Less common extrinsic disorders that may cause a painful “hip” after THA include vascular claudication, especially due to disease of the internal iliac artery or Leriche syndrome with buttock claudication. Neuropathic pain should be considered in patients with diabetes mellitus (diabetic lumbar plexopathy) or a previous injury leading to sciatic or femoral causalgia. Vascular and neurologic consultation will be appropriate if these diagnoses are suspected. Rarer causes of referred pain in the hip from extrinsic disorders include hernias,7 retroperitoneal abscess or tumor, metabolic bone disease, and metastatic cancer.8

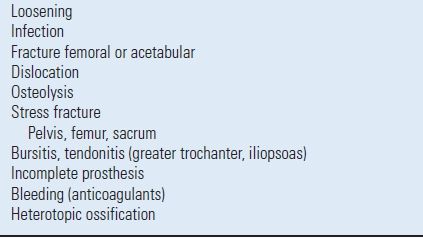

The most common intrinsic cause of a painful THA is aseptic mechanical loosening. However, the list of other intrinsic causes of a painful THA is extensive (Table 5.2). These include acute and chronic infection, periprosthetic fracture of the femur or acetabulum, occult fracture of the femoral component,9 stress fracture of the femur10 or acetabulum, bursitis-tendonitis (greater trochanter or iliopsoas),11 and an incomplete prosthesis (hemiarthroplasty with acetabular pain). Dislocation and subluxation of the THA may be a dramatic or subtle cause of pain. Bleeding into the hip associated with anticoagulants has been reported as a cause of pain after THA.12 Heterotopic ossification is not commonly a cause of pain, although the more extensive grades can limit a patient’s motion and function. However, in the early stage of maturation or if there is a fixed deformity associated with the heterotopic bone, patients may report moderate or severe pain.

TABLE 5.2 Intrinsic Causes

The late phenomenon of periprosthetic osteolysis has commonly been considered to be asymptomatic and not a cause of a painful THA unless there is a periprosthetic fracture or component loosening.13 However, the author has treated many patients with hip pain in association with osteolysis, in whom pain was presumed due to synovitis or fluid pressure in the prosthetic hip joint. These patients require careful evaluation prior to operative treatment.

HISTORY

A careful history is the most important aspect of evaluation of a patient with a painful or problematic THA or pain in the extremity after THA. The location, severity, temporal onset, precipitating causes, and character of the pain may provide important information to direct a more detailed physical examination and radiographic evaluation.

The temporal onset of the pain may be the most crucial aspect of the history. Persistent moderate or severe pain after THA, without a pain-free interval, is suggestive of infection, inadequate initial implant fixation, fracture, or an incorrect initial diagnosis. As mentioned previously, arthritis of the hip and lumbar radiculopathy or spinal stenosis often occur in the same patient population, making the presence of both disorders common. Historical comparison of location and radiation of pain may provide useful information. The onset of pain many years after a pain-free, well-functioning THA usually suggests mechanical loosening, but the differential diagnosis remains extensive, with chronic low-grade infection and bearing surface wear and osteolysis to be considered.

The location of pain in the groin or anterior proximal thigh is usually associated with an intrinsic THA problem, such as acetabular loosening, synovitis or bleeding, or iliopsoas tendonitis-bursitis. Posterior buttock pain, with or without posterior thigh pain, usually suggests a problem of the lower lumbar spine, especially if associated with radiation of the pain below the knee or any symptoms in the foot. Specific localization of pain in the anterior mid or distal thigh has been associated with femoral loosening or modulus mismatch with an uncemented femoral component.

The severity of pain is an important consideration. Slight occasional pain that does not affect function may be observed. Moderate or severe pain in the THA or lower extremity that requires medication usually suggests that this is a serious problem that requires evaluation. Pain that increases with ambulation and is relieved by rest is usually associated with mechanical loosening. So called start-up pain, produced with getting up from a chair or bed and starting to walk, has been associated with acetabular component loosening and micromotion or loosening of uncemented femoral components. Night pain, rest pain, or constant pain is worrisome for deep infection, causalgia, or tumor.

The precipitating cause of the pain may be also helpful in the diagnosis of a painful THA. The onset after trauma, such as a fall or motor vehicle accident may suggest a fracture, loosening, or dislocation-subluxation. Pain occurring after a systemic illness or extensive dental, gastrointestinal, or urological procedures may be indicative of hematogenous infection of the hip. Pain associated with the onset of new anticoagulant or antiplatelet medication should suggest bleeding or hematoma in the THA.

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

A careful and complete physical examination of the patient with painful or problematic hip arthroplasty should include the lumbar spine, knee, hip, and a brief neurological assessment. The patient’s gait should be observed, if possible, without a walking support, to determine the type and severity of limp. An antalgic limp may be seen with either a hip problem or lumbar stenosis, but a Trendelenburg gait or abductor lurch is more suggestive of an extrinsic hip problem. The measurement of true and apparent leg lengths with a tape measure or wooden blocks is helpful when there is an associated complaint of leg length inequality. An apparent leg length discrepancy may indicate an abduction or adduction contracture of the hip, pelvic obliquity, or lumbar scoliosis due to degenerative disc disease. Progressive shortening of the leg usually indicates femoral component subsidence and/or acetabular component migration.

The skin of the hip, thigh, and buttock should be inspected and palpated, to look for scars, sinus tracts, and tender bursae, masses, or hernias. Examination of the range of motion and muscle testing of the involved hip should be performed in both the supine and lateral decubitus positions. Pain throughout passive range of motion suggests infection, fracture, or gross loosening of a component. Pain with active motion or at the extremes of rotation is suggestive of component loosening. Pain with resisted ipsilateral straight leg raise suggests hip pathology. Pain with ipsilateral or contralateral passive straight leg raise suggests a radiculopathy or lumbar disc problem. Pain that is exacerbated by resisted seated hip flexion usually suggests that the problem is coming from the hip, rather than the lumbar spine, and may be present with iliopsoas impingement or tendonitis. Finally, a brief neurological examination of both lower extremities should be performed to exclude a lumbar spine problem or an unusual neuropathy. An abnormality of the peripheral pulses may suggest vascular claudication as a source of pain.

RADIOGRAPHIC AND LABORATORY EVALUATION

Rather than following a strict algorithm,4,14,15 the author suggests that all patients with a painful or problematic hip after arthroplasty be evaluated with a minimum of plain radiographs of the hip and a serum C-reactive protein (CRP) (or erythrocyte sedimentation rate [ESR]). Thereafter, the sequence of evaluation can proceed from the coordinated synthesis of history, physical examination, and these two initial tests.

Plain Radiographs The minimum plain radiographic evaluation of a painful or problematic hip arthroplasty should include: anteroposterior (AP) pelvis centered over the pubis, AP and frog-lateral views of the entire femoral component, and a “cross-table” lateral or oblique view of the acetabular component. Efforts should be made to obtain the early postoperative radiographs and other sequential radiographs for a comparative review. If there is uncertainty about the model of components evaluated, the implant “stickers” should be requested from the hospital where the index arthroplasty was performed.

The Harris criteria for loosening of a cemented femoral component have been widely used both clinically and in outcome studies. Possible loosening is defined as a new radiolucent line involving 50% to 99% of the bone-cement interface. Probable loosening is considered if there is a continuous bone-cement radiolucent line, without component shift or migration. A femoral component is definitely loose if there is component migration (≥3 mm), cement or component fracture, or a new stem-cement radiolucent line (so-called debonding). However, it has been suggested that a stem-cement radiolucent line may not indicate definite loosening of femoral components with a polished surface finish.

Radiographic evaluation of cemented acetabular components is somewhat more controversial. However, most agree that a complete radiolucent line (of any width) at the bone-cement interface, cement fracture or component shift or migration (≥3 mm) indicates definite component loosening.16

The radiographic evaluation of cementless (porous-coated or hydroxyapatite coated) femoral components must take into account the specific type of component. Engh has described the radiographic signs that are predictive of the fixation status of extensively or fully porous-coated femoral components.17

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree