Chapter 24 Facet Subluxation Syndrome

After reading this chapter you should be able to answer the following questions:

| Question 1 | What is the primary function of the lumbar facet articulation? |

| Question 2 | What is the pattern of referred pain from spinal facet joints? |

| Question 3 | What are the 10 specific proposed effects that manipulation may have on spinal facet articulations? |

Vertebral zygapophyseal (facet) joints have long been recognized as a source of spinal pain and dysfunction.1–11 In 1933, Ghormley12 introduced the term facet syndrome, but after the work of Mixter and Barr in 1934,13 interest in intervertebral discs and irritated nerve roots overshadowed facet joints as a source of low back pain. In more recent years, the facet articulations have received much more attention. Kirkaldy-Willis and Burton14 consider lumbar facet syndrome a “commonly occurring condition,” and Cox4 considers “facet subluxation syndromes probably the most common condition encountered in low back pain patients.”

This chapter explores the role of facet joints in spinal pain and pathomechanics.

Facet Syndrome Defined

Facet syndrome may be broadly defined as pain or dysfunction arising primarily from the zygapophyseal joints and their immediately adjacent soft tissues. Earlier definitions include the following10:

1. The condition characterized by an overriding of the facets of adjacent vertebrae whereby the intervertebral foramina are narrowed from the superior to the inferior

2. A state of subluxation with tension, pressure, stretching, or irritation of the vertebral joint capsule as a result of postural strain or trauma but without narrowing of the related foramina

Specific diagnostic criteria for facet syndrome are discussed later in this chapter.

Facet Clinical Anatomy and Function

The lumbar spine has been the focus of most study relating to facet joint mechanics. A primary function of lumbar facet articulations is resistance to rotational and shear forces, thereby protecting the disc.1,15 Lumbar facets also have a role in weight bearing. Normally they carry approximately one sixth of the total axial load of the vertebral motion segment.1 Because of their relatively small surface area, this is roughly equivalent to 10 times the weight per square inch borne by the standing knee joint.4 Axial weight bearing is increased during extension and reaches up to 70% of the intervertebral compressive force in cases of degenerative disc narrowing.1 Increased zygapophyseal weight bearing is often considered an important component of lumbar facet syndrome that can readily be measured radiographically.4,10,16,17

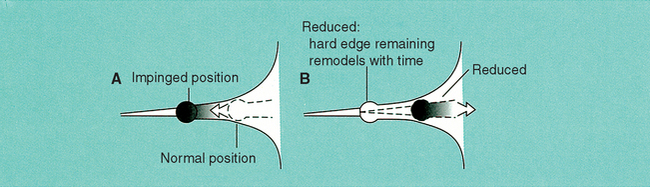

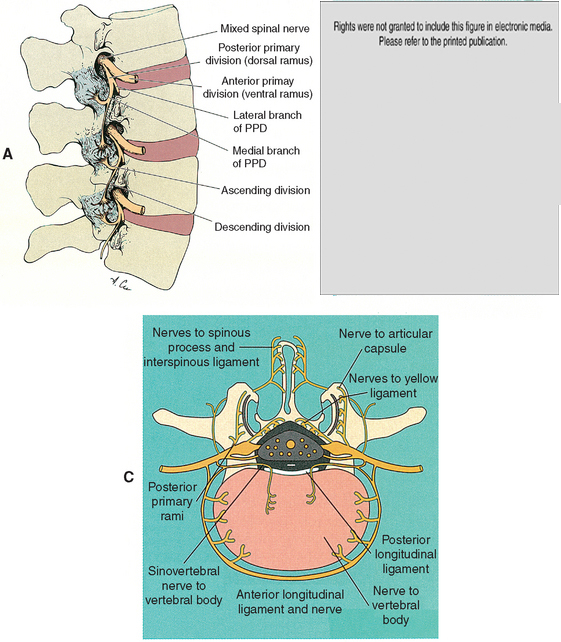

The innervation of the facet joints is well known. (See Chapter 3.) The joint capsule and adjacent tissues are innervated by twigs from the medial branch of the posterior primary rami, each facet receiving innervation from two spinal levels.5,8–10,18,19 As the medial branch of the posterior primary ramus traverses inferior to the facet surfaces, it travels through a bony tunnel covered by the mammilloaccessory ligament.8,9,19 Direct nerve entrapment is possible at this site as a result of overriding (imbrication) of facets that may occur with disc thinning or facet degeneration (Figure 24-1).19

(Figure 24-1, A, modified from Cramer D. Basic and clinical anatomy of the spine, spinal cord and ANS. St. Louis: Mosby; 1995. Figure 24-1, B, modified from Giles LGF. Anatomical basis of low back pain. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1989.)

Meniscoids

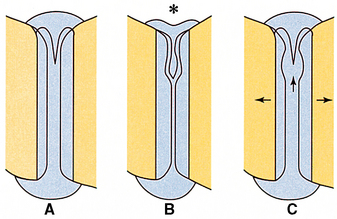

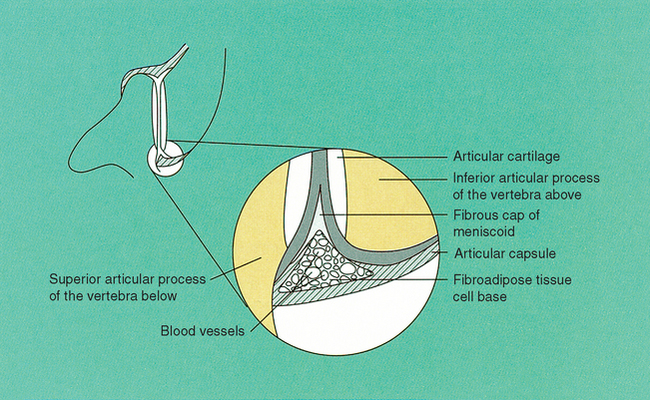

Intraarticular joint inclusions (synovial folds) have been described in all spinal zygapophyseal joints,11,20 but most of the interest has centered on the lumbar spine. Typically, these structures consist of three parts: (1) a fibroadipose or loose connective tissue base arising from the joint capsule, (2) a highly vascularized synovial inclusion zone, and (3) a tip of dense connective tissue or cartilaginous tissue that projects between the articular surfaces7,14,18,20–23 (Figure 24-2).

Figure 24-2 Diagrammatic representation of the fibroadipose meniscoid of a facet joint according to Engel and Bogduk.

(Modified from Bergmann T, Peterson D, Lawrence D. Chiropractic technique. Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone; 1993.)

The primary functions of meniscoids are as follows18,20,21:

1. To fill space at the periphery of the joint surface

2. To increase surface area contact and therefore transfer load

3. To cover exposed articular surfaces and protect joint margins during flexion and extension

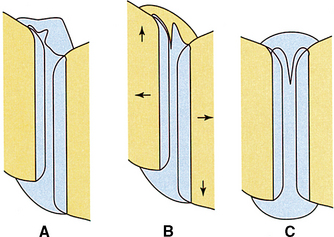

Mechanically, meniscoids have been implicated as a cause of the acute “locked back” or torticollis by becoming entrapped between the articular surfaces.* The success of spinal manipulative therapy directed at the facet joints may be explained by this mechanism. Distraction of the articular surfaces may release the entrapped meniscoid and allow resolution of the consequent muscle spasm (Figures 24-3 to 24-5).* Other proposed mechanisms of meniscoid-related facet joint dysfunction include the following:

1. Entrapment of the meniscoid outside the joint surfaces in the capsular recess (see Figure 24-2)18,27

2. A free fragment of facet cartilage avulsed from the articular surface but still attached to the capsule18

3. Deformation of hyaline cartilage by presence of the meniscoid

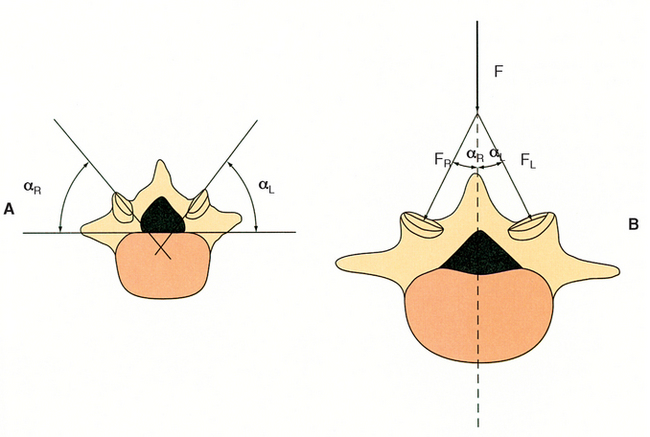

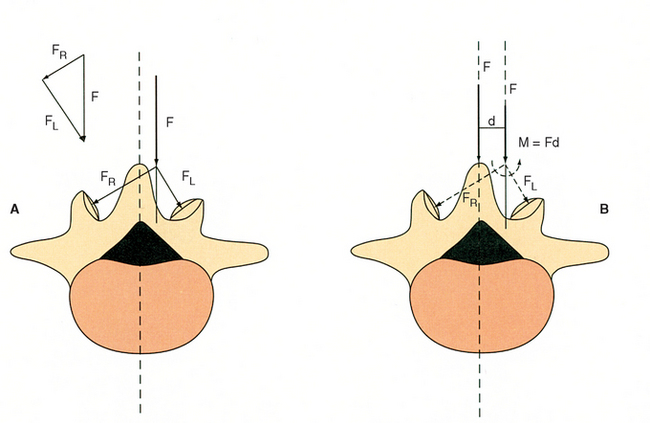

Tropism

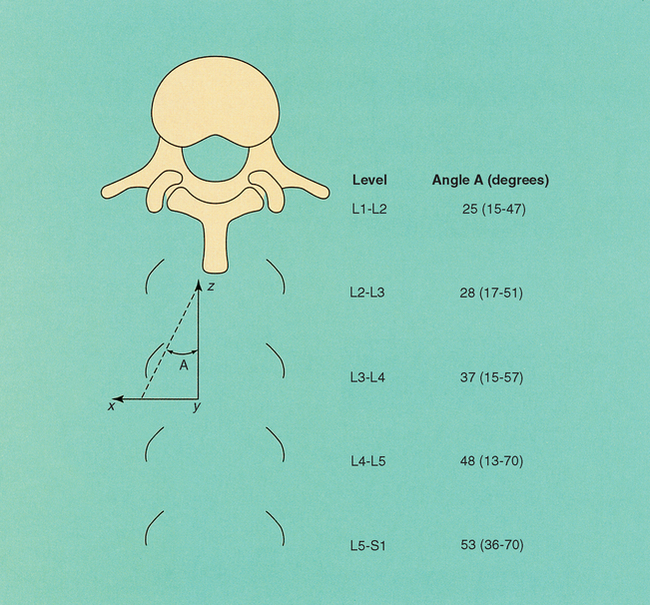

Normally, the upper lumbar facets are essentially sagittal in orientation and the lower lumbar joints are more coronal (Figure 24-6).15,28 Tropism refers to an anomalous condition in which the articular facings are asymmetric.4 Because the facets guide the motions of the lumbar spine,1 it appears logical that asymmetric joint angles could disrupt normal biomechanics. Cyron and Hutton15 have demonstrated unequal articular forces produced in tropism with consequent increase in pressure and arthrosis at the more oblique, that is, more sagittal facet (Figures 24-7 and 24-8). This results from rotational torsion occurring at the joint. Increased wear on the anulus of the disc is postulated to occur as a result of these same forces.15 Cox4 states that “patients with anomalous facet facings are at high risk for developing a disc lesion on rotation.” Noren et al.29 demonstrated that tropism was associated with an increased risk of disc degeneration. Other studies, however, have failed to find association between tropism and disc degeneration,30 disc herniation,31 and symptom reproduction by discography.30

Facet versus Disc Degenerative Joint Disease

Degenerative joint disease (DJD) may occur at different rates in the discs and facets of the same motion segment. Ziv et al.32 found severe fibrillation in histologic specimens of facets after the age of 30 years. Degeneration was more pronounced in the superior than in the inferior articular process. It was noted that even “young adults” showed ulceration or severe fibrillation, and that facet degeneration preceded disc degeneration. It was concluded that these facet changes were a likely source of back pain.

Beaman et al.33 also demonstrated that facet DJD occurs with or without disc DJD. These findings support the presence of a clinical entity unique to the facet joints, which can occur independent of concurrent discal pathology or pathomechanics. They also counter previous studies that concluded that facet degeneration occurs only as a result of disc DJD.34 It should be noted that disc and facet degeneration do often occur together, and either or both may be a primary pain source.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree