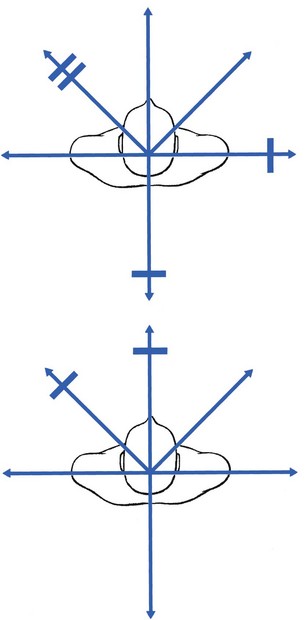

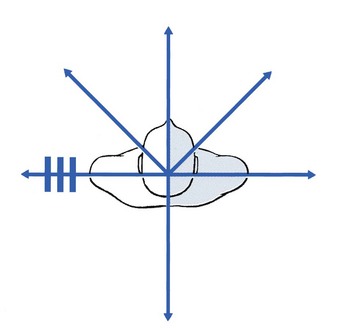

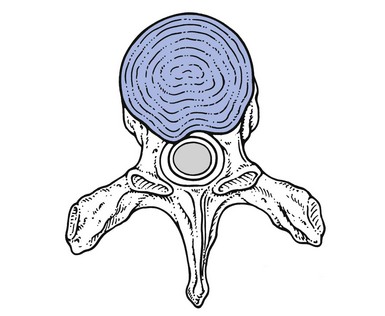

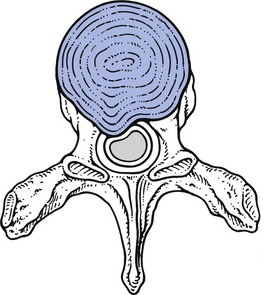

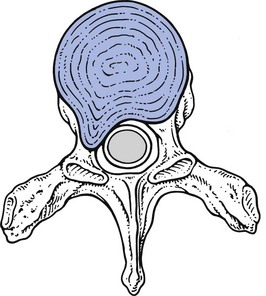

27 Although the spine is anatomically part of the thoracic cage, we prefer to discuss the thoracic disorders in two main categories – spinal lesions (this chapter and Ch. 28) and lesions of the thoracic cage and abdomen (see online chapter Disorders of the thoracic cage and abdomen). Thoracic ankylosing spondylitis is discussed separately (Ch. 29). This is done to standardize the discussion of the spine throughout, in the hope that a better clinical understanding may result. Cervical and lumbar disc lesions are widely accepted as common causes of pain. For the thoracic spine, the situation is different. Although thoracic disc lesions giving rise to compression of the spinal cord are well recognized,1–5 disc protrusion resulting in pain without causing neurological signs is poorly documented.6 The incidence of thoracic disc lesions affecting the spinal cord is about one case per million people per year,3,7 usually affecting adults, although cases have been reported in children as young as 12.8 The existence of minor thoracic disc lesions provoking pain in the absence of cord compression was first established by Hochman, who removed a disc protrusion at T8–T9 in a 67-year-old lady with continuous unilateral pain in the thorax.9 Neurological signs were not present. The diagnosis was established by computed tomography (CT). The incidence of minor thoracic disc lesions is much higher. Degenerative changes of the thoracic spine are observed in approximately half of asymptomatic subjects and 30% have a posterior disc protrusion.10 A recent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) study found a prevalence of thoracic disc herniations of 37% in asymptomatic subjects, disc bulging in 53% and annular tears in 58%.11 Another study of asymptomatic patients identified impressive disc protrusions in no less than 16%.12 An unexpectedly high prevalence of thoracic disc herniation (14.5%) was also demonstrated in the thoracic spines of a group of 48 oncology patients examined by MRI.13 Although these relatively high figures do not correspond to the real clinical situation, we believe that symptomatic thoracic disc protrusions are far more common than is generally accepted and agree with Krämer,14 who estimated the frequency of thoracic disc lesions to be about 2% of all symptomatic disc lesions. Recent studies also confirmed the incidence of symptomatic thoracic disc prolapses as being between 0.15% and 4% of all intervertebral disc prolapses.15,16 Although more frequently present than commonly believed, thoracic disc protrusions are clinically far less common than those in the lumbar spine because of the greater rigidity of the thoracic spine. This is partly a result of the stabilizing effect of the rib cage on the thoracic spine and partly due to the thoracic intervertebral discs, which are thinner on account of a less voluminous nucleus pulposus.17 Therefore extension and flexion movements are of a smaller range in the thoracic spine. Minor thoracic disc lesions occur most often between T4 and T8. Those with cord compression are usually found in the lower half of the thorax.6,18 About 70% lie between T9 and T12, the commonest level (29%) being T11. A logical explanation for this could be that the lower segments have an increased mobility due to free ribs at these levels.19 Another reason could be that the cord has a critical vascular supply at this level.20 It is hypothesized that disc degenerations and disc displacements are of themselves painless events because the disc is almost completely without nociceptive structures. Clinical syndromes originate only when a subluxated fragment of disc tissue impinges on the sensitive dura mater or on the dural nerve root sleeve. This clinical hypothesis is extensively discussed in the lumbar section of this book (see Chs 31 and 33). Posterocentral protrusions compressing the dura mater may provoke multisegmental pain, which is mainly referred into the posterior thorax but may also spread into the anterior chest, the abdomen or the lumbar area.21 The pain is never referred down the arm. When a posterocentral displacement increases, cord compression can result. When the T1 nerve root is compressed by a disc lesion, pain is referred to the inner side of the arm between elbow and wrist. A T2 nerve root impingement creates pain referred towards the clavicle and to the scapular spine and down the inner side of the upper arm. The corresponding dermatomes of the T3–T8 nerve roots follow the intercostal spaces, ending at the lower margin of the thoracic cage. The dermatomes of T9–T11 include a part of the abdomen, and T11 also includes part of the groin (see Fig. 25.3).22,23 Thoracic disc protrusions may give rise to four different clinical presentations: chronic thoracic backache, acute thoracic lumbago, thoracic root pain and spinal cord compression (Cyriax:24 pp. 202–205). The clinical findings in symptomatic thoracic disc displacements are analogous to the lumbar and cervical disc syndromes. Again, both dural and articular signs and symptoms can be identified (see Ch. 52). Examples of non-articular patterns are illustrated in Figure 27.1. Often both articular and dural signs are present, although the latter are sometimes absent. Pain and limitation on side flexion towards the painless side as the only positive movement does not match the pattern of a disc lesion. Other disorders, such as a pulmonary or abdominal tumour with invasion of the thoracoabdominal wall, must be considered. An intraspinal tumour – for example, a neurofibroma – is also possible (see online chapter Disorders of the thoracic spine and their treatment). In thoracic disc lesions, careful attention must always be paid to abnormal neurological elements that may indicate compression of the spinal cord: pins and needles in both feet, disturbed coordination of lower limbs and positive Babinski’s sign (see Table 27.1 and pp. 165–168). Table 27.1 Articular and dural symptoms and signs in thoracic disc lesions Symptomatic disc displacements in the thoracic spine may give rise to four different clinical syndromes: acute thoracic ‘lumbago’, chronic thoracic backache or ‘dorsalgia’, thoracic root pain and spinal cord compression (Figs 27.3–27.5).24 Each syndrome corresponds to a specific type of disc lesion. In this condition the disc gradually dehydrates as the result of the prolonged sitting position.25 Simultaneously, the imposed kyphosis pushes the whole intra-articular content of the disc posteriorly, compressing the dura mater and resulting in thoracic backache. On lying down, the effects of hyperkyphosis and gravity are largely diminished and the disc shifts spontaneously back into its original position. These patients should avoid prolonged anteflexion. Manipulative reduction is useless but sclerosant infiltrations may be helpful. Recurrence may occur but the pain is not necessarily always felt at the same side. • In a primary posterolateral protrusion, segmental pain is felt from the start at the lateral aspect of the thorax and often radiates unilaterally to the front of the chest or the abdomen. The absence of pain in the back may lead to the discogenic origin being overlooked. • In a secondary posterolateral protrusion, an extrasegmental posterocentral or posterior unilateral pain is initially present, which then moves more to the side and sometimes towards the anterior thorax or abdomen – meanwhile becoming segmentally referred – a sequence of symptoms that strongly suggests a secondary posterolateral disc lesion. Both types of root compression give rise to segmental referred pain. This has a unilateral band-shaped distribution that follows the intercostal nerves. At the thoracic level a posterolateral protrusion seldom gives rise to pins and needles. If present, they follow the same segmental distribution as the pain. As the T12 dermatome spreads into the lower abdomen, interference with this nerve root can result in pain and occasionally pins and needles in the groin and/or the testicles.26 A T1 root palsy is detected during the clinical examination of the cervical spine. It is seldom the result of a disc protrusion but usually the outcome of a serious disorder such as a superior sulcus tumour of the lung, a neurofibroma or vertebral metastases. Although T1–T2 discoradicular compressions with neurological deficit have been reported,27–29 it should be kept in mind that if a neurological deficit of T1 is present, more severe disorders should always be excluded first (see see online chapter Disorders of the thoracic spine and their treatment). Thoracic disc lesions compressing a nerve root do not usually resolve spontaneously, although there are a few reports of spontaneous regression at a lower thoracic level.30,31 However, posterolateral thoracic disc protrusions which cause root pain remain reducible by manipulation, no matter how long they have existed. Where manipulation has failed or where neurological deficit is present, a sinuvertebral block should be given. The spinal cord is most vulnerable at the lower thoracic levels, between T9 and T12,29,32 because the spinal canal is at its narrowest there and the vascularization is at its most critical.33 It has been suggested that signs of cord compression do not always stem from pressure on the cord itself, but rather are the result of interference with the blood supply.3–5 Osteophytes narrowing the spinal canal are an extra contributing factor.34 Previous injury to the thoracic spine can also play a role in the later development of cord compression, although this circumstance is rare. Initially almost all patients complain of pain. It is never particularly severe, often has a vague band-shaped distribution, and may sometimes disappear completely.35–38 It is usually localized in the back, although it may radiate into the pelvis or groin and down the legs. Occasionally, patients complain of subumbilical pain.1 The quality varies from a constant, dull and burning pain to – exceptionally – a lancinating, cramping and spasmodic pain. Later in the course, unilateral or bilateral numbness may set in and may be accompanied by a motor palsy. The numbness is more a diminution of normal sensation than a complete loss of sensitivity. It often starts at the big toe and is accompanied by a subjective sensation of coldness.3 Some or all of the following neurological signs may be present: • Disturbed coordination with spastic gait. • Increased muscle tone, with the affected muscles not limited to one myotome.39 Occasionally, weakness of the lower abdominal muscles can be demonstrated, when the umbilicus is seen to move as the patient attempts to sit up.1 This is known as Beevor’s sign. • Weakness and/or atrophy of some lower limb muscles. • Hyperreactive patellar or Achilles tendon reflexes with ankle clonus. • Occasionally, absent tendon reflexes, particularly and inevitably when a flaccid type of paraplegia is present. The abdominal reflexes are often absent or diminished, most commonly in both lower quadrants. All these signs may be unilateral or bilateral. • Positive Babinski’s and Oppenheim’s signs. • Absence of the cremasteric reflex. • Limitation of straight leg raising, sometimes bilateral.2 • Occasionally, a Brown–Séquard syndrome in cord compression.6

Disorders of the thoracic spine

Disc lesions

Introduction

Clinical presentation

Symptoms and signs

Articular signs

Symptoms and signs of cord compression

Symptoms

Signs

Articular

Particular movements or postures increase the pain; others ease

Existence of a partial articular pattern

Dural

Pain on deep breath

Pain on neck flexion

Pain on scapular movements

Clinical types of thoracic disc protrusion

Thoracic backache

Special case: self-reducing disc lesion

Acute thoracic lumbago

Thoracic root pain

Compression of the spinal cord

History

Pain

Numbness

Functional examination

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree