24 The three following conditions are quite common. Both first carpometacarpal joints are frequently affected in rheumatoid arthritis and respond well to intra-articular triamcinolone. Surgery is seldom necessary but, if so, resection arthroplasty is preferred.1 The patient describes an injury to the thumb, usually overstretching. Discomfort and pain are experienced over the thenar area and the radial side of the wrist. The backward movement during extension elicits pain and is limited. The radiograph is negative.1 Arthrosis of the trapeziometacarpal joint, or ‘rhizarthrosis’, is very common. It occurs most frequently in middle-aged or postmenopausal women2,3 and affects at least 1 in 3 women over 65 and a quarter of men over 75.4 Rhizarthrosis is often bilateral and is sometimes found in association with arthrosis at the distal interphalangeal joints of the fingers.5 The aetiology is still very unclear. There is evidence that ligament laxity6 and trapeziometacarpal subluxation are important early events in the development of thumb arthrosis.7 Inspection often reveals a dorsoradial prominence of the thumb metacarpal base secondary to subluxation and osteophyte formation. Later on, adduction and Z-deformity of the thumb develop8: the first metacarpal is displaced radially and dorsally and the metacarpophalangeal joint is in a hyperextended position. The thenar muscles are atrophic. On examination, the combined extension–abduction movement is limited and extremely painful. Crepitus may be felt, especially when the joint is axially compressed and then circumducted – the ‘grind’ test.9,10 The radiographic changes in trapeziometacarpal osteoarthritis are classified into four stages, ranging from mild joint narrowing and subchondral sclerosis to complete joint destruction with cystic changes and bone sclerosis.11 The final stage shows clear signs of sclerosis of the bone, gross osteophytes and a metacarpal that is displaced radially and dorsally. However, care must be taken to base the diagnosis not only on radiographic evidence, but also on symptoms and the physical examination. Most people with radiographic evidence of degeneration of the trapeziometacarpal joint remain asymptomatic and, when questioned, only 28% will admit to pain.12 The treatment that is chosen depends on the stage of the arthrosis and the functional disability of the joint (Table 24.1). Classically, conservative treatment of osteoarthritis of the trapeziometacarpal joint includes analgesics, joint protection, strengthening exercises of the intrinsic and extrinsic muscles of the thumb, and splints.13 Surgical management is recommended to relieve intractable pain. Table 24.1 Summary of treatment of capsular disorders Later in the course of the condition, intra-articular triamcinolone can be tried. It usually has a temporary result only. An open label trial found that steroids had no benefit on carpometacarpal pain at 26 weeks,14 while a randomized controlled trial evaluating steroids against placebo injection showed that steroids had no benefit in moderate to severe trapeziometacarpal osteoarthritis at 24 weeks.15 However, the long-term results of triamcinolone are more effective when a traumatic arthritis has supervened. During the last few decades, intra-articular injections with hyaluronic acid have been promoted as a valuable alternative to intra-articular injections with steroids.16 A few open label trials17,18 found that hyaluronic acid reduced pain and improved grip strength during 6-month follow-up, and two randomized controlled trials stated ‘non-inferiority’ of hyaluronic acid compared with steroids for pain relief at 26 weeks.19,20 Indications for surgical intervention in trapeziometacarpal arthritis are similar to those for arthroplasty of most joints: persistent pain, decreased function, instability, and failure of conservative management.21,22 Surgical options vary with the stage and nature of the disease. In the early stages, trapeziometacarpal ligament reconstruction and tendon interposition procedures23–27 have been shown to provide good symptomatic relief. For severe or late-stage disease, some have advocated arthrodesis of the trapeziometacarpal joint, assuming that there is good mobility of the joints proximal and distal.28–30 Arthroplasty techniques have ranged from simple partial or complete trapeziectomy to various implant and ligament interposition and reconstructions.31,32 These techniques have been generally indicated for stage II or greater disease once conservative management has failed. The patient lies supine on a high couch. The physician takes the patient’s outstretched hand on to his or her knee, with the thumb uppermost. With one hand the joint is palpated in the anatomical snuffbox. Caution is necessary not to mistake the edge between the metacarpal bone and an osteophyte for the joint line. With the other hand, slight traction (arrow in Fig. 24.1) and ulnar deviation are needed to open the joint. If the patient relaxes properly, the joint line can be identified by a small gap, which is marked with the nail of the palpating thumb. A 1 mL syringe, filled with 10 mg triamcinolone acetonide, is fitted with a thin needle, 2 cm long. Traction is applied again. The needle enters at the marked line just proximal to the first metacarpal on the extensor surface. Care must be taken to avoid the radial artery and the extensor pollicis tendons. To avoid the radial artery, the needle should enter towards the dorsal (ulnar) side of the extensor pollicis brevis tendon. The needle is then directed at an angle of 60° to the horizontal. At about 1 cm, the tip is felt entering the joint capsule. If it strikes bone at less than 1 cm, the position is not intra-articular and should be adjusted until the tip is felt entering the joint. The injection is then given.33 With the thumb of the other hand, friction is performed parallel to the joint line. Counterpressure is taken by the fingertips on the proximal interphalangeal joints of the supporting hand (Fig. 24.2a). Friction is imparted at the joint line and parallel to it with the thumb of the other hand. Counterpressure is given with the fingers on the ulnar aspect of the patient’s hand (Fig. 24.2b). It is important to ensure that the thumb remains palmar to the extensor pollicis brevis tendon, in that the lesion lies at the anterolateral aspect of the joint. Intersection syndrome is a specific painful disorder of the forearm that is relatively common but sometimes not correctly diagnosed clinically. It has also been referred to in the literature by the terms ‘peritendinitis crepitans’, ‘oarsmen’s wrist’, ‘crossover syndrome’, ‘subcutaneous perimyositis’, ‘squeaker’s wrist’, ‘bugaboo forearm’ or ‘abductor pollicis longus syndrome’.34 Dobyns et al introduced the term ‘intersection syndrome’, an anatomical designation related to the area in which the musculotendinous junctions of the first extensor compartment tendons (abductor pollicis longus and extensor pollicis brevis tendons) intersect the second extensor compartment tendons (extensor carpi radialis longus and extensor carpi radialis brevis tendons), at an angle of approximately 60° (Fig. 24.3).35 The most plausible pathophysiology is that of a peritendinitis at the intersection of the two tendinous compartments, which spreads upwards to the musculotendinous junction. The lesion may also lie somewhat more proximally in the muscle bellies; hence the name, ‘myosynovitis’.36 This is shown by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings demonstrating the presence of peritendinous oedema concentrically surrounding the second and the first extensor compartments, beginning at the point of crossover, 4–8 cm proximal to the Lister tubercle and extending proximally.37 The lesion always results from occupational overuse or after unusual effort. It is often associated with sports-related activities, such as rowing,38 canoeing, playing raquet sports, horse riding and skiing.39,40 After an initial stage involving a great deal of pain and disability, the condition may evolve towards a more chronic state. Spontaneous cure may take many months and only occurs when the patient gives the wrist complete rest. Treatment with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, immobilization and infiltration of steroid or local anaesthetic does not always lead to swift, full and permanent recovery. Deep transverse friction, however (three times a week, over 2 weeks), is extremely successful in this condition, to such a degree that all other treatments must be considered obsolete. This view was confirmed by Paton in 1978,41 who had used deep transverse friction since 1947 without failure. Bisschop describes 62 cases – 48 men and 14 women – that he treated between 1975 and 1982. The onset was recent (less than 6 weeks) in 55 cases and chronic (2.6 months on average) in 7. Forty-eight of the patients received other treatments, with poor results: steroid infiltration in 16 cases; local anaesthetic infiltration in 4; plaster immobilization in 13 (average 1.8 weeks); partial immobilization with tape in 2; ice friction in 4; physiotherapy in 9. Deep transverse friction – performed three times a week for 15 minutes – led to complete recovery in all but one case, with an average of 6.7 treatments, and 39 patients improved from the first treatment onwards.42 The patient’s forearm rests in pronation on the couch, the hand over its edge. With the contralateral hand the therapist brings the patient’s wrist and thumb into flexion (Fig. 24.4). This stretches the tendons. The other hand takes hold of the patient’s wrist; the thumb then lies flat on the site of the lesion. Fritz de Quervain, a Swiss physician, is given credit for first describing this condition in a report of five cases in 1895.43 The disorder has since been known as de Quervain’s disease, tenovaginitis stenosans or styloiditis radii.44 Although the term ‘stenosing tenosynovitis’ is frequently used, the pathophysiology of de Quervain’s disease does not involve inflammation. On histopathological examination, de Quervain’s disease is not characterized by inflammation, but by thickening of the tendon sheath and most notably by the accumulation of mucopolysaccharide, an indicator of myxoid degeneration.45 Therefore de Quervain’s disease should be seen as a result of intrinsic, degenerative mechanisms rather than extrinsic, inflammatory ones. The term ‘styloiditis radii’ is also a misnomer as the lesion is not bony or periosteal. Incidence of de Quervain’s disease has risen considerably in recent decades.46 It occurs mostly in women, with an average age of 47, and almost never appears before the age of 30.47 A significant association was noted in patients with de Quervain’s disease after pregnancy.48 The cause is presumed to be endocrine in origin and similar to the carpal tunnel syndrome described during pregnancy and the lactating postpartum period.49 Very often de Quervain’s disease comes on spontaneously, but it can also result from overuse. Swift repeated movement with exertion of considerable strength is a possible cause.50

Disorders of the thumb

Disorders of the inert structures

Rheumatoid arthritis

Traumatic arthritis

Arthrosis

Treatment

Deep friction

Intra-articular injection

Surgery

–

Rheumatoid arthritis

Rheumatoid arthritis

Traumatic arthritis

Traumatic arthritis

–

Early arthrosis

Moderate arthrosis

Severe arthrosis

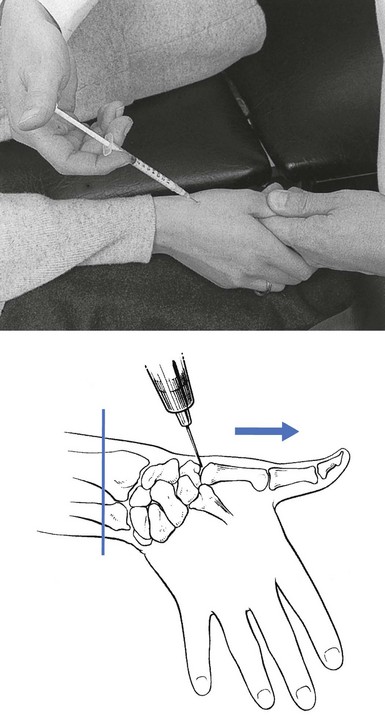

Technique: intra-articular injection

![]()

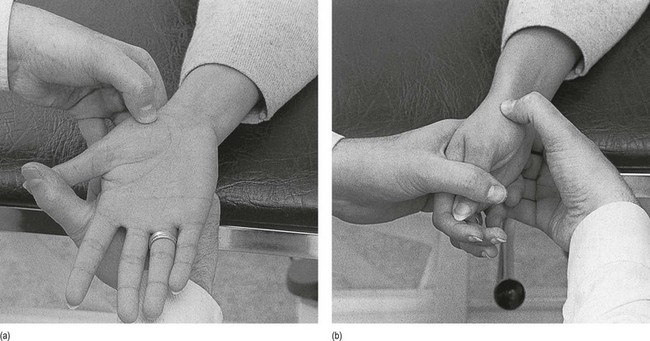

Technique: deep transverse friction to the anterior capsule

![]()

Technique: deep transverse friction to the anterolateral capsule

![]()

Disorders of the contractile structures

Pain

Resisted extension

Abductor pollicis longus, and extensor pollicis brevis (first tendon sheath)

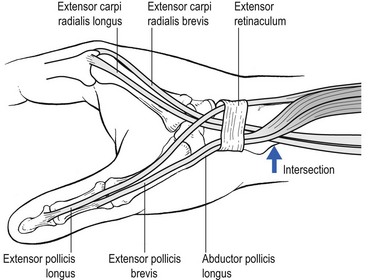

Intersection syndrome

Technique: deep transverse friction

![]()

Tenovaginitis of the first compartment

Mechanical tenovaginitis

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree