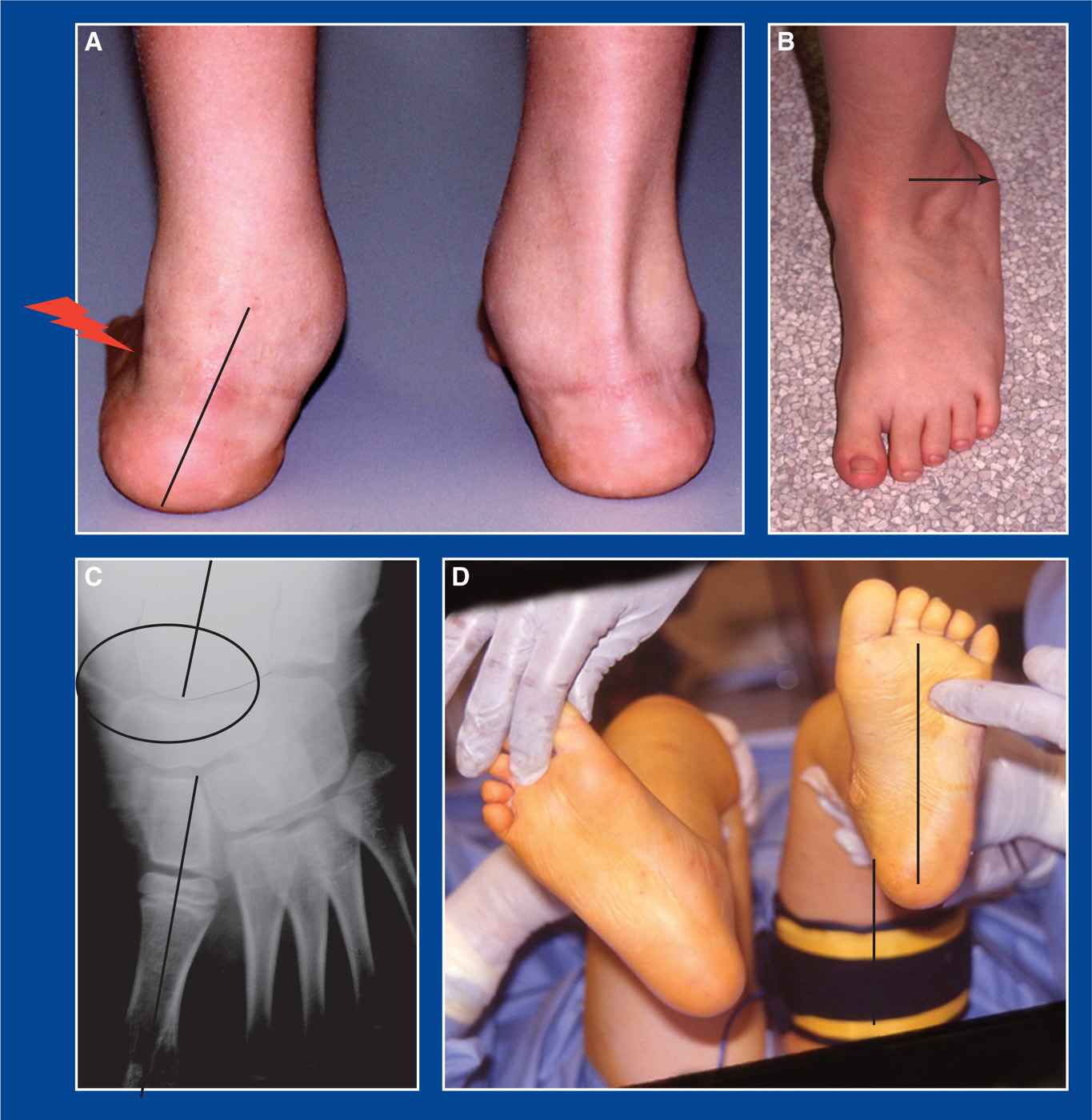

a. Iatrogenically acquired flatfoot in an operatively treated clubfoot with excessive external rotation of the subtalar joint (Figure 5-16)

i. due to excessive release of the subtalar joint, but without release of the talocalcaneal interosseous ligament

ii. with all components of eversion of the subtalar joint. Essentially, an acquired “physiologic” flatfoot

Figure 5-16. Previously operated clubfoot with rotational valgus overcorrection of the subtalar joint. A. Posterior view of severe valgus deformity of the hindfoot, similar to that seen in translational valgus overcorrection of the subtalar joint (see Figure 5-17A). B. Standing top image showing external rotation of the foot. Pain is typically experienced under the medial midfoot (similar to a flexible flatfoot with a tight tendo-Achilles), and there is often impingement-type pain in the sinus tarsi area or between the calcaneus and the lateral malleolus. C. Eversion of the subtalar joint is evident, with the navicular laterally positioned on the head of the talus. The abducted foot-CORA (see Assessment Principle #18, Figure 3-19, Chapter 3) is in the talar head-neck, as in an idiopathic flexible flatfoot. D. Example of an outward (positive) thigh–foot angle, as seen in this deformity.

2. Elucidation of the segmental deformities

a. Forefoot—supinated

b. Midfoot—neutral, abducted, or adducted

c. Hindfoot—valgus/everted

i. Positive thigh–foot angle

d. Ankle—plantar flexed (equinus)

e. Looks like an idiopathic flatfoot, clinically and radiographically

3. Imaging

a. Standing AP, lateral, Harris view of foot

b. AP, lateral, and mortis of ankle

4. Natural history

a. Persistence of deformity with pain under the medial midfoot and/or in the sinus tarsi area and/or in the lateral hindfoot—in some cases

5. Nonoperative treatment

a. Over-the-counter soft arch support or gel cushion insert

b. Accommodative shoe

6. Operative indications

a. Activity-related pain under the medial midfoot and/or in the sinus tarsi area and/or in the lateral hindfoot that is not relieved with prolonged attempts at nonoperative treatment

7. Operative treatment with reference to the surgical techniques section of the book for each individual procedure

a. Calcaneal lengthening osteotomy (see Chapter 8)

i. with possible tendo-Achilles lengthening (see Chapter 7) or gastrocnemius recession (see Chapter 7)

ii. with possible medial cuneiform plantar-based closing wedge (or dorsal opening wedge) osteotomy (see Chapter 8)

b. If there is coexisting ankle valgus (often present), correct the ankle valgus first (see Management Principle #23-6, Chapter 4), either by guided growth (see Medial Distal Tibia Guided Growth with Retrograde Medial Malleolus Screw, Chapter 8) or by distal tibia and fibula osteotomies (see Chapter 8)

Translational Valgus Overcorrection of the Subtalar Joint

1. Definition—Deformity

a. Iatrogenically acquired flatfoot in an operatively treated clubfoot with excessive lateral translation of the calcaneus under the talus (Figure 5-17)

Figure 5-17. Previously operated clubfoot with translational valgus overcorrection of the subtalar joint. A. Posterior view of severe valgus deformity of the hindfoot, similar to that seen in rotational valgus overcorrection of the subtalar joint (see Figure 5-16A). Impingement-type pain is typically experienced between the calcaneus and the lateral malleolus. B. Standing top image of the foot showing lateral translation of the heel (black arrow). C. The talonavicular joint is well-aligned (black oval). The talus and 1st MT are parallel, but can have a foot-CORA (see Assessment Principle #18, Figure 3-18, Chapter 3) in the talar head that is usually abducted less than 12°. D. Example of a neutral thigh-foot angle, as seen in this deformity.

i. due to excessive release of the subtalar joint with release of the talocalcaneal interosseous ligament

ii. often, with acceptable alignment at the talonavicular joint

2. Elucidation of the segmental deformities

a. Forefoot—neutral or supinated

b. Midfoot—neutral, abducted, or adducted

c. Hindfoot—valgus without eversion, i.e., with well-aligned talonavicular joint

i. Neutral thigh–foot angle

d. Ankle—neutral or plantar flexed (equinus)

e. Looks somewhat like an idiopathic flatfoot clinically, but not radiographically

3. Imaging

a. Standing AP, lateral, Harris view of foot

b. AP, lateral, and mortis of ankle

4. Natural history

a. Persistence of deformity with pain in the lateral hindfoot and/or in the sinus tarsi and occasionally under the medial midfoot—in some cases

5. Nonoperative treatment

a. Over-the-counter soft arch support or gel cushion insert

b. Accommodative shoe

6. Operative indications

a. Activity-related pain in the lateral hindfoot and/or in the sinus tarsi and occasionally under the medial midfoot that is not relieved with prolonged attempts at nonoperative treatment

7. Operative treatment with reference to the surgical techniques section of the book for each individual procedure

a. Posterior calcaneus medial displacement ± medial closing wedge osteotomy (see Chapter 8)

i. with possible tendo-Achilles lengthening (see Chapter 7) or gastrocnemius recession (see Chapter 7)

ii. with possible medial cuneiform plantar-based closing wedge (or dorsal opening wedge) osteotomy (see Chapter 8)

b. If there is coexisting ankle valgus (often present), correct the ankle valgus first (see Management Principle #23-6, Chapter 4), either by guided growth (see Medial Distal Tibia Guided Growth with Retrograde Medial Malleolus Screw, Chapter 8) or by distal tibia and fibula osteotomies (see Chapter 8)

Dorsal Subluxation/Dislocation of the Talonavicular Joint

1. Definition—Deformity

a. Iatrogenically acquired dorsal subluxation or dislocation of the navicular on the head of the talus in an operatively treated clubfoot (Figure 5-18)

i. due to overly extensive release of the talonavicular joint, usually with failure to release a contracted plantar fascia

2. Elucidation of the segmental deformities

a. Forefoot—pronated, neutral, or supinated

b. Midfoot—dorsal, and often lateral, subluxation or dislocation of the navicular on the head of the talus with appearance of cavus

c. Hindfoot—neutral, varus, or valgus

d. Ankle—neutral, plantar flexed (equinus), or dorsiflexed (calcaneus)

Figure 5-18. Previously operated clubfoot with dorsal subluxation of the talonavicular joint. A. Clinical image shows a tall instep (cavus) and short toe-to-heel length. B. Lateral radiograph shows dorsal subluxation of the navicular on the head of the talus and exaggerated plantar flexion of the first ray, including the MT, cuneiform, and navicular.

3. Imaging

a. Standing AP, lateral, oblique of foot

b. Consider CT scan of the foot and ankle in all three planes and with 3D reconstruction in older children and adolescents

4. Natural history

a. Persistence of deformity with pain over the dorsum of the midfoot and/or shoe-fitting problems related to the tall instep and relatively short toe-to-heel length of the foot—in some cases

5. Nonoperative treatment

a. Accommodative shoe

6. Operative indications

a. Pain over the dorsum of the midfoot and/or shoe-fitting problems related to the tall instep and relatively short toe-to-heel length of the foot.

b. Painful anterior ankle impingement between the navicular and the anterior distal tibial epiphysis

7. Operative treatment with reference to the surgical techniques section of the book for each individual procedure

a. 3rd street procedure (see Chapter 7)—perform this in children up to around age 6 years

b. Talonavicular joint arthrodesis—perform this in older children and adolescents

c. Resection of impinging portion of dorsally subluxated navicular (see Chapter 8)—perform this for isolated painful anterior ankle impingement in an older child or adolescent

d. Triple arthrodesis (see Chapter 8)—perform this in an older child or adolescent if the subluxation/dislocation is associated with severe deformities and degenerative arthritis of the other joints of the subtalar complex

Figure 5-19. Postsurgical clubfoot in a 15-year-old girl with anterior ankle impingement pain. A. Flattop talus with shallow/absent dorsal talar neck concavity (and small heterotopic ossicle) causing anterior ankle impingement and pain. B. Sagittal CT scan image confirming the pathology.

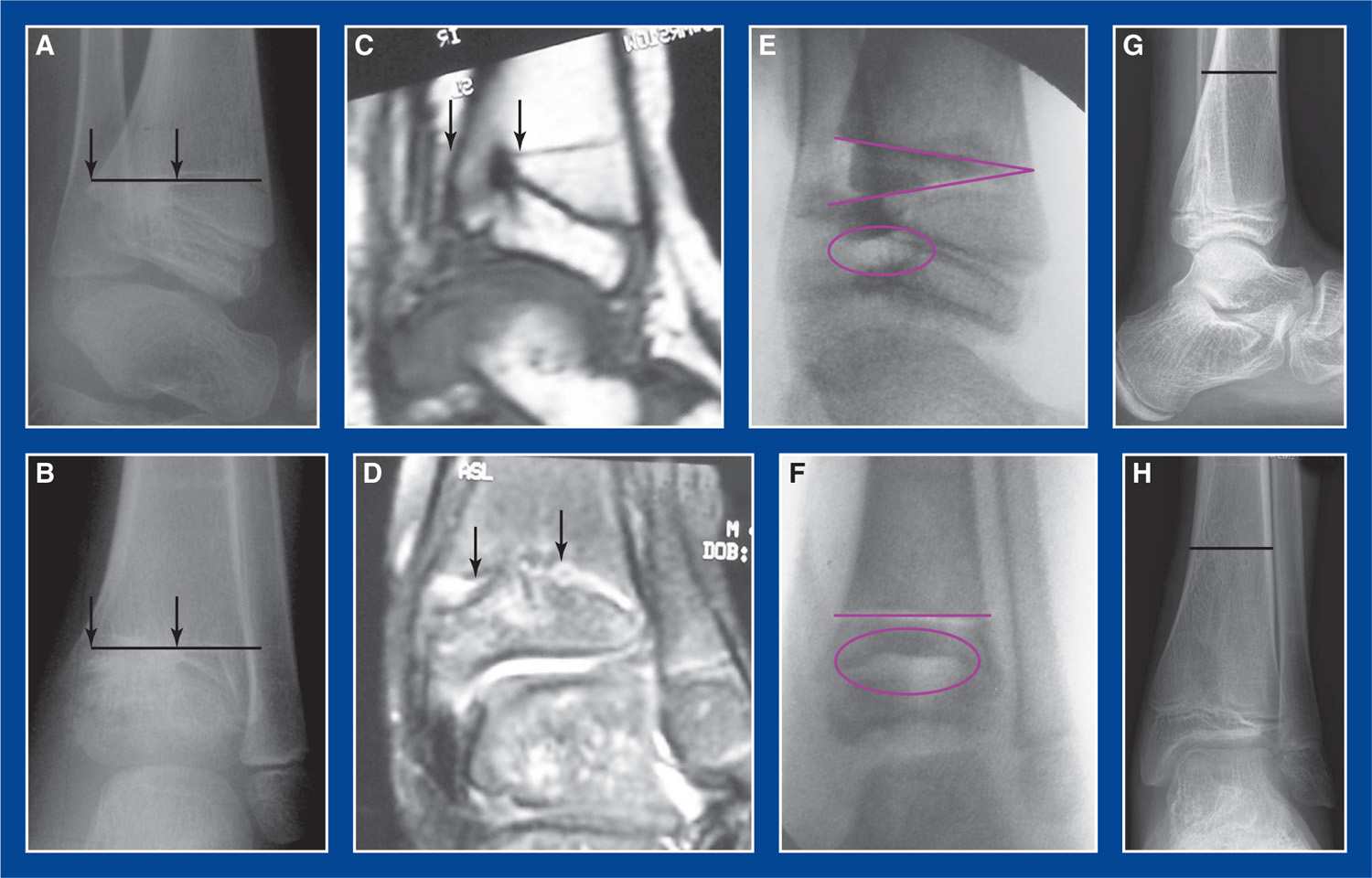

1. Definition—Deformity

a. Iatrogenically acquired impingement between the dorsal talar neck (or the navicular) and the anterior distal tibial epiphysis that limits dorsiflexion

i. Causes include:

• iatrogenic flattop talus from casting-induced and/or surgery-related crush injury to the dome of the talus (Figure 5-19)

• iatrogenic flattop talus from surgery-related avascular necrosis (Figure 5-20)

• iatrogenic posterior distal tibial growth arrest with progressive procurvatum deformity and flexion mal-orientation of the ankle joint (Figure 5-21)

• iatrogenic dorsal subluxation of the talonavicular joint (see Dorsal Subluxation/Dislocation of the Talonavicular Joint, above)

Figure 5-20. Avascular necrosis of the talus after clubfoot surgery with anterior impingement-type pain due to flattening of the dome and neck of the talus.

2. Elucidation of the segmental deformities

a. Flattop talar dome with shallow or flat dorsal neck of talus

b. Or, rarely, procurvatum deformity of distal tibia with flexion mal-orientation of the ankle joint

c. Or, dorsal subluxation of the navicular on the head of the talus

3. Imaging

a. Standing AP and lateral of foot

b. Standing AP, lateral, and mortis of ankle

c. CT scan of foot and ankle in all three planes and with 3D reconstruction in older children and adolescents

4. Natural history

a. Persistence or progression of deformity with anterior ankle pain that is exacerbated by dorsiflexion of the ankle—in some cases

5. Nonoperative treatment

a. High heel shoes

b. Heel wedge orthotics

6. Operative indications

a. Failure of nonoperative treatment to relieve the anterior ankle impingement-type pain that is exacerbated by dorsiflexion of the ankle.

7. Operative treatment with reference to the surgical techniques section of the book for each individual procedure

a. Debridement/reshaping of dorsal talar neck (see Chapter 8)—perform this if there is a dorsally prominent talar neck and a relatively normally shaped talar dome in a skeletally mature adolescent (see Figure 5-19)

b. Anterior distal tibia and fibula closing wedge/posterior translational dorsiflexion osteotomies (see Chapter 8)—perform this in a skeletally mature adolescent with a flat talar dome

c. Anterior distal tibia guided growth with anterior plate–screw construct to orient the joint into recurvatum (see Chapter 8)—perform this in a skeletally immature child with a flat talar dome

d. Posterior distal tibial physeal bar resection with fat grafting and concurrent posterior distal tibial opening wedge osteotomy (see above)

e. Do not lengthen tendo-Achilles! It will only increase the impingement.

Figure 5-21. Postsurgical clubfoot in a 5-year-old boy who had progressive loss of dorsiflexion and accompanying anterior ankle impingement-type pain. A. Lateral radiograph shows large posterior arrest of distal tibial physis, between arrow heads. Black line is Park–Harris growth arrest line. Resultant procurvatum deformity of the distal tibia created secondary anterior ankle impingement, despite normal anatomy of the talus. B. AP radiograph shows the arrest, roughly between the arrow heads. C. Sagittal MRI scan image shows the large, solid posterior physeal bar, between arrow heads. D. Coronal MRI scan image of the pathology. E. Lateral radiograph immediately after resection and fat grafting of the physeal bar (purple oval) and concurrent posterior distal tibia opening wedge osteotomy (purple wedge). F. AP image of the same.G. and H. Lateral and AP images 9 years later showing black Park–Harris line parallel with, and far from, the physis. The normal sagittal 10° extension tilt of the distal tibial articular surface has been restored.

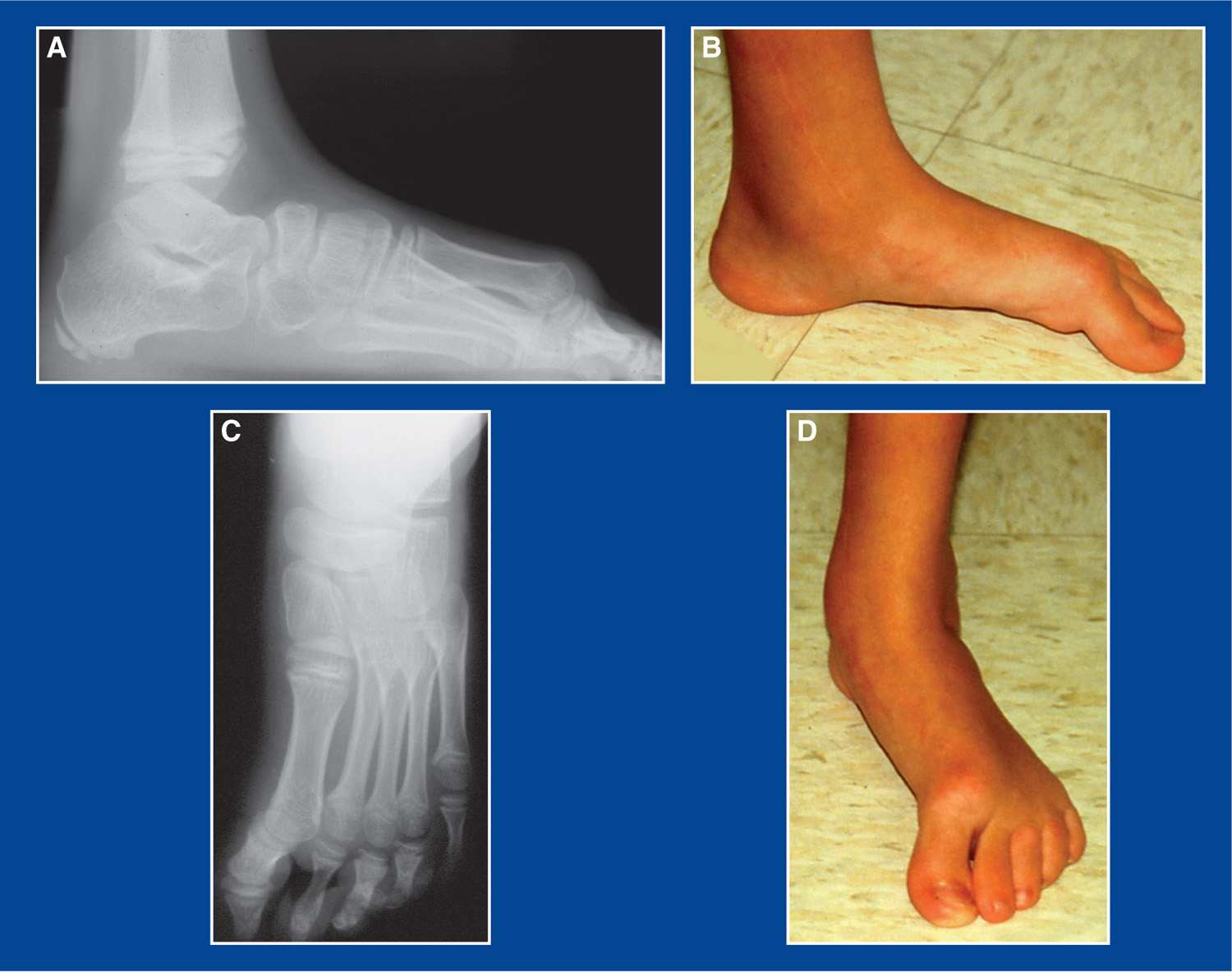

1. Definition—Deformity

a. Dorsal prominence of the distal end of the 1st MT associated with dorsiflexion of the medial (1st) ray of the forefoot and hyperplantar flexion of the hallux at the 1st metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joint (Figure 5-22)

i. Iatrogenic, usually following surgical treatment of clubfoot deformity

ii. Occasionally seen in a child with severe spastic quadriplegia as the result of primary muscle imbalance or after surgical treatment

2. Elucidation of the segmental deformities

a. Forefoot—supinated

i. Dorsiflexed medial (1st) ray of the forefoot—flexible or rigid

ii. Hyper-plantar flexed hallux at 1st MTP joint—flexible or fixed

b. Midfoot—neutral, abducted, or adducted

c. Hindfoot—neutral or valgus (laterally translated)

i. Stiff or rigid

ii. with good or fairly good alignment at the talonavicular joint

d. Muscle imbalances (opposite those seen in cavovarus foot deformities) (see Cavovarus Foot, Figure 5-6, this chapter)

i. Strong anterior tibialis

ii. Weak peroneus longus

iii. Recruited and, therefore, stronger FHL than EHL

Figure 5-22. Dorsal bunion in a teenager. A. Standing lateral radiograph shows dorsiflexion of the 1st ray/MT and plantar flexion of the hallux at the 1st MTP joint. The hindfoot and midfoot are reasonably well-aligned. B. Matching clinical picture. The 1st MT head does not touch the ground in weight-bearing. There is redness, callus formation, and pain over the dorsal aspect of the 1st MT head and under the distal tip of the hallux. C. Standing AP radiograph shows good hindfoot/midfoot alignment, but malalignment at the 1st MTP joint with apparent plantar flexion. D. Matching clinical picture.

3. Imaging

a. Standing AP and lateral of foot

b. Standing AP, lateral, and mortis of ankle

c. Consider CT scan of foot and ankle in all three planes and with 3D reconstruction in older children and adolescents

4. Natural history

a. Persistence of deformity with pain and skin pressure injuries (inflammation, callus formation, blistering, ulceration) on the dorsum of the 1st MT head and/or at the tip of the hallux—in some cases

5. Nonoperative treatment

a. Accommodative shoe wear

6. Operative indications

a. Failure of nonoperative treatment to relieve the pain and skin pressure irritation on the dorsum of the 1st MT head (where it contacts the shoe) and/or at the tip of the hallux (where it contacts the ground)

7. Operative treatment with reference to the surgical techniques section of the book for each individual procedure

a. Combination of procedures (Figure 5-23):

i. Medial cuneiform (plantar flexion) plantar-based closing wedge osteotomy, or medial cuneiform (plantar flexion) dorsal-based opening wedge osteotomy (see Chapter 8)—based on the coexistence of abduction or adduction of the midfoot (see Management Principle #19, Chapter 4)

ii. Transfer anterior tibialis to the 2nd (middle) cuneiform (see Chapter 7)

iii. Reverse Jones transfer of the FHL to the 1st MT neck (see Chapter 7)

iv. Possible plantar capsulotomy of the 1st MTP joint

b. Often, the hindfoot is stiff, but well-aligned. If not, correct the hindfoot deformity with the appropriate osteotomy (see Chapter 8)

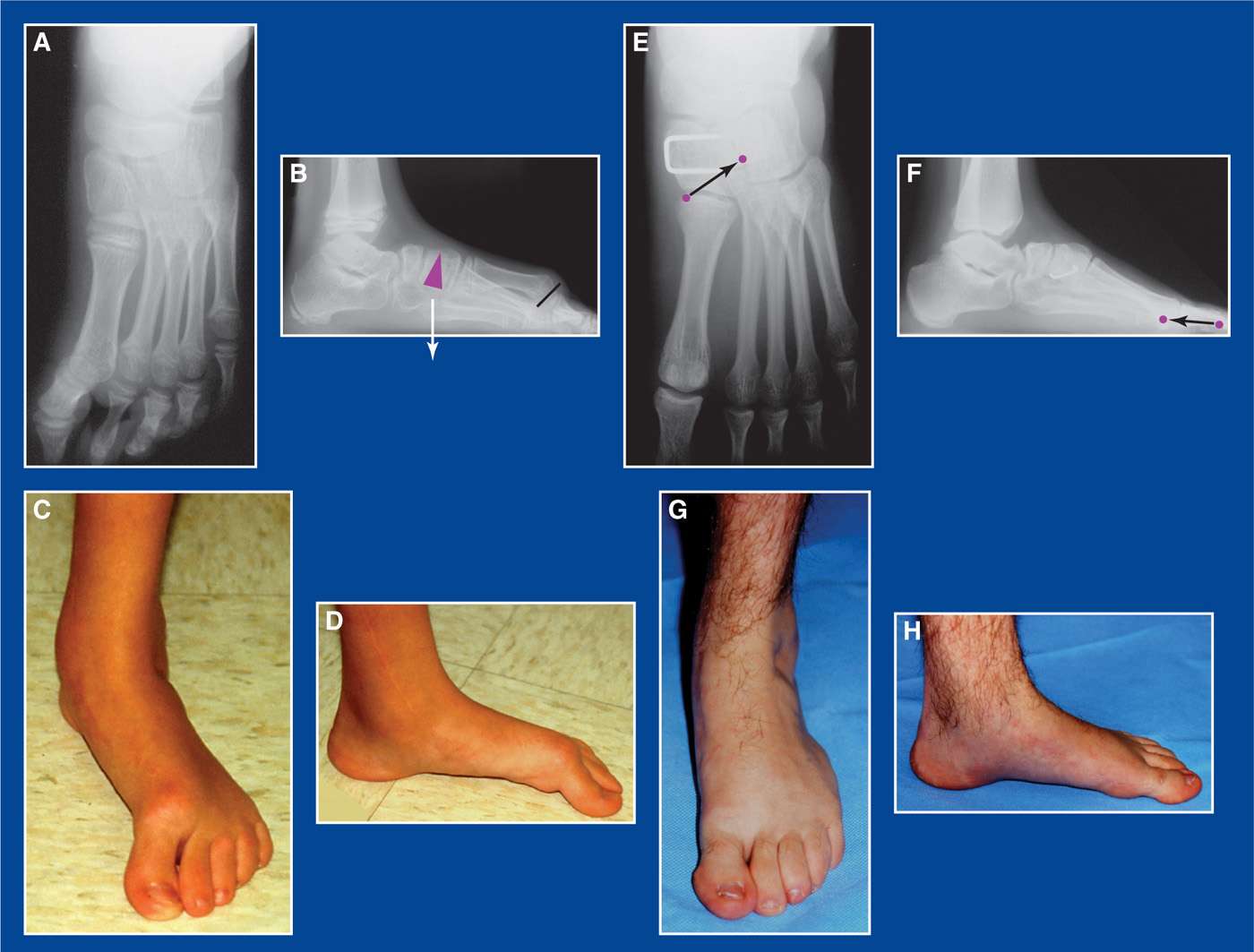

Figure 5-23. A. AP x-ray shows good alignment of the talonavicular joint. B. Lateral x-ray shows good alignment of the subtalar joint, but hyperdorsiflexion of the 1st ray. Purple triangle represents a plantar-based closing wedge osteotomy of the medial cuneiform that was used to correct the forefoot deformity. The black line represents a capsulotomy of the contracted plantar capsule of the 1st MTP joint. C and D. Matching preop clinical photos. E. Post-op AP x-ray shows the internal fixation staple used for the medial cuneiform osteotomy. The purple dots represent the original and transfer locations for the anterior tibialis tendon. F. Ten years post-op lateral x-ray shows the internal fixation staple used for the medial cuneiform osteotomy. The purple dots represent the original and transfer locations for the FHL (reverse Jones transfer). G. and H. Matching clinical photos of the foot 10 years later.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree