29

Flexor Stenosing Tenosynovitis: Trigger Finger and Thumb

Kevin D. Plancher

History and Clinical Presentation

A 45-year-old right hand dominant woman was seen in the office because her right middle finger was stuck in her palm. She reported that her family physician gave her an injection in that finger 6 months ago for her symptoms of clicking and pain over the dorsal aspect of her proximal phalanx of her middle finger. She denies any symptoms of diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, gout, or connective tissue disorders.

Physical Examination

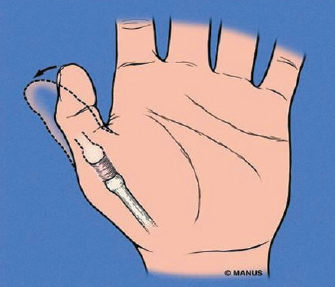

On examination the patient actively initiated extension of her middle finger but stopped with a short arc of motion because of pain. The patient withdrew her hand when passive extension was attempted because of pain. The hand and all digits have no signs of vascular compromise. The patient’s two-point sensory discrimination, as determined by the Weber two-point discrimination test, using a dull pointed eye caliper applied in the longitudinal axis of the digit without blanching the skin, is within normal limits. A tender, palpable nodule is noted over the palmar surface of the second metacarpophalangeal (MP) joint (Fig. 29–1).

Diagnostic Studies

Anteroposterior (AP) and splay lateral radiographs reveal no osteophytes or evidence of osteoarthritis. No soft tissue masses are noted.

PEARLS

- To avoid recurrence of a trigger finger, incise and excise a part of the annular pulley.

- Early treatment and early motion in patients with RA and avoid releasing the A1 pulley.

- Multiple trigger fingers may be a sign of flexor tenosynovitis associated with RA, so avoid releasing the A1 pulley.

PITFALLS

- To avoid nerve injury to the thumb, utilize loupe dissection.

- Avoid releasing the A1 pulley in patients with RA.

Figure 29–1. A palpable mass seen in the thumb pulley.

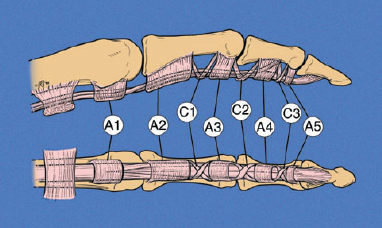

Figure 29–2. The digital flexor sheath contains five discrete “annular bands.”

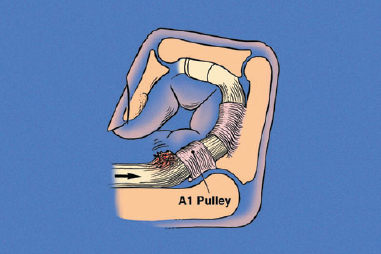

Figure 29–3. The pathophysiology of the trigger finger.

Differential Diagnosis

Tumors

Mass

Infection

Osteoarthritis with osteophytes

Trigger finger

Diagnosis

Flexor Stenosing Tenosynovitis of the Right Middle Finger—“Trigger Finger”

The digital flexor sheath contains five discrete “annular bands” (A1 through A5 pulley) (Fig. 29–2). These pulleys prevent bow-stringing of the flexor tendon and also maximize its efficiency in relation to digital motion. Nutrition of the flexor tendon sheath is dependent on perfusion from the surrounding tenosynovium rather than the vincula system, which perfuses the flexor tendon distally through a small network of vessels. The annular band and the tenosynovium are responsible for the pathophysiology of trigger fingers and thumbs (Fig. 29–3).

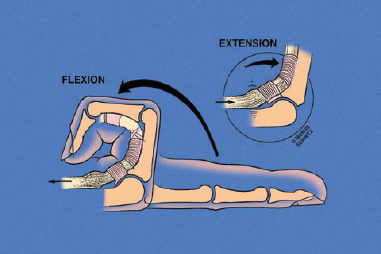

When the normally thin flexor sheath becomes inflamed and thickened, it reduces the space that the tendon has to pass through. The tendon no longer glides freely and the tendon itself may swell up in a balloon-like mass and prevent passage of the tendon through the sheath. Forced movement at this point will drag the enlarged portion (Fig. 29–4) of the tendon through the sheath, producing a snapping sensation and may lead to locking of the finger in flexion. The first annular pulley acts as a fulcrum about which the flexor tendon bends. This fulcrum has been postulated as causing focal tendon degeneration with sheath thickening and tendon nodule development.