Empowering Women with Disabilities to be Self-Determining in their Health Care

Kristi L. Kirschner

Judy Panko Reis

Debjani Mukherjee

Cassing Hammond

INTRODUCTION

In increasing numbers, women with disabilities are finding their way into public offices, educational institutions, health care organizations, corporate boardrooms, science laboratories, the arts, and sports arenas. They are defying the old adages of “can’t do” and invisibility and becoming authors and sculptors of their lives. With wisdom and resilience born out of years of hardship, exclusion, and prejudice, women with disabilities are finding their voices and increasingly shaping the world. They are declaring that no longer is it shameful to inhabit a body that is atypical in its anatomy or physiology or to need personal assistance services (PAS) (1). They are challenging us to question the wisdom of the drive toward homogeneity and independence with counter images and enhanced notions of diversity and interdependence as integral girders to the society of the future.

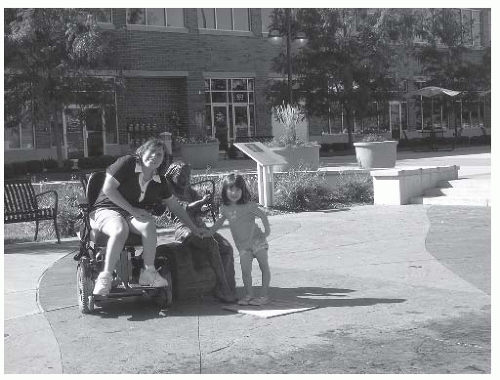

Nowhere are those voices more loudly heard than in the health care setting. Without question, in the last 20 years many social barriers have eroded. Curb cuts, accessible transportation and communication systems, and greater access to public spaces including higher education and the work place are increasingly expected “norms” in the community. Ironically, health care, a critical resource in the lives of many people with disabilities, has been one of the slowest domains to change and adapt (2, 3, 4, 5). But the pressure is on. Women with disabilities are no longer accepting second-class health care, tolerant of a denied mammogram or Pap smear because they cannot stand or get onto the examination table. No longer are they willing to endure exclusion from reproductive health care services, based upon the mythology that they, as disabled women, are asexual, childlike, and unlikely interested or able to become wives and mothers (Fig. 58-1).

This chapter is intended as a resource to help health care professionals (HCP) work in partnership with women with disabilities to meet these gender specific needs (6). We have chosen to organize the chapter around topics that affect all women with disabilities regardless of age or stage of life as well as those that are specific to particular stages of growth and development. These topics include access to health care and preventive care including breast health and cervical cancer screening, menstruation and reproductive health care issues for the adolescent girl and young adult, issues of identity and self-esteem, contraception, pregnancy, parenting issues including custody and adoption, menopause and aging with a disability, mental health, and domestic violence and abuse. Osteoporosis and sexuality, though critical topics for disabled women’s health care, are not discussed, as these topics are covered in other chapters (Chapters 39 and 51 respectively). The chapter is organized loosely around the different broad life stages, with a focus on both reproductive and psychosocial issues. Our topics represent issues that women from the disability community have told us are important to them, from their writings, conferences, research, and their collaboration with health care providers (7,8). This chapter is meant to highlight principles that will enable women with disabilities and their HCPs to advocate for the quality of care that they, as women, need.

In this chapter, the phrases “women with disabilities” and “disabled women” are both used. Language is constantly evolving and in disability communities, “… a controversy has raged over preferred linguistic usage” (9). The term “people with disabilities” underscores “the importance of the individual in society and disability as being something not inherent in the person” (9). The term “disabled people” emphasizes minority group status and pride in disability identity. Consistent with this emphasis on disability as a social minority identity and not only a medically defined deficiency, the authors of this chapter have chosen to use these terms interchangeably.

BARRIERS TO HEALTH CARE

People with disabilities are no strangers to barriers (Table 58-1). The most overt barriers are physical such as stairs, narrow doorways, curbs, and inaccessible bathrooms (6,10, 11, 12). Another type of physical barrier is inaccessible medical equipment, such as examination tables, bariatric scales, and mammogram machines. Communication barriers include lack of sign language interpreters, materials in Braille, large print, or on computer disk. Programmatic barriers encompass lack of trained physical assistance, inflexible scheduling, and transportation difficulties. Economic barriers also play a significant role in preventing people with disabilities from accessing community services, such as health care (13). The most insidious barriers, however, are erected by ignorance and negative social attitudes

about life with disability (9). Women with disabilities, in particular, are disproportionately affected by discriminatory practices in employment, education, vocational services, economic programs, access to benefits and services, health care, and parenting activities (14,15). With the passage of civil rights laws such as the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) in 1990, and expanding clinical services targeting the needs of women with disabilities, this situation is beginning to improve (16,17). We are a long way, though, from full integration, where a woman with a disability can go to a community health center with the expectation that it will be fully accessible with wheelchair-adapted equipment and knowledgeable staff trained to assist women with a variety of disabilities in a manner respectful of their womanhood (Fig. 58-2).

about life with disability (9). Women with disabilities, in particular, are disproportionately affected by discriminatory practices in employment, education, vocational services, economic programs, access to benefits and services, health care, and parenting activities (14,15). With the passage of civil rights laws such as the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) in 1990, and expanding clinical services targeting the needs of women with disabilities, this situation is beginning to improve (16,17). We are a long way, though, from full integration, where a woman with a disability can go to a community health center with the expectation that it will be fully accessible with wheelchair-adapted equipment and knowledgeable staff trained to assist women with a variety of disabilities in a manner respectful of their womanhood (Fig. 58-2).

The unequal representation of women in health care research is another barrier to health care facing women with disabilities (18,19). Historically, women have often been excluded from medical research for a variety of offered reasons ranging from methodologic issues about the menstrual cycle to liability concerns related to potential pregnancies (20). As a result, we have had little information about the causes and most effective treatment for major diseases of women such as coronary artery disease, the number one killer for both genders (21,22). The Women’s Health Initiative of the National Institutes of Health, launched in 1991, was a major effort to address these deficiencies with a 15-year commitment of funding for large multicenter studies on topics such as breast and colon cancer, osteoporosis, and heart disease (23). Unfortunately, women with disabilities were not identified as a subpopulation for study; thus, despite the richness of the information, it did not help answer particular questions about the similarities or the distinctions of these health issues in the context of disability.

TABLE 58.1 Access Barriers | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

DEMOGRAPHIC FACTORS

Based on the American Community Survey conducted by the U.S. Census Bureau in 2007, it is estimated that 15.5% of females over the age of 5 are disabled, 6.5% have one type of disability, and 9.0% have two or more types of disability (24). These figures are for civilians and noninstitutionalized persons. When considering the entire U.S. population, estimates are likely higher, with the most recent population-based data indicating that 21.3% of the female population has a disability, slightly higher than men (19.8%). They also tend to have more activity limitations than men with disabilities (25). Women with activity limitations are less likely to be married compared to other women and men with or without activity

limitations. There is evidence that severity of disability plays a role. Only 44% of women with “severe” activity limitations (unable to carry on a major activity for their age group such as work, independent living, attending school, etc.) are married, and these women have higher rates of divorce than women with less severe limitations (26). About a third of women with disabilities have children at home, compared to about a quarter of men with disabilities (27).

limitations. There is evidence that severity of disability plays a role. Only 44% of women with “severe” activity limitations (unable to carry on a major activity for their age group such as work, independent living, attending school, etc.) are married, and these women have higher rates of divorce than women with less severe limitations (26). About a third of women with disabilities have children at home, compared to about a quarter of men with disabilities (27).

TABLE 58.2 Employment and Poverty Comparison, American Community Survey, U.S. Census Bureau, 2007 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

In general, women’s education level is inversely related to degree of disability (25). Women with disabilities are more likely to live in poverty, be unemployed, or if they are employed make less than either women without disabilities or men (Table 58-2). Women with disabilities are as likely as nondisabled women to have health care coverage but are more likely to have publicly funded coverage (as opposed to private insurance) than nondisabled women (13).

HEALTH DISPARITIES

The burgeoning literature on health disparities underscores that women with disabilities are subject not only to economic barriers but also to the lack of access to health care (2,5,28). The data on access is not straightforward, however. For example, in a recent analysis of a national probability sample (29), researchers examined health care access using eight measures including sources of care, insurance status, satisfaction, Papanicolaou test, and breast exam. They conclude that, “although the women with disabilities had similar or better potential health care access than nondisabled women, they generally had worse realized health care” (29). More specifically, women with disabilities were more likely to postpone care and medications and were less satisfied with their medical care than women without disabilities, although they had higher rates of a “usual source of health care.” In a longitudinal study of medical expenditure survey data (30), disabled women were less likely to receive Pap smears, mammography, and other cancer screening services but more likely to receive influenza immunization, and colorectal and cholesterol screening. Furthermore, there were significant socioeconomic and racial differences in access. The authors conclude that disability is a barrier to preventive clinical services and “a key issue for improving women’s health care is to identify those who are at risk for specific measures of preventive care and also recognize subgroup disparities in care” (30).

These findings regarding health disparities in reproductive health care screening (e.g., Pap smears and mammograms) have been replicated by others including a study of women with major mobility impairments who were compared to their nondisabled counterparts (31). In addition, it appears that the severity of disability inversely correlates with the likelihood of receiving Pap smears and mammograms for women with physical disabilities (32). Furthermore, disparities for women with severe impairments appear to be exacerbated by a variety of factors including lack of knowledge on the part of health care providers, systems issues, ineffective communication, and lack of access to health information and services (33).

There is growing evidence of health disparities in the treatment phase of an illness and not just in health care screenings. In a retrospective observational study of women with stage I to IIIA breast cancer, those with disabilities were much less likely than other women to receive radiotherapy following breast conserving surgery than nondisabled women (34). Many reasons are posited for such disparities, ranging from absent or inadequate health insurance, patient preferences, lack of physical access or transportation resources, and attitudinal bias. Further research is needed to uncover the causes for these health disparities.

REPRODUCTIVE HEALTH CARE

Women with disabilities overwhelmingly report difficulties obtaining balanced information about reproductive health care issues, techniques for managing menstruation, birth control, risks associated with pregnancy, techniques for labor and delivery, information about sexual functioning, dating, gender identity, etc. (1,35,36). Consistent with the rehabilitation model, it is our recommendation that the physiatrist works with a team of HCPs, including obstetrician/gynecologists,

urologists, anesthesiologists, and allied health professionals, who are committed to delivering knowledgeable, respectful, and accessible reproductive health care services to women with disabilities. What follows are some general suggestions and tips to help optimize the access to needed reproductive and preventive health services for women with disabilities.

urologists, anesthesiologists, and allied health professionals, who are committed to delivering knowledgeable, respectful, and accessible reproductive health care services to women with disabilities. What follows are some general suggestions and tips to help optimize the access to needed reproductive and preventive health services for women with disabilities.

Preventive Health Care Services: Pap Smears and Gynecologic Examinations

Basic preventive health and gynecologic screening for women with disabilities is often overshadowed by more obvious physical or neurological problems, which may require more immediate focus (37). Thus, screening for diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and thyroid imbalance, all of which are common concerns for women, may be neglected in women with disabilities. Many women avoid gynecologic care because of difficulty in obtaining an accessible, comfortable, and dignified examination (1,36,38). As a consequence, treatable earlystage problems may escalate and become much more difficult to manage. These concerns include Pap smear screening as well as breast evaluation.

Performance of the pelvic examination must be tailored to a woman’s physical impairments often through the use of creative positioning techniques (39,40). An accessible examination table that lowers to wheelchair height and has security features such as hand rails, boots, and straps can be indispensable (39). Leg adjustments should be performed slowly and gradually to minimize pain and spasticity. Liberal application of lidocaine gel to the perineal area can be helpful in minimizing spasticity or in preventing episodes of autonomic hyperreflexia (AH) in some spinal cord injured women with high lesions (above T6) (41).

Preventive Health Care Services: Breast Self-Exam and Mammograms

As of 2004, breast cancer afflicted 126.4 per 100,000 women/year, making it the most prevalent gynecologic cancer occurring in women (42). Currently, it is estimated that one in eight women will develop breast cancer. As a screening tool, mammography detects 80% to 90% of breast cancers. While there is general agreement that all women of age 50 and older should have yearly screening mammograms, there is still no clear consensus regarding women between the ages of 40 and 49 (43). Women with disabilities should, at the very least, obtain screening mammography at rates comparable to nondisabled peers.

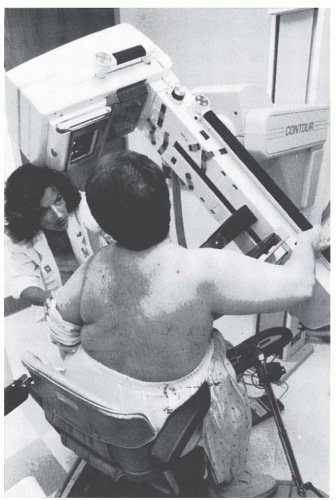

Unfortunately, many facilities utilize equipment unable to easily accommodate mobility-impaired women. Though universal design mammography equipment is available, not all mammography centers or technicians are knowledgeable about how to accommodate women with disabilities. There are ongoing efforts to educate breast health providers about how to ensure that women with disabilities are accommodated (44, 45, 46). Women with disabilities should ask their health care provider for the names of facilities in their area best able to accommodate their disability and should contact the center in advance to notify them of any special needs they might have. Although many authorities dispute the value of the breast self-exam and have muted prior calls for its monthly performance (47), many women informally check their breasts after their menses or at a regular interval in order to report any concerning changes (48). Women with disabilities, particularly those lacking manual sensation or dexterity, might need to rely on a partner or personal attendant to assist with this examination.

REPRODUCTIVE AND HEALTH ISSUES FOR ADOLESCENT GIRLS AND YOUNG ADULTS

Management of Menstruation

Menarche is a symbolic moment in most women’s lives, marking the transition from “girlhood” to “womanhood,” with the attendant procreative possibilities. For young girls growing up with their disabilities, it can also bring a host of stresses—from the practicalities of managing menstrual hygiene to the parental anxieties and concerns raised by menstruation (49, 50, 51, 52). Parental discomfort can encompass a wide range of issues: the need to assist with menstrual hygiene; concerns about menstrual cramps and painful periods (particularly for those daughters with intellectual or communicative disabilities); maturation and secondary sexual characteristics of their daughters with awareness of vulnerabilities for sexual abuse; interest in dating and sexuality; and potential pregnancy. The recent Ashley X case, which involved a novel growth attenuation treatment for a young girl with “static encephalopathy,” also raised the issue of the parental concerns about their daughter’s future care, particularly as they contemplated the maturation of her body from a lightweight young girl easily portable by family members to an adult woman’s body (50, 51, 52). The report of the growth attenuation treatment sparked much controversy about whether a treatment should be offered to both surgically and hormonally alter the body of children with developmental disabilities in order to make their care easier (with the belief that such an action will improve the person’s quality of life) (50). A number of disability activists and organizations have subsequently come out with strong statements against the practice (53, 54, 55).

When HCPs are faced with parental requests for sterilization or hysterectomy as a means of managing their minor child’s menstrual hygiene or concerns about future pregnancy, it is helpful to have some resources and guidelines. In general, the indications for hysterectomy and sterilization should be the same as for the nondisabled population, and other less invasive interventions should be considered to address the identified problem. The American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology Committee have issued an opinion on “Sterilization of Women, including Those with Mental Disabilities” (56), and present guidelines for consideration of these requests for both women with capacity to consent and those with cognitive disabilities who are not able to provide adequate informed consent. Given the permanency of the procedures and the possibility of coercion and abuses, many

states require that the courts be involved if a decision is made to proceed with sterilization of a minor child or woman with cognitive disability. Though the hysterectomy in the case of Ashley X was not done with the primary intent of sterilization, the case was investigated by Washington Protection and Advocacy (57). In their report, Washington Protection and Advocacy laid out some ground rules for future decision making around similar cases which included

states require that the courts be involved if a decision is made to proceed with sterilization of a minor child or woman with cognitive disability. Though the hysterectomy in the case of Ashley X was not done with the primary intent of sterilization, the case was investigated by Washington Protection and Advocacy (57). In their report, Washington Protection and Advocacy laid out some ground rules for future decision making around similar cases which included

Need to get a court order/permission before doing a sterilization procedure or growth attenuation treatment in a minor child with disability

Need to have a disability advocate involved in ethics decision making around such cases

Though the ruling is applicable to the state of Washington only, it is important to know the laws in the particular state of residency regarding sterilization procedures of minor children or disabled adults who lack decision-making capacity.

When possible, HCPs need to proactively address these issues with both girls growing up with disabilities and their parents, introducing options for managing menstrual flow if possible, before the onset of menstruation (58, 59, 60, 61); such discussions offer opportunities for girls with disabilities to develop a sense of control over their emerging sexuality and evolving images of themselves as women. For parents of girls with disabilities, the discussions offer opportunities to address their fears and concerns with balanced information, creative options, and the perspectives of the lived experience of women who grew up with their disabilities.

For women with acquired disabilities who are still menstruating, management of menstrual flow should be addressed shortly after the onset of disability, preferably as a part of a rehabilitation program. Some women may be able to work with a nurse or occupational therapist to develop a system for managing menstrual hygiene. Other women may find that switching to sanitary pads if they had previously used tampons may be all that is needed. Still other women may elect to work with a personal assistant to manage their menstrual hygiene. Some women, particularly those with more extensive physical disabilities, may find these options impractical and choose to look for pharmacological options (i.e., hormonal interventions) to regulate or curtail the menstrual flow (62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67). While there are a number of options used by women in general, there is little data on the safety and usage of these treatments in women with disabilities. Unfortunately, some physical disabilities and chronic disease states are inherently associated with menstrual irregularities, leading exactly to the unpredictable flow that is so unwelcome.

Access to Information

It is estimated that girls with disabilities (age 21 and younger) comprise 8% of female youth (25). While girls and young women with disabilities share similar health care issues with their nondisabled peers, their health encounters are likely to be more frequent, intense, and complex (68). In addition to routine adolescent health needs, disabled girls may encounter a regime of disability-specific repeated hospitalizations, health visits, and medication schedules that can intrude into their family, school, and social lives. Sensitivity to the medicalization of these girls’ lives is important and should be demonstrated by actively engaging the girls in the decision-making process as it affects their health issues. This can be accomplished in partnership with a parent or caregiver as long as the girl is not coerced into unwanted decisions and supported with information in a user-friendly format that allows her to be self-determining. The promotion of self-determination in girls and young women with disabilities serves to decrease the incidence of negative health encounters while optimizing the likelihood of compliance with healthy life choices.

Lack of access to information can prevent girls and women with disabilities from achieving self-determination in health and other aspects of life. Research suggests that “adolescents with disabilities are likely to be participating in sexual relationships without adequate knowledge and skills to keep them healthy, safe, and satisfied,” and are twice as likely to experience sexual abuse (69). Their exclusion from sources of information about sexuality and reproductive health options has been assisted by inadequate disability accommodations, negative disability attitudes, or a combination of both types of barriers (70). Many girls with disabilities grow up outside the usual channels for learning about sexuality. For example, they may be denied admission to their neighborhood schools and recreation programs due to access barriers and discriminatory enrollment practices (71). Consequently, they are denied important informal opportunities to exchange information and experiences regarding sexuality with their peers. Instead, they might be placed in a sheltered and closely supervised “special education” school where even formal sex education may not be offered. Their parents are less likely to talk to them about sexuality and reproduction than to their nondisabled sisters (68). Girls and young women who are blind are rarely given tactile anatomical models so they can safely explore and understand the form and function of human body parts. Those who are deaf or hard of hearing may miss conversations about “the facts of life” whispered between hearing friends. Girls and women with cognitive disabilities may not fully understand spoken and written information about sexuality and health matters unless it is presented in an illustrated, uncomplicated manner. There are some materials that are helpful in preparing girls and women with disabilities for their first pelvic and breast exams, such as the video and workbook “Let’s Talk About Health: What Every Woman Should Know” designed for girls with developmental disabilities (72).

In adulthood, information barriers interfere with health maintenance for women with disabilities (6,11). Blind women and those with low vision confront clinic signs, instructions, release forms, and educational materials that have not been translated into accessible formats, such as Braille, audiotape, or computer disk versions. Deaf women are not offered interpreters to insure accurate doctor/patient communication. Women with cognitive disabilities are not allowed adequate time and explanation to ensure comprehension and informed

consent. There is also evidence that physicians’ perceptions of a woman’s disability may result in the withholding of information about her health options. One of the first systematic studies to document disabled women’s health service experiences (38) revealed that physicians’ inclination to offer disabled women patients information regarding sexuality and contraception was mediated by such factors as the age of onset and extent of a woman’s disability.

consent. There is also evidence that physicians’ perceptions of a woman’s disability may result in the withholding of information about her health options. One of the first systematic studies to document disabled women’s health service experiences (38) revealed that physicians’ inclination to offer disabled women patients information regarding sexuality and contraception was mediated by such factors as the age of onset and extent of a woman’s disability.

Some reproductive health agencies, such as Planned Parenthood and Regional Family Planning, have taken important steps to ensure that their information and services are accessible to women with disabilities. State or city government offices specializing in disability services can guide physicians in providing accessible information and communication to patients with disabilities. A useful rule of thumb in working clinically with any woman with a disability, particularly early onset disability, is to ask if she would like information or guidance about sexuality, reproductive health options, or any other aspect of health. Some women with disabilities are sophisticated about their health options and the workings of their bodies; others lack basic information about anatomy and human sexuality. Many are experts regarding their particular disability but have gaps in general health maintenance knowledge due to the information barriers discussed above. It is important to explore with each woman her level of knowledge and desire for more information before concluding any health service contact.

Personality/Self-Esteem

Girls and women with disabilities are as tremendously diverse as any other category of human being. Indeed, the development of personality characteristics and life histories will influence a woman’s reaction to medical intervention, her adjustment to changes in functioning, and her coping mechanisms. In this section, we will begin by briefly reviewing personality factors—the relatively stable dispositional and relatively malleable situational variables that impact human functioning. For rehabilitation professionals, however, the research literature on experiences of marginalization, disempowerment, self-esteem, and implicit messages about what it means to be a woman with a disability are important to consider. After a general discussion of personality and self-esteem, we will summarize some research literature focused specifically on women with disabilities.

Personality psychology is a diverse area of study. McAdams and Pals (73) outline five big principles in personality theory and research: evolution and human nature, dispositional traits, characteristic adaptations, life narratives, and culture. Evolution has impacted human nature, resulting in fundamental ways in which human beings are the same. Specifically, there are some universal, cross-cultural, and historical aspects of human life which have evolved over time such as adaptation and cooperation. Sheldon (74) focused on three psychological needs: “need to sustain a basic sense of self (autonomy), to manipulate the environment in order to achieve instrumental goals (competence), and to form cooperative relationships with others (relatedness)” (73). For women with disabilities, the issues of autonomy (or self-determination), competence, and relatedness are as fundamental to their flourishing as they are for health care providers and family members who each bring their own perspectives to the medical encounter.

The second principle is the importance of dispositional traits. Dispositional traits include what has classically been referred to as the big five factors of personality: openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism (75,76). Debates within personality psychology have focused on dispositions versus situations, but there is some consensus that there are broad dimensions of human personality that account for consistency over time and differing contexts. It is these deep-seated dispositional traits that underscore the variation within women with disabilities. The third principle is characteristic adaptations. These include goals, strategies, values, schemas, and “many other aspects of human individuality that speak to motivational, social-cognitive, and developmental concerns” (73). The fourth principle is life narratives, or the life stories that individuals construct, retell, and constantly recreate to make sense of their world.

In the past several decades, research into narrative identity has opened up new ways of thinking about the self. These narratives open up room for change and also for making sense of disparate experiences, or for reframing negative experiences into more positive ones. Beyond the narrative identity that is constructed through stories that give meaning to our lives, women with disabilities have various identities that may impact their adaptation to impairments. For some women, a disability identity that focuses on pride and social structures will be prominent. For other women, ethnic identity, such as “Asian American,” may be an important way to reframe stories. For individuals who face “oppressive narratives about their social identities,” (77) alternative stories may increase their resilience to these negative narratives.

Finally, the fifth principle of an integrative science of personality is the differential role of culture. Culture can impact some aspects of our personality (e.g., narrative identity) while others may be less amenable to change (e.g., neuroticism). Furthermore, different cultures may encourage certain behaviors or ways of thinking about the world. For example, an American woman with a disability may focus on individual rights, while a South Asian woman with a disability may focus on social roles. The general discussion of personality highlights the opportunities for health care providers to tailor their health care provision with these factors in mind.

Self-Esteem and Self-Determination

The concept of self-esteem has the qualities of a personality trait and a psychological state (78) and refers to an appraisal of one’s worth. Other terms such as self-regard and self-respect have also been used in the literature. Recently, scholars have focused on specific aspects of self-esteem. For example, Crocker et al. have defined “contingencies of self-worth” or domains from which individuals derive their perception of self-worth. They describe the domains of virtue, God’s love, support of family, academic competence, physical attractiveness, gaining others’

approval, and outdoing others in competition (78). Therefore, self-esteem is contingent on the extent that an individual bases her self-worth on a specific domain, and either succeeds or fails in that domain.

approval, and outdoing others in competition (78). Therefore, self-esteem is contingent on the extent that an individual bases her self-worth on a specific domain, and either succeeds or fails in that domain.

The majority of the research on self-esteem has focused on the level of self-esteem, high or low, and the assumption has been that high self-esteem is associated with positive outcomes. Recently, researchers have suggested that the relationship may be weaker than previously assumed (79). Crocker and Park (80) further argue that “the pursuit of self-esteem interferes with relatedness, learning, autonomy, self-regulation, and mental and physical health. Pursuing self-esteem can be motivating, but other sources of motivation, such as goals that are good for the self and others, can provide the same motivation without the costs” (80).

When the HCP focuses on perceptions of self-esteem, he or she may be limiting the creative solutions to goal attainment. For example, if a woman reports low self-esteem and views this as a global construct about her worth, and the HCP is complicit in this belief, alternatives may not be suggested. Focusing on specific activities, on areas of strength, on relationships and interdependence, rather than individualistic perceptions of self-worth, may provide alternative ways of positive adaptation.

In a study focused specifically on the self-esteem of women with physical disabilities, Nosek et al. (81) assert that it is not the disability itself but the contextual, social, and emotional impact that affect the women’s sense of self. The authors state, “we learned that their self-evaluation was strongly influenced by feedback from parents and other family members, teachers and schoolmates, friends and intimate partners. The impact of this feedback about their value as women with disabilities was predominantly negative” (81). The authors also discussed the importance of activities and the various barriers, environmental and attitudinal, that negatively impacted the women. In their study comparing 475 community-dwelling women with disabilities to 406 women without disabilities, they found that women with disabilities had significantly lower self-cognition, self-esteem, quality of intimate relationships, employment, and less education. They had higher social isolation and overprotection during childhood. The authors further state, “The social environment in which women with disabilities live is primarily a hostile one, transmitting stereotypes that have existed for millennia, resulting in stigmatization and exclusion” (81).

Some young women with disabilities, however, including those with extensive physical limitations, have demonstrated resilience in the face of invalidating messages. They have developed positive self-concepts as women and have established enduring intimate relationships despite all predictions (8). Many give credit to perceptive family members who affirmed their gender roles and who facilitated their social contacts. Others, surrounded by discouragement, refused to internalize it. Seeking strong disabled women role models for support or simply finding validation from within, they have integrated their disabilities into sound and positive identities as women (68,71). Accepting disability as a familiar and “normal” part of their lives, they seem to set their own standards for what is valuable, sexually appealing, and womanly.

Self-efficacy, or one’s beliefs about her capabilities to attain goals, is also related to the construct of self-esteem. In a qualitative study of women and men that examined the perceptions of self-efficacy and rehabilitation with patients with traumatic brain injury (TBI) and stroke (82), the authors identified 11 themes that patients described as helping them engage effectively in rehabilitation. In the first domain, self, the first five themes were self-reliance, determination, independence, recognizing own improvements, and pushing one’s limits. In the second domain, others, the next three themes were external reassurance, vicarious experience, and working with professionals. In the third domain, process, the final three themes were setting goals, information needs, and making time for rehabilitation. The authors suggest that examining self-efficacy is one way to “maximize the benefit gained from rehabilitation” (82). In the outpatient setting as well, focusing on task mastery and use of vicarious experiences (e.g., peer support) may be an effective means for increasing self-efficacy and psychosocial outcomes.

Self-determination is also influenced by self-esteem. Self-determination is distinct from independence, in that someone can be physically dependent on others but be self-determining in their choices and preferences. In the psychological literature, Self-Determination Theory (SDT) (83) refers to a theory of human motivation that encompasses the concepts of perceived competence, autonomy, and relatedness. More specifically, SDT differentiates between autonomous and controlled motivations. “Autonomous regulation involves experiencing a sense of choice, a sense of full volition,” whereas controlled regulation “involves people feeling pressured or controlled by an interpersonal or intrapsychic force” (84). Autonomous motivation leads to lasting changes and positive behaviors while controlled regulation results in temporary changes. For women with disabilities, as with any other patient, HCPs have an important role to play. For example, HCPs can provide relevant feedback to encourage mastery and work toward a strong sense of relatedness which involves trusts and connection. This can lead to higher self-determination and willingness on the part of the patient to learn and adopt new strategies for health improvement (84). In general, when physicians support the concepts of self-determination in their practice, there are positive outcomes such as adherence to medications and improved physical and psychological health (85).

REPRODUCTIVE AND HEALTH ISSUES FOR WOMEN OF CHILDBEARING AGE

Menstrual Irregularity and Fertility in Women with Physical Disabilities

Women with disabilities need to be empowered to not only understand their bodies and how they work but also to direct their choices regarding reproductive health care. For some women, this may involve decisions regarding childbearing.

For most women with physical disabilities, fertility potential is preserved, and menses resemble the patterns of women without disabilities (86). In some cases, though, menstrual irregularity and fertility problems can occur. The most common hormonal imbalances found in women in general are disorders of prolactin secretion or thyroid function. Disorders of neuroendocrine function are not uncommon after TBI, though there is no clear data on the frequency with which it affects the menstrual cycle or fertility (87). In an analysis of 13 pooled studies with 809 people with TBI, the prevalence of hypopituitarism in patients at least 5 months post TBI was found to be 27.5%; with a greater prevalence found in populations with more severe injuries (88). Some groups now recommend routine screening for hypopituitarism of patients with moderate to severe TBI (88,89).

For most women with physical disabilities, fertility potential is preserved, and menses resemble the patterns of women without disabilities (86). In some cases, though, menstrual irregularity and fertility problems can occur. The most common hormonal imbalances found in women in general are disorders of prolactin secretion or thyroid function. Disorders of neuroendocrine function are not uncommon after TBI, though there is no clear data on the frequency with which it affects the menstrual cycle or fertility (87). In an analysis of 13 pooled studies with 809 people with TBI, the prevalence of hypopituitarism in patients at least 5 months post TBI was found to be 27.5%; with a greater prevalence found in populations with more severe injuries (88). Some groups now recommend routine screening for hypopituitarism of patients with moderate to severe TBI (88,89).

For women with spinal cord injury (SCI), almost all women will resume their normal cycle within the first 3 to 6 months post injury (90); about 25% of one population of women studied report increased autonomic symptoms (sweating, headaches, flushing, gooseflesh) around the menses (91). Occasionally, medications can also cause menstrual irregularities. Phenytoin and corticosteroids may affect thyroid function and ovulation; tricyclic antidepressants, antipsychotic medications, and some antihypertensive medications may also cause menstrual irregularities by affecting prolactin levels (86,92,93). Treatment of menstrual irregularities varies with age and medical condition. Pregnancy should always be considered in evaluating menstrual irregularity. Thyroid function tests and prolactin levels can be helpful in evaluating women with irregular menstrual periods (94,95). Correcting hormonal causes of menstrual irregularities can often regulate the menstrual cycle successfully and improve fertility. In short, for women who desire to conceive and are having difficulties, they need to undergo an evaluation identical to those without disabilities (96). The male partner needs to be involved in the process by providing a semen specimen for analysis, as about 40% of all couples who present with infertility problems will have a male factor contribution (96).

Abnormal bleeding can also occur with structural problems such as uterine or endocervical polyps, fibroids, cervical pathology, and vulvovaginal lesions (97). Menstrual irregularities become more common as women approach menopause. Careful gynecologic evaluation is required to determine an appropriate course of treatment. Although gynecologists frequently prescribe low dose combination oral contraceptives and other hormonal agents either to regulate menstrual flow or control vasomotor symptoms, there is no data derived from studies of women with disabilities to guide practitioners (62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67).

Contraception

The history of contraception for women with disabilities has at times been coercive and even frankly oppressive. Dating back to the early 1900s, fears of women with disabilities producing children with disabilities led to some social policies encouraging sterilization and criminalization of marriage (98,99). Other fears have checkered the reproductive history of disabled women, including the perceived inability of women with disabilities to be “good” mothers and exaggeration of health risks for women with disabilities who choose to bear children (100, 101, 102). Concerns about “physician-controlled” contraceptives, such as Depo-Provera (Upjohn, Kalamazoo, Michigan), still percolate in segments of the disability community as a result of this history and the fear that a woman’s reproductive choices might be curtailed by physicians, parents, or guardians who make decisions on her behalf (103,104). Sensitivity to this history is essential in establishing patientcentered, trusting relationships between health care providers and women with disabilities. Women with disabilities have the same right to knowledgeable information about contraception as nondisabled women and should participate in their reproductive health care decision to the fullest extent possible. Contraceptive choices may be colored, though, by the nature of the woman’s physical impairment or chronic disease condition (105). For example, a woman with impaired hand function may have difficulty using barrier methods such as the diaphragm, sponge, or spermicidal product without assistance. Problem solving with an occupational therapist, or working with the woman’s partner or personal assistant, may result in an adequate solution for the use of barrier methods. Condoms, of course, always remain an effective method if the male partner is in agreement and provide the dual benefits of contraception and protection from sexually transmitted diseases (106).

There are a rapidly growing array of hormonal options for contraception that include a variety of combination pills, progestin-only mini-pills (62), injections (e.g., Depo-Provera—depo medroxyprogesterone acetate), subdermal implants such as Implanon (Schering Plough, Kenilworth, New Jersey), transvaginal rings, such as Nuvaring (Schering Plough, Kenilworth, New Jersey), the levonorgestrel intrauterine system (Mirena; Berlex Laboratories, Inc., USA), and transdermal patches such as OrthoEvra (Ortho-McNeil Pharmaceutical, USA). For women who desire hormonal methods of contraception, information about the risks and benefits of various hormonal contraceptive options in women with disabilities is limited. For example, some women with mobility limitations (such as women with spina bifida, SCI, and multiple sclerosis [MS]) might have an increased risk for developing thrombotic events when using combination oral contraceptives, but definitive statistics are not available (105). Woman with a history of thrombotic or thromboembolic stroke should probably avoid estrogen containing contraceptives (105). There is some indication that there may be a protective effect between oral contraceptives and rheumatoid arthritis, but the results thus far are inconclusive (105). The progestin-only contraceptive pills are associated with an increased risk of abnormal uterine bleeding and are less effective than the combination pills (62). Depo-Provera, an injectable form of progesterone that is effective for at least 12 weeks, is highly effective, and patients are often pleased with the decreased menstrual flow or amenorrhea that results from this method (107,108). Many women experience some weight gain and have reduced estrogen levels, which can lead to osteopenia (109). Indeed, Cromer et al. (110)

documented a 3% loss in bone mineral density among adolescent girls who should typically have experienced a 9% increase in bone mineral density. Concerns regarding how prolonged use of Depo-Provera might impact peak bone mineral density and subsequent risk for osteoporosis later in life prompted Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to issue a “black box warning” in 2004 (111). For women with disabilities who often confront an elevated risk of both osteopenia and osteoporosis due to chronic immobilization, this consideration is particularly important and providers should use caution when prescribing this for more prolonged periods of time.

documented a 3% loss in bone mineral density among adolescent girls who should typically have experienced a 9% increase in bone mineral density. Concerns regarding how prolonged use of Depo-Provera might impact peak bone mineral density and subsequent risk for osteoporosis later in life prompted Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to issue a “black box warning” in 2004 (111). For women with disabilities who often confront an elevated risk of both osteopenia and osteoporosis due to chronic immobilization, this consideration is particularly important and providers should use caution when prescribing this for more prolonged periods of time.

Implanon (Schering Plough, Kenilworth, New Jersey), an etonogestrel containing subdermal implant, has been available worldwide since 1998 and in the United States since 2006. Unlike Norplant, a six-rod levonogestrel implant previously available in the United States, Implanon consists of only one 4 cm, plastic rod implanted at the biceps-triceps junction of the nondominant arm. Placement consists of a minor procedure that resembles receiving an injection. Removal is far less problematic than encountered with Norplant. Approximately 10% of women discontinue Implanon due to irregular bleeding and many other patients note occasional breakthrough bleeding (112). This might present a hygiene issue for women with chronic immobility impairments. Limited data are available to assess pharmacokinetic changes among Implanon users taking other medications that induce hepatic microsomal enzymes. Although pregnancy associated with Implanon is rare, several pregnancies reported with its use occurred in women using carbamazepine or other enzyme-inducing agents (113). Fortunately, the implant exerts little impact on bone mineral density and contains no estrogen.

OrthoEvra is a transdermal patch applied weekly on the buttocks, abdomen, upper torso, or outer arm. Approved in the United States in 2002, OrthoEvra offered a novel method of delivering hormones, contained in combination oral contraceptives, for patients unable to swallow a pill or who could not remember to take a daily pill. FDA issued “updated labeling” in 2005 following reports of venous thromboembolism (VTE) associated with its use (114). Risk of VTE typically correlates with estrogen dose, and 3 weeks’ of patch use exposes patients to roughly 71% more estrogen (“area under the curve”) than ingestion of a low-dose oral contraceptive (115). Although the absolute risk of VTE remains small among users, patients at elevated risk of VTE, including chronically immobilized patients, should likely forego its use until more data becomes available.

Nuvaring is a flexible, transparent ring placed in the vagina 3 out of 4 weeks/month. Indications and contraindications to the ring resemble traditional oral contraception. Unlike the OrthoEvra Patch, Nuvaring exposes women to less estrogenic exposure than either the patch or pills while providing superior cycle control (115). Women with disabilities might find it difficult to check for the ring’s presence in the vagina, particularly after intercourse when the vagina physiologically dilates and may need the assistance of their partners to do so. Women with denervation atrophy and relaxation of the pelvic floor might also have difficulty retaining the ring and approximately 5% of women discontinue the ring due to “ring-related” issues such as vaginal discharge.

Intrauterine devices (IUD) represent the most popular form of reversible contraception throughout much of the world but remain underutilized within the United States. Despite contraceptive efficacy that approaches that of surgical sterilization, many clinicians still fear infectious and other risks previously attributed primarily to shield type IUDs (116

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree