Double-Tapered Primary Stems

Thomas P. Schmalzried

INTRODUCTION

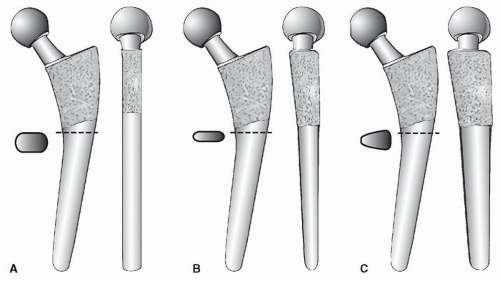

Tapered femoral stems can be described by their geometry: single taper, double taper, and triple taper. Single-taper stems have a reduction (taper) in medial-lateral dimension in the frontal plane but have a constant anteroposterior dimension. Double-taper stems have tapers in the frontal plane and sagittal plane. Triple-taper stems include a reduction in anteroposterior dimension through the cross section of the stem from lateral to medial (the third taper), in addition to tapers in the frontal and sagittal planes (Fig. 17-1). Tapered femoral stems can also be described by their surface finish or coating: grit-blasted, hydroxyapatite (HA), plasma spray, or porous ingrowth. The stems vary in the degrees of tapering as well as their length. There are also differences in neck-shaft angle and/or offset. Virtually, all cementless tapered stems are made from titanium alloy because of its biocompatibility and relatively low stiffness. While there are debates regarding the benefits and trade-offs of various design variables, the tapered stem class has been clinically successful over three decades.

INDICATIONS

Absent severe osteoporosis, the intercortical geometry of the proximal femur has a tapered shape in the frontal plane, which allows a satisfactory fit in most femurs with a similarly shaped stem. Tapered stems load the endosteal bone in compression, and the “wedge fit” offers good initial stability, which generally leads to long-term fixation through osseointegration: bone ongrowth or ingrowth. The surgical preparation of the proximal femur for a tapered stem is straightforward. For these reasons, stems with a tapered geometry are currently utilized more than any other type.

A tapered cementless stem is indicated for end-stage osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, avascular necrosis of the femoral head, femoral neck fracture, and conversion of a hip resurfacing to a total hip. Primary tapered stems can be used in revision cases when there is minimal damage to the femoral metaphysis (Paprosky type I). There are tapered stems for revisions, which are addressed in Chapter 28.

CONTRAINDICATIONS

A tapered stem should not be used if there is deficiency or deformity of the proximal femur that precludes seating or does not provide sufficient support of the implant. Axial and rotational stability must be achieved at the time of implantation for osseointegration to occur. Osteoporosis is not, in and of itself, a contraindication to a cementless tapered stem (1,2,3). The shape of the femur may be more important than bone density, and it may be difficult to get adequate initial stability in some femurs with a true “stovepipe” geometry. If the bone in the femoral metaphysis is not viable, such as with postirradiation necrosis, a cementless tapered stem should not be used.

PREOPERATIVE PREPARATION

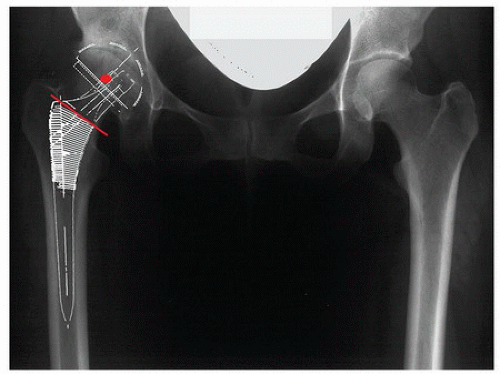

Preoperative radiographs need to show all of the femur that will be occupied by the stem in both the AP and lateral planes. It is recommended that templating be performed on a low AP pelvis x-ray to facilitate assessment of limb length and offset (Fig. 17-2). Acetabular templating is done first since the acetabular component establishes the center of rotation of the arthroplasty. The primary goal is obtaining adequate bony support for the component. For most cases, a target of 45 degrees of abduction is satisfactory. The acetabular tear drop is a consistent reference for the medial wall. An adequately sized acetabular component will approach the medial wall and be supported by superolateral bone.

For femoral templating, separately consider the part of the component inside the bone (the fit of the stem), from the part outside the bone (the neck and head), that determine the biomechanics of the reconstruction. An appropriately sized tapered femoral component may or may not be canal filling but fits the metadiaphyseal region (Fig. 17-2). The vertical position of the template on the radiograph influences the location of the neck osteotomy. There are essentially two ways to make limb length adjustments: the vertical position or height of the stem inside the canal and modular femoral heads. The “neck length” of a modular femoral head influences both length (vertical component) and offset (horizontal component), while the vertical position of the stem only influences length. The vertical position of the stem determines the location of the neck osteotomy.

The limb length and offset change for the proposed reconstruction can be assessed on the templates by comparing the location of the center of rotation of the acetabulum to the location of the center of rotation of the selected modular femoral head. For the templating exercise, consider the acetabular center of rotation as a fixed reference and the femoral head center as variable. When the selected head center directly overlies the acetabular center, there is no change in the limb length or hip offset when such a plan is executed surgically. If the acetabular center of rotation is medialized, then the femoral offset will be increased by a corresponding amount. When the head center on the templating is superior to the acetabular center, limb length will be gained when the hip is reduced at surgery. When the head center is medial to the acetabular center on the template, then relative femoral lateralization (increased offset) will occur when such a plan is executed surgically.

Many tapered stems are available with more than one offset, that is, standard and high. Some systems accomplish this by changing the neck-shaft angle, with the higher offset option having a lower neck-shaft angle. Other systems maintain the same neck-shaft angle and increase offset by medializing the take off point of the femoral neck (Fig. 17-3). Together with the modular heads, these options enable the surgeon to better achieve both the desired limb length and offset for a given hip.

TECHNIQUE

Obtain adequate exposure of the proximal femur, and protect the adjacent soft tissues.

The neck resection level is determined from the preoperative templating. The lesser or greater trochanter are commonly used references.

Some distinction has been made between systems that ream the canal before progressively rasping or broaching the proximal femur and “broach-only” systems. A rasp can remove bone moving both distally and proximally in the femur, while a broach removes or compacts bone only while moving distally.

The need for any canal reaming is determined by the internal geometry of the femur and the length of the stem. When the femoral cortices are thick and the canal is small, there is a large metaphyseal flare and a relative mismatch between the size of the metaphysis and the canal (Dorr type A femur). Such proximal-distal mismatch can present a challenge to proper fitting of a cementless stem. This is less of an issue for short stems that barely engage the diaphysis, compared to longer stems designed to be centered in, and stabilized by, the diaphysis.

Some systems are designed to first ream the canal to the depth of the intended stem and then progressively rasp the proximal femur to the corresponding size. Other systems are designed to prepare the femur with a progressively enlarging rasp- or broach-only technique. However, in

cases with a proximal-distal mismatch, the tight canal and dense distal bone can lead to proximal (metaphyseal) undersizing of the stem. Undersized cementless stems have an increased risk of not osseointegrating. The surgeon must be aware of proximal-distal mismatch and consider this variable when preparing the femur. In such cases, some reaming of the canal may be necessary, even with a so-called broach-only system, to avoid undersizing of the stem.

While preoperative templating will suggest a target stem size, the best-fit stem size is determined at surgery. Using progressively enlarging rasps or broaches, the surgeon evaluates the progressive resistance to insertion and the axial and rotational stability of each rasp or broach.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree