Chapter 49 Driving and related assistive devices

Either a DRS or a CDRS can evaluate a client to determine whether the client is a candidate for driving. Once this determination has been made, a DRS or CDRS can recommend the type of adapted driving equipment that will best meet the client’s needs. Choosing the appropriate vehicle to modify and installation of the adaptive equipment are done in partnership with a vehicle modifier who is a member of the National Mobility Equipment Dealers Association (NMEDA). It is through the teamwork of this group of professionals that the needs of the client can best be met.

Driver evaluation

Clinical evaluation

Physical/functional ability

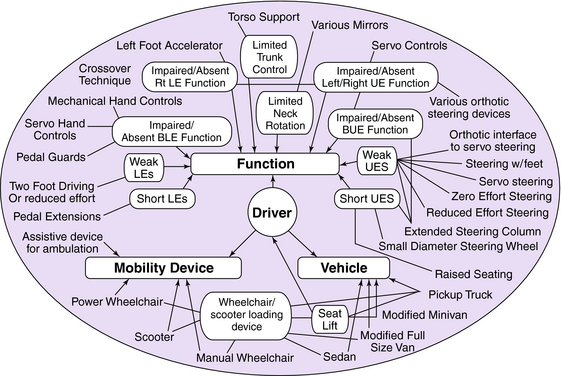

In addition, the DRS should assess the client’s ability to transfer independently to the vehicle. If the client uses a mobility device, such as a scooter or a wheelchair, the DRS should assess the client’s ability to load and unload his or her mobility device into a vehicle independently. All of these factors will influence the DRS’s selection of method and any equipment to be used for the on-the-road evaluation. (Please refer to chart Fig.49-1 on function/mobility needs/vehicle for how these areas all must be considered when looking at driving). Physical function will also help determine the proper route and traffic level during the on-the-road evaluation.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>