• Relaxation training with or without thermal biofeedback, electromyographic (EMG) biofeedback, and cognitive-behavioral therapy may be considered in preventing migraine (Grade A). No recommendations could be made about which modality is best suited to specific patients.

• Relaxation therapy and biofeedback may be combined with prophylactic medications to achieve additional clinical improvement (Grade B).

• No recommendations could be made concerning hypnosis, acupuncture, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation, cervical manipulation, occlusal adjustment, or hyperbaric oxygen (Grade C).8

Medications

Migraine Prophylaxis

Preventive therapy aims to reduce migraine-associated disability by reducing the number, severity, and duration of migraine attacks. Prophylactic therapy requires adherence but should be considered when the patient perceives that the benefits of prophylaxis outweigh the disadvantages (e.g., adherence to daily medication, potential adverse effects, cost). By some estimates, nearly 40% of migraine patients could benefit from prophylactic therapy, but less than 13% currently use it.9 Indications for prophylactic therapy include:

• Frequent, severe, prolonged, and disabling migraine attacks

• Poor response and/or adverse effects limiting use of acute migraine therapy

• Desire to reduce costs of acute therapy

• Rare migraine subtypes associated with potential neurologic damage (e.g., hemiplegic, basilar, prolonged aura)

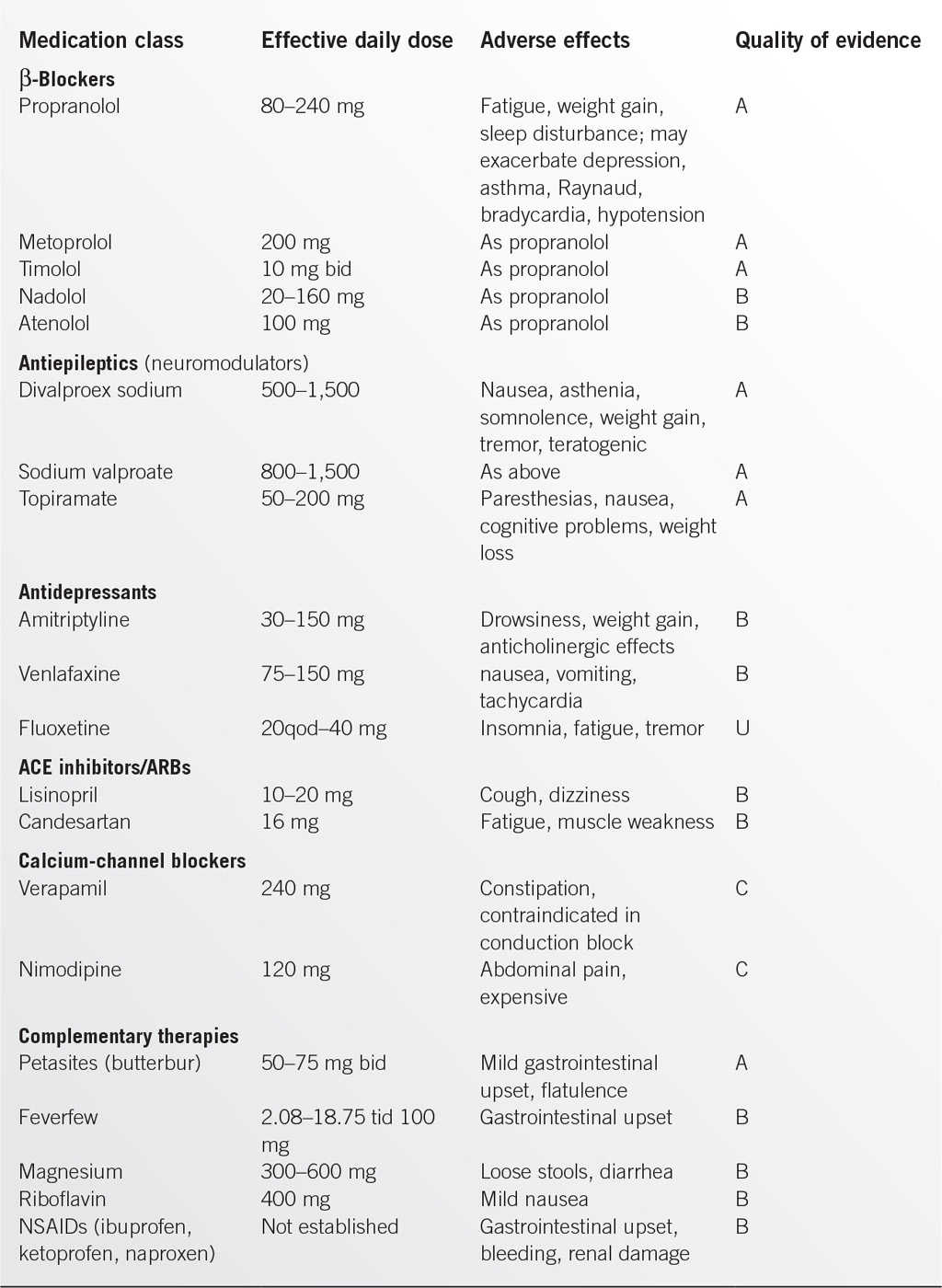

In addition to cost and ease of use, choice of a prophylactic medication depends on efficacy plus the potential for “added benefit” for an individual patient (e.g., antihypertensive or antidepressive effect) or adverse effect such as vasoconstriction or sedation. The selected medication should be started at a low dose and increased slowly until an effective dose is established. This requires several months of monitoring for effectiveness, adherence, and potential adverse effects.

The most recent guidelines (2012)10 made the following recommendations for migraine prevention on the basis of the evidence of efficacy:

• Effective and should be offered to suitable patients (level A)

• β-Blockers: propranolol, metoprolol, timolol

• Antiepileptic drugs: divalproex sodium, sodium valproate, topiramate

• Triptans: frovatriptan (short term for menstrually-associated migraine)

• Probably effective and should be considered in suitable patients (level B)

• β-Blockers: atenolol, nadolol

• Antidepressants: amitriptyline, venlafaxine

• Triptans: naratriptan, zolmitriptan (short term for menstrually-associated migraine)

• Possibly effective and may be considered in suitable patient (level C)

• β-Blockers: nebivolol, pindolol

• Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors: lisinopril

• Angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs): candesartan

• α-Agonists: clonidine, guanfacine

• Antiepileptic drugs: carbamazepine

• Evidence is inadequate or conflicting: cannot support or refute use for migraine prevention (level U)

• β-Blockers: bisoprolol

• Antiepileptic drugs: gabapentin

• Antidepressants: fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, protriptyline

• Calcium-channel blockers: nicardipine, nifedipine, nimodipine, verapamil

• Acetazolamide

• Cyclandelate

More recently, guidelines have been published concerning the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and complementary treatments in migraine prevention.11

From the many herbs and other substances studied, evidence of reduction in frequency and severity of attacks (level A recommendation) was found only for petasites (extract of butterbur) in doses 50 to 75 mg bid. Limited evidence (level B recommendation) was found for riboflavin (400 mg), feverfew (100 mg), and magnesium (300 mg). Level B recommendations were made for naproxen sodium, fenoprofen, ibuprofen, and ketopofen, but the benefits were perceived to be modest and based on limited data. Level C recommendations were made for flurbipofen and mefenamic acid. Aspirin and indomethacin received level U recommendations.11

Treatment of the Acute Attack

Goals for the management of migraine attacks include:

• Rapid and consistent relief of symptoms

• Prompt return to normal functioning

• Minimal risk of recurrence of symptoms

• Limited or acceptable adverse effects

• Minimal use of backup medications

• Cost effectiveness for patient and health systems

Individualizing therapy is essential to optimize relief of symptoms and enhance adherence with therapy. Patients and their significant others should be educated about migraine and encouraged to take responsibility for self-management. Factors in selecting therapy include:

• Targeting the most troublesome symptoms (e.g., pain, vomiting, exhaustion)

• Synchronizing medication efficacy with migraine pattern (e.g., speed of onset, time to peak symptoms, duration of symptoms, tendency to recur, time between attacks)

• Considering comorbidities and factors that limit medication choices (e.g., gastric bleeding, some forms of heart disease, potential for pregnancy, use of other medications)

• Optimizing patient confidence in medication and preference for route of administration

• Considering cost and availability of medication (including limits on number of doses per month)

The current US Headache Consortium guidelines4,12 are due to be revised soon, but the key recommendations concur with 2009 European guidelines that incorporated more recent evidence.13 From the many treatments studied, the US Headache Consortium found pronounced statistical and clinical benefit for some analgesics, ergotamines, and triptans.4,12

Analgesics and Symptomatic Medications

Analgesics such as aspirin, ibuprofen, and naproxen can effectively control migraine symptoms (especially early in the attack) if absorbed in adequate doses. Several antiemetics have some direct antimigraine effect in addition to addressing nausea and vomiting and are recommended to be given before NSAIDs or triptans in the European guidelines. In appropriate doses, the combination of aspirin and metoclopramide is as effective as sumatriptan.14 Caffeine also has a weak antimigraine effect and appears to enhance other medications. The optimal analgesic agent (or combination of analgesics and other symptomatic agents) and dose has to be developed for each patient, but all should be counseled to treat early in the attack, control the dose and frequency of dosing to avoid rebound headache, and to report any adverse effects. Simple analgesics should not be taken for more than 15 days per month (10 days for combinations) to minimize the risk of transforming migraine into chronic daily headache from drug overuse. Both the US and European guidelines found no role but significant potential dangers in the use of butalbital for migraine. The relatively minor efficacy of opiates is more than that countered by adverse effects, principally nausea and somnolence, and the significant risk of abuse.

Ergotamines

These traditional migraine therapies are available for oral, injectable, nasal, or rectal use. The best evidence of efficacy is for dihydroergotamine (DHE) given nasally, intramuscularly, intravenously, or subcutaneously. The action is enhanced by combination with an antiemetic. The main adverse effects relate to vasoconstriction, nausea, and rebound headache. These medications must not be used during pregnancy or when vasoconstriction is contraindicated (e.g., peripheral vascular disease, coronary artery disease). Ergotamine use must be limited to under 10 days per month owing to the risk of inducing drug overdose headache.

Triptans (Serotonin 5-HT1B/1D Agonists)

The currently available triptans differ mainly in bioavailability, speed of effect, and duration of action. Clinical efficacy appears similar within the group, but a patient may respond well to one agent but not another. The choice of initial agent should be based on matching the pharmacologic properties of the drug (such as speed or duration of action) to the migraine pattern of an individual patient. The form of administration can also be adapted to patient needs as some triptans are available in nasal- or oral-dissolving forms and sumatriptan can be given subcutaneously. Triptans are contraindicated in basilar and hemiplegic migraine and in patients with heart disease or uncontrolled hypertension. Nausea, flushing, and palpitations may occur. About 15% to 40% of patients experience recurrence within 24 hours of taking an oral triptan. This can be reduced by giving triptans early in the attack (but not during the aura) and/or adding an NSAID (such as naproxen). A second dose of triptan is often effective for migraine recurrence. Triptan use should be restricted to up to 9 days per month to avoid development of chronic headache. Triptans are significantly more expensive than most alternative treatments.

Surgery and Procedural Interventions

Small studies report improvement in the frequency and intensity of migraine following injection of trigger areas with botulinum toxin. This treatment is advocated for patients with migraine triggered by muscle tension, those with concurrent tension headaches, and patients with migraine on 15 or more days per month in whom other treatments have been unsuccessful. One case series reported significant improvement at 5 years in 88% of 69 patients. Studies of patients treated for paradoxical cerebral embolism identified a high prevalence of migraine (especially with aura) that resolved or improved significantly after closure of patent foramen ovale.

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS

Migraine is a long-term condition that patients should be encouraged to manage with advice and support from their physicians. Depression and other stress-related conditions have traditionally had a high prevalence in patients with migraine. With positive coaching by physicians and individualized management utilizing the range of effective therapies, the impact of migraine on quality of life should be minimized.

REFERENCES

1. Headache Classification Subcommittee of the International Headache Society. The international classification of headache disorders: 2nd edition. Cephalalgia 2004;24:9–160.

2. Stewart WF, Wood C, Reed ML, et al; AMPP Advisory Group. Cumulative lifetime migraine incidence in women and men. Cephalalgia 2008;28:1170–1178.

3. Victor TW, Hu X, Campbell JC, et al. Migraine prevalence by age and sex in the United States: a lifespan study. Cephalalgia 2010;30:1065–1072.

4. Silberstein SD. Practice parameter: evidence-based guidelines for migraine headache (an evidence-based review). Neurology 2000;55:745–762.

5. Detsky ME, McDonald DR, Baerlocher MO, et al. Does this patient with headache have a migraine or need neuroimaging? JAMA 2006;296:1274–1283.

6. Frishberg BM, Rosenberg JH, Matchar DB et al. Evidence-based guidelines in the primary care setting: neuroimaging in patients with nonacute headache. US Headache Consortium 2000. http://tools.aan.com/professionals/practice/pdfs/gl0088.pdf.

7. Diamond M, Cady R. Initiating and optimizing acute therapy for migraine: the role of patient-centered stratified care. Am J Med 2005;118:18S–27S.

8. Campbell JK, Penzien DB, Wall EM. Evidence-based guidelines for migraine headache: behavioral and physical treatments. US Headache Consortium. http://tools.aan.com/professionals/practice/pdfs/gl0089.pdf.

9. Lipton RB, Bigal ME, Diamond M, et al.; The American Prevalence and Prevention Advisory Group. Migraine prevalence, disease burden, and the need for preventive therapy. Neurology 2007;68:343–349.

10. Silberstein SD, Holland S, Freitag F, et al. Evidence-based guideline update: pharmacologic treatment for episodic migraine prevention in adults. Neurology 2012;78:1337–1345. http://www.neurology.org/content/78/17/1337.full.pdf+html.

11. Holland S, Silberstein SD, Freitag F, et al. Evidence-based guideline update: NSAIDs and other complementary treatments for episodic migraine prevention in adults. Neurology 2012;78:1346–1353.

12. Matchar DB, Young WB, Rosenberg JH, et al. Evidence-based guidelines for migraine headache in the primary care setting: pharmacological management of acute attacks. US Headache Consortium. http://tools.aan.com/professionals/practice/pdfs/gl0087.pdf. Accessed November 2013.

13. Evers S, Afra J, Frese A, et al. EFNS guideline on the drug treatment of migraine—revised report of an EFNS task force. Euro J Neurol 2009;16:968–981.

14. Tfelt-Hansen P. The effectiveness of combined oral lysine acetylsalicylate and metoclopramide in the treatment of migraine attacks. Comparison with placebo and oral sumatriptan. Funct Neurol 2000;15:196–201.

15. Guyuron B, Kriegler JS, Davis J, et al. Five-year outcome of surgical treatment of migraine headaches. Plast Reconstr Surg 2011;127:603–608.

16. Wahl A, Praz F, Tai T, et al. Improvement of migraine headaches after percutaneous closure of patent foramen ovale for secondary prevention of paradoxical embolism. Heart 2010;96:967–973.

|

GENERAL APPROACH TO THE PATIENT WITH HEADACHE

Headaches were ranked in the top three most prevalent disorders and as top ten causes of disability in the Global Burden of Disease Survey 2010. The third edition of the International Classification of Headache Disorders (ICHD-3) divides headaches into three main forms: primary headaches, secondary headaches, and other headaches. This chapter intends to review the non-migrainous primary headaches. However, differentiating primary headache syndromes such as migraine, cluster, and tension headaches from the potentially serious forms of secondary headaches caused by tumor, vascular disease, or infection is a critical task. The current recommendation is to attempt headache classification based on the patient’s headache phenotype within the last year.

History

It is important to inquire about the patients’ historical change of headache symptoms. This would include how many types of headaches the patient has, current age, and age of onset of different headaches. The frequency, duration, rapidity of onset, intensity, location, and character of pain are all important. One should ascertain the presence of provoking and palliating factors, including medicines (and frequency of use) that have or have not been effective. Review of associated symptoms includes nausea, vomiting, typical aura, focal neurologic and localized autonomic symptoms (such as lacrimation and rhinorrhea), and neck pain or stiffness. Red flags for secondary etiologies include presence of fever, history of any type of trauma, history of systemic infections (HIV, sepsis), changes in mental status, history of cancer, and newly diagnosed diseases as well as new drugs. New focal symptoms, pattern change, or progression in a previously stable pattern of headaches is a concern, as is onset before age 5 or after age 50. In acute settings, it is important to ask the patient if the current episode is their worst headache ever. It is rare for the patients to volunteer this critical piece of information, and its presence must prompt imaging and spinal tap considerations.

Examination

Headache with fever or neck stiffness requires exclusion of central nervous system (CNS) infection. Complete neurological exam is necessary, including strength, gait, reflexes, and Babinski sign check. Fundoscopic examination should be done on every patient to rule out papilledema and the presence or absence of spontaneous venous pulsations (reassuring if present, not pathologic if absent).

Laboratory and Imaging Studies

Most patients with typical migraine, tension headache, or other well-defined primary headache syndromes do not need further testing. Sedimentation rate, anti-nuclear antibody (ANA), and C-reactive protein should be checked in adults with new headaches. Temporal artery biopsy should be considered if concerned for temporal arteritis. Sleep study can be considered to exclude obstructive sleep apnea if headaches are worse in the morning. Since headaches are prominent in carbon monoxide poisoning, carbomethoxyhemoglobin testing could be ordered if suspected.

Neuroimaging

• Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI, preferable to head computerized tomography [CT] when possible) should be done in patients with atypical history, red flags, abnormal cognitive or neurological exam, acute hypertensive crisis, progressive symptoms, and history of cancer or trauma. New headaches associated with cough, sex, or exertion should be evaluated by imaging to exclude structural abnormalities. If brain MRI is negative, and symptoms are suggestive for cerebral venous thrombosis (CVT), MRI- or CT-venogram should be considered. Acute unilateral headaches with any focal symptom should also prompt use of magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) imaging of the neck to rule out arterial dissection. Patients with high risk of aneurysmal disease need MRA of the head also.

• Imaging the sinuses (usually with CT) can find occult sinusitis, especially of the sphenoid sinuses.

• “Worst-ever” headaches should be emergently evaluated with neuroimaging (usually CT). If CT scanning herniation does not appear to be a risk, then lumbar puncture should be performed to rule out subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH, looking for xanthochromia).

Lumbar Puncture

Always check opening pressure to look for elevated intracranial pressures (can be seen in hydrocephalus, infections, pseudotumor cerebri, etc.).

• Lympho- or carcinomatous meningitis requires serial spinal taps with cytology and flow cytometry before they can be ruled out.

• HIV and other immunocompromised patients should be aggressively evaluated for possible CNS opportunistic infections.

• Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) Lyme disease tests can occasionally be positive in the absence of positive peripheral titers. Urgent examination by an ophthalmologist is indicated if angle closure glaucoma or iritis/uveitis is suspected on the basis of a red painful eye.

CLUSTER AND OTHER TRIGEMINAL AUTONOMIC CEPHALALGIAS

Definition/Diagnosis

• Trigeminal autonomic cephalalgias (TACs) are severe unilateral headaches with ipsilateral parasympathetic features. They are differentiated by their frequency, duration, and responsiveness to certain medications.

• Cluster headaches consist of attacks of severe, unilateral head or face pain, lasting 15 to 180 minutes, with a frequency of 1 to 8 times per day. Attacks are associated with ipsilateral autonomic symptoms, including conjunctival injection, lacrimation, nasal congestion, rhinorrhea, eyelid edema, facial and/or forehead swelling, miosis, ptosis, with or without restlessness and agitation. Pain is excruciating, and patients are usually pacing and restless as opposed to patients with migraine. Being more common in young males, attacks occur in spells, often nocturnal, often at the same time each day on the same side of the head. Episodic cluster headaches occur in periods lasting 7 days to 1 year, separated by pain-free periods of at least 1 month. Recurrent attacks may switch sides, but side remains the same within a cluster. About 10% to 15% of patients have chronic cluster headaches, where symptoms occur for more than 1 year without remission or with remissions lasting less than 1 month.

• Paroxysmal hemicrania is characterized by similar attacks but lasting 2 to 30 minutes with a frequency of many times per day, and an exquisite response to indomethacin (150 to 225 mg daily).

• Hemicrania continua is a persistent (>3 months) unilateral headache with ipsilateral autonomic symptoms, absolutely sensitive to indomethacin.

• Short-lasting unilateral neuralgiform headache attacks include SUNCT (with prominent ipsilateral conjunctival redness and tearing) and SUNA (without one or neither eye symptoms).

Pathophysiology/Epidemiology

Activation of the posterior hypothalamic gray matter, vasodilation, and activation of the trigeminal parasympathetic reflexes are believed to be the underlying phenomena in TACs. Approximately 5% of cluster headaches are inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern. Cluster and the other TAC headaches are all relatively rare affecting 1% of the population or less.

Workup

Detailed headache and neurologic history, family history, and complete neurologic exam are indicated. CT/MRI/MRA imaging or carotid ultrasound may be indicated if there are findings other than the usual associated trigeminal autonomic symptoms described above or if carotid artery dissection is suspected. Eye pressure measurement is needed to rule out intermittent glaucoma.

Differential Diagnosis

Once neurological emergencies have been ruled out (SAH, CVT, carotid dissection, angle closure glaucoma, uveitis, etc.), the primary differential process is to determine the type of TAC. The importance of the differentiation between cluster and noncluster TACs is highlighted by the exquisite sensitivity to indomethacin. Trigeminal neuralgia may mimic SUNCT but lacks the associated autonomic findings.

Treatment

• Acute treatments for cluster headache that have shown efficacy include triptans (most often given by injection), inhaled oxygen, and the somatostatin analog octreotide. Most patients with cluster headache require prophylactic therapy.

Cluster and Trigeminal Autonomic Cephalalgias Pharmacotherapy |

Agent | Headache type/Rx class |

Abortive treatments |

|

Sumatriptan injection (Imitrex)a | Cluster: Triptan |

Sumatriptan (Imitrex), Zolmitriptan (Zomig) nasal | 5HT (1B/1D) agonist |

Sumatriptan (Imitrex), Zolmitriptan (Zomig), others oral | SUNCT headachesb |

Oxygen by inhalation, high flow ~7–15 L/min | Cluster: molecular agent—mechanism of action unknown |

Ergotamine and dihydroergotamine by various parenteral routes of administration (oral not generally effective for abortive treatment, but may be used as transitional agents to chronic prophylactic treatments) | Cluster: vasoconstrictor, 5HT (1B/1D) agonist and suppresses neurogenic inflammation |

Octreotide injectable (expensive, considered investigational) | Cluster: somatostatin analog |

Indomethacin (Indocin) | Paroxysmal hemicrania: Response to this agent is uniform and diagnostic |

Preventive treatments |

|

Verapamil | Cluster: calcium-channel blocker |

Prednisone/other steroids | Cluster: corticosteroid |

Lithium | Cluster: ionic agent, class indeterminate |

Methysergide (ergot derivative)—off U.S. market due to toxicity concerns | Cluster: ergot derivative |

Valproic acid (Depakote) | Cluster: anticonvulsant |

Topiramate (Topamax) | Cluster: anticonvulsant |

Indomethacin (Indocin) | Paroxysmal hemicrania: highly effective |

| Cluster: possibly some degree of responsiveness |

aInjectable triptan more effective than nasal or oral for cluster.

bSUNCT headaches are notably resistant to almost all treatments, some degree of response to triptans in a minority of patients has been seen.

• Preventive therapies that have been used with success include verapamil, prednisone, lithium, ergots, methysergide (use limited by side effects), cyproheptadine, and indomethacin; the last is also of special use in paroxysmal hemicranias and hemicranias continua (see Table 6.2-1).

• Surgery on the trigeminal nerve and deep brain stimulators have also been used in patients with refractory cluster headache.

• Complications of cluster include the risk of suicide, violent behavior, secondary depression, loss of function due to the intensity of pain, and side effects from treatments.

Patient Education

Patients with cluster headache are a highly motivated group. They need to be educated about acute treatments that can be self-administered, adherence to preventive regimens, and avoidance of triggers such as alcohol and nitrates.

TENSION-TYPE HEADACHES

Definition/Diagnosis

Tension headaches usually occur in the frontal and/or occipital areas in a bandlike pattern. They last 30 minutes to 7 days, are bilateral, and are of a non-pulsatile, tightening quality. Tension-type headaches (TTHs) are of mild to moderate intensity and do not get worse with routine exertion. Unlike migraine, they have mild (if any) nausea, and can have either photophobia or phonophobia (but not both). Cranial and muscular tenderness to palpation is the most significant finding, can be seen interictally, and helps differentiate from a migraine without aura. Infrequent episodic TTHs are considered benign, lasting 30 minutes to 7 days, and occurring at a frequency of less than 12 days per year. Frequent episodic TTHs occur more than 12 days per year, and they can evolve into chronic TTH, which occur more than 180 days per year.

Pathophysiology/Epidemiology

Previously TTHs were thought to be psychogenic in origin, but current data suggest peripheral nervous system mechanisms in episodic TTH, and a central mechanism in the chronic TTH subtype. TTH prevalence ranges from 30% to 78%, with a female-to-male ratio of about 1.3 to 1. However, chronic TTH prevalence is less than 5%. The more severe and chronic forms may be more common in patients with a family history of headaches.

Evaluation

Palpation of the scalp, temporalis, masseter, and paraspinal and trapezius muscles for tenderness.

Laboratory Studies and Imaging

ESR, CRP, and ANA are usually ordered to evaluate for vasculitis. Consider dissection.

Differential Diagnosis

TTHs that include either photo- or phonophobia can be mistaken for migraine. Medication-overuse headaches often complicate chronic tension headaches. Withdrawal of frequently used abortive medication can lead to reversion of chronic headaches to episodic pattern tension headaches. Chronic subdural hematoma should be suspected in elderly persons with new headaches or in those who have suffered head trauma.

Treatment

Aspirin, acetaminophen, and combinations containing one or both of these plus caffeine are often helpful for tension headaches. All nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) seem to be effective. Butalbital-containing combinations can be effective but have higher risk of rebound and abuse and may decrease the effectiveness of preventive medications. Muscle relaxant can sometimes be useful. Occasional use of tramadol or mild narcotics such as acetaminophen with codeine can be considered for more intense pain. Preventive therapy for chronic headaches is often indicated. Tricyclic class medicines have been used frequently. Selective serotonin–reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) may also be of use (Table 6.2-2). The application of heat, thermal biofeedback training, acupuncture, onabotulinum A injections, and physical modalities such as massage may all be considered.

Pharmacotherapy for Tension Headaches: Frequently Used Agents |

Agent | Therapeutic class |

Abortive treatments |

|

Aspirin | Salicylate |

Acetaminophen | NSAID-related |

Ibuprofen, Naproxyn, others | NSAIDs |

Toradol injectable | NSAID |

Aspirin/acetaminophen/caffeine | Salicylate/NSAID-related/combination |

Acetaminophen/caffeine | NSAID-related combination |

Isometheptene; dichioraiphenazone, and acetaminophen (Midrin) | Vasoconstrictor, muscle relaxant, NSAID-related/combination |

Butalbital/aspirin/caffeine | Barbiturate/salicylate combination |

Butalbital/acetaminophen/caffeine | Barbiturate/NSAID-related combination |

Tramadol (Ultram) | Atypical opioid |

Acetaminophen with codeine (Tylenol #3, others) | Opioid derivative, NSAID-related combination |

Preventive treatments |

|

Amitriptyline (Elavil), nortriptyline (Pamelor), others | Tricyclic antidepressant |

Prozac, others | SSRI |

Tizanidine (Zanaflex) | Antispasmodic, central α2-adrenergic agonist |

Complications

Anxiety and depression are both comorbid with chronic headaches. Whether the headaches have any causative role is unclear.

Patient Education

For mild episodic headaches, patients should be taught to use the safest effective medication on a prn basis. Education about the avoidance of medication overuse to minimize the risk of rebound headaches is warranted. Patients with chronic headaches should be taught the value of prophylactic medications. If chronic headaches persist, then patients should be given the opportunity to seek care at a specialized headache center.

OTHER IMPORTANT HEADACHE SYNDROMES

• Chronic daily headaches. Daily headaches occur in up to 5% of the population, and the differential includes chronic migraine (CM), chronic TTH, medication-overuse headache, new daily persistent headache and secondary headache syndromes. Both CM and chronic TTH require a headache frequency of at least 15 days per month. New daily persistent headache is daily and unremitting from the first onset (which is clearly remembered by the patient) lasting for more than 3 months. The most common cause of daily headaches is CM. CM is diagnosed as headache (tension-like or migraine-like) on more than 15 days per month for 3 months, with migrainous features at least 8 days per month. The best studied treatment paradigm for CM was through two randomized studies (PREEMPT I and II) of onabotulinum toxin A (Botox) injections in 31 prespecified sites, showing a significant reduction of headache days by about half.

• Hypnic headaches. These headaches are moderate to severe, occur nightly, and awaken patient from sleep, 2:1 female-to-male ratio. They last ~1 hour and are not associated with autonomic symptoms. Intracranial disorders should be excluded by neuroimaging such as MRI. Caffeine and lithium have been reported as effective treatments.

• Neuropathic or cervicogenic headaches. The head pain originates in cervical spine (usually C1–3) and is usually unilateral without side-shifting, ablated by treating underlying pathology or temporarily by occipital and/or upper cervical nerve blocks.

• Posttraumatic headaches. They resemble tension headaches but within 7 days after head trauma and are often the most prominent symptom of a whole postconcussive syndrome that may include dizziness, memory, and personality disturbances.

• Exertional, cough-, and sex-associated headaches. All associated with conditions that raise intra-abdominal pressure. More than 40% have some intracranial abnormality usually vascular (such as SAH), or tumor, so complete workup and imaging such as MRI/MRA is indicated. Indomethacin is often helpful. There are some reports of β-blockers being effective. Consider angina in differential of sex-associated headaches as anginal symptoms may be noted only in the head and neck in some patients.

• Stabbing (ice-pick) headaches. Stabbing pains last up to a few seconds one to many times a day, and are felt in orbit, temple, and parietal areas in the distribution of the first division of the trigeminal nerve. There are no associated autonomic symptoms. These headaches occur more commonly in patients with other headache types such as migraine or cluster. If strictly in one area, structural lesion should be excluded by imaging.

• Idiopathic intracranial hypertension (formerly called pseudotumor cerebri or benign intracranial hypertension). This includes progressive diffuse headache, usually daily, non-pulsating, and aggravated by straining or cough. Papilledema, visual defects, and field defects are common. Elevated CSF pressure is detected by lumbar puncture. Typical patient is a young obese woman. Oral contraceptives, tetracycline, and many other drugs are risk factors.

REFERENCES

1. Castillo J, Munoz P, Guitera V, et al. Epidemiology of chronic daily headache in the general population. Headache 1999;39:190–196.

2. Diamond S. Tension-type headache. Clin Cornerstone 1999;1(6):33–44.

3. Dodick DW. Chronic daily headache. N Engl J Med 2006;354:158–165.

4. Sandrini G, Tassorelli C, Ghiotto N, et al. Uncommon primary headaches. Curr Opin Neurol 2006;19(3):299–304.

5. Sjaastad O, Fredriksen TA. Cervicogenic headache: criteria, classification and epidemiology. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2000;18(Suppl 19):S3–S6.

6. Smetana GW. The diagnostic value of historical features in primary headache syndromes. Arch Intern Med 2000;160:2729–2737.

7. International classification of headache disorders, 3rd edition. Cephalalgia 2013;33(9):1–180.

8. Bigal ME, Serrano D, Reed M, et al. Chronic migraine in the population: burden, diagnosis, and satisfaction with treatment. Neurology 2008;71:559–566.

9. Diener HC, Dodick DW, Goadsby PJ, et al. Chronic migraine—classification, characteristics and treatment. Nat Rev Neurol 2012;8:162–171.

10. Bendtsen L, Bigal ME, Cerbo R, et al. Guidelines for controlled trials of drugs in tension-type headache: second edition. Cephalalgia 2010;30:1–16.

11. Fernandez-de-Las-Penas C, Schoenen J. Chronic tension-type headache: what is new? Curr Opin Neurol 2009;22:254–261.

12. Bahra A, May A, Goadsby PJ. Cluster headache: a prospective clinical study in 230 patients with diagnostic implications. Neurology 2002;58:354–361.

|

GENERAL PRINCIPLES

Meningitis, clinically characterized by fever, headache, and meningismus, consists of inflammation of meninges and the subarachnoid space with evidence of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) pleocytosis. Acute meningitis presents within hours to days, whereas chronic meningitis is longer than 4 weeks. Meningitis can be divided into three categories: pyogenic (bacterial), aseptic, and granulomatous.

Epidemiology and Etiology of Acute Meningitis1–3

Mortality from bacterial meningitis is still high (20% in adults and lower in children). The most likely pathogens causing acute bacterial meningitis depend on several factors, including age and immunocompromised status among others. Most common pathogens are:

• Streptococcus pneumoniae

• Can affect all age groups

• Risk factors: immunoglobulin alternative complement deficiency, asplenia, and alcoholism

• Constitutes about 57% of meningitis cases

• Neisseria meningitides

• Affects adolescents and younger adults

• Risk factor: multiperson dwelling

• 17% of meningitis

• Listeria monocytogenes

• Affects neonates and adults

• Risk factor: cell-mediated immunodeficiency

• 4% of cases

• Haemophilus influenza

• Affects children and adults

• Risk factor: new born

• 6% of cases

• Group B streptococcus

• Neonates

• Risk factor: age <2 months

• 17% of cases

• Gram-negative rods

• Affects adults

• Mostly a nosocomial infection

• 33% of all nosocomial meningitis

• Others such as Staphylococcus aureus, Pseudomonas, Serratia, and fungi can affect immunocompromised or neutropenic patients.

Etiology of Subacute and Chronic Meningitis2

• Mycobacterial causes include Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Mycobacterium avium–intracellulare complex (in HIV patients).

• Spirochetal organisms causing subacute meningitis are Treponema pallidum and Borrelia burgdorferi.

• Fungal causes include Cryptococcus neoformans, Coccidioides immitis, Blastomyces dermatitidis, Histoplasma capsulatum, and Aspergillus.

• Viral organisms (aseptic, usually acute) causing meningitis include West Nile virus, herpesvirus types 1 and 2, echovirus, Coxsackie virus types A and B, Enterovirus, mumps, lymphocytic choriomeningitis, Epstein–Barr virus, cytomegalovirus, and arthropod-borne viruses.

• Parasitic organisms include Naegleria and Angiostrongylus.

DIAGNOSIS1–3

Clinical Features

• The diagnosis of meningitis should be considered in patients with fever, altered mental status, and meningeal signs and symptoms. In bacterial meningitis, patients (mostly children) may have a precedent upper respiratory tract infection, otitis media, or pneumonia. The presence of rash may help defining the etiology. Meningeal signs and symptoms include the following:

• Generalized headache (new onset), nuchal rigidity, vomiting, photophobia, and seizures (20% of acute bacterial meningitis) changes in mental status (coma being the extreme) can be signs of meningeal infection.

• In the neonates, fever, decreased appetite, irritability, vomiting, or lassitude should alert the physician to consider meningitis. In elderly patients, signs of meningismus can be absent.

• Clinical examination in acute bacterial meningitis may reveal an ill-looking, toxic, febrile individual with neck rigidity and a positive Kernig or Brudzinski sign. Other possible signs include altered mental status and cranial nerve palsies (particularly involving nerves III, IV, VI, and VII). Focal neurologic signs include hemiparesis, monoparesis, and hemianopia among others. In subacute meningitis, these classic signs may be absent, and the patient may have fever and altered mental status only. In infections due to N. meningitidis, a rapidly developing, purplish skin rash may be seen.

Laboratory Diagnosis

• CSF examination

• Elevated opening pressure is found in acute meningitis (greater than 18 cm H2O), mostly of bacterial origin.

• Purulent fluid with high polymorphonuclear cell count, increased protein, and low glucose indicates acute bacterial meningitis. Perform Gram stain and consider latex agglutination antigen testing to identify the organism. Culture of CSF will specifically identify the offending pathogen.

• High lymphocyte count in the CSF with a normal glucose level is commonly seen in viral meningitis or partially treated pyogenic bacterial meningitis.

• High lymphocyte count in the CSF with a low glucose level is commonly seen in tuberculosis and fungal meningitis.

• Other laboratory tests. Two blood cultures, complete blood count, serum electrolytes, and radiologic studies of the chest or computed tomography (CT) scanning of the sinuses may be considered in certain clinical situations. CT scanning or MRI of the brain is essential, particularly in the absence of papilledema and before performing a lumbar puncture to look for signs of increased intracranial pressure.

Empirical antimicrobial therapy should be started immediately, preferably within 30 minutes of diagnosis. In addition, corticosteroid use has been shown to reduce morbidity and mortality (bacterial meningitis in children) and improve functional outcome (adults).

Empirical Antibiotic Treatment

• Neonates (0 to 4 weeks) can be treated with ampicillin 150 to 200 mg per kg IV daily divided every 8 hours, and gentamicin 2.5 mg per kg q8–12h or cefotaxime (Claforan) 50 mg per kg IV q8h.

• Children, adolescents, and adults (5 weeks to 55 years) may be treated with one of the following regimens:

• For children, cefotaxime 300 mg per kg of body weight IV divided every 6 hours or ceftriaxone 100 mg per kg body weight IV in two divided doses with vancomycin 60 mg per kg body weight/day IV in three divided doses.

• For adults, cefotaxime 2 g q4–6h IV or ceftriaxone 2 g q12h IV with vancomycin 30 to 45 mg per kg q12h IV.

• Patients older than 55 years can be treated with ampicillin 2 g IV q4h, vancomycin 1 g q12h IV, and cefotaxime or ceftriaxone. Patients allergic to penicillin can be treated with chloramphenicol 4 to 6 g divided every 6 hours, or trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole (Bactrim) 10 to 20 mg/kg/day in four divided doses with gentamicin 5 mg per kg IV per day divided every 8 hours.

• Adjunctive therapy. Corticosteroids, such as dexamethasone 0.15 mg per kg of body weight q6h for 4 days, are recommended for patients with acute onset community acquired meningitis. Respiratory isolation for 24 hours is recommended in patients with suspected N. meningitides infection.

• Specific therapy. Once the specific pathogen is identified, specific cost-effective antibiotics should be substituted for empirical therapy.

• S. pneumoniae. For infection in adults, give penicillin 4 million U IV q4h. Children should receive 0.3 million units divided every 4 to 6 hours not to exceed 24 million U. Alternatives are chloramphenicol or a third-generation cephalosporin. For penicillin-resistant pneumococci, give cefotaxime or vancomycin 1 g q12h IV.

• S. aureus. For adults, give nafcillin 2 g q4h IV. For children, give 100 to 300 mg per kg of body weight IV in four divided doses. In case of methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) infection, give vancomycin.

• L. monocytogenes. Give penicillin or ampicillin plus gentamicin. Alternative therapy is chloramphenicol or trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole plus gentamicin.

• H. influenzae. For β-lactamase-negative infections, give ampicillin; for β-lactamase-positive infections, give cefotaxime or ceftriaxone.

• N. meningitidis. Give penicillin or ceftriaxone, cefotaxime, or chloramphenicol.

• E. coli or Enterobacteriaceae. Give cefotaxime or ceftriaxone plus gentamicin.

• Tuberculosis. Give a combination of isoniazid (INH), rifampin, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol, or streptomycin for 2 months, then INH and rifampin for an additional 10 months.

• Fungal etiology. Give amphotericin B 1 mg per kg of body weight IV or liposomal amphotericin 5 mg per kg of body weight IV and 0.05 to 0.10 mg intrathecally of amphotericin B with or without flucytosine (5-FC, Ancobon), 150 mg per kg of body weight daily in divided doses. An alternative is fluconazole (Diflucan) 400 to 1,000 mg PO or IV, or voriconazole 200 mg PO or IV q12h, in Cryptococcus or Coccidioides meningitis.

• Duration of therapy. Treatment of common bacterial meningitis continues for 7 days for H. influenzae and N. meningitis, 10 to 14 days for S. pneumoniae, 14 to 21 days for group B streptococci, and 21 days for Gram-negative bacilli (other than H. influenzae) and 21 days or longer for L. monocytogenes.

Prevention

• Meningococcal meningitis. Contacts should be given rifampin 600 mg PO q12h for 2 days. Pregnant patients can be given 250 mg of ceftriaxone IM. Meningococcal conjugate vaccine is now recommended by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) at ages 11 to 12 years with a booster at age of 16 years. It is also recommended for travelers to countries with high incidence of meningococcal disease, patients with anatomic or functional asplenia, and patients with terminal complement deficiency.

• H. influenzae meningitis. Contacts younger than 12 months should receive rifampin 20 mg per kg of body weight for 4 days.

REFERENCES

1. Bratt R. Acute bacterial and viral meningitis. Continuum (Minneap Minn) 2012;18(6):1255–1270.

2. Zunt J, Bladwin K. Chronic and subacute meningitis. Continuum (Minneap Minn) 2012;18(6):1290–1315.

3. van de Beek D, de Gans J, Spanjaard L, et al. Clinical features and prognostic factors in adults with bacterial meningitis. N Engl J Med 2004;351:1849–1859.

4. Feigin RD, McCracken GH Jr, Klein JO. Diagnosis and management of meningitis. Pediatr Infect Dis J 1992;11:785–814.

5. van de Beek D, de Gans J, Tunkel AR, et al. Community-acquired bacterial meningitis in adults. N Engl J Med 2006;354:44–53.

6. Tunkel AR, Hartmann BJ, Kaplan SL, et al. Practice guidelines for the management of bacterial meningitis. Clin Infect Dis 2004;39:1275.

|

DEFINITION

A seizure is a transient event that includes symptoms and/or signs of abnormal excessive hypersynchronous activity in the brain. These symptoms/signs could manifest in the form of motor, sensory, autonomic, cognitive, or experiential phenomena. The traditional definition of epilepsy requires the occurrence of at least two unprovoked seizures.1

CLASSIFICATION AND CLINICAL PRESENTATION1

The International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE-1981) divides seizures into three major categories: partial (or focal), generalized (convulsive or nonconvulsive), and unclassified epileptic seizures. Generalized seizures can be convulsive or nonconvulsive and are divided into six types. Partial seizures can begin with a warning (aura) that reflects a focal brain onset, associated with localized symptoms (motor, sensory, autonomic, or psychic). They can remain localized (simple) or spread (secondary generalized seizure), or be associated with altered consciousness (complex). Ictal apnea, incontinence, tongue biting, or significant injury, especially a fracture or a broken tooth, or postictal headache, lethargy, confusion, or Todd paralysis, is usually suggestive of epileptic seizures instead of a nonepileptic spell. The highest incidence of seizures is in children (usually younger than 5 years) and elderly individuals. In this chapter, we will not discuss the classification of epilepsies.

Generalized Seizures

• Tonic–clonic (grand mal): The onset is abrupt with loss of consciousness followed by major motor activity (tonic contraction then clonic activity), apnea, and occasional cyanosis, often heralded by a brief epileptic cry but without an aura. Postictal confusion with stertorous respiration. They can represent the manifestation of idiopathic generalized epilepsy or other epileptic syndromes. Isolated provoked (hypoglycemia, prolonged sleep deprivation, others) seizures are also to be considered.

• Clonic: An isolated jerk or a cluster of jerks. Frequently seen in epileptic syndromes.

• Tonic: Usually brief (<1 minute) contraction of trunkal and/or extremity muscles.

• Atonic seizures cause sudden loss of muscle tone and often result in severe trauma. They can be associated with epileptic syndromes (e.g., Lennox–Gastaut).

• Myoclonic seizures are repetitive brief muscle contractions associated with ictal electroencephalographic (EEG) change affecting a single or multiple muscle groups (trunk, extremities). They can be seen with idiopathic generalized epilepsies or with epileptic syndromes.

• Absence seizures

• Typical simple absence seizures (petit mal) are characterized by abrupt psychomotor arrest usually lasting less than 15 seconds with no postictal state. They typically occur multiple times a day. Complex absence seizures can be associated with minor motor manifestations (e.g., eye blinking or lip smacking). Onset of absence epilepsy is usually after age 3 years and peak incidence is between ages 5 and 10 years. Most absence seizures resolve by early adulthood.

• Atypical absence seizures (associated with hypotonia or atonia) are common in the Lennox–Gastaut syndrome and other epileptic syndromes and conditions.

Partial Seizures

Partial seizures are always focal in onset but often spread to become generalized. Because of the possibility of an underlying central nervous system lesion, an effort to detect an aura or a sign of focal onset is required in all generalized seizure cases.

• Simple: Do not cause loss of consciousness. Can originate from the temporal, frontal, parietal, or occipital lobe.

• Motor seizures can present with a Jacksonian march, aphasia, or postural. Benign Rolendic epilepsy presents with focal motor seizures (mostly involving the face) during childhood.

• Sensory seizures can be visual, auditory, verbal, gustatory, somatic, or vertiginous.

• Autonomic: Nausea, vomiting, pallor, changes in heart rate, diarrhea, and diaphoresis among other manifestations.

• Complex: Associated with altered consciousness and most commonly are of temporal lobe origin.

DIAGNOSIS

Diagnostic evaluation varies according to clinical presentation. In general, the following tests are recommended following a single provoked or unprovoked seizure:

• Electroencephalography. Although it is the most useful test, the EEG is not always diagnostic. Activation procedure (hyperventilation, sleep deprivation, and photic stimulation during EEG recording), ambulatory recordings, videotaping, or repeat EEG improves diagnostic accuracy. A generalized three per second spike-and-wave discharge is diagnostic of idiopathic generalized absence epilepsy. Partial complex seizures usually show a focal abnormality on the EEG.

• Blood tests, looking for secondary etiologies for acute seizures. Serum electrolytes (especially sodium), calcium, magnesium, blood urea nitrogen, glucose, liver function tests—bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase, aspartate aminotransferase (serum glutamate oxaloacetate transaminase)—complete blood count, and, when indicated, toxin screens and alcohol level are sometimes diagnostic. A prolactin level is not usually considered in the workup.

• Imaging studies. Magnetic resonance imaging is the preferred study, but computed tomography can be done emergently looking for the possibility of intracerebral hemorrhage or other pathologies. Brain imaging should be considered in patients with focal neurological deficit and in the elderly.

• Lumbar puncture is indicated if infection or subarachnoid hemorrhage is suspected.

• Anticonvulsant levels are considered when control of seizures is poor, when drug toxicity is suspected, and within 2 weeks after drug dosage is changed or potentially cross-reacting drugs are added.

MORTALITY AND MORBIDITY

The more frequent the seizures, the higher the likelihood of secondary illness, with increased incidence of psychiatric disorders and migraine headaches with epilepsy. There is a three-time increased mortality rate compared to the general population, including the risk of sudden unexplained death in epilepsy.

TREATMENT

Treatment applies to secondary seizures (treat the underlying cause) and to epilepsy (with antiepileptic drugs, AEDs). A single unprovoked seizure does not require treatment with AEDs. The following are the general principles:

• Correction of blood chemistry abnormalities and combating inciting agents, such as drugs or infections, is essential. Identifying and avoiding triggers (such as alcohol) is also a key.

• Hyponatremia. Seizures or coma occur only if serum sodium is extremely low. Hypertonic saline is best avoided. Slow correction at the rate of 12 mEq per day avoids central pontine myelinolysis.

• Hypocalcemia requires one or two ampoules of calcium gluconate (90 mg per ampoule), IV over 5 to 10 minutes.

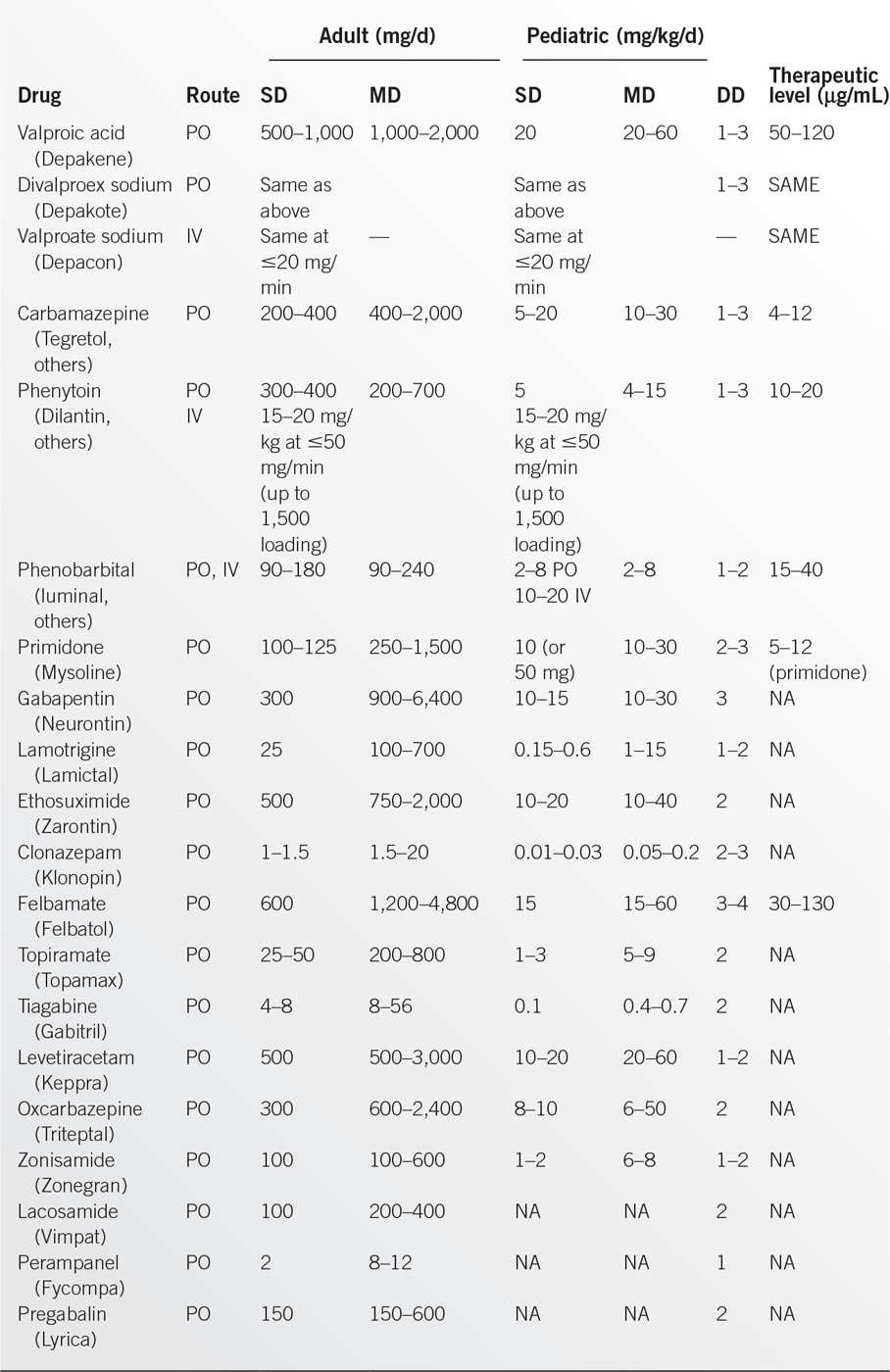

• AEDs are presented in Table 6.4-1; dosages are given below.2–4 Drugs of choice are listed in Table 6.4-2.2,4,5

• Acetazolamide (Diamox), pyridoxine, adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), biotin, or a ketogenic diet is useful under special circumstances.

• During pregnancy, AED treatment should be continued. Folic acid supplements may reduce birth defects.

• Rectal diazepam is useful to achieve rapid seizure control, even in the home environment, especially for febrile convulsions.

• Vagal nerve stimulation and responsive neurostimulation can improve seizure control mostly in partial epilepsy refractory to medical treatment.

• Epilepsy surgery can provide excellent outcome in selected patients with partial epilepsy refractory to medical treatment.

STATUS EPILEPTICUS

Status epilepticus is broadly defined as continuous or repetitive convulsions lasting for 30 minutes or recurrent seizures without recovery of consciousness. It is recommended that vigorous therapy for status epilepticus be initiated after 5 minutes of generalized tonic–clonic activity.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree