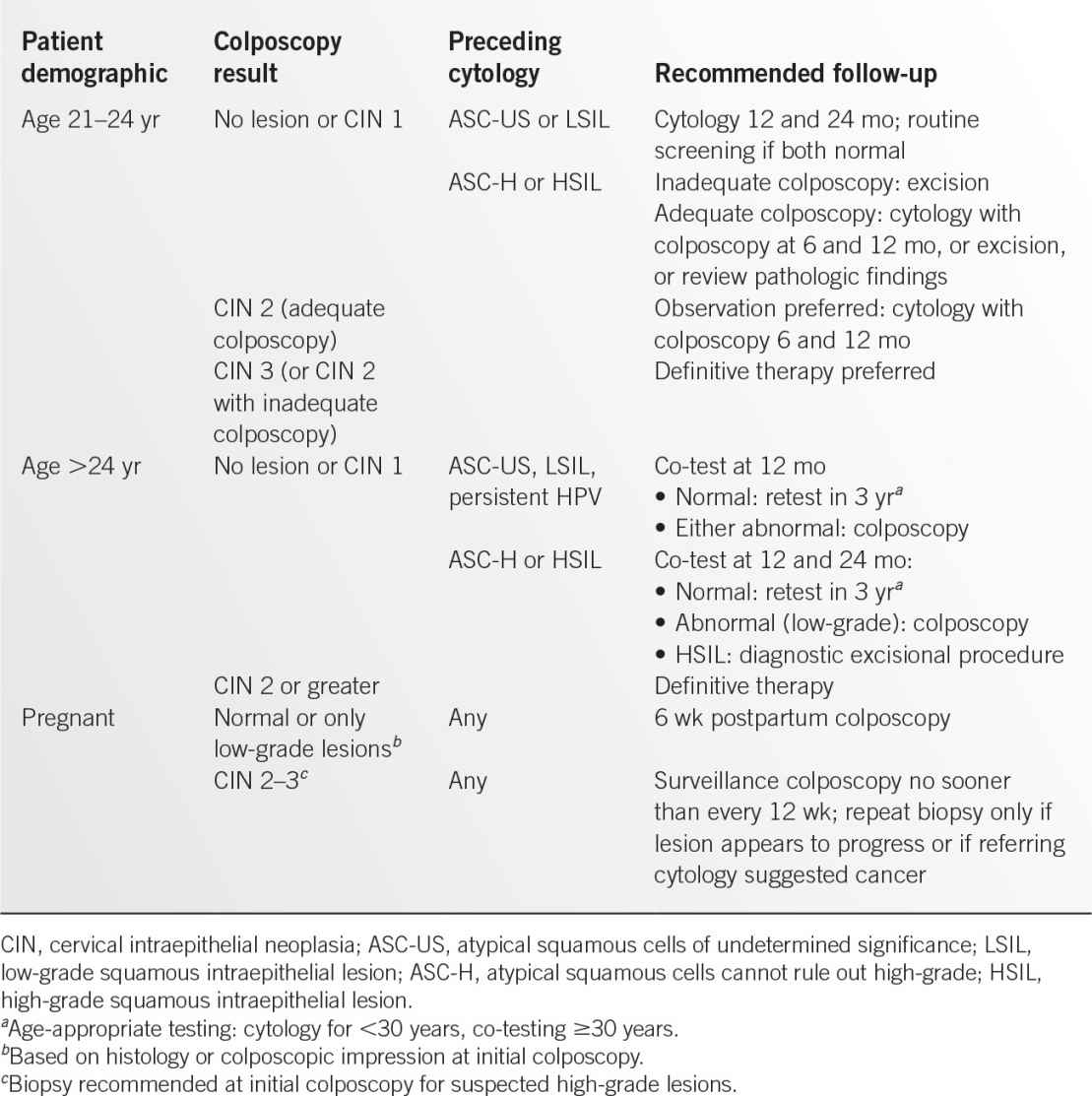

Figure 13.1-1. Vaginal smears of common vaginitis pathogens. A: Trichomonas vaginalis. B: Candida albicans. (A: Reproduced with permission from Sun T. Parasitic disorders: pathology, diagnosis, and management. 2nd ed. Baltimore, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1999; B: Reproduced with permission from Fleischer GR, Ludwig S. Baskin MN. Atlas of pediatric emergency medicine. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2004.)

• 7 to 14 days topical therapy.

• Oral fluconazole (100, 150, or 200 mg dose) every third day for total three doses.

AND

• One of the above initial doses plus oral fluconazole weekly for 6 months.

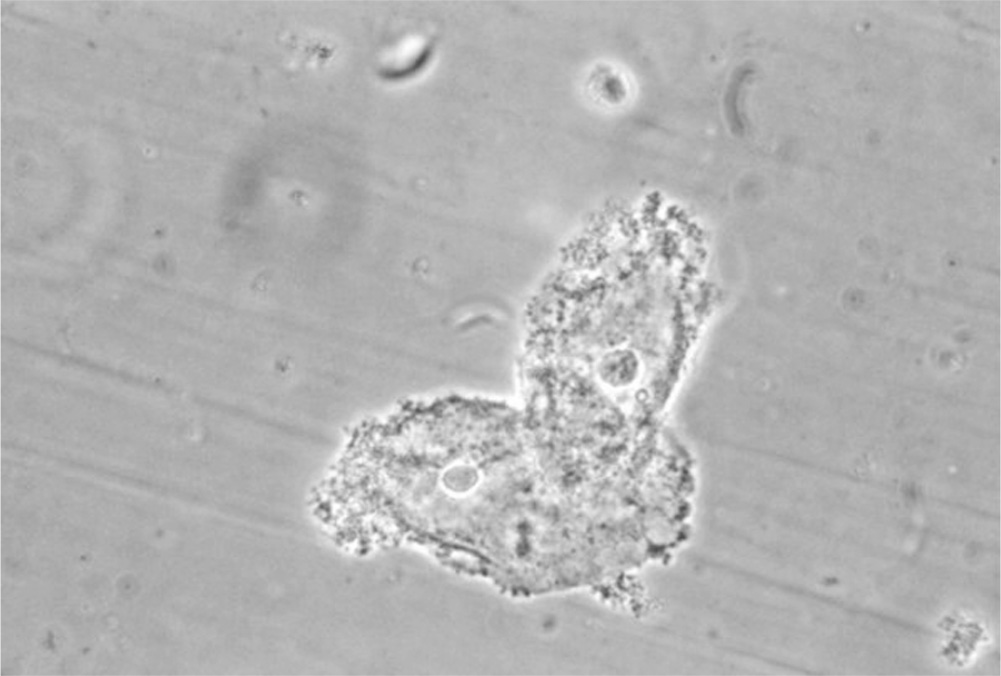

Figure 13.1-2. Clue cells. Clue cells are epithelial cells with clumps of bacteria clustered to their surface. These cells indicate the presence of bacterial vaginosis. (Courtesy M. Rein, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Public Health Image Library.)

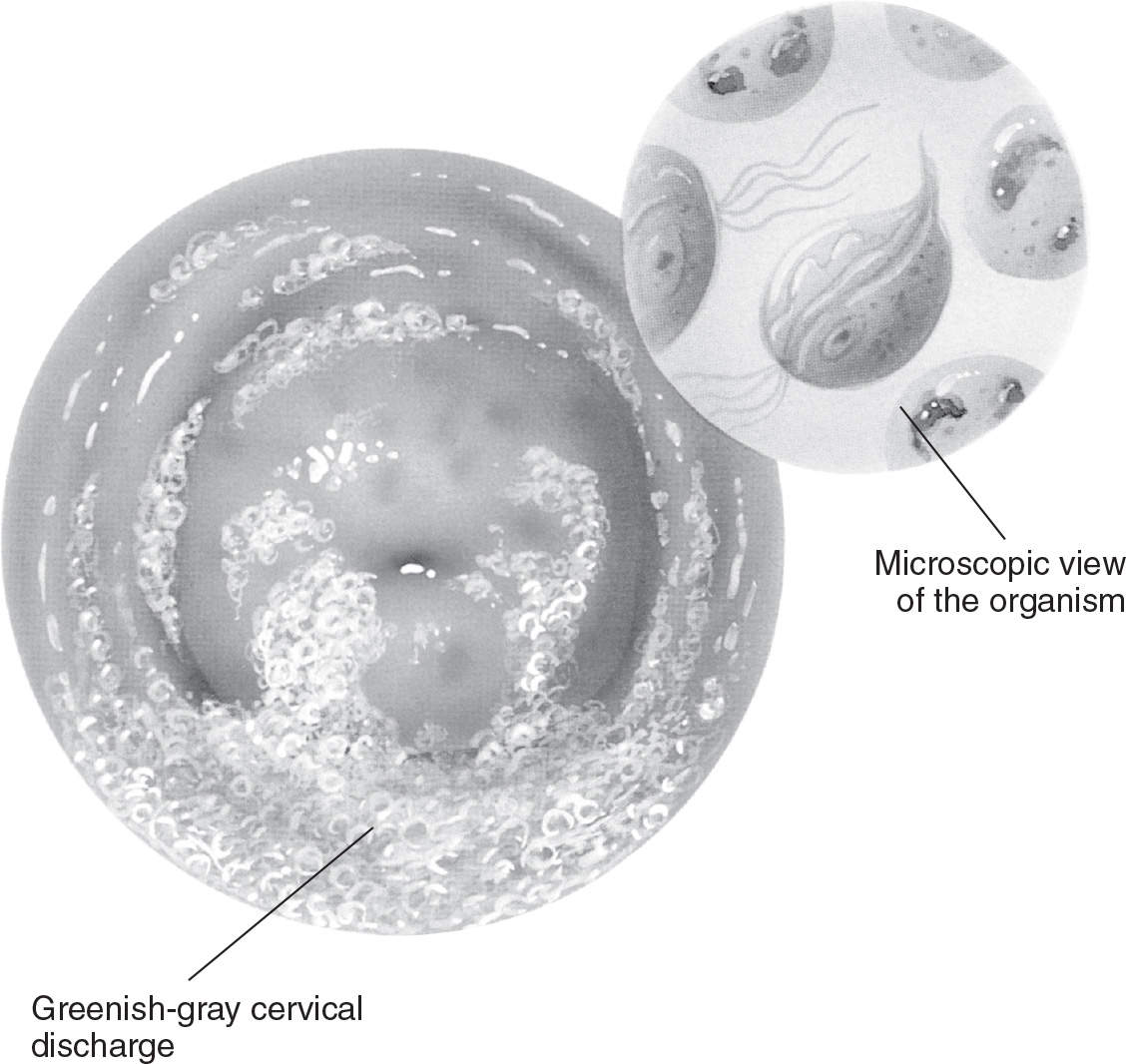

Figure 13.1-3. Trichomonal vaginitis. (From Anatomical Chart Company. Atlas of pathophysiology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2010:313.)

Trichomoniasis

Trichomoniasis is a protozoal infection caused by the organism Trichomonas vaginalis. In contrast to BV and Candida infection, trichomoniasis is a sexually transmitted infection.

Diagnosis

Clinical Presentation

Women with T. vaginalis infections typically have a profuse, yellow/green, frothy vaginal discharge with an unpleasant odor (see Figure 13.1-3). Vulvovaginal irritation can also be present. Examination of the cervix may reveal punctate hemorrhages on the cervix and vagina (“strawberry cervix”). Patients may complain of postcoital bleeding. Many of these infections are asymptomatic.6

Laboratory Studies

• Microscopic examination with the presence of mobile, flagellated trichomonads on wet mount (see Figure 13.1-1A).

• The vaginal pH is elevated (>4.5).

• Pap tests are specific but not sensitive for infections with Trichomonas. Infections based on Pap test results should be treated, but a normal Pap test does not rule out infection.7

• Cultures or nucleic acid amplification testing (NAAT) should be sent when there is a suspicion for Trichomonas infection despite a normal wet mount result due to high false negative rates for this test.

Treatment and Prevention of Recurrence

Standard treatment is a single oral dose of metronidazole, and topical therapy has been shown to be less effective. Patients should be counseled on a possible disulfiram reaction if alcohol is consumed concurrently. Patients should be counseled on prevention of future episodes through the use of male or female condoms.7

Medications

• A single 2-g dose of metronidazole.

• Tinidazole in a single oral 2-g dose is also likely as effective. Topical metronidazole has been shown to be less efficacious than oral metronidazole.

• Sexual partners should be treated as well. Resistant or recurrent infections may require a higher dose or longer duration of treatment with metronidazole (i.e., 500-mg orally twice daily for 7 days); no other medication is currently available in the United States to treat trichomoniasis. Patients with an allergy to metronidazole should undergo desensitization treatment.

Atrophic Vaginitis

Atrophic vaginitis is caused by estrogen deficiency and usually occurs in postmenopausal women.1

Diagnosis

Clinical Presentation

Like other forms of vaginitis, atrophic vaginitis is often asymptomatic. Symptoms include vaginal soreness, burning, dyspareunia, and occasionally bleeding or spotting.

Physical Examination

The vaginal mucosa is thin, friable, and pale or erythematous if inflammation is present. It can appear dry, or patients may have a thin, watery discharge.

Laboratory Studies

• Vaginal pH is increased (5 to 7).

• Wet mount reveals parabasal cells (small, round epithelial cells with large nuclei) and polymorphonuclear leukocytes if inflammation is present.

Treatment

Patients can be reassured that mild symptoms are normal and do not require treatment. Dryness can be treated with vaginal lubricants. Topical or oral estrogen replacement is used to treat more bothersome symptoms of atrophic vaginitis, though patients should be counseled on long-term risks of endometrial carcinoma, particularly with higher doses of estrogen. Consider use of oral progesterone along with estrogen for long-term treatment.1

CERVICITIS

General Principles

Definition

Cervicitis refers to inflammation of the uterine cervix and is characterized by a purulent cervical discharge or a friable cervix on examination. White blood cells on wet mount or Gram stain are also common, although there is no standard number of white blood cells that confirms the diagnosis.8

Epidemiology

Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhea are the most common identified causes of cervicitis; however, these infections may account for only 20% to 50% of women with cervicitis.5 Other common causes of cervicitis include infectious causes (Mycoplasma, Ureaplasma, bacterial vaginosis, herpes simplex, cytomegalovirus, Trichomonas, and adenovirus) and nonspecific inflammation.9 In some women, a cause will not be identified after diagnostic evaluation.8

Diagnosis

History

Vaginal discharge, postcoital bleeding, dyspareunia, and irregular vaginal bleeding are common symptoms of cervicitis. Many women are asymptomatic, and cervicitis may be found on an examination done for other reasons, such as Pap smear collection.3

Physical Examination

Physical examination commonly reveals mucopurulent discharge, cervical ectropion, and a friable cervix that continues to bleed after passage of a cotton swab through the cervical os. Women with cervicitis should also be examined for cervical motion tenderness, as this can indicate the presence of pelvic inflammatory disease.

Laboratory and Imaging

Women who present with cervicitis should initially be tested for gonorrhea, Chlamydia, BV, and Trichomonas. Testing for Chlamydia and gonorrhea is done with a NAAT and can be performed on urine, vaginal, or cervical samples. The diagnosis of BV is made by Amsel’s criteria (see Bacterial Vaginosis section). Trichomonal infection can be diagnosed on wet mount or through NAAT or culture.8

Differential Diagnosis

In addition to infectious causes, clinicians should consider the possibility of chemical irritants or cervical malignancy.8

Treatment

Medications

High-risk women, including younger women who are at risk due to their age, should receive empiric treatment for gonorrheal and chlamydial infections. When Trichomonas or BV is diagnosed in a woman with cervicitis, she should be treated. Empiric antibiotic treatment is not recommended for women who are at low risk or who have negative test results for specific infections.8 Please see the chapters on Chlamydia and Gonorrhea for more details about the treatment of these infections.

Patient Education

Gonorrhea, Chlamydia, and Trichomonas infections are spread by intercourse with an infected partner.3 Male and female condoms reduce the risk of transmission. It is important to recognize that a diagnosis of a sexually transmitted disease can be very stressful for a patient and her partner.

REFERENCES

1. Hainer B, Gibson M. Vaginitis: diagnosis and treatment. Am Fam Physician 2011;83:807–815.

2. Amsel R, Totten PA, Spiegel CA, et al. Nonspecific vaginitis: diagnostic criteria and microbial and epidemiologic associations. Am J Med 1983;74:14–22.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted disease treatment guidelines. MMWR 2010;59(No. RR-12):1–110.

4. Tibaldi C, Cappello N, Latino MA, et al. Vaginal and endocervical microorganisms in symptomatic and asymptomatic non-pregnant females: risk factors and rates of occurrence. Clin Microbiol Infect 2009;15:670–679.

5. Pappas PG, Kauffman CA, Andes D, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of candidiasis: 2009 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clinical Infect Dis 2009;48(5):503–535.

6. Bachmann LH, Hobbs MM, Seña AC, et al. Trichomonas vaginalis genital infections: progress and challenges. Clinical Infect Dis 2011;53(Suppl 3):S160–S172.

7. Gülmezoglu AM, Azhar M. Interventions for treating trichomoniasis in women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011;(5):CD000220. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000220.pub2.

8. Taylor SN, Lensing, S, Schwebke J, et al. Prevalence and treatment outcome of cervicitis of unknown etiology. Sex Transm Dis 2013;40:379–385.

9. Patel MA, Nyirjesy P. Role of mycoplasma and ureaplasma species in female lower genital tract infections. Curr Infect Dis Rep 2010;12:417–422.

| Dysmenorrhea and Premenstrual Syndrome |

DYSMENORRHEA

General Principles

Definition/Pathophysiology

Dysmenorrhea is cramping pain associated with menstruation. Primary (functional) dysmenorrhea is a painful paroxysmal syndrome that precedes or may accompany menses. It is not associated with pelvic pathology. Secondary dysmenorrhea is painful menses caused by pelvic disease. The pain is thought to be due to elevated levels of prostaglandin F2α. Prior to the onset of menses, cyclic progesterone withdrawal leads to the degradation of endometrial cell membranes. The cellular debris is converted to arachidonic acid, which is further metabolized by cyclo-oxygenase (COX) enzymes to form prostaglandins.1 The prostaglandins stimulate endometrial and uterine smooth muscle contractility and promote myometrial vasoconstriction. Ischemia develops, causing an angina equivalent in the uterus and results in pain. Other studies have also shown elevated leukotriene levels to be a contributing factor. Vasopressin was thought to be an aggravating agent, but vasopressin antagonists have shown no effect on the relief of menstrual pain.2

Epidemiology/Etiology

Primary dysmenorrhea is one of the most common gynecologic complaints, thought to affect from 50% to 90% of women of reproductive age. It is a leading cause of absenteeism for women under 30 years of age and the leading cause of school absences for adolescent women.3 Secondary (acquired) dysmenorrhea is pain that results from a pelvic abnormality. Endometriosis is the most common cause of secondary dysmenorrhea.4 Other possible etiologies include reproductive tract structural anomalies, adenomyosis, uterine tumors and leiomyomata, polyps, chronic salpingitis, pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), intrauterine device (IUD) use, cervical stenosis, irritable and inflammatory bowel syndromes, and urologic disorders. Several authors have correlated dysmenorrhea with smoking cigarettes, high intake of omega-6 fatty acids, nulliparity, depression, and stress. Causation has yet to be proved in rigorous controlled studies.

Diagnosis

Clinical Presentation

Primary dysmenorrhea usually appears within 12 months after menarche. It is characterized by symptom onset around the time of menses. Pain can be colicky or spasmodic and is usually felt in the lower abdomen, back, and thighs. Patients may also experience nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, headache, fatigue, and dizziness—prostaglandin-mediated symptoms. Menstrual flow may be heavier than normal. Symptoms are often worst on the first day of menses and then gradually resolves. Physical examination will be unrevealing. A pelvic examination is not initially required to make the diagnosis, especially in nonsexually active and virginal women. The diagnosis can generally be made on the basis of history alone. If an adolescent is sexually active, a pelvic examination should be performed due to the high risk of PID in this population.4 If the history and physical examination are inconsistent, or initial therapies are unsuccessful, further evaluation for secondary causes of dysmenorrhea should be pursued.

In secondary dysmenorrhea, onset is typically more than 2 years after menarche. Pain is not limited to the menstrual cycle. Pelvic and rectovaginal examinations should be performed if endometriosis is suspected. Physical examination may reveal adnexal masses, fixed uterus or reduced uterine mobility, and uterosacral nodularity in patients with endometriosis; mucopurulent cervical discharge in those with PID; and uterine asymmetry or enlargement in those with adenomyosis.4

Treatment

First-line therapy is either a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID; e.g., naproxen, ibuprofen, mefenamic acid-nonspecific COX inhibitors) or a specific COX-2 inhibitor (e.g., celecoxib). These medications act to decrease prostaglandin production, thereby decreasing both menstrual flow and prostaglandin-mediated pain. Medications should be taken 1 to 2 days before the onset of menses and continued on a fixed regimen for about 3 days.4 Because of the recent concerns about the safety of COX-2 inhibitors, the short duration of therapy for relieving primary dysmenorrhea, and the low cost of NSAIDs, it is prudent to recommend established NSAIDs with better long-term safety data as the preferred treatment.5 Topical heat has been shown to be more effective than placebo and may be as effective as NSAIDs in small studies.4 Other pharmacologic therapies for dysmenorrhea have included oral contraceptives (either traditional or extended cycle dosing), leuprolide, danazol, depot medroxyprogesterone, levonorgestrel-containing IUD, nifedipine, terbutaline, oral guaifenesin,6 magnesium, thiamine, aspirin, B12, vitamin E, fish oil supplements, and the Japanese herb Toki-shakayaku-san.5

Nontraditional modalities include acupuncture and acupressure, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) unit therapy, and local application of unidirectional static magnets; however, there is limited and inconsistent evidence on their effectiveness.7 Surgery is considered the intervention of last resort. Surgical interventions include laparoscopic uterosacral nerve ablation, presacral neurectomy, and hysterectomy. The first-line treatment for dysmenorrhea caused by endometriosis is combined oral contraceptives.4 Treatment for secondary dysmenorrhea is directed to the specific underlying cause and referral to the appropriate specialist for further medical or surgical treatment should be made.5

Despite the great prevalence of dysmenorrhea, many patients will not report symptomatology unless the provider specifically inquires. Some chronic complications with inadequately treated primary dysmenorrhea include anxiety and depression. Infertility can become a complication with certain causes of secondary dysmenorrhea. Inquiry and intervention can result in significant improvement of quality of life for these women.

PREMENSTRUAL SYNDROME

General Principles

Definition

Premenstrual syndrome (PMS) is a poorly understood psychoendocrine condition characterized by an array of somatic, cognitive, affective, and behavioral disturbances that recur in cyclic fashion during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle and resolve with the onset of menstruation. More than 150 symptoms have been documented, varying from mild to severe enough to disrupt normal activities and interpersonal relationships. Not all cycles are associated with PMS symptoms and not all premenstrual changes should be labeled PMS.

Pathophysiology/Etiology

PMS represents a biophysiologic, endocrine phenomenon. Altered levels of various hormones have been offered as the cause for premenstrual symptomatology, including estrogen, progesterone, prolactin, growth hormone, thyroid hormone, follicle-stimulating hormone, luteinizing hormone, antidiuretic hormone, insulin, prostaglandin, and cortisol. Studies have failed to confirm any of these as absolutely causative.8 However, women with PMSs are thought to have an altered response to normal gonadal steroids during the luteal phase and their effect on neurotransmitters such as serotonin and GABA in the CNS.9 Premenstrual symptomatology and behavior may also stem from social, psychologic, or cognitive dysfunction.

Diagnosis

Clinical Presentation

There is no typical presentation of PMS. Some of the more common physical symptoms include abdominal bloating and cramping, breast tenderness, fluid retention and weight gain, acne, cold sores, fatigue, and head and muscle aches. Emotional changes include anxiety, panic, depression, heightened aggressiveness, hostility, food craving, forgetfulness, insomnia, irritability, mood lability, poor concentration, tearfulness, and reduced coping skills. In 2000, the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology (ACOG) published a practice bulletin of 10 PMS diagnostic criteria. According to ACOG, the diagnosis of PMS requires that a woman has one or more of the affective or somatic symptoms listed. Symptoms must occur during the 5 days before menses (late luteal phase) in each of the three prior menstrual cycles; be relieved within 4 days of the onset of menses; and not recur until at least cycle day 13. The symptoms must be bothersome to the patient. They must exist in the absence of any pharmacologic therapy, hormones, alcohol, or recreational drugs. Finally, all other psychiatric or medical disorders must be excluded.10 The American Psychological Association (APA) included severe PMS in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 5th edition (DSM-5) as an axis I diagnosis called premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD). The DSM-5 defines PMDD as a severe form of PMS in which symptoms of anger, irritability, and internal tension are prominent.11 A woman must experience five or more from a list of 11 symptoms to fit PMDD criteria. As with the diagnosis of PMS, the symptoms must be experienced only in the luteal phase; all other diagnoses must be excluded; and the patient must have experienced them for the majority of cycles within the past year.10

History/Physical/Laboratory

A detailed history must be obtained, including menstrual history and inquiries about alcohol, tobacco, and recreational drugs. A complete physical examination must be performed. The need for in-depth neurologic or psychologic evaluation may become apparent. No specific diagnostic test is available for detecting PMS/PMDD. Laboratory investigation should be tailored to the individual patient. For example, complete blood count and thyroid studies should be considered in patients with menorrhagia or chronic fatigue. Charting the menstrual cycle and documenting symptomatology must be done for two to three cycles. Patients write down the symptoms that trouble them most and rate the severity throughout the entire menstrual cycle. The Daily Record of Severity of Problems (DRSP) form, a self-administered questionnaire, is the most commonly used tool.11 Presence of luteal phase symptoms in at least two cycles, lack of follicular phase symptoms, and absence of other specific disease entities strongly suggest the diagnosis of PMS or PMDD.

Treatment

Nonpharmacologic

The clinician must individualize the treatment plan to maximize therapeutic response. Treatment should begin with a 2- to 3-month trial of lifestyle changes while the patient records symptoms. This is recommended in women with mild PMS that do not cause distress or socioeconomic dysfunction.12 Stress management strategies should be taught. Sufficient rest should be advocated. Regular aerobic exercise has been demonstrated to alleviate some PMS symptomatology, probably due to endogenous endorphin release. A well-balanced diet with adequate protein, fiber, and complex carbohydrates is essential for everyone’s good health. However, these recommendations have not been investigated in rigorous controlled studies. Caffeine, salt, excess sugar, tobacco, alcohol, and recreational drugs may worsen physical symptoms and emotional lability. Multivitamins, calcium, and magnesium supplements may be helpful. Pyridoxine (vitamin B6) may reduce fatigue, depression, and irritability in selected women. However, there is no convincing evidence that any of these are more effective than placebo and carry a potential for harm such as peripheral neuropathy with high-dose B6.12

Pharmacologic

If premenstrual complaints do not respond to the above and the presence of psychological disorders, substance abuse or hypothyroidism has been considered, medical therapy can be initiated. Symptom logs assist the clinician in tailoring treatment to individual needs. Prostaglandin inhibitors can relieve headaches, body aches, and dysmenorrhea. Spironolactone 25 to 50 mg bid during cycle days 14 to 28 may reduce fluid retention. Danazol and bromocriptine have been utilized in the past to reduce mastalgia. However, adverse side effects limit their usefulness.

Without menstrual cyclicity, PMS cannot occur. Oral contraceptives, depomedroxyprogesterone, levonorgestrel-containing IUDs, and gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists have been tried with variable success. Oral contraceptive pills (OCPs) that contain the progestin drospirenone (an anti-mineralocorticoid and anti-androgen) are effective in reducing bloating and mood changes that accompany the placebo pill week. In 2012, the FDA stated the OCP-containing drospirenone may be associated with a higher risk of venous thromboembolism compared with levonorgestrel and other progestins.12 The recommendation is to assess each individual’s risk of Venous thromboembolism (VTE) prior to starting this medication in a new user. Multiple herbs have been utilized with variable success and safety in treating premenstrual symptoms. These include evening primrose oil, black current oil, chaste tree extract, black cohosh, wild yam root, dong quai, kava kava, and St. John’s wort. Interactions with other medications the patient might be taking must always be considered.13

Selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are the first-line drugs for treating PMDD. Sertraline or fluoxetine are typically used first.12 They can be administered daily or only during the luteal phase (starting on cycle day 14). Treatment only during the luteal phase has fewer adverse side effects and is less expensive; however, it is important to ensure the patient is asymptomatic during the follicular phase or else she will be undertreated.12 If SSRIs are ineffective or patient still has residual symptoms despite SSRI therapy, one option is to augment treatment with low-dose alprazolam.12 Alprazolam is an anxiolytic with proven effectiveness for symptoms of premenstrual tension, anxiety, irritability, and hostility. However, its addictive potential makes it a second-line treatment. Buspirone is an effective anxiolytic that is not addictive.

PMS is a complex disorder of reproductive-aged women. Successful management requires continued communication and collaboration between patient and clinician.

REFERENCES

1. Harel Z. Cyclooxygenase-2 specific inhibitors in the treatment of dysmenorrhea. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 2004;17:75–79.

2. Shushan A. Complications of menstruation and abnormal uterine bleeding. In: DeCherney A, Nathan L, Goodwin TM, et al., eds. Current diagnosis & treatment: obstetrics & gynecology. 11th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:61–619.

3. Sultan C, Gaspari L, Paris F. Adolescent dysmenorrhea. In: Sultan C, ed. Pediatric and adolescent gynecology. Evidence-based clinical practice. 2nd ed. Basel: Karger; 2012:171–180.

4. Osayande A, Mehulic S. Diagnosis and initial management of dysmenorrhea. Am Fam Physician 2014;89:341–346.

5. Danakas G, Alvero R. Dysmenorrhea. In: Ferri FF, ed. Ferri’s clinical advisor 2014. Philadelphia, PA: Mosby; 2014:352.

6. Marsden JS, Strickland CD, Clements TL. Guaifenesin as a treatment for primary dysmenorrhea. J Am Board Fam Pract 2004;17:240–246.

7. Eccles NK. A randomized double-blinded, placebo-controlled pilot study to investigate the effectiveness of a static magnet to relieve dysmenorrhea. J Altern Complement Med 2005;11:681–687.

8. Winer SA, Rapkin AJ. Premenstrual disorders: prevalence, etiology and impact. J Reprod Med 2006;51:339–347.

9. Rapkin AJ, Akopians AL. Premenstrual Syndrome. https://www.clinicalkey.com/. Updated January 7, 2014. Accessed January 16, 2014.

10. Futterman LA, Rapkin AJ. Diagnosis of premenstrual disorders. J Reprod Med 2006;51:349–358.

11. Yonkers KA, Casper RF. Clinical manifestations and diagnosis of premenstrual syndrome and premenstrual dysphoric disorder. UpToDate. www.uptodate.com/home/index.html. Updated November 8, 2013. Accessed January 16, 2014.

12. Kasper RF, Yonkers, KA. Treatment of premenstrual syndrome and premenstrual dysphoric disorder. UpToDate. www.uptodate.com/home/index.html. Updated March 17, 2014. Accessed March 28, 2014.

13. Kaur G, Gonsalves L, Thacker HL. Premenstrual dysphoric disorder: a review for the treating practitioner. Cleve Clin J Med 2004;71:303–321.

| Abnormal Genital Bleeding in Women and Girls |

GENERAL PRINCIPLES

Definition

Abnormal genital bleeding is any blood loss from the vaginal or perineal area other than the individual menstrual pattern of flow of a premenopausal girl or woman, or the expected cyclic hormonal bleeding in a postmenopausal woman taking hormones.

Terminology

A revised terminology system for abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB) in non–gravida-reproducing women was introduced in 2011 by the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics. Within this system, the etiologies of the symptoms of AUB are classified as “related to uterine structural abnormalities” and “unrelated to uterine structural abnormalities” and categorized by the acronym PALM-COEIN (polyp, adenomyosis, leiomyoma, malignancy and hyperplasia, coagulopathy, ovulatory dysfunction, endometrial, iatrogenic, and not yet classified).1

Anatomy

Bleeding coming from structures surrounding the vagina, rectum, and perineum must be differentiated from uterine bleeding originating from the cervical os. Pregnancy, structural pelvic pathology such as fibroids or polyps, benign and malignant tumors, anovulation, and coagulopathies are the leading causes.

Epidemiology

The incidence of genital bleeding from all causes is unclear, but AUB accounts for nearly one-third of all gynecologic visits, mostly at menarche or perimenopause. In postmenopausal women, an estimate of uterine bleeding in the first 12 months is 409 per 1,000 person-years, but only 42 per 1,000 person-years 3 years postmenopause.

Classification

• Nonuterine. The actual source of the bleeding may not be obvious. A laceration of the cervix, or of the vagina, especially if high in a fornix, may appear to be uterine bleeding. Urinary, rectal, or vulvar bleeding may be mistaken for vaginal bleeding.

• Vulvar or vaginal: infection, laceration, tumor, foreign body

• Extravaginal: perineal, urinary, rectal

• Systemic/medical: bleeding diathesis, thrombocytopenia; von Willebrand disease; liver, renal, endocrine disease

• Uterine. Age-grouping is important.

• Age: premenarche—any bleeding is abnormal

• Age: 13 to 40

![]() The clinician should consider pregnancy-related causes, especially ectopic pregnancy, even when bleeding is light or moderate, and even in young and perimenopausal women. Once pregnancy is ruled out, the diagnosis of dysfunctional uterine bleeding (DUB), although one of exclusion, does not require total certainty before reasonable treatment for anovulation is implemented.

The clinician should consider pregnancy-related causes, especially ectopic pregnancy, even when bleeding is light or moderate, and even in young and perimenopausal women. Once pregnancy is ruled out, the diagnosis of dysfunctional uterine bleeding (DUB), although one of exclusion, does not require total certainty before reasonable treatment for anovulation is implemented.

![]() Anovulatory bleeding (DUB) is common and may be treated as such without an exhaustive search for all other causes initially, as long as there is a normal medical history, pregnancy test, complete blood count (CBC), Pap smear when appropriate and a normal bimanual pelvic examination. Although not all uterine bleeding in this group will prove to be DUB, serious pathology in the face of normal findings is unlikely. If hormonal manipulation fails, a more complete workup can follow. Over age 35, an endometrial biopsy should be done.2

Anovulatory bleeding (DUB) is common and may be treated as such without an exhaustive search for all other causes initially, as long as there is a normal medical history, pregnancy test, complete blood count (CBC), Pap smear when appropriate and a normal bimanual pelvic examination. Although not all uterine bleeding in this group will prove to be DUB, serious pathology in the face of normal findings is unlikely. If hormonal manipulation fails, a more complete workup can follow. Over age 35, an endometrial biopsy should be done.2

• Age: 40 and older—higher index of suspicion of neoplasm. A very different scenario pertains to the peri- and postmenopausal woman, in whom bleeding must be investigated before anovulation can be assumed.

• Age: Postmenopausal—neoplasm until proven otherwise, unless known hormonal cause.

Etiology

• Pregnancy should be considered.

• Anovulation is a common cause (DUB, defined as uterine bleeding associated with anovulation, in the absence of other pathology):

• Physiologic: Adolescence (although 4% to 20% of adolescents have a coagulopathy underlying their abnormal bleeding), perimenopause (although abnormal bleeding must be considered neoplastic or hyperplastic until proven otherwise), lactation, and pregnancy.

• Pathologic: Hyperandrogenic anovulation (e.g., polycystic ovary syndrome, congenital adrenal hyperplasia, androgen-producing tumors), hypothalamic dysfunction (e.g., secondary to anorexia nervosa), hyperprolactinemia, hypothyroidism, primary pituitary disease, premature ovarian failure, and iatrogenic factors (e.g., secondary to radiation therapy or chemotherapy).

• Iatrogenic or treatment-induced:

![]() Estrogen withdrawal occurs after removal or irradiation of ovaries, or after giving and then withdrawing estrogen to a person without ovaries. (Midcycle bleeding can be due to preovulation drop in estrogen.)

Estrogen withdrawal occurs after removal or irradiation of ovaries, or after giving and then withdrawing estrogen to a person without ovaries. (Midcycle bleeding can be due to preovulation drop in estrogen.)

![]() Estrogen breakthrough is due to stimulation of endometrium from unopposed low- or high-level estrogen. (Low-dose estrogen produces intermittent light spotting; high-dose estrogen yields amenorrhea followed by profuse bleeding. Cyclic progesterone corrects this.)

Estrogen breakthrough is due to stimulation of endometrium from unopposed low- or high-level estrogen. (Low-dose estrogen produces intermittent light spotting; high-dose estrogen yields amenorrhea followed by profuse bleeding. Cyclic progesterone corrects this.)

![]() Progestin withdrawal occurs only if there has been prior estrogen priming.

Progestin withdrawal occurs only if there has been prior estrogen priming.

![]() Progestin breakthrough can occur when endometrium becomes so atrophic that lack of estrogen effect yields too little and too ragged a lining for synchronous cellular events. (Estrogen replacement therapy can restore responsiveness. This occurs after months on oral contraceptives (OCs) or depoprogesterone. Adding estrogen for a week usually corrects the problem.)

Progestin breakthrough can occur when endometrium becomes so atrophic that lack of estrogen effect yields too little and too ragged a lining for synchronous cellular events. (Estrogen replacement therapy can restore responsiveness. This occurs after months on oral contraceptives (OCs) or depoprogesterone. Adding estrogen for a week usually corrects the problem.)

• Noncyclic uterine bleeding (non-DUB)

• Uterine leiomyoma, leiomyosarcoma, endometrial polyp(s)

• Endometrial hyperplasia or carcinoma

• Cervical or vaginal neoplasia

• Endometritis, adenomyosis

• Bleeding associated with pregnancy (threatened or incomplete abortion, trophoblastic disease, ectopic pregnancy)

• Bleeding associated with the puerperium (retained products of conception, placental polyps, subinvolution of the uterus)

• Coagulopathies (von Willebrand disease, platelet abnormalities, thrombocytopenic purpura)

• Iatrogenic causes, medications, and devices—intrauterine devices (IUDs), diaphragms, pessaries

• Systemic diseases (liver, renal, thyroid, other endocrine)

• Infection, laceration or contusion, tumor, foreign body

• Perineal, rectal, urinary disease

• Systemic medical causes include bleeding diatheses, especially thrombocytopenia; von Willebrand disease; and liver, renal, endocrine disease

• Ovulatory excessive bleeding2

DIAGNOSIS/TREATMENT

Clinical Presentation

Abnormal genital bleeding can range from urgent or emergent bleeding to mild irregular bleeding in between menstrual cycle. Most common cause is pregnancy or its complications.

Assessment/History

When taking a detailed history, several questions must be answered, including pregnancy status, reproductive status, and the source of bleeding. This will help determine differential diagnosis and disposition of the patient. History should include relevant medical history, menstrual history, sexual history, contraceptive history, family history of bleeding disorders and thyroid diseases, and risk factors for endometrial cancer.

Severity

• Rate of flow. How heavy is the bleeding? Pad counts are unreliable because of differences of absorbency but may give a rough estimate. The patient’s own opinion is probably more valid. When did it start? Is the blood bright red or dark, with or without clots? If it is heavier than she has ever seen it, if it is flowing, if brighter red than menstrual blood, and if there are clots or pieces of tissue, there might be significant hemorrhage and the patient should not wait even a short time. If she cannot get to the office immediately, she should go to the nearest emergency room, by ambulance or 911. She should be instructed to retrieve any tissue passed for the purpose of analysis.

• Amount of flow. A rough estimate of blood loss can be made by asking how much more bleeding than a usual period she has had since onset. (Normal menstrual blood loss is 20 to 80 cc.)2

Associated Symptoms

Has there been fever, dizziness, abdominal pain, and diarrhea? Any of these could signal associated pelvic infection or abscess, shock, severe loss of blood volume, dehydration, other intra-abdominal pathologic process, or bleeding tendency.

Physical Examination

Check vital signs; do abdominal, perineal, vaginal, pelvic, and rectal examination. The examination must meticulously pinpoint the exact source, which may not be obvious. A physical examination with good exposure for the speculum examination, and optimal palpation of pelvic organs using bimanual and rectovaginal techniques, is crucial to finding serious and treatable pathology. Obesity and hirsutism should be noted. An estimate of prior hormonal influences should be made in an attempt to classify the type of anovulation.2

Basic Laboratory Tests

Initial tests should include pregnancy test (β-human chorionic gonadotropin) and CBC with platelets and differential. Additional testing based on history and physical examination may include endocrine, thyroid function tests, prolactin level, androgen level, follicle-stimulating hormone/luteinizing hormone, estrogen levels, and coagulation studies.2,3

Examination Findings

Examination findings may suggest other studies, such as endometrial biopsy or colposcopy, hysteroscopy, pelvic and/or endovaginal sonography (transvaginal scan [TVS]), hysterosalpingography, and saline infusion hysterosonography (saline infusion sonography [SIS]), usually performed by radiologists or gynecologists. Most procedures carry known risks, benefits, and advantages, and are chosen based on individual needs of the specific patient and circumstance.

Ultrasonography

Pelvic ultrasound is the first-line imaging study in women with AUB. Transvaginal examination should be performed, unless there is a reason not to do a vaginal examination. Ultrasound is effective at characterizing uterine and adnexal lesions. If it is performed in a postmenopausal woman, an endometrial biopsy is mandatory when the endometrial thickness is greater than 4 mm. In premenopausal women, endometrial findings on ultrasound is not a useful test since major variation during normal menstrual cycle.4

Endometrial Biopsy

After pregnancy has been excluded, endometrial biopsy should be performed to exclude endometrial neoplasia or endometritis. Endometrial biopsy should be performed in all women age 45 years or older with AUB, women below age 45 years with persistent AUB who failed medical management, those with a history of unopposed estrogen exposure, or those at high risk for endometrial cancers.3

Management

Treatment for specific pathology depends on the underlying cause and may be managed by the family doctor or may require referral to a gynecologist, endocrinologist, or gynecologic oncologist. Acute, heavy bleeding requires close observation, accurate determination of the source and likely cause, and immediate therapy. Hospitalization, hydration, and transfusion may be required.

Medical Management

In the hemodynamically unstable patient, fluid resuscitation and blood replacement are the first priority. Therapeutic options are intravenous high-dose estrogen, intrauterine tamponade, uterine curettage, uterine artery embolization, and hysterectomy. High-dose intravenous estrogen (Permarin) 25 mg is given every 4 to 6 hours for 24 hours. If bleeding does not subside after 8 hours, other treatments should be used.5 Antiemetics should be given for nausea.

In patients that are hemodynamically stable with severe uterine bleeding patient, first-line therapy is high-dose oral estrogen (Premarin) 2.5 mg four times per day until the bleeding subsides or is minimal. After oral estrogen has been discontinued, oral progestin (medroxyprogesterone acetate) 10 mg per day for 10 days should be initiated.6 Other options include high-dose oral monophasic contraceptives (containing 35 mcg ethinyl estradiol) three times a day for 7 days or medroxyprogesterone acetate 20 mg orally three times a day for 7 days.6 Tranexamic acid, an antifibrinolytic drug, dosed at 1.3 g three times a day for 5 days is another option that may be used for women with contraindications to hormonal therapy.7 For all patients, the contraindications to these therapies need to be considered before administration. In patients that are experiencing mild to moderate uterine bleeding, first-line therapy is usually oral estrogen–progestin contraceptives. Oral estrogen–progestin should contain 30 to 35 mcg ethinyl estradiol to reduce bleeding.6 For women with contraindications to estrogen therapy, levonorgestrel-releasing IUD is a reasonable choice.

Once the acute episode of bleeding has been controlled, multiple treatment options are available for long-term treatment of chronic AUB. These included OCs, progestin therapy (oral or intramuscular), levonorgestrel intrauterine system, tranexamic acid, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Duration of treatment depends on circumstances of bleeding, fertility or contraceptive needs, and the age of the patient. Anemic patients should receive iron supplementation.

Patients with known or suspected bleeding disorders may respond to hormonal and nonhormonal management. Consultation with hematologist is recommended. Patients with von Willebrand disease may respond to desmopressin. For severe bleeding, recombinant factor VIII and von Willebrand factor may be required to control bleeding. Avoid nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for patient with bleeding or platelet dysfunction.8

Surgical Management

The need for surgical treatment is based on the clinical stability of the patient, the severity of bleeding, contraindications to medical management, the patient’s lack of response to medical management, and the underlying medical condition of the patient. Surgical options include dilation and curettage (D&C), endometrial ablation, uterine artery embolization, and hysterectomy. The choice of surgical modality is based on medical factors plus the patient’s desire for future fertility.

Special Considerations

• Structural or anatomical causes concurrent with DUB. Fibroids, especially when large, can degenerate and be the primary source of bleeding. However, fibroids are common and their presence, especially if small, does not mean that they are the source of the bleeding. DUB may still be the primary diagnosis, as may cancer. DUB or infection can occur with an IUD in place, which may be retained if treatment of the underlying cause is successful.

• Postmenopausal bleeding

• For the woman not on hormones, the decision is clear. She needs a thorough investigation of the cause of the bleeding, including endometrial sampling, to rule out endometrial cancer. Hysteroscopy, TVS, or SIS may be needed.

• For the woman on hormones, an individual decision must be made based on her prior problems and her hormone regimen.

![]() Unopposed estrogen should not be used for long-term chronic AUB. If patients are identified as taking unopposed estrogen, they must have endometrial biopsy.

Unopposed estrogen should not be used for long-term chronic AUB. If patients are identified as taking unopposed estrogen, they must have endometrial biopsy.

![]() Although continuous or monthly progesterone is protective, endometrial cancer risk is not entirely removed by its addition to the estrogen regimen. Cancer must be ruled out by endometrial biopsy in the face of persistent bleeding.

Although continuous or monthly progesterone is protective, endometrial cancer risk is not entirely removed by its addition to the estrogen regimen. Cancer must be ruled out by endometrial biopsy in the face of persistent bleeding.

![]() Patients taking progesterone less than monthly should have endometrial sampling if bleeding is off schedule. It is reasonable to obtain an endometrial sample without prior ultrasonographic examination; the procedure is simple and yields definitive tissue, although it can also miss areas.

Patients taking progesterone less than monthly should have endometrial sampling if bleeding is off schedule. It is reasonable to obtain an endometrial sample without prior ultrasonographic examination; the procedure is simple and yields definitive tissue, although it can also miss areas.

![]() Patients taking tamoxifen are at higher risk for endometrial cancer; those taking raloxifene are at lower risk.9

Patients taking tamoxifen are at higher risk for endometrial cancer; those taking raloxifene are at lower risk.9

• Perimenopause. Although hormonal therapy remains controversial, it is now common in perimenopause. Decision-making must take into account the special circumstances of the bleeding. In some cases, one can treat the hormonal transition as DUB or hormonal bleeding, before doing more testing. In others, endometrial sampling and/or imaging is advised. It is better to err on the side of sampling/imaging.

• Cervical stenosis. If endometrial biopsy is impossible, an ultrasound scan with an acceptable endometrial stripe (less than 4 to 5 mm) may suggest that therapy for DUB is reasonable. If the endometrial stripe is greater than 8 mm, referral to a gynecologist (with probability of D&C) is indicated.

REFERENCES

1. Munro MG, Critchley HO, Broder MS, et al. FIGO classification system (PALM-COEIN) for causes of abnormal uterine bleeding in nongravida women of reproductive age. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2011;113:3–13.

2. Sweet MG, Schmidt-Dalton TA, Weiss PM. Evaluation and management of abnormal uterine bleeding in premenopausal women. Am Fam Physician 2012;85(1):35–43.

3. Committee on Practice Bulletins—Gynecology. Practice bulletin no. 128: diagnosis of abnormal uterine bleeding in reproductive-aged women. Obstet Gynecol 2012;120:197–206.

4. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG committee opinion no. 440. The role of transvaginal ultrasonography in the evaluation of postmenopausal bleeding. Obstet Gynecol 2009;114:409–411.

5. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG committee opinion no. 557: management of acute abnormal uterine bleeding in nonpregnant reproductive-aged women. Obstet Gynecol 2013;121:891–896.

6. Munro MG, Mainor N, Basu R, et al. Oral medroxyprogesterone acetate and combination oral contraceptives for acute uterine bleeding: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol 2006;108:924–929.

7. James AH, Kouides PA, Abdul-Kadir R, et al. Evaluation and management of acute menorrhagia in women with and without underlying bleeding disorders: consensus from an international expert panel. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2011;158:124–34.

8. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Adolescent Health Care; American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee Gynecologic Practice. ACOG committee opinion no. 451. Von Willebrand disease in women. Obstet Gynecol 2009;114:1439–1443.

9. Speroff L, Fritz M. Postmenopausal hormone therapy. In: Fritz MD, Speroff L, eds. Clinical gynecologic endocrinology and infertility. 8th ed. Baltimore, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2011:749–854.

| Pap Smear Evaluation for Cervical Cancer |

GENERAL PRINCIPLES

Definition

The Pap smear is the primary detection tool for cervical cancer. Since its widespread acceptance following publication of Papanicolaou and Traut’s paper in 1943,1 developed countries using the Pap smear as screening have had dramatic drops in rates of cervical cancer. Cervical cancer resulted in 3,939 deaths in the United States in 2010.2

Pathophysiology

The cervix is the inferior extension of the uterus. The vaginal portion is covered by squamous epithelium peripherally and centrally to a point referred to as the squamocolumnar junction (SCJ), where columnar (glandular) epithelium progresses from that point inward through the cervical os and into the body of the uterus. At birth, the SCJ is effaced more laterally on the vaginal portion of the cervix compared to the finding in a nonpregnant adult. A process known as squamous metaplasia results in the change from columnar to squamous epithelium between the original SCJ and the “new” SCJ. This area is referred to as the transformation zone (TZ). Virtually all cervical dysplasia and cancer occurs within the limits of the TZ, as it is the most “mitotically active” region of the cervix.

Risk factors for development of cervical cancer include human papillomavirus (HPV) exposure, early age of initiation of sexual activity, multiple sexual partners, cigarette smoking, and in utero diethylstilbestrol (DES) exposure. There is a dramatic difference (approximately threefold) between more and less developed countries in the incidence of cancer, primarily due to the availability of screening via the Pap smear.3

It is now well established that HPV is the causative agent of cervical cancer. This sexually transmitted virus exists in over 100 “strains,” most of which are not felt to be oncogenic. The known “high-risk” HPV subtypes are strains 16, 18, and approximately 10 others. Types 16 and 18 are responsible for approximately 70% of cervical cancers. Types 6, 11, and others are implicated as causes of condyloma. The other known risk factors for cervical cancer accelerate the oncogenicity of the high-risk subtypes; in addition, acquiring a new partner who exposes the patient to new low-risk strains accelerates the risk of cancer in a patient who already has high-risk strains of HPV.3

HPV is transmitted when infected genital epithelial cells desquamate during intercourse and bind to basal keratinocytes in areas of microtrauma on the sexual partner. The immune response of the host is usually inadequate to kill the virus because the virus does not kill the infected cells. It is believed that 20% of infections are handled through humoral immunity, and approximately 20% of infected patients have persistent infection despite therapy. The majority of patients, therefore, respond to therapy for warts or dysplasia with a lasting clinical remission. Patients with persistent infection may progress to low-grade disease, high-grade (cervical intraepithelial neoplasia, or CIN) disease, or invasive cancer. Severe dysplasia may still take up to 7 years to progress to invasive cervical cancer.3

DIAGNOSIS

Clinical Presentation

The great majority of patients who present with cervical cancer have had no screening for several years. The precursor conditions are imminently treatable when caught in any stage prior to invasive disease. Other than presenting for routine annual screening, patients may present with intermenstrual or postcoital bleeding, or have been referred for colposcopy because of a gross lesion.

History

Important aspects of the history, in addition to elucidation of risk factors mentioned above, include documentation of last menstrual period (LMP), any history of prior abnormal Pap or HPV testing, and history of prior treatment(s) for cervical disease. In older patients who may be menopausal, current or former hormone replacement therapy should be documented.4

Physical Examination

Screening should begin at age 21 with cytology alone every 3 years. Women less than age 21 should not be screened regardless of the time of first sexual intercourse. Women age 30 to 65 should be screened with cytology and HPV contesting every 5 years or with cytology alone every 3 years. It is not necessary to screen women after age 65 with prior negative screening. Direct visualization of the cervix with a speculum examination is necessary for collection of a sample for Pap smear. Patients should avoid douching or intercourse for 24 hours prior to the procedure. Metal speculums should be warmed with water; the new thin-layer preps do not require avoidance of lubrication for insertion of the speculum, but most pathologists still feel it should be avoided when possible. Note should be taken of any bleeding that is spontaneous or induced by contact with the instruments used to collect the sample. Any lesions, such as leukoplakia and Nabothian cysts, should be documented. A thorough bimanual examination is a standard part of an annual evaluation, with attention to size and position of the uterus and any nodularity or masses noted in the parauterine and adnexal regions.4

Laboratory Studies

Thin-layer (“thin-prep”) cytology is now the standard collection technique for Pap smear. This specimen has the same sensitivity as older, conventional smears and also allows for detection of HPV in the same sample. The “broom” is centered over the cervical os and twirled with pressure against the cervix two full rotations, and then deposited into the collection medium. In patients whom have had hysterectomy for advanced cervical dysplasia/cancer, the vaginal cuff is sampled. It is standard care now to request reflex testing for high-risk HPV subtypes if “atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance” (ASCUS) is found in the sample (discussed further under Pathologic Findings).4

Pathologic Findings

Adequacy of the collection is noted on the pathologist’s report; if endocervical cells are not detected in a patient who has a cervix, whether or not it should be recollected depends on age and HPV status. If the specimen is reported as inadequate, it should be recollected in 2 to 4 months. The Bethesda system adopted in 2001 includes the following:

• Statement of adequacy of the sample

• A general categorization of the findings, benign or malignant

• Descriptive diagnoses that may include benign changes (reactive, or secondary to infection). Epithelial changes may be squamous or glandular. The squamous components include ASCUS; HPV changes including “koilocytotic atypia,” low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (LSIL), high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HSIL), and squamous cell cancer (SCC). The glandular components include atypical glandular cells of undetermined significance (AGUS), adenocarcinoma in situ (AIS), and adenocarcinoma.5

TREATMENT

Nonoperative

Patients with Pap smears showing ASCUS with high-risk HPV subtypes present, and with LSIL, HSIL, or SCC need colposcopic evaluation. ASCUS without high-risk HPV present may repeat co-testing in 3 years. Those with cytology negative but HPV-positive test results can be followed with repeat co-testing in 12 months or HPV DNA typing may be done and those with HPV 16 or 18 should undergo colposcopy. Any other subtypes may repeat co-testing in 1 year. Patients with AGUS should undergo colposcopy, and endometrial biopsy if appropriate. Adenocarcinoma, in situ or otherwise should be referred to a gynecologic oncologist, as the source of the abnormal cells could be endometrial, tubal, ovarian, or even from non-gynecological abdominal metastasis.4

Operative

After colposcopy with appropriate biopsies and endocervical curettage, patients are managed on the basis of American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology (ASCCP) guidelines. Recommendations may include a diagnostic excisional procedure.4

Counseling

With the ease and efficacy of modern techniques for the management of Pap smear abnormalities, virtually all patients can be assured that they will never develop cervical cancer if they maintain appropriate follow-up visits for any abnormalities. Counseling about the risk factors for accelerating their risk of cancer (new contacts, smoking) is appropriate.4

Follow-Up

Telephone follow-up with abnormal Pap smear results is usually appropriate. Normal results are often notified by mail. Patients should be specifically told when their next screening is due. Guidelines for follow-up Pap, HPV testing, and/or colposcopy are well established by the ASCCP.4

Complications

Other than transient discomfort and occasional mild spotting, collection of Pap smears is not associated with any complications.

REFERENCES

1. Papanicolaou GN, Traut HF. Diagnosis of uterine cancer by the vaginal smear. Yale J Biol Med 1943;15:924.

2. U.S. Cancer statistics Working Group. United States cancer statistics: 1999–2010 incidence and mortality web-based report. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Center for Disease Control and Prevention and National Cancer Institute; 2013. www.cdc.gov/uscs. Accessed July 19, 2014.

3. Feldman S, Sirovich BE, Goodman A. Screening for cervical cancer: Rationale and recommendations. Uptodate. uptodate.com. Accessed July 19, 2014.

4. Saslow DS, Solomon D, Lawson HW, et al. American Cancer Society, American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology, and American Society for Clinical Pathology screening guidelines for the prevention and early detection of cervical cancer. CA Cancer J Clin 2012;62(3):147–172.

5. Solomon D, Davey D, Kurman R, et al. The 2001 Bethesda System terminology for reporting results of cervical cytology. JAMA 2002;287:2114–2119.

|

GENERAL PRINCIPLES

Definition

Acute pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) is an ascending infection of the female genital tract involving the uterus, fallopian tubes, ovaries, and adjacent pelvic structures.

Epidemiology

• More than 750,000 American women are diagnosed and treated for acute PID each year.1

• Direct medical costs of PID are estimated at $1.5 billion per year.2

Pathophysiology

• PID arises from the ascent of microorganisms from the vagina and cervix into the upper female genital tract.

• Although PID commonly stems from a cervicitis caused by Neisseria gonorrhoeae or Chlamydia trachomatis, there is evidence that an imbalance in the vaginal ecosystem, such as that seen in bacterial vaginosis, may also play a role in initiating the ascending infection.3

Etiology

• Microorganisms recovered from the upper genital tract of women with PID include C. trachomatis, N. gonorrhoeae, and anaerobic and aerobic bacteria of the endogenous vaginal flora, including Prevotella species, Peptostreptococcus, aerobic Streptococcus, Gardnerella vaginalis, Haemophilus influenzae, and enteric Gram-negative rods.4

• Epidemiologic risk factors that identify a patient at increased risk for acute PID include age less than 25 years, sexarche prior to age 16 years, multiple sexual partners, history of a sexually transmitted disease (including PID), the postinsertion period in intrauterine device (IUD) users, vaginal douching, and the presence of bacterial vaginosis.2,5,6

DIAGNOSIS

• As a result of the difficulty of diagnosis and its serious consequences if left untreated, guidelines for its diagnosis developed by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reflect a lowering of the diagnostic threshold.7

• Once competing diagnoses are adequately excluded in a woman at risk for sexually transmitted diseases (STDs), the CDC recommends that a provisional diagnosis of PID be made and a therapeutic trial of antibiotics be initiated in patients who meet one or more of the following criteria on pelvic examination:

• Cervical motion tenderness

• Uterine tenderness

• Adnexal tenderness

• Although not required, corroborating diagnostic laboratory, imaging, and surgical procedures should be sought in patients with an unclear diagnosis, no evidence of lower-genital-tract inflammation, and severe symptoms, or who fail to respond to therapy.3,7

Clinical Presentation

PID can present with a wide spectrum of nonspecific clinical symptoms and signs, ranging in degree from mild to severe.

History

• Lower abdominal pain, usually described as constant and dull, of less than 14-days duration is the most common complaint reported by patients with acute PID.

• Other manifestations include abnormal vaginal discharge, abnormal vaginal bleeding, gastrointestinal upset, and dysuria.

• Right upper quadrant pain secondary to perihepatitis (Fitz–Hugh–Curtis syndrome) is seen in up to 10% to 15% of patients.8

Physical Examination

• Cervical motion tenderness and adnexal tenderness (unilateral in up to 20% of cases) are the physical findings most frequently elicited in patients with PID.

• Rebound tenderness is present in two thirds of patients, and an adnexal mass or fullness in 16% to 49% of patients.

• Although a temperature of 38.3°C or higher supports the diagnosis, it is important to be aware that fever is a variable finding present in 24% to 60% of patients.9

Laboratory Studies

• White blood count. A leukocytosis is present only 60% of the time.

• Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR). Although classically elevated in PID, the ESR is normal (less than 15 mm per hour) in 25% of patients.

• C-reactive protein. An elevated C-reactive protein (CRP) >10 mg per dL has been found in up to 93% of patients with PID.10

• Examination of the male partner for the presence of urethritis can be a source of confirmatory evidence for the diagnosis of PID.

• A sensitive pregnancy test should be routinely obtained in all patients with suspected PID because of the great difficulty encountered in clinically differentiating patients with PID from those with ectopic pregnancy.11

• The finding of mucopurulent cervicitis or evidence of white cells on microscopic examination of a saline preparation of vaginal fluid is seen in the great majority of patients with PID. If both are absent, the diagnosis of PID is unlikely and alternative causes of pain should be considered.7,10,12

• Laboratory documentation of a cervical infection with N. gonorrhoeae or C. trachomatis corroborates the diagnosis of PID.7

• Cultures have traditionally been regarded as the gold standard.

• Nucleic acid amplification tests for the detection of C. trachomatis and N. gonorrhoeae are preferred.

Imaging

• Transvaginal pelvic ultrasonography. Sonographic findings supportive of the diagnosis include:

• Thickened, fluid-filled fallopian tubes

• Fluid in the cul-de-sac

• A complex, multiloculated adnexal mass

• Hyperemia on power Doppler transvaginal sonography3,13

• Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). MRI findings that support the diagnosis of PID include:

• Fluid-filled tubes

• Thickened tube walls with a dilated lumen

• An ill-defined adnexal mass with thickened walls containing fluid14,15

Surgical Diagnostic Procedures

• Endometrial biopsy. The histopathologic finding of neutrophil and plasma cell infiltration in the endometrial stroma obtained on biopsy confirms the diagnosis of PID.10

• Diagnostic laparoscopy

• Diagnostic laparoscopy is regarded by many authorities as the standard for the diagnosis of acute PID.

• Criteria required for the diagnosis include abnormal erythema and edema of the fallopian tubes and sticky exudate on tubal surfaces and from fimbriated ends.10

TREATMENT

• Once the diagnosis of PID is made, 2010 CDC guidelines favor hospitalization under the following circumstances:

• A surgical emergency, such as ectopic pregnancy or acute appendicitis, cannot be adequately excluded

• A tubo-ovarian abscess is present

• Pregnancy

• Failure to respond clinically to oral antimicrobial therapy

• Severe illness, nausea and vomiting, or high fever

• Inability to follow or tolerate an outpatient oral regimen7

Medications

Antibiotic therapy is the cornerstone of treatment for acute PID. Empirical, broad-spectrum antimicrobial therapy targeting N. gonorrhoeae, C. trachomatis, enteric Gram-negative facultative bacteria (including Escherichia coli), and certain anaerobic bacteria is recommended.

• Inpatient regimens. Parenteral therapy can be discontinued as soon as 24 hours after the patient has improved clinically. Regimens recommended by the 2010 CDC guidelines are as follows:

• Doxycycline 100 mg IV (or PO) q12h, plus cefoxitin 2 g IV q6h (or cefotetan 2 g IV q12h), followed by doxycycline 100 mg PO bid for a total of 14 days.

• Clindamycin 900 mg IV q8h, plus gentamicin 2.0 mg per kg IV, followed by 1.5 mg per kg IV q8h, followed by either doxycycline 100 mg PO bid, or clindamycin 450 mg PO four times daily to complete 14 days of total therapy.7

• Outpatient regimens. Suggested regimens are as follows:

• Cefoxitin 2 g IM plus probenecid 1 g PO concurrently, or ceftriaxone 250 mg IM, plus doxycycline 100 mg PO bid for 14 days with or without metronidazole 500 mg PO bid for 14 days.

• Other parenteral third-generation cephalosporin (e.g., ceftizoxime or cefotaxime), plus doxycycline 100 mg PO bid for 14 days with or without metronidazole 500 mg PO bid for 14 days.7

Surgery

• Surgical treatment has a limited role in the management of PID.

• Possible indications include the confirmation of the diagnosis in a patient failing to respond to therapy, excision of chronically infected pelvic organs, and draining of pelvic abscesses.

Nonoperative

• General supportive measures, such as bed rest, sexual abstinence until cure is achieved, hydration, and provision of antipyretics and appropriate analgesia, are recommended in the management of PID.

• Although there is no evidence that IUDs have to be removed in women diagnosed with acute PID, if the IUD is not removed CDC guidelines mandate that close clinical follow-up be provided.

Follow-Up

• Patients should be seen within 3 days after initiation of therapy.

• Patients who fail to respond require careful reevaluation of both the diagnosis and therapy.

• Male sex partners who have had contact with the patient during the preceding 60 days should be evaluated and provided empiric treatment for Chlamydia and gonorrhea. If more than 60 days have elapsed since the patient’s last sexual intercourse, the patient’s most recent sexual partner should be treated.

• Patients should be provided counseling regarding safe sexual behavior, the use of condoms as a means for preventing the transmission of STDs, and the advisability of HIV testing.

• Periodic screening for Chlamydia is recommended in sexually active women at risk for this infection, such as unmarried women 25 years of age or younger.16

Complications

• Tubal factor infertility is seen in 8% to 12% of patients after one episode of PID, 20% to 25% after two episodes, and 40% to 50% after three episodes or more.

• Chronic pelvic pain has been reported in 15% to 20% of patients after PID.

• The risk of ectopic pregnancy is increased 3- to 10-fold in a patient with a history of PID.6,8

REFERENCES

1. Sutton MY, Sternberg M, Zaidi A, et al. Trends in pelvic inflammatory disease hospital discharges and ambulatory visits, United States, 1985–2001. Sex Transm Dis 2005;32:778–84.

2. Gradison M. Pelvic inflammatory disease. Am Fam Physician 2012;85:791–796.

3. Soper DE. Pelvic inflammatory disease. Obstet Gynecol 2010;116:419–428.

4. Sweet RL. Treatment of acute pelvic inflammatory disease. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol 2011;2011:561909. doi: 10.1155/2011/561909.

5. Simms I, Stephenson JM, Mallinson H, et al. Risk factors associated with pelvic inflammatory disease. Sex Transm Infect 2006;82:452–457.

6. Taylor BD, Darville T, Haggerty CL. Does bacterial vaginosis cause pelvic inflammatory disease? Sex Transm Dis 2013;40:117–122.

7. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2010. MMWR 2010;59(No. RR-12):63–69.

8. Banikarim C, Chacko MR. Pelvic inflammatory disease in adolescents. Semin Pediatr Infect Dis 2005;16:175–180.

9. Quan M. Pelvic inflammatory disease: diagnosis and management. J Am Board Fam Pract 1994;7:110.

10. Jaiyeoba O, Soper DE. A practical approach to the diagnosis of pelvic inflammatory disease. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol 2011;2010:753037. doi: 10.1155/2011/753037.

11. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG practice bulletin no. 94. Medical management of ectopic pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 2008;111:1479–1485.

12. Mitchell C, Prabhu M. Pelvic inflammatory disease: current concepts in pathogenesis, diagnosis and treatment. Infect Dis Clin N Am 2013;27:793–809.

13. Cicchiello LA, Hampe UM, Scoutt LM. Ultrasound evaluation of gynecologic causes of pelvic pain. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am 2011;38:85–114.

14. Li W, Zhang Y, Cui Y, et al. Pelvic inflammatory disease: evaluation of diagnostic accuracy with conventional MR with added diffusion-weighted imaging. Abdom Imaging 2013;38:193–200.

15. Vandermeer FQ, Wong-You-Cheong JJ. Imaging of acute pelvic pain. Clin Obstet Gynecol 2009;52:2–20.

16. Gottlieb SL, Xu F, Brunham RC. Screening and treating chlamydia trachomatis genital infection to prevent pelvic inflammatory disease: interpretation of findings from randomized controlled trials. Sex Trans Dis 2011;40:97–102.

|

GENERAL PRINCIPLES

Definition

Menopause is defined as the failure of ovarian follicle development in the presence of adequate gonadotropin stimulation, resulting in the cessation of spontaneous menstrual periods. A woman is considered to be postmenopausal after 12 months of amenorrhea without another physiologic or pathological cause.

Epidemiology

The average age for menopause is 51 years.1 Factors that can lower the age of menopause include smoking, hysterectomy, oophorectomy, genetic disorders, autoimmune disorders, high altitude, and a history of chemotherapy or radiation.

Classification

Menopause may be secondary to surgical intervention or drug effect, particularly chemotherapeutic agents. Evidence of menopause before 40 years of age is considered premature ovarian failure and usually necessitates a workup.

Pathophysiology

Vasomotor symptoms are not fully understood but may relate to estrogen withdrawal and a narrowed thermoregulatory zone, resulting in increased sensitivity to temperature change. Symptoms are often worse in obese women, possibly due to the insulating effects or endocrine effects of adipose tissue. Vasomotor symptoms are also associated with depression, anxiety, smoking, and low socioeconomic status.1 The vaginal epithelium is estrogen-dependent, and declining estrogen levels lead to thinning of the vaginal mucosa, loss of rugae, and narrowing and shortening of the vagina. There is also a loss of subcutaneous fat in the labia majora. Vaginal pH increases, altering vaginal flora, and vaginal secretions decrease. These changes may result in infection, fissures or tears, fusion of labia minora, and shrinking of the clitoris and urethra. Decreased libido may be secondary to dyspareunia, stress, depression, or hormonal changes. Estrogen deficiency leads to decreased osteoblastic activity with increased osteoclastic activity, resulting in osteoporosis and risk for fractures.

DIAGNOSIS

Clinical Presentation

Perimenopause, or the menopausal transition, often begins as early as 6 years before the last period.1 During this time, women may experience signs or symptoms such as irregular periods, mood changes, insomnia, weight gain, bloating, vaginal dryness, decreased libido, headaches, or vasomotor instability (hot flashes). Hot flashes, which affect 80% of perimenopausal women, are described as intense warmth and profuse sweating, which may be accompanied by palpitations and redness of the skin. They last from seconds to minutes, rarely up to 1 hour, and may occur as often as 20 times per day. As ovarian response to gonadotropins declines in the postmenopausal years, associated symptoms decrease, also. After menopause, fibroids, endometriosis, and adenomyosis become less symptomatic. Prolapse of genitourinary organs may occur as loss of pelvic muscle tone occurs. Atrophic vaginitis may lead to insertional dyspareunia. Atrophic cystitis may mimic a urinary tract infection (UTI), and is also a risk factor for UTIs.

History

The history should focus on gynecologic and cardiovascular history, family history of breast or uterine cancer, and risk factors for osteoporosis and coronary artery disease. Note the frequency and severity of menopausal symptoms and their effect on the patient’s overall function.

Physical Examination

The physical examination should be complete, including vital signs, thyroid, cardiovascular, breast, and pelvic examination. Pelvic examination at first reveals reddened vaginal epithelium as the skin thins and capillaries are more visible. After time, the number of capillaries decreases and the vaginal epithelium becomes pale. Rugation of the vaginal mucosa decreases, the uterus and ovaries diminish in size, and loss of pelvic tone may lead to prolapse. A palpable ovary on bimanual examination in a postmenopausal woman is abnormal and warrants a full evaluation. Pap smear should be completed if not up-to-date.

Laboratory Studies

A persistently elevated follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) level confirms the diagnosis of menopause. Eventually FSH will increase 10- to 20-fold, while luteinizing hormone (LH) will increase to three times that of premenopausal levels. Conversely, estradiol and inhibin levels decline. Estradiol, inhibin, and LH values are not necessary to diagnose menopause. If the diagnosis is uncertain, repeat measurement of FSH and LH every 2 to 3 months may be helpful. Laboratory testing may include thyroid function tests or other tests as indicated by history and physical examination. Urine culture should be done for women complaining of UTI symptoms, even if they may be related to atrophic cystitis.

Imaging

Imaging is not necessary to diagnose menopause. Pelvic ultrasound to assess for endometrial hyperplasia is recommended in postmenopausal uterine bleeding. Bone densitometry testing should be done starting at 65 years of age or earlier for those with risk factors. Bone loss accelerates in the late perimenopausal years and continues after menopause. Mammograms are currently recommended for all women ages 50 to 74 and may be indicated for certain women at younger ages.

Surgical Diagnostic Procedures

Endometrial biopsy to rule out endometrial cancer should be performed on women with abnormal uterine bleeding and an endometrial stripe measuring more than 5 mm by ultrasound.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of vasomotor instability includes alcohol withdrawal, anxiety disorders, carcinoid tumor, epilepsy, insulin reaction, pheochromocytoma, thyrotoxicosis, and drug effects.

TREATMENT

Treatment of menopausal symptoms should be tailored to the severity of symptoms. Mild symptoms may be treated with behavioral modification, whereas more severe symptoms may require pharmacologic therapy. There is a significant placebo effect in the treatment of hot flashes, with up to 25% reduction in the number of hot flashes with placebo in controlled trials.1

Behavioral

Nonpharmacologic treatments for hot flashes include fans; cool drinks; lower ambient temperature; loose or layered clothing; and avoidance of alcohol, caffeine, and spicy foods. Risk of osteoporosis may be reduced by weight-bearing exercise and smoking cessation.

Medications

Estrogen has been used in the treatment of perimenopausal symptoms for more than 50 years. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), gabapentin, and clonidine can be useful alternatives to hormonal therapies for treatment of vasomotor symptoms. Paroxetine is the only nonhormonal treatment approved by the FDA for treatment of vasomotor symptoms. The FDA has approved ospemifene for treating moderate-to-severe dyspareunia in postmenopausal women. Estrogens, selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs), and bisphosphonates are approved for the prevention and treatment of osteoporosis.

• Hormone replacement therapy (HRT) is the most effective therapy for vasomotor symptoms of menopause. HRT may also improve mood symptoms, fatigue, incontinence, and vaginal dryness. Low-dose estrogen (0.3 to 0.45 mg per day conjugated estrogen, 0.5 mg per day micronized estradiol, 5 mcg per day ethinyl estradiol, or 0.025 to 0.0375 mg per week transdermal estradiol) or ultra-low-dose estrogen (0.25 mg per day micronized estradiol or 0.014 mg per week transdermal estradiol) regimens have a better side effect profile and may be effective. HRT may be administered orally or transdermally in the forms of patches, gels, or sprays. Contraindications to estrogen therapy include undiagnosed vaginal bleeding, liver disease, pregnancy, venous thromboembolism (VTE), and personal history of breast cancer. Well-differentiated early endometrial cancer after complete treatment is no longer an absolute contraindication.

• Risks of HRT: The Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) study, a large randomized controlled trial (RCT) of healthy women 50 to 77 years old, demonstrated that after an average of 5 years of combined HRT, women had slightly increased risk of coronary artery disease, stroke, VTE, and breast cancer and a decreased risk of colon cancer and fractures.2 For women receiving estrogen without progestin, there was an increased risk of VTE but not of cardiovascular disease or breast cancer.3 It should be noted that these women were already past the menopausal transition, so it is difficult to extrapolate these data to general populations. Later analysis of the WHI data in women 55 to 60 years of age and within 10 years of menopause suggests a possible cardioprotective effect of HRT for these younger women. However, follow-up of these women at 13 years confirmed that the risks of combined HRT for primary prevention outweigh the benefits.4 A Cochrane review of HRT completed in 2012 similarly showed that HRT should not be used for primary prevention because the risks outweigh the benefits. Different forms of HRT may have different risk profiles based on observational studies, and additional randomized trials are needed to further investigate this. Yearly mammograms are necessary for all women on HRT. An on-going discussion should be held at each healthcare maintenance visit regarding symptoms and treatment, with the goal of using the lowest possible dose of HRT for the shortest amount of time possible for each individual patient. Discontinuation may lead to return of vasomotor symptoms in up to half of women, regardless of age and duration of use. There are insufficient data to recommend tapering the dose versus abrupt cessation.

• Estrogen/progestin combination therapy is necessary in patients with an intact uterus or with endometriosis remaining after hysterectomy to avoid endometrial hyperplasia and development of endometrial cancer. Some studies suggest that addition of progestin to estrogen replacement leads to greater improvement of vasomotor symptoms. The progestin in combination therapy may be dosed in either a continuous or a cyclic manner.

• Continuous progestin dosing causes breakthrough bleeding in half of women in the first 6 months of therapy. Endometrial biopsy is indicated for breakthrough bleeding beyond this time frame. The progestin dose may be doubled if no pathology is found on biopsy.

• Cyclic progestin dosing causes less breakthrough bleeding but may worsen migraine headaches. Nonsmoking perimenopausal women may use low-dose oral contraceptive pills for regulation of menses, relief of vasomotor symptoms, and contraception.

• Progestin-only therapy has some evidence of relieving vasomotor symptoms. However, there are limited data on the safety of progestin alone. Furthermore, the rate of breast cancer was higher in the combined arm than in the estrogen-only arm of the WHI, indicating a possible correlation between progestin therapy and breast cancer risk.

• Vaginal estrogen in the form of cream, ring, or tablet may reverse vaginal atrophy if dosed daily for 1 to 2 weeks. This benefit is maintained with two to three treatments per week or a decreased daily dose. There is theoretical concern for endometrial hyperplasia or cancer in long-term vaginal estrogen therapy. However, a Cochrane meta-analysis showed no increase in either of these outcomes, so addition of progestin is not necessary for patients using vaginal estrogen.1 Vaginal estrogen at low doses may be used indefinitely. The 3-month estradiol-releasing vaginal ring is often easier to use than daily tablets or creams.