Chapter 15 Disorders of the Subtalar Joint, Including Subtalar Sprains and Tarsal Coalitions

Anatomy

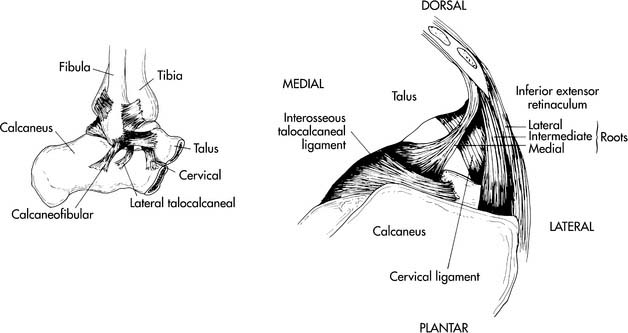

The subtalar joint is comprised of three articulating surfaces, referred to as the posterior facet, the middle facet, and the anterior facet. The bony articulations provide inherent stability and soft tissues provide additional stabilization. The lateral soft-tissue stabilizers have been classified into three separate layers.1 The superficial layer is composed of the lateral root of the inferior extensor retinaculum, the lateral talocalcaneal ligament, and the calcaneofibular ligament. The intermediate layer consists of the intermediate root of the inferior extensor retinaculum and the cervical ligament. The deep layer consists of the medial root of the inferior extensor retinaculum and the interosseous talocalcaneal ligament (Fig. 15-1).

Figure 15-1 The anatomy of the subtalar joint.

From Mann RA, Coughlin MJ, editors: Surgery of the foot and ankle, ed 7, St Louis, 1999, CV Mosby, p 1147, Figure 26-57.

Subtalar Instability

The role that instability of the subtalar joint plays in the patient with lateral ankle instability has been elucidated only recently. It has been estimated that 10% to 30% of patients with functional ankle instability, that is, patients that have pain, swelling, or a sense of “giving way” of the ankle, have evidence of instability of the subtalar joint.2,3 Some have suggested that consideration should be given to the concept of global hindfoot instability rather than simply functional instability about the ankle joint.4

Instability of the subtalar joint was first described in 1962 by Rubin and Whitten.5 They proposed a series of stress radiographs to further evaluate this disorder. Brantigan et al.6 were the first to detect radiographic evidence of subtalar instability in their series of three patients. Chrisman and Snook7 in 1969 were able to document clinical subtalar instability in three of seven patients who were undergoing their tendon transfer procedure for lateral instability. Clanton and Berson8 described subtalar injuries as a continuum of other injuries in athletes, particularly sprains of the lateral ankle ligaments.

Clinical presentation

The typical injury that leads to instability of the subtalar joint is a severe supination or supination-inversion force applied to the hindfoot. This results in a progressive injury to the talonavicular ligament and talonavicular capsule, followed by injury to the calcaneofibular and lateral talocalcaneal ligaments.8 The presenting complaint often is a sensation of giving way of the ankle. The patient may report pain localized to the region of the sinus tarsi. Athletic activities can exacerbate the symptoms, resulting in a dependence on bracing or taping. Uneven surfaces may cause pain and a feeling of instability.

Physical examination

The most notable finding on physical examination is increased inversion of the subtalar joint. This should be compared with the presumably uninjured opposite limb. The increased inversion can result from subtalar instability or a combination of subtalar and ankle instability.4,8 It is extremely difficult to detect the location of increased inversion by examination. In addition to increased inversion of the hindfoot, an increased translation of the calcaneus in the medial direction has been noted by Thermann et al.9 In their study, a valgus stress was applied to the calcaneus, followed by an abrupt internal rotation stress. Results showed a medial shift of the calcaneus in relation to the talus or an opening of the talocalcaneal angle in patients with subtalar instability.

Radiographic evaluation

Plain radiographs often are negative, and further investigation must be carried out to arrive at the diagnosis. There have been multiple investigations into the use of stress radiographs in the workup of subtalar instability (Fig. 15-2).6,10–12 In a series of three patients, Brantigan et al.6 were able to radiographically demonstrate subtalar instability. They attributed the instability to an injured calcaneofibular ligament. Heilman et al.12 sequentially sectioned ligaments in cadaver limbs and then obtained lateral and Broden’s radiographs. They found that sectioning of the calcaneofibular joint caused a 5-mm opening of the subtalar joint. With subsequent sectioning of the interosseous ligament, the joint opened up to 7 mm.

The usefulness of stress radiographs has come into question by multiple authors.13–15 Harper13 reported a wide range of subtalar tilt with stress radiographs in his group of asymptomatic patients. Louwerens et al.14 examined 33 patients with chronic ankle instability and 10 control patients who were asymptomatic. Broden’s views were checked under fluoroscopy and they detected no difference between symptomatic and asymptomatic feet with regard to subtalar tilt or medial shift. Van Hellemondt et al.15 examined both stress radiographs and stress computed tomography (CT) scans in 15 patients with unilateral chronic ankle instability with suspected subtalar instability. Although three of the symptomatic feet and one of the asymptomatic feet had increased subtalar tilt on plain films, there was no significant difference between the symptomatic and asymptomatic sides. None of the patients had increased subtalar tilt on the stress CT scans. The authors therefore doubted that a Broden’s stress examination reveals the true amount of subtalar tilt.

Nonoperative treatment

In an acute injury, the usual treatment regimen for lateral ankle sprains will suffice for subtalar ligamentous injuries, as well. Rest, ice, compression, and elevation (RICE) are part of a good protocol, as well as immobilization and physical therapy, when needed. The same can be said for management of chronic subtalar instability. The routine nonoperative regimen used for chronic lateral ankle instability is initiated. This may include proprioceptive training, peroneal strengthening, and bracing or strapping.8,16 With bracing, it is important to understand the delicate balance in providing an athlete with enough support without impeding his or her performance. Taping by an athletic trainer before participation can be effective. Wilkerson17 examined a modification of the standard method of ankle taping with the incorporation of a “subtalar sling.” He found that addition of the sling enhances the protective function of taping but cautioned that it may impede performance of certain activities.

Surgical treatment

Patients with residual symptomatic instability despite an adequate program of nonoperative management will require a surgical stabilization of their subtalar joint. If both ankle and subtalar instability exist and require surgery, both problems should be corrected at the time of surgery.4 Surgical stabilization involves direct ligament repair or tendon transfers to substitute for the irreparable ligaments.

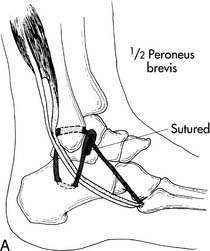

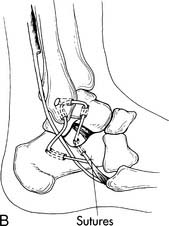

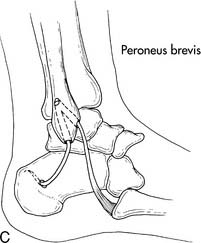

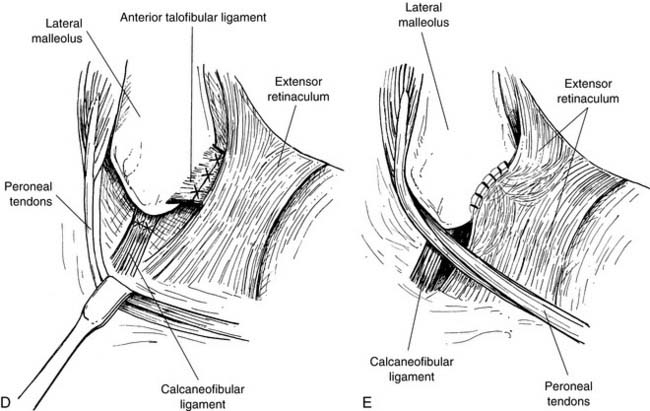

Surgical techniques resulting in ankle and subtalar stability concurrently are numerous (Fig. 15-3, A through C).2,7,9,18–26 Most techniques require some form of extraarticular tendon transfer to provide stability. Kato25 and Pisani26 described techniques involving intraarticular ligament reconstruction of the interosseus ligament between the calcaneus and talus.

A less invasive technique that, according to Clanton and Berson8 and Gould et al.,22 provides a good treatment for subtalar instability is the Brostrom-Gould reconstruction technique for lateral ankle instability (Fig. 15-3, D and E). With the reconstruction of the calcaneofibular ligament (CFL) and anterior talofibular ligament (ATFL) buttressed by the inferior extensor retinaculum, subtalar stability is effectively restored.8,22

Sinus Tarsi Syndrome

Symptoms of sinus tarsi syndrome may overlap with those associated with subtalar instability. Some authors consider this syndrome simply a variant of subtalar instability.27 Sinus tarsi syndrome describes pain localized to the region of the sinus tarsi. Characteristic findings on clinical and radiographic examination have not been well defined. Likewise, the pathologic changes found at the time of surgery are unclear. The most widely reported description of the pathologic anatomy associated with this condition is degenerative changes to the soft tissues of the sinus tarsi.28,29 The majority of cases are posttraumatic in nature but also may be related to inflammatory arthropathies, gout, ganglion cysts, and structural foot abnormalities.30,31

Clinical presentation

The typical complaint is pain over the lateral and anterolateral ankle and hindfoot centered in the region of the sinus tarsi. The patient may report a sensation of mild hindfoot instability. It has been estimated that as many as 70% of patients with sinus tarsi syndrome have had a previous inversion injury to the hindfoot.32

Radiographic evaluation

Plain films often are negative in this condition. Stress views may reveal mild subtalar instability, but, as stated in the previous section, these are of uncertain value. Subtalar arthrograms have been used in the workup of this condition. The normal subtalar joint will accept 3 ml of contrast dye and will demonstrate multiple recesses and interdigitations within the joint capsule.18 Under normal circumstances there is a small recess that projects anteriorly from the subtalar joint. The absence of this synovial recess has been associated with sinus tarsi syndrome.30,32

The use of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in the evaluation of sinus tarsi syndrome has been investigated. The key MRI features have been reported as replacement of the normal fat signal intensity in the sinus tarsi with fluid, inflammatory tissues, or fibrosis.31,32 The inflammatory changes often will obscure the ligaments that normally are visualized in the sinus tarsi. Additional findings may include ligament injury, ganglion cysts, and degenerative joint disease.33

Nonoperative treatment

Injections of local anesthetic and steroid into the sinus tarsi may be both diagnostic and therapeutic. If the patient does not report even temporary relief following injection, then skepticism must be directed at a diagnosis of sinus tarsi syndrome. Some patients may report permanent resolution of their symptoms after a series of injections.18 Surgery is indicated if pain recurs after a series of one to three injections.

Surgical treatment

Open and arthroscopic techniques are available. Open excision of the tissue filling the sinus tarsi has been reported to have good results.18,29,30 Typically a lateral oblique incision is made over the region of the sinus tarsi. The lateral branch of the superficial peroneal nerve is avoided. The inferior extensor retinaculum and the origin of the extensor digitorum brevis are reflected distally. The sinus tarsi is entered, and debridement is performed. Arthroscopic exploration (Fig. 15-4) of the sinus tarsi for diagnosis and treatment has been described with good results, but often the postoperative diagnosis is changed from sinus tarsi syndrome to another more anatomic pathology, following direct visualization of the sinus tarsi area and the subtalar joint.27

Subtalar Dislocation

A subtalar dislocation involves the dislocation of the talocalcaneal and talonavicular joints. With this injury there is no associated dislocation of the calcaneocuboid or tibiotalar joints. It was first described separately by DuFaurest34 and Judcy35 in 1811. Broca36 later classified these injuries as medial, lateral, and posterior. In 1856, Malgaigne37 revised this classification and added anterior subtalar dislocations as a specific entity. Frequency of the different subtypes of subtalar dislocations has been reported as 80% medial, 17% lateral, 2% posterior, and 1% anterior.38

Clinical presentation

These injuries typically are the result of high-energy mechanisms such as motor vehicle accidents or falls from a height. They also can result from a twisting athletic injury. In 1964, Grantham39 used the term “basketball foot” to describe medial dislocations because four of the five patients in his series injured their foot playing basketball. Low- and high-energy mechanisms create two subtypes of subtalar dislocations. High-energy injuries are more likely to be open, more likely to be lateral, have a higher incidence of associated fracture, and have a worse long-term prognosis.40

Significant foot deformity is found in all patients with subtalar dislocation, although this may be somewhat obscured by swelling. Approximately 20% to 40% of subtalar dislocations are open.41–43 However, open injuries are unusual in the athlete.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Pearl

Pearl