Femoral Neck Fractures: Open Reduction Internal Fixation

Dean G. Lorich

Lionel E. Lazaro

Sreevathsa Boraiah

INTRODUCTION

Approximately 50% of all hip fractures involve the intracapsular femoral neck (1,2). The total number of hip fractures is projected to increase from approximately 1.5 million in the year 1990 to 6 million by 2050 (3, 4 and 5). The United States has the highest incidence of hip fracture rates worldwide, with an age-adjusted annual incidence of 725 per 100,000 population (4,6). On a per-person basis, hip fractures are the most expensive fracture to treat (7, 8 and 9), with annual estimate hospital cost per hip fracture patient of $25,000 and rising (7,8,10,11).

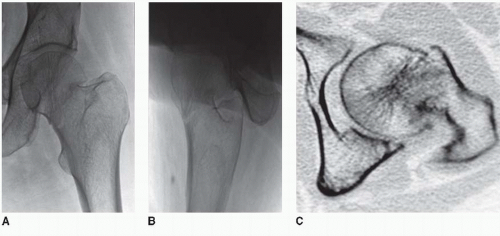

Femoral neck fractures are periarticular injuries where anatomic reduction and normal hip function are often sacrificed to maximize the potential for fracture healing. Traditionally internal fixation has utilized with either a sliding hip screw and side plate or multiple cannulated parallel lag screws (12) (Fig. 15.1). Although there is evidence documenting the superiority of parallel lag screw placement compared with other implants (13, 14, 15 and 16), controversy remains as to the optimal treatment of choice (17). Implants that allow sliding permit dynamic compression at the fracture site during axial loading, but some shortening of the femoral neck invariably follows. Until recently, a healed femoral neck fracture without implant failure or the development of avascular necrosis (AVN) was considered a success (Fig 15.1). Healing, however, comes at the expense of a shortened femoral neck. This impacts the biomechanics of the hip joint, which is either accepted or overlooked. The negative impact of altered hip mechanics following fracture has been studied and reported. Femoral neck shortening was shown to be associated with significantly lower physical function on SF-36 subscores (18). It has also been shown to correlate with decreased quality of life (19).

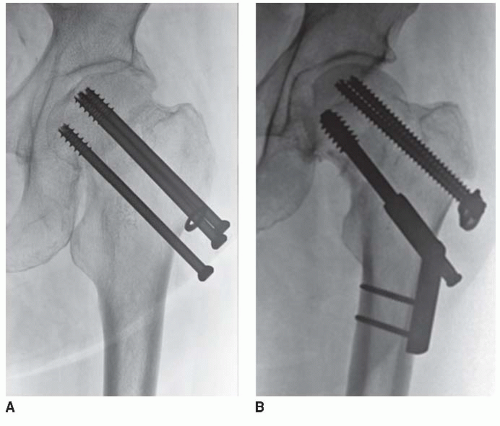

This leads us to believe that anatomic reduction and internal fixation, which is maintained through fracture healing, is critical for successful outcomes. With an increased emphasis on preservation of hip function, understanding the pathomechanics and preservation of hip anatomy is imperative to restore in order to maximize the chance of a successful outcome. Anatomic reduction with intraoperative compression using length-stable devices to maintain the reduction can lead to high union rates with minimal shortening and better functional outcome.

This leads us to believe that anatomic reduction and internal fixation, which is maintained through fracture healing, is critical for successful outcomes. With an increased emphasis on preservation of hip function, understanding the pathomechanics and preservation of hip anatomy is imperative to restore in order to maximize the chance of a successful outcome. Anatomic reduction with intraoperative compression using length-stable devices to maintain the reduction can lead to high union rates with minimal shortening and better functional outcome.

FIGURE 15.1 AP radiographic view demonstrating two sliding constructs that healed in a shortened fashion. |

There is a large body of literature that documents high complication and reoperation rates following internal fixation of intracapsular femoral neck fractures (20). This may be related to both mechanical and biological problems related to femoral neck fracture healing. The femoral neck is intracapsular, is bathed in synovial fluid, and lacks a periosteal cambium layer that is necessary for callus formation. From a structural standpoint, the bone screw interface is strongest immediately after surgery and weakens over time. Restoring anatomic fracture reduction often requires direct visualization prior to fixation. The most widely used classification for femoral neck fractures is the Garden classification. However, this classification scheme is based on the anteroposterior (AP) radiographs alone and does not consider the lateral or sagittal plane alignment. Recent studies have shown posterior roll off or angulation of the femoral head leads to increased reoperation rates (21, 22 and 23) (Fig. 15.2).

The authors report a 56% reoperation rate if the posterior tilt is >20 degrees (21). If anatomic reduction is the goal, it is important to address malalignment in all planes. We believe that the best and most consistent approach to achieve an anatomic reduction of this difficult fracture is through open reduction, direct visualization, and fixation of the fractures.

The authors report a 56% reoperation rate if the posterior tilt is >20 degrees (21). If anatomic reduction is the goal, it is important to address malalignment in all planes. We believe that the best and most consistent approach to achieve an anatomic reduction of this difficult fracture is through open reduction, direct visualization, and fixation of the fractures.

INDICATIONS AND CONTRAINDICATIONS

The indications for open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) of femoral neck fractures continue to expand. It is important to distinguish between low-energy fragility fractures in elderly patients and younger patients with high-energy femoral neck fractures since the approach to treatment and methods of fixation vary. For geriatric patients with mechanical ground level falls, a complete assessment of the patients’ status is helpful in selecting surgical options. In this group of patients, our treatment algorithm is as follows: (a) ORIF is indicated for most patients <65 years of age, regardless of fracture pattern, (b) patients aged 65 to 85 years receive ORIF for Garden I and II fractures, and selected physiologically younger patients are also treated with ORIF for displaced fractures (Garden III and IV), and (c) patients >85 years with a Garden I or II fractures should also be considered for ORIF. Garden III and IV fractures in this age group are treated with arthroplasty.

When assessing the physiological age of a patient, one should consider multiple factors including, but not limited to, chronological age, preinjury activity level, preinjury ambulatory status, and potential patient compliance. Regardless of the fracture pattern, in patients presenting with significant medical comorbidities, advanced physiologic age, degenerative changes of the femoral head, or pathological fractures, hip arthroplasty should be considered. There is a large body of literature that supports the use of hemiarthroplasty or total hip arthroplasty in these situations (24). These are only guidelines for treatment, and the surgical treatment must be individualized to every patient.

For nondisplaced and Garden I femoral neck fractures, we usually perform in situ fixation using a percutaneous approach to relieve pain, permit mobilization, and decrease the small chance of further fracture displacement. There are several randomized controlled trials comparing closed reduction and screw fixation with arthroplasty for displaced femoral neck fractures in the elderly. These studies report fewer complications and better outcomes with arthroplasty. However, there are no studies that we are aware that compare open reduction and length-stable internal fixation to arthroplasty for comparable fractures.

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

History and Physical Examination

A thorough history and physical examination is essential. In geriatric hip fracture patients, a complete medical assessment and risk stratification should be performed with the assistance of an internal medicine specialist. On physical exam, the affected leg is usually externally rotated and shortened. Movement of the limb is painful, and range of hip and knee motion is resisted by the patient secondary to pain. A thorough neurovascular examination and assessment of the soft tissue and the skin should be made. Cutaneous bruises indicate that the patient may be anticoagulated. Traction has not shown to be of any benefit. A knee immobilizer may be helpful to immobilize and relieve pain.

In younger patients (<50 years) with a displaced femoral neck fracture, urgent reduction and fixation of the femoral neck is indicated. Ipsilateral femoral neck fractures are seen in 3% to 5% of patients with high-energy femoral shaft fractures.

IMAGING STUDIES

A radiographic series for a patient with a suspected hip fracture should consist of an AP and cross-table lateral radiographs of the affected hip, an AP pelvis x-ray and full-length femur films of the ipsilateral side. We prefer a cross-table or Clayton-Johnson lateral, because a frog lateral position is difficult to obtain secondary to pain. If any uncertainty exists as to the fracture pattern, a traction internal rotation view can be very helpful. As stated earlier, the Garden classification of femoral neck fractures is based solely on the AP view of the hip. Valgusimpacted fractures, which are typically amenable to in situ percutaneous pinning, may have posterior roll off of the femoral head. Unfortunately, the Garden classification does not take into account posterior displacement or angulation of the femoral head best seen on the lateral x-ray. When anatomic reduction of the fracture is planned, a three-dimensional assessment of the fracture should be obtained.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree