Chapter 51 Drug Abuse

Scope of the Problem

The prevalence of illicit drug use varies by race and ethnicity. Illicit substance use was highest among people reporting two or more races, at 14.1%. An estimated 10.1% of blacks, 9.5% of American Indians or Alaska Natives, 8.2% of whites, 7.3% of Native Hawaiians or other Pacific Islanders, 6.3% of Hispanics, and 3.6% of Asians were current illicit drug users in 2008. Illicit drug use also varies by education level. Among adults age 18 or older, the prevalence of current illicit drug use was 9.4% of adults with some college education, 8.1% of adults who did not complete high school, 8.6% of high school graduates, and 5.7% of college graduates. In 2008 an estimated 8000 people used an illicit substance for the first time each day. Most initiates were female and younger than 18. Between 2003 and 2008, the number of daily new users of cocaine, psychotherapeutic drugs and inhalants had decreased. During the same 5-year interval, the number of people initiating use of hallucinogens, ecstasy, and LSD had increased significantly. Approximately, 19.6% of unemployed individuals age 18 and older were current illicit drug users. This was significantly higher than the prevalence of current drug use among individuals employed full time (8.0%) and part time (10.1%).

Terminology

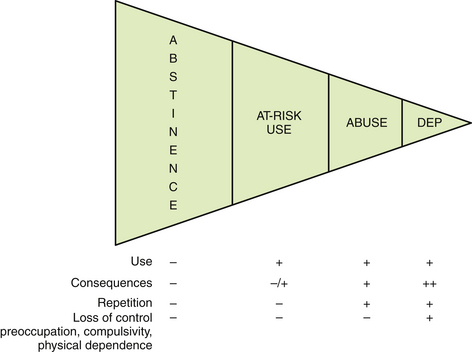

The term “substance use disorder” (SUD) implies a continuum of use: from abstinence to at-risk use to abuse and dependence (Fig. 51-1). The majority of the general population, as well as family medicine patients, are “abstainers.” The majority of users of illicit substances do not meet criteria for the diagnosis of abuse and dependency. This model of substance use is important for family medicine physicians to keep in mind as they talk with their patients about substance use issues. It highlights the key role played by screening for substance use and early intervention at the at-risk use level, before specialized treatment services are more likely needed. For illicit substances, unlike alcohol, no amount of use can be considered safe or healthy, in part because any use is illegal.

Figure 51-1 Continuum of drug use in patients with substance use disorders.

(Modified from Association for Medical Education and Research in Substance Abuse.)

Box 51-1 lists the DSM IV diagnostic criteria for substance abuse and dependence. Of note, physical dependence alone does not make a diagnosis of substance abuse or dependence, nor does lack of physical dependence exclude the diagnoses.

Box 51-1 Diagnostic Criteria for Substance Abuse and Dependence (DSM IV)∗

Abuse

Dependence

Three or more of the following, occurring in the same 12-month period:

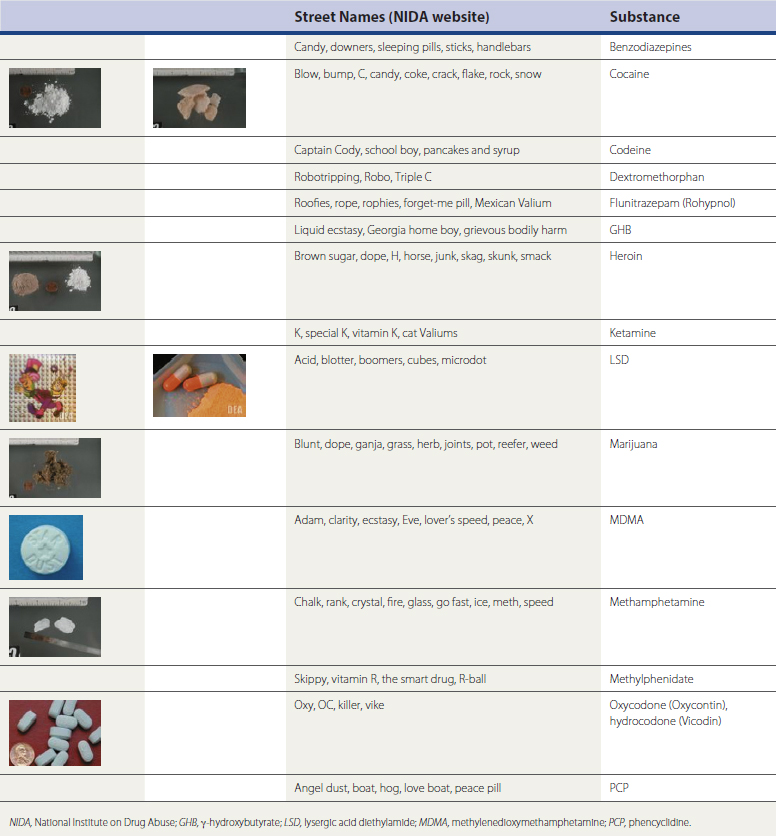

Table 51-1 shows some common drug street names. Comprehensive lists can be found on the Office of National Drug Control Policy website, www.whitehousedrugpolicy.gov. Street names vary by region and user group. The most useful information is obtained on the local level, simply by asking patients what they call the drug they are using.

Screening

With the recent increase in prescription drug misuse and abuse, interest in drug-use SBIRT incorporation into primary care has broadened and is being studied for efficacy (Insight Project, 2009). Limitations on drug-use SBIRT in primary care include lower prevalence of drug use in primary care patients compared with alcohol use as well as concerns about the practicality of use and positive predictive value (PPV) of available screening instruments in the primary care setting. The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), the Bright Future Initiative, and American Medical Association (AMA) Guidelines for Adolescent Preventative Services (GAPS) all recommend at least annual screening of adolescents for drug use. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) advocates regular, periodic screening for all patients, regardless of pregnancy status, although no specific screening instrument is recommended and, to date, no screening instrument has been validated for pregnant women (Lanier and Ko, 2008). Common validated screening instruments for drug use are briefly discussed below.

The CRAFFT is the only screening instrument validated for adolescents and has shown an 83% PPV (Table 51-2). It screens for alcohol as well as drug use (Knight et al., 2002).

Table 51-2 CRAFFT Screening Tool for Adolescents

| CRAFFT | Question |

|---|---|

| Car | Have you ever ridden in a car by someone (including yourself) who was “high” or had been using alcohol or drugs? |

| Relax | Do you ever use alcohol or drugs to relax, feel better about yourself, or fit in? |

| Alone | Do you ever use alcohol or drugs while you are by yourself, or alone? |

| Forget | Do you ever forget things you did while using alcohol or drugs? |

| Friends | Do family members or friends ever tell you that you should cut down on your drinking or drug use? |

| Trouble | Have you ever gotten into trouble while you were using alcohol or drugs? |

Scoring:

A “no” response = 0 points; a “yes” response = 1 point.

0-1 point = negative screen.

2-6 points = positive screen; consider a safety contract for “yes” response to “car” question regardless of total score.

The CAGE-Adjusted to Include Drugs (CAGE-AID) has shown 12% to 78% PPV, with PPV increasing with increasing prevalence of drug use in the study population (Brown and Rounds, 1995). It screens for both alcohol and drug use (Table 51-3).

Table 51-3 CAGE-AID Screening Tool for Adults

| CAGE | Question |

|---|---|

| Cut down | Have you felt you ought to cut down on your drinking or drug use? |

| Annoyed | Have people annoyed you by criticizing your drinking or drug use? |

| Guilty | Have you felt bad or guilty about your drinking or drug use? |

| Eye opener | Have you ever had a drink or used drugs first thing in the morning to steady your nerves or to get rid of a hangover (eye opener)? |

Scoring:

A “no” response = 0 points; a “yes” response = 1 point.

0-1 point = negative screen.

2-4 points = positive screen.

Patients screening positive receive more in-depth screening with a self-administered or provider-administered screening instrument, such as the DAST or ASSIST, which both allow for stratification of each patient along the SUD continuum. The physician then scores the formal screen and reviews the results with the patient. Patients screening negative are given brief feedback about the results of their screen, and their healthy choices regarding substance use are reinforced by the physician. Patients screening positive for at-risk use, but who do not meet criteria for abuse or dependence, receive a brief intervention, often using the FRAMES model (Box 51-2) or the “Five A’s” model (Box 51-3). Both are useful for patients receptive to change. Motivational interviewing techniques may be more useful than the FRAMES or Five A’s techniques for patients who are more ambivalent about change (Searight, 2009).

Laboratory Testing

Laboratory testing is frequently used in SUD screening, treatment, and monitoring for relapse. The most common testing method is the urine drug test. Other options include blood, sweat, hair, and oral fluid testing. Table 51-4 lists the advantages and disadvantages of each method (Ries et al., 2009).

Table 51-4 Drug-Testing Methods: Advantages and Disadvantages

| Test | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| Blood | Difficult to adulterate; detects very recent ingestion | Invasive; drugs clear blood more quickly after ingestion than urine |

| Hair | Noninvasive; difficult to adulterate; detects patterns of use over time; frequently used in forensics and research | Not useful for recent ingestion; more difficult to process than other methods |

| Oral fluids | Noninvasive; direct observation easy and makes adulteration more difficult; detects recent ingestion; rapid results | Unintentional contamination from recently ingested substances; drugs clear quickly after ingestion (see Urine) |

| Sweat | Noninvasive; uses patch for collection; monitor for use over extended period | Quantification of drug levels difficult |

| Urine | Noninvasive; rapid results; relatively inexpensive vs. other methods | Easy to adulterate sample, even when observed collection method used |

Table 51-5 details typical detection times and causes of false-positive results for drugs that can be detected by readily available urine drug testing. Most urine drug tests use immunoassays because these are inexpensive, fast, and easily automated. Gas chromatography with mass spectroscopy (GC/MS) is typically reserved for confirmation of a positive result. Methadone is not a part of most urine drug screen panels and does not show as a positive opiate test. Separate testing for methadone is available. Separate testing is also needed for most “club drugs,” including 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA), ketamine, and γ-hydroxybutyrate (GHB). Benzodiazepines have a wide range of potencies, half-lives, and metabolites, which makes urine drug screen results less reliable (Ries et al., 2009).

Table 51-5 Urine Drug Testing: Detection Times and Drugs Causing False Positives

| Drug | Detection Time | False-Positive Result |

|---|---|---|

| Amphetamines, methamphetamine | 1-3 days | Bupropion, chloroquine, chlorpromazine, ephedrine, labetalol, phenylpropanolamine, propranolol, pseudoephedrine, ranitidine, selegiline, trazodone, tyramine, Vick’s inhaler |

| Barbiturates | Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|