Infectious Mononucleosis

A usually benign disease characterized by fever, malaise, LAP, and tonsillitis. Patients may have hepatosplenomegaly and generalized maculopapular rash. The illness usually resolves in 1 to 4 weeks, but complications such as secondary infection, meningitis, encephalitis, myelitis, and Guillain–Barre syndrome can occur.

Burkitt Lymphoma

Burkitt lymphoma is endemic in Africa. It often presents as a tumor of the jaw and face in children. For unknown reasons, it is rarely seen in other parts of the world.

Nasopharyngeal Cancer

This disease occurs in Alaska, South China, and East Africa. It may present as a neck mass due to cervical nodal metastasis, nasal obstruction with epistaxis, or headache caused by cranial nerve involvement.

Oral Hairy Leukoplakia

It is an opportunistic infection in HIV patients. It presents as white corrugated painless plaques that cannot be scraped off, mainly on lateral sides of tongue. Other parts of the oral cavity may be involved such as soft palate and buccal mucosa. It is specific to HIV, and is not seen in patients with other kinds of immunodeficiency.

Diagnosis

The most common laboratory finding in IM is lymphocytosis with absolute count >4,500 per μL or differential count of more than 50%, and it is also associated with atypical lymphocytes >10%. A latex agglutination test (monospot test) is readily available and detects heterophile antibodies.

Treatment

Primary treatment of most EBV infections is supportive. Acetaminophen or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents are recommended for fever or pain.

CYTOMEGALOVIRUS

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection has affected nearly 50% of the U.S. population by age 35. It is transmitted sexually, or via saliva, urine, or by blood transfusion.

It is usually asymptomatic, but in patients with organ transplant or other immunosuppressive diseases such as AIDS it can cause retinitis, esophagitis, pneumonitis, encephalitis, or colitis.

CMV Mononucleosis

It is a syndrome closely resembling IM in immunocompetent individuals. Systemic symptoms such as fever are more prominent than cervical LAP or splenomegaly compared with IM.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis includes enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) testing or characteristic inclusion bodies in biopsy specimens. Detection of CMV specific IgM antibodies suggests recent seroconversion. PCR testing for quantifying CMV DNA is widely available for diagnosis or monitoring of these patients.

Treatment

Treatment is symptomatic in immunocompetent patients. Ganciclovir is used especially in treatment of retinitis. Foscarnet can also be used. Acyclovir is not recommended.

VARICELLA (CHICKENPOX)

This virus is highly infectious and 90% of susceptible household contacts with the patient will become infected. Spread is primarily by respiratory secretions (cough and sneeze) or through direct contact with skin lesions.

Chicken pox has an incubation period of 14 to 16 days after contact with a varicella or herpes zoster patient. This is followed by a prodrome of fever and malaise for 1 to 2 days, and then appearance of the characteristic rash. The disease is more severe in older children and adults, especially if they are immunocompromised. Fifteen percent of adolescent or adult patients with varicella may develop pneumonia. Other complications are fulminant encephalitis, cerebellar ataxia, and, rarely, transverse myelitis and aseptic meningitis. Recovery from infection provides immunity for life.

Congenital varicella syndrome occurs in 2% of affected pregnancies, with limb hypoplasia, ocular atrophy, and psychomotor retardation. It may be caused by an infection in utero during first trimester of pregnancy. Neonatal varicella occurs when the mother develops varicella around the time of delivery; it has mortality up to 30%.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is primarily by history of exposure and presence of characteristic rash. Rash is generalized and pruritic and starts from head and face and spread to chest and back and then spread to rest of the body. It starts as maculopapular rash and rapidly changes to vesicles that subsequently crust. The rash is concentrated mainly on chest and back and is in different stages of evolution simultaneously.

Treatment

Symptomatic treatment with antihistamines and acetaminophen is recommended. Aspirin should be avoided as it may lead to Reyes syndrome. Acyclovir is recommended within 24 hours of appearance of rash in patients 12 years of age or older, those with chronic pulmonary disorders, or patients receiving immunosuppressive treatment such as steroids. Acyclovir may be considered for prophylaxis of secondary household contacts within 24 hours without preexisting immunity. Intravenous acyclovir should be used in immunocompromised hosts. Passive immunization with varicella zoster immune globulin (VZIG, 1 vial 5 = 125 units = 1.25 mL, 125 units per 10 kg up to 625 units, with minimum of 1 vial, IM), administered within 96 hours of a significant exposure, is indicated for neonates, pregnant women, and immunocompromised patients.

HERPES ZOSTER (SHINGLES)

Reactivation of varicella zoster virus occurs, often unpredictably, or among those with immunosuppressive conditions. Zoster usually manifests as radicular pain in the affected nerve segment, followed by vesicular lesions after few days in the discrete areas of that dermatomal nerve segment. New lesions may appear in adjacent dermatomes. Involvement of the ophthalmic branch of cranial nerve V may cause visual impairment or blindness, uveitis, keratitis, or conjunctivitis, whereas involvement of CN 7 and 8 can lead to Bell palsy or Ramsay–Hunt syndrome (facial palsy, tinnitus, vertigo, and impairment of taste and hearing), respectively. The presence of the Hutchinson sign (vesicles on the side and tip of the nose) is an indication that ocular involvement is likely, and slit-lamp examination is mandatory. Postherpetic neuralgia (PHN) is characterized by pain persisting 4 to 6 weeks beyond crusting of lesions. It is more common in older patients, occurring in more than 50% of persons older than 60 years.

Diagnosis

History of chickenpox, herpes zoster, or lack of varicella immunization in the past with the appearance of characteristic rash helps make the diagnosis. The lesions are vesicular with an erythematous base. Definitive diagnosis can be made by culture of the virus from the lesion.

Treatment

Supportive care includes analgesics and wet compresses with water or a 5% Burlow solution may be helpful. The use of nucleoside analog (acyclovir and valacyclovir) within 72 hours of appearance of the rash is recommended (see Table 19.8-2). Systemic steroids have demonstrated no additional benefit in reduction of PHN. Studies examining amitriptyline, narcotics, capsaicin, anticonvulsants, and percutaneous nerve stimulation for PHN have been inconclusive.

Patients with eye involvement should be referred to an ophthalmologist.

REFERENCES

1. Hunt R. Virology, Chapter 11. Herpes Virus. http://pathmicro.med.sc.edu/virol/herpes.htm.

2. CDC.gov

3. Wenner C, Nashelsky J. Antiviral agents for pregnant women with genital herpes. Am Fam Physician 2005;72:1807.

4. Holten KB, Britigan DH. Treatment of herpes zoster. Am Fam Physician 2006;73:882.

5. Patel R. Antiviral agents for the prevention of the sexual transmission of herpes simplex in discordant couples. Curr Opin Infect Dis 2004;17:45–48.

6. Brady RC, Bernstein DI. Treatment of herpes simplex virus infections. Antiviral Res 61:73–81.

|

GENERAL PRINCIPLES

Lyme disease is a tick-borne illness transmitted by the bite of certain Ixodes ticks. It is caused by the bacterial spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi in the United States, whereas other species of Borrelia cause the disease in Europe. Lyme disease is a multisystem illness manifesting initially as a systemic and dermatologic condition. If not treated, the infection can lead to rheumatologic, neurologic, or cardiac sequelae.

Definition

Any infection with B. burgdorferi can be considered Lyme disease. Infection can range from asymptomatic seroconversion to severe neurologic sequelae.

Pathophysiology (Epidemiology)

Lyme disease was first discovered in the 1970s, with standardized case definitions developed in 1991. In the United States, most cases occur in New England, the mid-Atlantic states, and in Minnesota and Wisconsin, with less frequent cases along the Pacific coast in Oregon and Northern California.1,2 The incidence has been increasing over the past decade. Mice, chipmunks, and birds are natural reservoirs for the spirochete, and ticks acquire the bacteria by feeding on infected animals. Deer are not competent hosts, but they do play a role in sustaining the life cycle of the ticks.2

DIAGNOSIS

Clinical Manifestations

Early disease is characterized by the erythema migrans (EM) rash, which occurs 3 to 30 days after the tick bite. The rash occurs at the site of the bite and classically expands with a ring of central clearing,2 hence the description target lesion. However, the lesion can be uniformly erythematous or have enhanced central erythema. Systemic flu-like symptoms including fever, fatigue, and myalgia often accompany the rash.

If untreated, the organism can spread hematogenously, leading to early disseminated disease. This stage presents with multiple, smaller EM lesions and/or central nervous system (CNS) involvement, Lyme neuroborreliosis. Common CNS manifestations are cranial nerve palsy or lymphocytic meningitis. Systemic symptoms of myalgias, arthralgias, headache, and fatigue may also occur in this phase with cardiac complications such as atrioventricular node block or carditis being less common.

Late Lyme disease occurs weeks to months after initial infection and presents as a monoarticular arthritis, most often of the knee. This is seen less commonly because most affected people are treated prior to this stage.2,3

History

History should focus on potential exposure, including geographic location and possibility of tick bite. If this is present, timing of clinical symptoms, including rash, systemic, neurologic, cardiac, and rheumatologic symptoms, should be explored.

Physical Examination

Physical examination should focus on the systems involved in the disease process as well. A thorough skin examination, neurologic examination including cranial nerve testing, and musculoskeletal examination are important. Vital signs (pulse and blood pressure) and cardiac auscultation are necessary to determine whether there is cardiac involvement.

Laboratory Studies

Serologic testing in a two-tiered approach with screening enzyme immunoassay or immunofluorescent assay and confirmatory Western immunoblot is recommended. However, the testing lacks sensitivity in early Lyme as IgM antibodies can take 3 to 4 weeks to develop.2,3 Thus, history of potential exposure and presence of EM rash is sufficient for diagnosis and initiating treatment. Serologic testing is helpful when illness has been present for several weeks and/or the diagnosis is in question.

If there is CNS involvement, antibody testing should be done on cerebrospinal fluid (CSF).1,3 PCR is available for detection in the CSF or in synovial fluid, but it lacks sensitivity and is not currently recommended.4,5

Mildly elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate and liver enzyme testing may be seen. In neuroborreliosis, CSF may show a lymphocytic pleocytosis and mildly elevated protein.

Genetics

There is currently no evidence that there is a genetic predisposition to Lyme disease or its sequelae.

Differential Diagnosis

The disease that most closely mimics cutaneous Lyme disease is Southern Tick Associated Rash Illness (STARI), which occurs in southern and south central United States. STARI does not have any of the other features of Lyme such as neurologic or rheumatologic manifestations. The differential diagnosis for EM includes nummular eczema, cellulitis, insect or spider bite, granuloma annulare, tinea corporis, erythema multiforme, and urticaria. When symptoms are more systemic, Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever, relapsing fever, Colorado tick fever, babesiosis, tularemia, ehrlichiosis, and syphilis should be considered. Differential diagnosis of Lyme arthritis includes septic arthritis, reactive arthritis, and inflammatory arthritis. Coinfection with Babesia, Anaplasma, Ehrlichia, deer tick virus, or other species of Borrelia can occur.2

TREATMENT

Medications

For early disease including localized or disseminated, uncomplicated arthritis or cranial nerve palsy, doxycycline 100 mg orally twice daily is recommended for adults and children 8 years of age and over. For children under 8 years old, amoxicillin 50 mg/kg/day orally divided three times daily up to 1,500 mg is recommended; if penicillin allergic, cefuroxime 30/mg/kg/day orally divided twice daily up to 1,000 mg is recommended. Recommended length of therapy is 14 to 21 days.3 For meningitis, IV therapy with either ceftriaxone 2 g IV daily (50 to 75 mg/kg/day pediatric dose) or cefotaxime 2 g IV every 8 hours (150 to 200 mg/kg/day pediatric dosing) is the recommended treatment for a total of 14 to 28 days. For complicated arthritis or carditis, either oral or IV therapy is recommended. One-time treatment with doxycycline within 72 hours of removal of deer tick has been studied and can be effective, but there are currently no recommendations to treat empirically as such.2

Complications

There is a debate about whether chronic Lyme or post-Lyme syndrome is a true clinical phenomenon. Chronic Lyme implies continued infection with B. borgdorferi despite antibiotic treatment, which has not been demonstrated in studies. Thus, the term post-Lyme syndrome has been used to describe the symptoms of arthralgia, myalgia, sleep disorders, and difficulty with concentration that some patients describe. Some studies suggest that there may be an autoimmune or other immunogenic mechanism causing this syndrome, whereas others indicate that incidence of this nonspecific constellation of symptoms is no higher in patients treated for Lyme than it is in the general population or following other infections and thus may not be an actual clinical entity. There is currently no evidence for prolonged antibiotic treatment for these late symptoms.6

Patient Education

Avoiding tick bites in endemic areas by wearing long pants and shirts, using at least 20% N, N-diethyl-meta-toluamide (DEET) and frequent checking for ticks is important for prevention. Educating patients about signs and symptoms of Lyme disease can lead to earlier presentation and treatment. A previous vaccination, LYMErix was on the market from 1998 to 2002 but was withdrawn by the manufacturer. The vaccine was directed against the outer surface protein A (Osp A) and there are currently new Osp A vaccines being studied.7,8

REFERENCES

1. Graham J, Stockley K, Goldman R. Tick-borne illnesses: a CME update. Pediatr Emerg Care 2011;27:141–7.

2. Shapiro ED. Clinical practice. Lyme disease. N Engl J Med 2014;370:1724–31.

3. American Academy of Pediatrics. Lyme disease (Lyme borreliosis, Borrelia burgdorferi infection). In: Pickering LK, ed. Red book: 2012 report of the Committee on infectious diseases. 29th ed. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2012:474–479.

4. Nelson CA. CDC Expert Commentary. PCR for Diagnosis of Lyme Disease: Is It Useful? Medscape website. http://www.medscape.com/partners/cdc/public/cdc-commentary. Accessed on June 11, 2012.

5. CDC. Notice to readers: Caution regarding testing for Lyme disease. MMWR. Morb Mortal Wkly Rsp 205; 54: 125. http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/764501.

6. Sordet C. Chronic Lyme disease: fact or fiction? Joint Bone Spine 2014;81:110–1.

7. Lantos PM. Lyme disease vaccination: are we ready to try again? Lancet Infect Dis 2013;13:643–4.

8. Stricker RB, Johnson L. Lyme disease vaccination: safety first. Lancet Infect Dis 2014;14:12.

|

GENERAL PRINCIPLES

Definition

Rocky Mountain spotted fever (RMSF) is a potentially fatal, tick-borne illness caused by Rickettsia rickettsii.

Epidemiology

• Most prevalent in the southeastern and south central states

• 2,221 cases of RMSF reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in 20101

• Incidence is highest among persons aged 40 to 64 years2

• Most common between the months of April and September

• Two principal vectors for bacterial transmission within the United States

• The wood tick (Dermacentor andersoni) in the western United States

• The dog tick (Dermacentor variabilis) in the eastern and southern United States

Etiology

RMSF is caused by the Gram-negative obligate intracellular bacterium R. rickettsii.

DIAGNOSIS

Clinical Presentation

• Based on clinical signs and symptoms after an incubation period of 4 to 12 days (mean 7 days).

• Classic presentation is rapid onset of headache and fever followed in 2 to 3 days by rash.

• Other symptoms are nonspecific and may include myalgias, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain (especially in children) malaise, sore throat, nonproductive cough, and pleuritic chest pain.

• Classic triad of fever, headache, and rash present in less than 50% of cases at initial presentation.3,4

History

A tick bite is recalled by 50% to 70% of patients.

Physical Examination

• Rash initially appears on the distal extremities (palms, soles, wrists, ankles, and forearms) and consists of small, pink, blanchable macules.

• Rash later spreads centripetally to the trunk, neck, and face.

• Lesions become maculopapular and petechial and may then coalesce and form large ecchymotic areas and ulcerations.

• From 5% to 15% of patients may never develop a rash.5

Laboratory Studies

Laboratory studies include primarily a clinical diagnosis as there are no completely reliable tests in the early phase of illness when therapy should be initiated.

• Skin biopsy

• May be used if rash is present, however, very few laboratories have the ability to perform, so often of little or no use in initial patient management

• 100% specific and 60% sensitive (very low sensitivity once treatment has been initiated)6

• Serologic testing

• Confirmation may be done using indirect fluorescent antibody testing.7

• Overall sensitivity is 95% and is available through most state health departments.

• False negatives may occur during the first 5 days of symptoms as antibody response is not yet detectable, or if treatment is initiated within 48 hours of symptom onset as these patients may never develop an antibody response.

• General laboratory testing is nonspecific but may reveal thrombocytopenia, hyponatremia; elevated liver transaminases; azotemia; and an increased, decreased, or normal white blood cell count.

Differential Diagnosis

Measles, meningococcemia, streptococcal infection, parvovirus infection (Fifth disease), roseola, enteroviral infection, viral meningitis, ehrlichiosis, drug reaction, infectious mononucleosis, leptospirosis, immune thrombocytopenic purpura, immune complex vasculitis, or bacterial sepsis.

TREATMENT

Medications

• Antibiotics should be initiated immediately when there is suspicion of RMSF rather than waiting for confirmatory testing, especially in patients from endemic areas with fever and rash during the summer months.5

• Delay in initiating therapy may increase mortality, especially in children.7

• Adults (and children weighing >45 kg): doxycycline 100 mg bid for at least 7 days or 3 days after fever is gone.8

• Pregnancy: chloramphenicol 500 mg qid (or 50 mg/kg/day divided qid).

• Children: doxycycline 2.2 mg per kg IV/PO bid (maximum dose 200 mg daily).9

Complications

Multisystem illness may occur, including renal failure, pneumonitis, adult respiratory distress syndrome, myocarditis, hepatitis, gastrointestinal bleeding, diarrhea, skin necrosis, coagulopathy, hemolysis, encephalitis, and seizure.

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS

• Prevention. No vaccine exists and routine prophylaxis following tick exposure is not recommended as less than 1% of ticks in endemic areas are infected with Rickettsia.

• Patients reporting tick bites should inform their physician if they develop fever, headache, or rash within 14 days of exposure.

REFERENCES

1. CDC. Summary Notifiable Diseases United States June 30th, 2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2012;53:1–111.

2. Hopkins RS, Jajosky RA, Hall PA, et al. Summary of notifiable diseases—United States, 2003. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2005;52:1.

3. Abramson JS, Givner LB. Rocky Mountain spotted fever. Pediatr Infect Dis J 1999;18:539.

4. Ustaine RP. Dermatologic emergencies. Am Fam Physician 2010;82:773.

5. Thorner AR, Walker DH, Petri WA. Rocky Mountain spotted fever: state of the art clinical review. Clin Infect Dis 1998;27:1353.

6. Bratton RL, Corey GR. Tick-borne disease. Am Fam Physician 2005;71:2323.

7. Kirkland KB, Wilkinson WE, Sexton DJ. Therapeutic delay and mortality in cases of Rocky Mountain spotted fever. Clin Infect Dis 1995;20:1118.

8. Consequences of delayed diagnosis of Rocky Mountain spotted fever in children—West Virginia, Michigan, Tennessee, and Oklahoma, May–June 2000. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2000;49:885.

9. American Academy of Pediatrics. Rocky Mountain spotted fever. In: Pickering LK, ed. Red Book: 2012 Committee on infectious diseases. 29th ed. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2012

|

GENERAL PRINCIPLES

Definition

A parasite is an organism that lives on or in another living organism (the host) from which it derives nutrition. Medically important parasites include the single-celled protozoans, ectopods (e.g., lice and scabies), and helminths (roundworms or flatworms). Although commonly thought of as intestinal pathogens, parasites produce clinical syndromes as diverse as seizures and heart failure.

A few parasitic infections are common in primary care; these include infections caused by bed bugs, lice, Giardia, pinworms, scabies, and Trichomonas.. However, with an increasingly mobile population, doctors may also encounter less common parasitic diseases. The CDC’s Division of Parasitic Diseases and Malaria has identified five neglected parasitic diseases in the United States: Chagas disease, cysticercosis, toxocariasis, toxoplasmosis, and trichomoniasis. The Division’s Web site is an excellent resource for both providers and patients: www.cdc.gov/parasites.

Anatomy

During the course of their lifecycle, parasitic infections can involve multiple organs. Parasitic infection and symptomatology are listed here by organ system:

• Skin. Dermatitis (Ascaris, Capillaria hepatica, hookworms, Strongyloides, chigoe flea, cutaneous and visceral larva migrans, Dracunculus, lice, Mansonella, scabies, mites); migratory pruritic swellings (Loa loa); subcutaneous nodules, skin ulcers, and scars (cutaneous leishmaniasis, Dracunculus, Dirofilaria, Onchocerca, sparganum, Taenia, Trypanosoma brucei gambiense); swimmer’s itch (schistosomiasis); pruritus and skin depigmentation (onchoceriasis); temporal and periorbital swelling with conjunctivitis (acute Trypanosoma cruzi infection); facial and periorbital edema during acute infection (Trichinella); and ulcers (cutaneous and mucocutaneous leishmaniasis, T. gambiense, Dracunculus, Tungiasis)

• Central nervous system. Meningoencephalitis (African trypanosomiasis, Acanthamoeba, Angiostrongylus, Naegleria, cerebral malaria, schistosomiasis), new-onset seizures, or focal neurologic signs consistent with a space-occupying lesion (cysticercosis, malaria, toxoplasmosis, trichinosis, hydatid and coenurus cysts, Sparganosis)

• Eyes. Vitreous infestation (onchocercosis, ascariasis, ocular toxocariasis), conjunctivitis (Loa loa), keratoconjunctivitis and corneal ulcers (caused by free-living amebas), uveitis, choroiditis and choroidoretinitis (toxoplasmosis), anterior uveitis (Wuchereria bancrofti) periorbital swelling, and conjunctivitis (Trypanosoma cruzi)

• Hematologic. Microcytic anemia (malaria, Babesia, hookworm, Trichuris, trypanosomes), macrocytic anemia (fish tapeworms), leukopenia (malaria, visceral leishmaniasis), eosinophilia (invasive helminths, especially Schistosoma and Trichinella, Dientamoeba fragilis, and Cystoisospora belli)

• Lymphatic. Elephantiasis (lymphatic filariasis), lymphadenopathy (African trypanosomiasis, Mansonella ozzardi, toxoplasmosis, visceral leishmaniasis)

• Respiratory. Loeffler syndrome (Ascaris lumbricoides, Strongyloides), pneumonitis (hookworms, Pneumocystis, Strongyloides), chest pain and hemoptysis (paragonimiasis), pulmonary mass lesion (Dirofilaria, echinococcosis, paragonimiasis), tropical pulmonary eosinophilia (filariasis)

• Cardiovascular. Heart block, congestive heart failure (Trypanosoma cruzi)

• Intestinal. Appendicitis (Ascaris, Trichuris, pinworms); colic, diarrhea, and vomiting (Capillaria philippinensis, Cryptosporidium, intestinal flukes, Isospora belli, Strongyloides, Cyclospora, Giardia); mucoid and bloody diarrhea (amebiasis), bloody stool (schistosomiasis), obstruction (Ascaris, Hymenolepis nana, Taenia saginata); colitis (Trichuris); pruritus ani (Enterobius)

• Hepatobiliary. Liver abscess or cyst (Entamoeba histolytica, cysticercosis, hydatid disease), biliary obstruction (Ascaris lumbricoides), portal hypertension (schistosomes), hepatosplenomegaly (malaria, babesiosis, Capillaria hepatica, visceral leishmania, visceral larva migrans, Katayama fever in acute schistosomiasis)

• Genitourinary. Chyluria (lymphatic filariasis), hematuria (schistosomes), prostatitis, urethritis, and vaginitis (trichomonads)

• Musculoskeletal. Myositis (trichinosis, toxoplasmosis, Chagas disease), cysts (Echinococcus, cysticercosis)

Transmission

Transmission of parasites may occur via the fecal–oral route, through the skin, by blood transfusion or organ transplant, or by a suitable local vector such as a mosquito.

Epidemiology

• Populations at risk. International travelers (especially those traveling outside of industrialized countries and major cities), missionaries, and immigrants are at particular risk. Backpackers who drink untreated groundwater are at risk for acquiring Giardia, amebiasis, guinea worm, and Cryptosporidium as well as bacterial pathogens.

• Residents of institutions, including daycare centers, group homes, and nursing homes, are at risk for acquiring Giardia, amebiasis, as well as bacterial pathogens spread by fecal contamination. People who engage in oral–anal sex are at risk for acquiring E. histolytica and Giardia lamblia as well as viral pathogens such as hepatitis A virus, and bacteria such as Shigella.

• Risk by geographic area. For continuously-updated information about specific risks in various geographic regions, consult the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) web page (http://www.cdc.gov/travel/). The World Health Organization (WHO) also provides information for travelers (http://www.who.int/ith/en/).

• Immunosuppressed patients show increased susceptibility to some parasites. This group includes malnourished individuals, patients with cancer, patients on steroids, and patients with AIDS (discussed later in the chapter).

Screening and Prevention

• Routine testing for asymptomatic parasite carriage in travelers or food handlers is not recommended because of the low yield.

• Individuals with a high likelihood of exposure to parasites (missionaries, refugees, and immigrants arriving from endemic regions) can be treated empirically for intestinal helminths.1 Although not Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved for this indication, a single dose of albendazole (400 mg taken orally for both children and adults) may be superior to treating only those with positive ova and parasite examinations; testing is more expensive and results in fewer carriers receiving treatment.

• Individuals with suspected exposure to Giardia, amebiasis, or platyhelminths may need repeated stool examinations for ova and parasites (three is recommended) because of intermittent excretion. Giardia and amebiasis can also be diagnosed based on stool antigen tests.

Prevention Advice

• Travelers should avoid inhaling water mist while swimming, or swimming with open cuts or abrasions. They should not swim in freshwater areas where schistosomiasis is endemic (see http://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/yellowbook/2014/chapter-3-infectious-diseases-related-to-travel/schistosomiasis#4116).

• In areas where chlorinated or filtered tap water is not available, and hygiene and sanitation are poor, people should drink canned or bottled beverages, or beverages made with boiled water such as tea or coffee. Decontamination options include

• Boiling water for 1 minute at low altitudes, or for three minutes if above 6,500 feet. Water should be filtered through a cloth or allowed to settle prior to boiling.

• Disinfecting water can be done with chlorine bleach or iodine. Water should be filtered first. For each gallon, add 1/8 teaspoon (eight drops) of chlorine. Iodine dosing will depend upon formulation.

• Filters should be small enough to remove bacteria and Cryptosporidium.

• To prevent fecal–oral transmission of diseases, strict hand washing should be practiced.

• For mosquito-borne diseases, the best strategy is to avoid getting bitten. Travelers should use clothing that covers extremities and sleep under bed nets; ideally these items should be pretreated with Permethrin. DEET-containing repellants are probably the best agents for use on the skin. Mosquito activity is highest at dawn and dusk.

• Travelers should avoid foods that may harbor parasites, especially raw or undercooked foods. The general advice is: Boil it, Cook it, Peel it or Forget it! Salads and cut fruits are potentially a source of infections. Travelers should avoid consuming foods from street vendors, as well as unconventional foods or animal products.

• Infants under 6 months benefit from exclusive breastfeeding to prevent parasitic infections.

• Travelers should obtain prophylactic vaccines and medicines if traveling to endemic areas and consult with a travel clinic if they have any predisposing illnesses that increases their risks. The CDC maintains a list of travel clinics at http://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/page/find-clinic

DIAGNOSIS

History

The most important step in assessing risk is a careful history, including the patient’s social and physical environment (including past exposures to immigrants from endemic areas), travel history including duration of potential exposure, and personal habits. It is unnecessary to rule out parasitic infection in asymptomatic individuals who were never in environments where they might have been infected. Because parasitic infections can affect diverse systems, a thorough review of systems may be necessary to obtain the appropriate differential (see Clinical Presentations mentioned previously). If this history suggests a risk for parasitic disease, the clinician must then determine which parasites are potential pathogens.

• Parasites seen in stool. Roundworms or flatworm segments can be passed in stool. Specimens brought in by patients should be preserved in 70% alcohol and sent to a diagnostic laboratory. Objects such as earthworms or mucus plugs can be mistaken for parasites.

• HIV infection with certain parasites has been associated with either increased susceptibility or more severe diseases. The major parasitic infections include visceral leishmaniasis and those caused by Toxoplasma gondii, Cryptosporidium spp., Cyclospora spp., C. belli, Trypanosoma cruzi, Microsporum spp., Strongyloides stercoralis, and Plasmodium species.

Laboratory Studies

Diagnosis of Symptomatic Infection

• The CDC Division of Parasitic Diseases maintains an excellent Web site on the diagnostic evaluation of parasites (http://www.cdc.gov/dpdx/).

• Appropriate laboratory work should be obtained for symptomatic patients with risk factors for parasitic disease. In U.S. laboratories, only about 1% of ova and parasite tests indicate the presence of some form of parasite and most of these are nonpathogenic protozoans.

• Clinically useful diagnoses come almost exclusively from outpatients or hospitalized patients within the first 3 days of their admission. Testing asymptomatic patients is not recommended.

Office Examination

• Stool examination (ova and parasites). Three separate stool samples taken every other day increase the likelihood of finding pathogens. Examination of a fresh stool specimen permits visualization of short-lived motile forms that cannot be found in preserved or refrigerated specimens. Purged stools that are examined immediately are superior to preserved specimens, especially when one is looking for ameba; magnesium citrate can be used as a purgative. Ideally a thin, fresh slide of feces should be examined within an hour of collection, looking for trophozoites and amebas. Then, a drop of Gram iodine or Lugol solution is added to provide better visualization of cysts. Part of the sample should be placed in separate preservative containing vials according to supplied directions and sent to a reference laboratory. Care should be taken to avoid contamination with urine or water. Testing for Cryptosporidium and Cyclospora cysts requires special staining.

• The cellophane tape test is used to detect Enterobius (pinworm) and Taenia saginata eggs. Clear cellophane (Scotch) tape is placed with the sticky side down on the unwashed perianal area, preferably in the early morning before bathing or after defecation. The tape is placed (again sticky side down) on a microscope slide, which is examined for eggs. Adult pinworms can be seen with this technique. Sensitivity is improved by repeating the examination on subsequent days.

• Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendment (CLIA): Offices performing these tests should be CLIA-certified.

Clinical Laboratory Examination

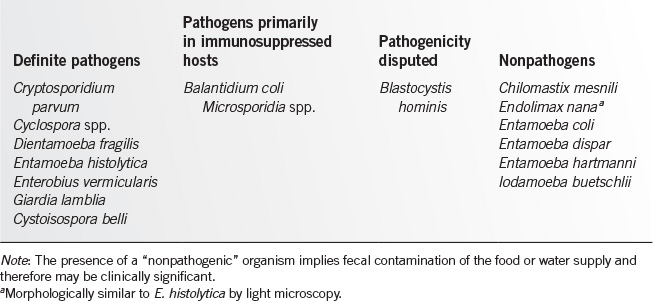

• Stool examination (ova and parasites). Various techniques exist for concentrating and staining stool specimens. When looking for helminth eggs, one or two concentrated preserved specimens are usually sufficient. Table 19.11-1 provides a guide to the interpretation of findings in the ova and parasite examination.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree