First Metatarsophalangeal Joint Arthroplasty

John V. Vanore

William G. Montross

A. Louis Jimenez

Jonnica S. Dozier

First metatarsophalangeal joint (MTPJ) arthroplasty is primarily performed today as a resectional arthroplasty with or without use of a joint implant. Resection arthroplasty without an implant usually involves remodeling of the first metatarsal head with resection of the base the proximal phalanx, that is, the Keller arthroplasty (1,2 and 3). Implant arthroplasty predominantly with the use of silicone-type interpositional devices became very popular in the 1970s (4,5,6,7,8 and 9) but suffered a decline in usage in the 1980s with reports of complications associated with silicone detritus (10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20 and 21). Hinge silicone implants and two-component metallic/polymer joint implants followed (6,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29 and 30). Silicone was still a politically incorrect material mainly due to the breast implant crisis of the 1990s, and two-component total joint systems never really achieved widespread clinical usage (31). As a result, there were surgeons who favored simple resection arthroplasty or arthrodesis versus implant arthroplasty (32,33,34,35 and 36).

Implant arthroplasty may involve relatively simple interpositional devices such as the metallic hemi- or double-stem silicone hinge implants or multicomponent total joint replacement (TJR) systems. In past editions, the history and evolution of implant systems have been discussed extensively. The reader is referred to earlier editions for further information in this regard (37,38 and 39). One relative newcomer to implant arthroplasty is the attempt to address the first metatarsal independently. Hemiarthroplasty of the first metatarsal was initially attempted by Swanson and Joplin among others, but long-term implant instability limited continued use. This has also been somewhat problematic with two-component arthroplasty with loosening leading to implant instability, migration, bone resorption, and pain. In 2005, a metallic cap was introduced to address first MTPJ arthrosis with resurfacing of the first metatarsal head, the Toe HemiCAP (ArthroSurface Inc., Franklin, MA). This concept has been utilized in larger joints such as the shoulder, hip, and knee and subsequently applied to the first metatarsal. Several literature reports show the procedure to be of value in patients with hallux rigidus (40,41 and 42). More recently, several metatarsal implants has been introduced, the MOVEMENT system (Ascension Orthopedics Inc., Austin, TX) and EnCompass (OsteoMed Inc., Dallas, TX) metatarsal resurfacing implant. These implants attempt to address surgical observations that most degenerative changes at the first MTPJ involve the metatarsal head.

INDICATIONS AND CONTRAINDICATIONS

Indications for implant arthroplasty are painful arthritic joints that are deemed to be nonsalvageable with joint preservation techniques (31,34,43). This may be subdivided:

Degenerative arthrosis of first MTPJ

Hallux rigidus

Hallux valgus

Postsurgical arthrosis and/or chronic joint pain

Arthrosis of first MTPJ secondary to arthritides, for example, rheumatoid arthritis

Posttraumatic arthrosis

Patients should be evaluated regarding pathologic indications for implant arthroplasty as well as for alternative surgical procedures including cheilectomy with or without joint preservation-type osteotomy, resection arthroplasty, and first MTPJ arthrodesis. Cartilage replacement or osteochondral autologous transplantation (OATS)-type procedure for repair of excoriated articular surfaces is also an alternative utilizing synthetic, autogenous, or allograft (44). Contraindications to implant arthroplasty would include poor bone stock, poor soft tissue coverage, and joint infection or osteomyelitis. This is of particular importance in the patient with rheumatoid arthritis or gout who may possess poor bone stock that will not retain the implant very well. Patients should be informed that any implant arthroplasty may require revision including removal of the implant.

The general indications for usage of implant arthroplasty (Table 34.1) have changed little over the past three decades, but patient selection has become more stringent. (8,31,37,45) Implant arthroplasty, be it interpositional or a joint replacement procedure, is a joint destructive procedure. As such, surgeons must carefully assess each patient for alternatives (Table 34.2), not only for implant arthroplasty but also for joint preservation whenever possible, particularly in younger, more active patients. It has been suggested that TJR may be appropriate for younger patients requiring a joint destructive procedure (45,46). This is a recommendation not based on studies as the present literature does not document the superiority of any particular procedure over another particularly in the younger patient except for maybe joint fusion.

PREOPERATIVE CONSIDERATIONS

The main indication for implant arthroplasty is hallux rigidus in patients, maybe more so in females, who wish to retain a range of motion (ROM). Generally, first MTPJ fusion is preferable in younger male individuals, where durability is a main consideration. First MTPJ fusion may also be preferred to implant arthroplasty in patients with large degrees of deformity, which may occur in severe or end-stage hallux valgus. At one point, double-stem implant arthroplasty was the preferred technique

in patients undergoing rheumatoid reconstruction or forefoot arthroplasty (47,48 and 49). This has largely been supplanted by first MTPJ fusion due to the stability and long term maintenance of correction that this imparts.

in patients undergoing rheumatoid reconstruction or forefoot arthroplasty (47,48 and 49). This has largely been supplanted by first MTPJ fusion due to the stability and long term maintenance of correction that this imparts.

TABLE 34.1 Indications for Implant Arthroplasty | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Several types of implant arthroplasty may be chosen, including hemimetallic implant arthroplasty, double-stem hinge silicone arthroplasty, or multicomponent TJR. Each of these implants systems will be discussed. Finally, resection arthroplasty will be revisited as an alternative to arthrodesis or implant arthroplasty. Resection arthroplasty is probably best limited to older individuals with a stable hallux interphalangeal joint (IPJ).

RESECTIONAL ARTHROPLASTY

Resectional or excisional arthroplasty has been a traditional surgical treatment for first MTPJ pathology (50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57 and 58). Earlier methods involved first metatarsal head resection with or without excision of the sesamoid apparatus; however, these methods, over time, proved to yield suboptimal results (50,54,59). In 1886, Riedel described the resection of the base of the proximal phalanx and exostectomy of the head of the first metatarsal for the treatment of hallux valgus as an alternative procedure to avoid the deleterious sequelae of first metatarsal head resection (57,60). In 1887, the article “Contraction of the Metatarsophalangeal joint of the Great Toe,” by Davies-Colley (56) followed the same technique employed for the treatment of “hallux flexus.” In 1904, United States Army Captain William L. Keller popularized the surgical technique initially described by Riedel (50,60,61). Keller’s name has since become synonymous with the procedure (57,60).

In Keller’s (3) 1904 article, the surgical technique was employed as treatment for painful bunions and hallux valgus, regardless of the patient’s age or activity. Keller observed the alleviation of pain about the first MTPJ without disrupting the “tripod” structure of the foot during locomotion. Long-term follow-up demonstrated that the Keller procedure created biomechanical impairment of first MTPJ, which resulted in unfavorable outcomes in the younger and/or active population (54,55,59,62,63). As improvements in surgical techniques evolved and the use of rigid internal fixation became a mainstay in foot and ankle surgery, the Keller lost popularity (57,59,64,65,66 and 67). As a result, guidelines have been established to specify which metatarsal osteotomy is appropriate for the patient based on age, activity, bone density, and radiographic findings. The Keller procedure is advocated in elderly patients with increased first intermetatarsal (IM) angles and poor bone stock, limited gait requirements, circulatory compromise, severe first MTPJ degenerative joint disease, infection, or osteomyelitis of the first MTPJ, metabolic diseases such as gout, and reconstruction of the first MTPJ status postsurgical and traumatic intervention (59,63,64). Ideally, the Keller procedure will decrease pain, improve ROM, decrease first IM angle, decrease hallux abductus angle and/or valgus rotation, decrease heloma molle formation between the hallux and second digit, increase the gait pattern, and allow for a greater variety of shoe gear. The ultimate goal is to improve the patient’s lifestyle without subjecting him to an extended and restrictive postoperative course.

TABLE 34.2 Joint Destructive Alternatives | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||

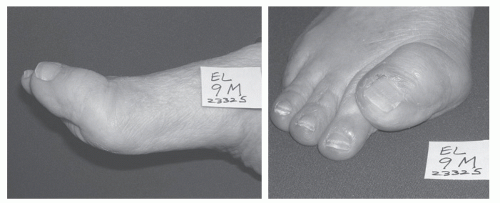

Historically, morbidities associated with the Keller bunionectomy included hallux extensus, degenerative joint disease of the first MTPJ, lesser metatarsalgia, apropulsive gait, dorsal hallux irritation, hallux frontal plane rotation pathologies, a shortened hallux, and cosmetic problems (Fig. 34.1) (54,58,59,61,63,68). The above-mentioned complications are most often a result of too little or too much osseous resection, inadequate muscle-tendon balancing, and/or insufficient soft tissue interposition (54,60,61,69).

Improvements in techniques and indications have led to the metamorphosis of the Keller, which include EHL tendon lengthening when indicated, capsular interposition, Kirschner wire (K-wire) stabilization, decreasing the amount of osseous resection from the proximal phalanx, stabilization of flexor hallucis brevis and/or longus to the base of the proximal phalanx, and angling the osseous resection of the proximal phalanx (57,58,63,65,67,68,70,71 and 72). These improvements have led to more favorable results.

In a retrospective study, conducted by Henry and Waugh (73), Harris-Beath foot printing pads were utilized to assess the

weight-bearing ability of the hallux in 47 feet with a minimum 3-year follow-up. The study reported 18% of the feet demonstrating weight-bearing ability of the hallux when less than two-thirds of the proximal phalanx remained and 74% when approximately two-thirds of the proximal phalanx remained. The authors conclude that toe purchase was proportional to osseous resection of the proximal phalanx. The results from the study clarified Bonney et al’s (59) speculation that one-third to one-half was the optimal amount of bone resection from the proximal phalanx. Henry and Waugh also noted satisfactory results when the preoperative hallux abductus angle was less than 30 degrees, suggesting the Keller procedure would not innocuously correct the deformity without taking a substantial amount of bone (>33%) (73).

weight-bearing ability of the hallux in 47 feet with a minimum 3-year follow-up. The study reported 18% of the feet demonstrating weight-bearing ability of the hallux when less than two-thirds of the proximal phalanx remained and 74% when approximately two-thirds of the proximal phalanx remained. The authors conclude that toe purchase was proportional to osseous resection of the proximal phalanx. The results from the study clarified Bonney et al’s (59) speculation that one-third to one-half was the optimal amount of bone resection from the proximal phalanx. Henry and Waugh also noted satisfactory results when the preoperative hallux abductus angle was less than 30 degrees, suggesting the Keller procedure would not innocuously correct the deformity without taking a substantial amount of bone (>33%) (73).

Figure 34.1 Hallux extensus of the first MTPJ. Patient had discomfort over the IPJ dorsally and the hallux impinged the second digit. |

During late stance and toe-off phase of gait the flexor hallucis brevis and longus stabilize the hallux against the first metatarsal head in preparation for propulsion (74). Should one of these tendons lose their function, stabilization of the hallux and its ability to resist ground reactive forces will be altered (74). When the base of the proximal phalanx is resected, the insertions of the flexor hallucis brevis may be attenuated or sacrificed (60). Failure to preserve or reattach the flexor hallucis brevis may result in hallux malleus or “floating hallux” (74,75 and 76). Mroczek and Miller (77) rectified this potential complication by advocating an oblique resection of the base of the proximal phalanx, which preserves the insertions of the flexor hallucis brevis. The authors noted no occurrence of a “cocked-up” deformity in their patients. The flexor hallucis brevis tendons can also be reattached to the remaining proximal phalanx to achieve the same results as Mroczek and Miller’s modification. In the situation where the flexor hallucis brevis cannot be reattached, due to nonmobile sesamoids or friable residual flexor hallucis brevis tendons, flexor hallucis longus can be utilized to maintain plantarflexion strength (60).

In 1962, Thomas (78) presented a study that compared arthroplasty of the first MTPJ via standard operation versus a modified arthroplasty with distractions of first MTPJ. Thomas noted with joint distraction, via intramedullary K-wire or external staple fixation, that normal tension was restored to the soft tissues, toe length was maintained, and less bone resection was required. This study concluded that patients were pleased and/or satisfied in 96% of the cases and dissatisfied in 4% of the cases, using either technique. Thomas summarizes his study as “the use of a distractor can be expected to produce an improved end result and aid postoperative wound healing.”

Sherman et al (79), in 1984, reviewed 51 Keller procedures in 35 patients with a follow-up of a minimum of 1 year. The average age of the patients was 53 and all were females. They compared two groups: Group A, in which no K-wire was used nor purse stringing of the capsule was performed, and Group B, in which K-wires were inserted for 3 weeks in addition to capsular purse-stringing techniques. Subjective results were slightly better in Group A and the satisfaction rate between the two groups was not significant. They also measured the gap created after each surgical procedure and found that in Group A, the distance was 3 mm and in Group B it was 2.6 mm. Patients in Group B, which had the K-wire retrograded back through the IPJ and into the metatarsal head, were found to have more pain of the IPJ.

In a 2007 retrospective study with an average of 9.1 years, Reize et al (65) evaluated 118 feet with hallux valgus and hallux rigidus following Keller bunionectomies. Improvement in the postoperative ROM was observed when the aftertreatment consisted of K-wire distraction instead of an axial K-wire transfixation. The patients who underwent Keller-Brandes surgery for hallux valgus had less pain when the aftertreatment was carried out using an axial K-wire, while those operated on for hallux rigidus had less pain when the aftertreatment consisted of distraction.

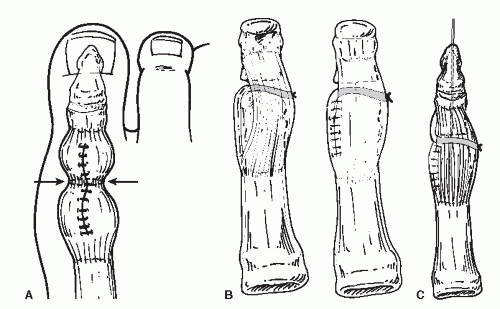

Soft tissue interposition serves as a spacer between the proximal phalanx base and first metatarsal creating a nonpainful fibrous eschar (50,53,55,67,70). There are various forms and techniques for soft tissue interposition of the first MTPJ. These include capsular imbrication, purse-string/hour glass capsulorrhaphy, U, V flaps, etc. (Fig. 34.2) (50,53,67). Others include portions of rolled up tendon called an “anchovy” which can be fabricated from the

posterior tibial tendon, Achilles tendon, extensor hallucis brevis, extensor hallucis longus, etc. (55,71). More current techniques include the use of a dermal allograft to act as a spacer at the proximal phalanx—first metatarsal interface (50,71).

posterior tibial tendon, Achilles tendon, extensor hallucis brevis, extensor hallucis longus, etc. (55,71). More current techniques include the use of a dermal allograft to act as a spacer at the proximal phalanx—first metatarsal interface (50,71).

Figure 34.2 Diagrams demonstrating the hourglass (A), the proximally based U-flap (B), and distally placed U-flaps (C). |

Technically, the U-shaped flap is the more simplistic to create. The surgeon has the option to maintain the base proximally on the metatarsal neck or distally at the metaphyseal-diaphyseal junction of the proximal phalanx. Fashioning a proximal flap is the technique most often employed by the authors since the capsular and periosteal attachments are thicker and less likely to tear on the metatarsal side. Conversely, Roukis et al (80) reported the use of a distally based flap, suggesting this would denervate the first metatarsal, thereby producing an analgesic effect about the first MTPJ. The rationale for this theory is based on a study by Cavalcante et al, which evaluated the innervation of mammalian joints demonstrating that joint capsules and their ligamentous supports are vastly supplied by free nerve endings (80,81). The study suggested that the areas of a joint, subject to the most compression, are the areas that are heavily innervated (80,81).

Kolker et al (71) reported on the use of acellular cadaver dermal matrix (ACDM) as a biologic spacer for soft tissue interposition. ACDM has been utilized in basal joint resection arthroplasty in monkeys to fill bony voids. Histologic evaluation demonstrated revascularization and fibroblastic proliferation filling the void with dense collagenous tissue. The authors hypothesized that using the ACDM as an anchovy and suturing it to the inner side of the capsule could attain similar results. In the presence of an atrophic or iatrogenically compromised capsule and/or periosteum, this alternative soft tissue interposition would be most beneficial.

SURGICAL TECHNIQUE

HEMIMETALLIC IMPLANT ARTHROPLASTY

Implants

Several implants are now available with a variance of features (Fig. 34.3), most are for the proximal phalanx. Today, the implants are generally a cobalt chrome or titanium metallic device with much thinner base dimensions versus their silicone predecessors. It is incumbent upon the surgeon to be thoroughly familiar with the implant system that is being used, including the instrumentation and sequential steps involved with insertion. This following discussion focuses on the Biopro hemi-implant (Biopro, Grand Rapids, MI) and its imitators (Fig. 34.4). They are manufactured of cobalt chromium with a thin, oval base and spade-like stem (31,82). More recently, a hemimetatarsal as well as phalangeal implant with an insertion technique more akin to a two-component arthroplasty has been introduced. The reader is referred to the total joint technique later in the chapter as these implants utilize an intramedullary guide wire with subsequent stepwise instrumentation. One of the unique features of this new implant is that dissection must provide generous exposure to allow for instrumentation as no bone resection is performed prior to reaming of the articular surface and subchondral bone.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree