Chapter 12 Establishing Rapport

Personal appearance is a significant part of nonverbal communication. Patients consider house staff who wear white coats with conventional street clothes as more competent than those who wear scrub suits. If white coats are worn, the patient sees only the collar, tie, and shoes, and it is therefore important to keep these items neat.

Patient Satisfaction

Although patient satisfaction is strongly associated with the length of the visit, it can be further enhanced by spending some time talking about nonmedical topics. Even brief chatting about the weather or something nonmedical can give the impression that more time was taken with the patient, thereby reducing the feeling of being rushed through the visit (Gross et al., 1998).

Communication

Verbal Communication

Hand-on-the-Doorknob Syndrome

Physicians in private practice who have established rapport during an ongoing relationship with patients communicate more easily than do physicians seeing a patient for the first time in an emergency department (ED). Korsch and Negrete (1972) showed that ED physicians did more talking than the patients, although their perception was just the opposite. This was attributed to interaction with unfamiliar patients by house staff in a setting where the stress level is high and the orientation therapeutic. However, Arntson and Philipsborn (1982) found that physicians in private practice for 26 years who knew their patients and saw them in a low-stress situation for diagnosis or health maintenance also talked more than the patients (twice as long). One difference in the two settings was a strong, reciprocal affective relationship between physician and patient in the private office. If either made an affective statement, the other would respond similarly, whereas in the ED, patients expressed twice as many affective statements as did the physicians.

Paralanguage

In a study of recordings of surgeons who had been sued and those who had not, the sued group could be identified by their tone of voice. They sounded dominant, whereas the nonsued group sounded less dominant and more concerned. “In the end it comes down to a matter of respect, and the simplest way that respect is communicated is through tone of voice” (Gladwell, 2005, p.43).

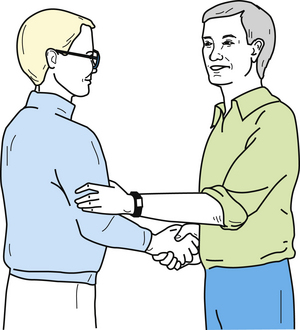

Touch

A close personal interest in the patient can be communicated by the appropriate use of touch. The most socially acceptable method in this country is a handshake, enabling the physician to establish early contact with the patient. The handshake, properly used, can convey to the patient sincerity and interest as well as security and poise. It is an inoffensive intrusion into the other person’s area of privacy and can be extended under certain circumstances to include the application of the left hand to the lower or upper arm. This technique is often used by politicians to emphasize sincerity and concern (Figure 12-1). A variation of the politician’s handshake is the “double-hander,” which some equate to a miniature hug.

Body Language

The astute physician will cultivate observational skills that enable the detection of hidden or subtle clues to diagnosis contained in the patient’s nonverbal behavior. Kinesics is the study of nonverbal gestures, or body movements, and their meaning as a form of communication. However, specific gestures and their interpretation are of importance only when judged in the context of the circumstances surrounding them. Body language alone does not reveal the entire behavioral image any more than verbal language does alone. Just as one word does not make a sentence or even have much meaning without the sentence, a single gesture has clinical relevance only as part of a sequence of actions. Although they have significance, individual signs are not reliable when they stand alone; they are meaningful only when considered in the context of a person’s total behavioral pattern.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree