Fig. 3.1

Increasing rate of positional plagiocephaly (black) in comparison to craniosynostosis (gray) following AAP recommendations for SIDS prevention (1992)

Several tertiary care centers with craniofacial specialists published data showing cases of PPP increasing exponentially after 1992 [3, 4]. One study demonstrated a fivefold increase in posterior plagiocephaly comparing 1990–1992 with 1992–1994, and all infants, retrospectively, were found to be supine sleepers [3]. Because the data emanate from academic medical centers, the true incidence and prevalence of PPP in America could be even larger than reported. These populations could reflect only cases geographically near the tertiary care centers or severe enough to be referred. In the United States, the healthcare system is not conducive for an evaluation of PPP of a large number of children presenting for routine visits. In the Netherlands, on the other hand, the Infant Health Care Program provides for the evaluation and counseling for well-child visits. In September 1995, the prevalence of PPP presenting in 7,609 children for well-child examinations was noted to be 9.9 % in infants less than 6 months of age [5].

Epidemiological findings concerning the increase in PPP in the current literature seems to parallel the application of the recommendations for supine sleeping position established by the AAP for preventing SIDS [6]. Currently, the prevalence of PPP ranges from 18 to 19.7 % in healthy infants and varies with age [7].

3.1.1 Incidence

The incidence of PPP varies from less than 1/300 of live births [8] to more than 48 % healthy children aged less than 1 year [3], depending on the sensitivity of the criteria used for diagnosis [9]. On the other hand, the incidence of isolated lambdoid craniosynostosis (synostotic plagiocephaly) is quite rare and is estimated to be around 3 in 100,000 births, equal to 0.003 % [10].

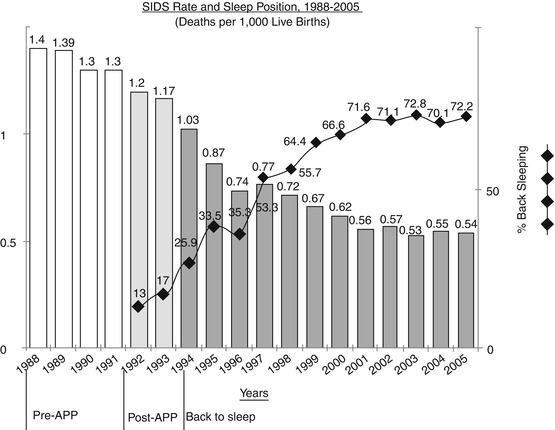

Before 1992, when more than 70 % of the children were placed to sleep in the prone position, the frontal PP was present in 1/300 live births [9]. Since 1992, there has been a significant increase in the diagnosis of PPP, an increase of more than sixfold between 1992 and 1993. Increasing incidence of PPP is probably related to the recommendations given by the AAP and other scientific societies about the opportunity to let the infants sleep on their backs. Sleeping in the prone position or, to a much lesser extent, on the side (as the newborn tends to “fall” in the prone position) during early childhood is, in fact, demonstrated to be correlated with SIDS. After that, in 1992, the campaign “Back to Sleep” was launched, the habit of letting the infants sleep in the prone position greatly diminished, and the incidence of SIDS decreased accordingly by more than 40 % [2] (Fig. 3.2).

Fig. 3.2

The habit to put newborns to sleep in supine position, recommended by AAP in 1992, led to a dramatic decrease of SIDS rate from 1.4 in 1988 to 0.5 in 2005

A close correlation of the increased prevalence of stiff neck postural torticollis (PT) and PPP with recommendations for the prevention of SIDS was demonstrated, suggesting the existence of a causal link [3, 4, 10, 11].

Since the AAP’s Back to Sleep campaign, the incidence of SIDS has decreased more than 40 % [9]. Prior to 1992, the incidence of PPP was estimated at 1 in 300 infants [12]. After the recommendation, a dramatic increase of up to 600 % in referrals for plagiocephaly was reported by primary care providers and craniofacial centers [13]. Because many positional head shape deformities improve with time [14], the existence of PPP is higher in younger infants, and estimates of prevalence are highly age dependent.

The diagnosis of PPP in at least three craniofacial centers has increased substantially during the 1990s. There is a strong temporal association between the onset of this increase and the AAP recommendation to avoid the prone sleeping position for most American neonates. PPP should be a preventable condition. Awareness of PPP should prompt coupling of education of new parents and other infant caregivers about SIDS and sleep position with education about the importance of alternating head position while the infant is supine or side lying1. If these assumptions are correct, education of parents regarding the importance of head rotation should result in a prompt reduction in PPP [3].

A cross-sectional study performed in healthy newborns showed that the incidence of localized cranial flattening in singletons was 13 %; other anomalous head shapes were found in 11 % of single-born neonates. In twins, localized flat areas were much more frequent with an incidence of 56 % [20].

The incidence of PPP varies widely and is based on anecdotal evidence of increase in the number of referrals to specialty clinics. Five studies have produced varying results, indicating that the incidence of PPP ranges from 3.1 to 61.0 %.

A recent cohort study estimated the incidence of PPP using four community-based data collection sites in infants ranging from 7 to 12 weeks of age. The estimated incidence of PPP was found to be 46.6 %. Of all infants with plagiocephaly, 63.2 % were affected on the right side and 78.3 % had a mild form [21].

Other associations with PPP have been widely acknowledged, such as gender (male/female ratio = 1.5:1–3:1) [5, 16, 17], limited head rotation, torticollis, multiple births, birth parity, duration of labor, mode of delivery, iatrogenic cephalohematoma, uterine anomalies, minor auricular deformations, method and position of feeding, preferential head positioning, and ratio/duration of prone versus supine lying [9, 15–17, 22–24]. A cross-sectional study [25] undertook a structured visual examination of 346 infants under 10 months of age, classifying cases into six severity categories. The paper addresses the problem of definition for the disorder. They observed some degree of occipital flattening in 15.2 % of subjects; however, when limiting the inclusion criteria to occipital flattening with associated skull base and facial asymmetry, the incidence decreased to 1.5 %. No discussion of power calculations was given, bringing the issue of external validity into question, given the relatively small sample size for a population-based study. A large prospective Dutch study [5] (n = 7,609, age <6 months) also noted occipital flattening and asymmetric position of the ears in 7.5 and 1.2 % of cases, respectively, thus providing close agreement with the cross-sectional study [25]. However, 167 examiners were involved in the study and, by virtue of its subjective methodological design, necessarily introduced considerable experimental bias2.

3.1.2 Prevalence

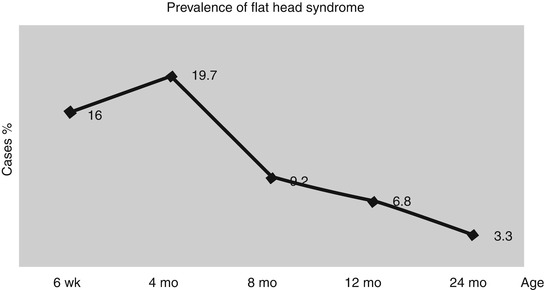

The prevalence of PPP is equal to 13 % in healthy newborns and rises to 16 % at 6 weeks [18] and to 19.7 % at 4 months of age [20] and decreases to 3.3 % at 2 years [26]. The prevalence is higher in the first 7 weeks after birth. The presence of PPP at birth is a predictive factor for the occurrence of the form at 7 weeks [17]. Unilateral PPP interests with greater frequency the right side of the head (54–71 %), possibly because the occipital anterior presentation of the fetus at birth is most common, but it is believed that it can also be due to innate brain factors, similar to those that determine the prevalence of most right-handed individuals [20]. Other authors believe, however, that the position of the fetus in utero seems to be the most responsible for the predominance of the occipital right form: 85 % of infants with vertex presentation assume, in fact, the position of the occipital left front [27, 28].

The prevalence of TP in infants under 6 months of age increased from 8.2 % in 1997 [5] to 12.2 % in 2004 [29]. Despite the increase in the PPP, there is no doubt that the recommendation to let infants sleep on their backs was followed in the vast majority of cases. At the same time, the widespread use of child safety seats for car transport or while walking, besides laws and rules on car transport of kids, has encouraged the spread of these devices. In the early 1990s, these products were reviewed and made more ergonomic and more convenient and practical for parents. Multifunctional seats, for example, which have become extremely popular in a mobile society like the present one, can be used to carry children in cars, as a stroller, high chair, and so on. In this way, the child spends the whole day inside these “containers,” putting the occipital region under constant pressure as when the child is asleep in bed. Although advantageous from many points of view, the prolonged maintenance of the supine position creates a continuous pressure on the back of the head and determines a flattening on one or both sides of the skull.

It is also important to consider the natural history of PP that probably has existed for centuries, although at a lower incidence than the present one. The majority of infants with PP was probably not diagnosed or was treated with a policy of waiting. Some significant deformities persist, in some subjects, even in adolescence, and minor craniofacial asymmetries can be found in a variety of adults. Nevertheless, there are only a few cases of PP in adolescence or in adulthood as important enough to be reported.

It has been noted that the point prevalence of PPP at 1 year of age (6.8 %) has not significantly changed in the past 40 years, and it has been suggested that an increase in referral rates may be the result of increased awareness of early referral for the evaluation of infants with skull deformities, rather than an increase in prevalence [26].

The prevalence of plagiocephaly has been shown to vary with age [17]: 13 % at birth, 16 % at 6 weeks, and 19.7 % at 4 months of age (Fig. 3.3). More importantly, it has been shown that there has been a large increase in the number of cases of plagiocephaly being seen in the last 15 years. This increase in plagiocephaly has been attributed to many factors: first and foremost, the institution of the Back to Sleep program in 1992 by the American Academy of Pediatrics in an effort to decrease the incidence of SIDS. In addition to this, there has been the increased use of baby seats and interchangeable car seats, leaving kids on their backs for a longer period of time during the day. It is also thought that there may just be an increased awareness of plagiocephaly by doctors and parents so they are referring children more than before.

Fig. 3.3

The incidence of PPP is striking at 6 weeks of age, increases to a maximum at 4 months, and then slowly decreases over 2 years because most cases resolve in that time [30]. A cohort study has shown that the incidence of PPP is 16 % at 6 weeks, 19.7 % at 4 months, 6.8 % at 12 months, and 3.3 % at 24 months [18]

In 1992, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommended, after noting an increased risk for SIDS with prone and side sleeping positions, that all healthy infants be placed to sleep supine. Prior to the AAP supine sleeping recommendation, at least 70 % of infants were placed to sleep prone. Since the recommendation in 1992, only 20 % of infants are placed in the prone position, and the SIDS rate has decreased by more than 40 %. A complication of the recommended supine sleeping position, or “Back to Sleep campaign,” is prolonged pressure on the infant’s occiput, leading to an increase in the cases of positional plagiocephaly [6]. A year following the initial AAP recommendation, a 30 % increase in referrals for positional plagiocephaly was observed, as well as continued increases in subsequent years. These increases were not noted in referrals for other craniofacial anomalies. While positional plagiocephaly is a serious complication of the AAP recommendation, it is important to note that the supine position is still the favored position for healthy infants as it does successfully decrease the risk for SIDS [31].

A nearly tenfold increase in the prevalence of plagiocephaly has been recently noted in Texas, and the cause has not yet been identified [32].

Between 1999 and 2007, the most recent year for which “cleaned” state registry data were available for analysis, the prevalence of plagiocephaly rose from 3.0 cases to 28.8 cases per 10,000 live births. “This was equivalent to an average annual increase of 21.2 % per year, which is highly statistically significant” [33]. A marked increase in plagiocephaly was noted in the Texas Birth Defects Registry in recent years, with definitive diagnoses of 6,295 cases from 1999 to 2007. The registry did not distinguish congenital from acquired cases. However, the AAP recommendation “was not likely to explain our observed dramatic increase, because our study period began 7 years after the recommendation was released,” they noted.

The researchers found that the prevalence of plagiocephaly increased across all demographic groups, regardless of maternal age, maternal race/ethnicity, infant sex, gestational age, or the presence or absence of multiple fetuses. Moreover, the proportion of cases related to multiple gestation remained stable over time.

The prevalence also increased across all clinical groups studied, regardless of the severity of the deformity, whether the infant had related torticollis or oligohydramnios, or what diagnostic or therapeutic procedures were used. The mean age at diagnosis also remained consistent over time.

An analysis of data on other birth defects of the skull or face during the same period showed that all but one also significantly increased, including deformities described as “depressions in skull”; “other skull deformity”; “craniosynostosis”; “Goldenhar syndrome/hemifacial microsomia”; “hypertelorism, telecanthus, and wide-set eyes”; and “other skull or face bone anomalies.” Only “asymmetrical head” declined over time, and that decline was not great enough to account for the rise in defects described as “plagiocephaly.”

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree