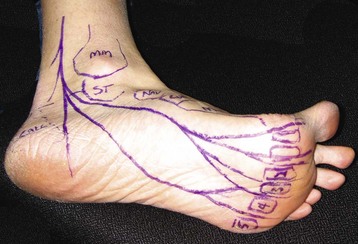

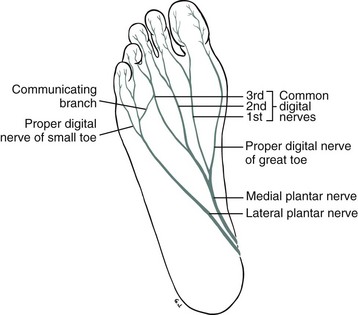

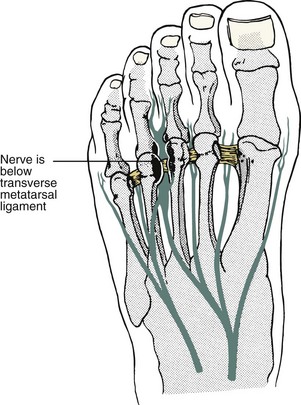

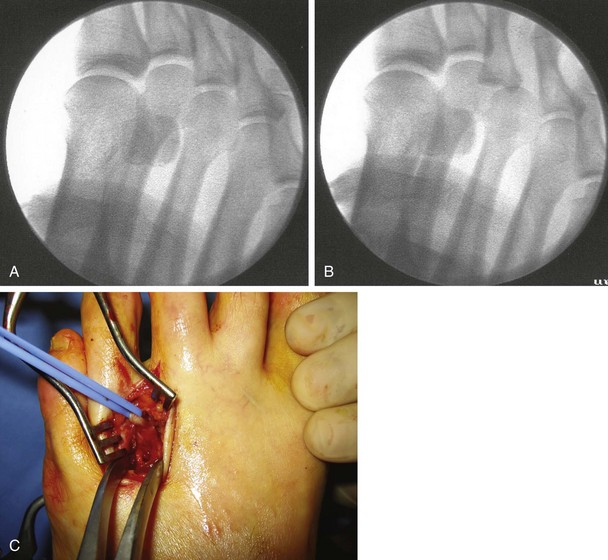

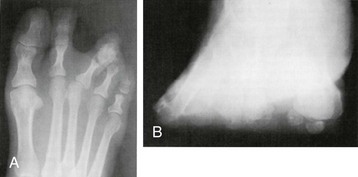

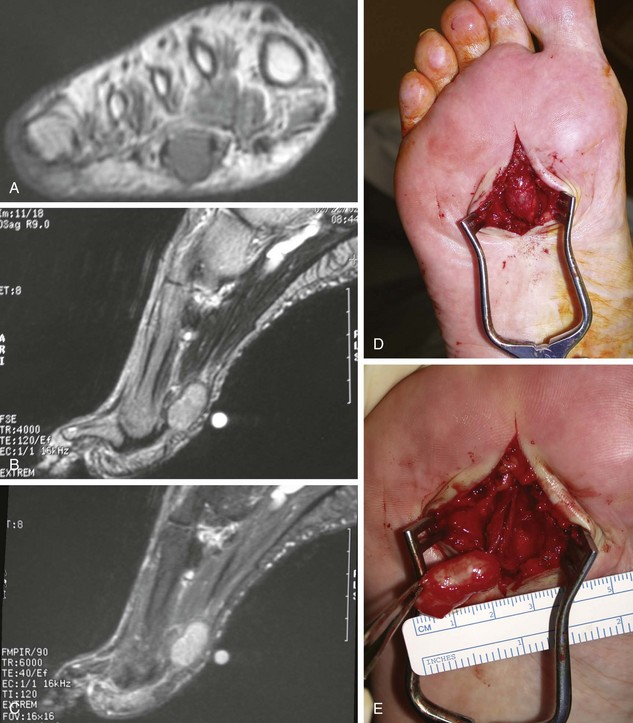

Chapter 12 The more challenging diagnostic cases are dynamic and occur only with mechanical stresses, such as walking, running, or wearing certain shoes. Some nerve disorders occur as a double-crush syndrome. In the double-crush syndrome, a more proximal nerve dysfunction (radiculopathy), which may be subclinical, causes impairment of axoplasmic flow and diminishes the threshold for distal nerve symptoms from focal disease.41,212 The role of metabolic, endocrinologic, chemical, pharmacologic, or rheumatologic conditions in nerve physiology and function must be recognized as creating or enhancing nerve dysfunction. Occasionally, the clinical problem has been aggravated by surgery, and the preoperative condition must be distinguished from the postoperative condition. The foot and ankle specialist is challenged to elucidate the differences between the symptoms from mechanical nonneurologic symptoms and those that arise from the nerves. Awareness of these features and manifestations of these conditions will help the specialist design an effective treatment plan and anticipate the outcome of the interventions. The history of the interdigital neuroma has been long and colorful. Kelikian’s detailed chronology of the history31 is briefly summarized here. The condition was first described in 1845 by the Queen’s Surgeon-Chiropodist Lewis Durlacher.16 He described a “form of neuralgic affection” involving “the plantar nerve between the third and fourth metatarsal bones.” In 1876 T.G. Morton39 related the problem to the fourth metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joint and suspected a neuroma or some type of hypertrophy of the digital branches of the lateral plantar nerve (LPN). In 1877 Mason37 reported a case of pain around the second MTP joint and suspected involvement of a digital branch of the medial plantar nerve. In 1893 Hoadley27 actually explored the digital nerves under the painful area, “found a small neuroma,” excised it, and claimed that he obtained a “prompt and perfect cure.” In 1912 Tubby55 reported observing on two occasions that the plantar digital nerves were congested and thickened. In 1940 Betts8 stated that “Morton’s metatarsalgia is a neuritis of the fourth digital nerve.” In 1943 McElvenny38 stated that it was caused by a tumor involving the most lateral branch of the medial plantar nerve. In 1979 Gauthier19 speculated that the condition was a nerve entrapment, an idea supported anatomically by others.22,32 Studies by Lassmann32 and Graham and Graham22 have demonstrated that most, if not all, of the histologic changes in the nerve occur beyond the transverse metatarsal ligament and that the nerve proximal to the ligament appears to be normal. These authors demonstrated quantitatively that there was a decrease in the number of thick myelinated fibers, decreased diameter in the individual nerve fibers as a result of attenuation of their myelin sheaths, and increased nerve and vesicular width. Alterations in the interdigital arteries could not be correlated with the alterations found in the nerves. Hyalinization of vessel walls has been observed in patients with interdigital neuroma, but it has also been observed in control material in patients without interdigital neuroma. In a study of 133 patients with a clinical diagnosis of Morton’s syndrome, light and electron microscopic investigations revealed that in the early stages of the disease the histologic findings are dominated by certain alterations of the nerves independent of alterations of the interdigital vessels. These alterations include sclerosis and edema of the endoneurium, thickening and hyalinization of the walls of the endoneurial vessels caused by multiple layers of basement membrane, thickening of the perineurium, deposition of an amorphous eosinophilic material built up by filaments of tubular structures, demyelinization and degeneration of the nerve fibers without signs of Wallerian degeneration, and local initial hyperplasia of unmyelinated nerves, followed by degeneration. These authors concluded that Morton’s syndrome is probably caused by an entrapment neuropathy predominantly characterized by the deposition of an amorphous eosinophilic material, followed by a slow degeneration of the nerve fibers. Giannini et al20 reported on the histopathology in 63 cases and found intraneural (epineurium and perineurium) fibrosis and sclerohyalinosis and an increase of the elastic fibers in the stroma. They also found hyperplasia of the muscle layer, very evident internal elastic lamina, and proliferation of small vessels in the muscle layer and adventitia in the vessels. From an anatomic standpoint, the medial plantar nerve (MPN) has four digital branches (Fig. 12-1). The most medial branch is the proper digital nerve to the medial aspect of the great toe. The next three branches are the first, second, and third common digital nerves and are distributed to both the medial and the lateral aspects of the first, second, and third interspaces, respectively. The lateral plantar nerve (LPN) divides into a superficial branch (which splits into a proper digital nerve to the lateral side of the small toe) and a common digital nerve to the fourth interspace. The common digital nerve often has a communicating branch that passes to the third digital branch of the MPN in the third interspace. Researchers have speculated that because the common digital nerve to the third interspace consists of branches from the medial and lateral plantar nerves, the common digital nerve has increased thickness and is therefore more subject to trauma and possible neuroma formation (Fig. 12-2).30 In an anatomic dissection of 71 feet, Levitsky et al34 observed that a communicating branch to the nerve to the third web space was present in only 27% of specimens and was absent in 73%. This anatomic finding seems to indicate that the communicating branch has little relation to the cause of interdigital neuroma. The authors did observe, however, that the second and third interspace was significantly narrower than the first and fourth and postulated that this further indicated the possibility of an entrapment. The frequency of the communicating branch was confirmed by Govsa et al.21 They studied the anatomy of the communicating branches of the common plantar digital nerves between the fourth and third nerves in 50 adult male cadavers and found it was present in 28% of the feet. The mobility that occurs between the medial three rays and the lateral two rays may be a reason for the increased incidence of neuromas in the third web space. The medial three rays are firmly fixed at the metatarsocuneiform joints, whereas the fourth and fifth metatarsals are fixed to the cuboid, which is more mobile. This anatomic fact results in increased mobility in the third web space, and the increased motion can result in trauma to the nerve or possibly the development of an enlarged bursa, which can secondarily place pressure on the nerve. The significant number of neuromas found in the second web space in part negates this as the main cause for the development of a neuroma.35 During normal gait, dorsiflexion of the metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joints along with the action of the plantar aponeurosis causes plantar flexion of the metatarsal heads and, in theory, exposes the nerve to increased trauma (Fig. 12-3). The incidence of interdigital neuromas is 8 to 10 times more common in women, whose toes are often hyperextended at the MTP joint by high-fashion footwear, and this is probably a significant factor. Rather than increased trauma to the nerve itself resulting from long-term hyperextension of the MTP joints, the nerve may be tethered beneath the transverse metatarsal ligament, which results in the entrapment neuropathy previously discussed (Fig. 12-4). Extrinsic pressure against the nerve can result from a mass above the transverse metatarsal ligament or below the ligament. Anatomically, a bursa is normally present between the metatarsal heads and is located above the transverse metatarsal ligament. Bossley and Cairney10 studied this bursa by injecting dye in cadaver feet and demonstrated extension of the bursa distal and proximal to the transverse metatarsal ligament in the third web space. They did not observe extension of the bursa in the fourth web space. They hypothesized that the bursa can cause inflammation resulting in secondary neurofibrosis of the nerve but did not believe that the bursa caused a compressive force against the nerve. Awerbuch and Shephard3 noted similar findings of an inflamed intermetatarsal bursa in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, which they believed resulted in an alteration in the interdigital nerve, as well as some direct compressive effect on the nerve by the enlarged bursa. Degeneration of the capsule of the MTP joint from unknown causes can result in a localized inflammatory response, but the nerve is not usually involved because the inflammation is above the transverse metatarsal ligament. Such deterioration of the capsule, however, can cause deviation of the proximal phalanx, usually of the third toe, in a medial direction. This in turn results in lateral deviation of the third metatarsal head against the fourth. The pressure can result in compression of bursal material present above the ligament and subsequently pressure against the underlying nerve. The deviation of the toe or instability of the MTP joint could also result in traction on the nerve, which could lead to disease (Fig. 12-5). Clinical symptoms of a neuroma are observed in approximately 10% to 15% of patients with deviation of the MTP joint, which may be accounted for by this anatomic malalignment (Fig. 12-6). Mann and Reynolds35 performed a critical analysis of 56 patients in whom 76 neuromas were excised. There were 53 women and 3 men. This represents a greater female-to-male ratio than that observed by Bradley et al,11 who reported a ratio of 4 : 1. The average age of the patient in the Mann and Reynolds35 series was 55 years (range, 29-81 years). An interdigital neuroma is usually unilateral, although bilateral neuromas were observed in 15% of the patients. The development of two neuromas simultaneously in the same foot rarely occurs; in a review of 89 neurectomies, Thompson and Deland54 concluded that the incidence was probably less than 3%. The majority of the literature reports that the neuroma usually involves the third interspace, but an equal number of neuromas in the second and third interspaces have been noted. This same distribution was subsequently noted by Hauser25 but was not supported by Graham et al,23 who noted that there were twice as many neuromas in the third web space as the second. An interdigital neuroma of the first or fourth interspace is rare and probably does not exist as a clinical entity. Table 12-1 lists the preoperative symptoms by percentage in patients with interdigital neuroma.35 Table 12-1 Preoperative Symptoms of Interdigital Neuroma The diagnosis of an interdigital neuroma is based on the patient’s history and the physical findings. No electrodiagnostic studies are useful unless a peripheral neuropathy or radiculopathy is suspected. Radiographs are helpful to assess the foot in general and to identify an underlying bone or joint disease. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be useful in some cases to rule out other pathologies but is not warranted for establishing the diagnosis (Fig. 12-7). Similarly, ultrasound may be helpful in some situations, but the rate of false positives and negatives is too high to depend on the test. In some cases, it may be necessary to reevaluate the patient several times before one makes the diagnosis of an interdigital neuroma if the patient’s symptoms are atypical. Next, the physician carefully palpates the interspaces, starting just proximal to the metatarsal heads and proceeding distally into the web space. This usually reproduces the patient’s pain, which often radiates out toward the tips of the toes. It is important when performing this test to ensure that there is no inadvertent compression of the dorsal tissues as a counterforce to the plantar pressures that are directed dorsally. The physician should press the web space with one finger plantarly, using the other hand to stabilize the foot over a broad area of the midfoot or forefoot or against the resistance of the patient’s foot alone (Fig. 12-8). Concomitant dorsal pressure can lead to discomfort from other etiologies that must be distinguished from interdigital neuralgia. The web spaces are reexamined, and pressure is applied in a mediolateral direction with one hand to increase pressure on the tissue between the metatarsal heads. This maneuver often results in a significant crunching or clicking feeling (the Mulder sign),40 most often in the third web space and occasionally in the second web space. The maneuver can reproduce the patient’s pain and, if so, is diagnostic of an interdigital neuroma. The presence of only a crunching or clicking feeling in the web space without reproduction of the patient’s pain does not indicate a neuroma. Examination of a normal foot can demonstrate a crunching or clicking feeling, particularly in the third web space and occasionally in the second. It is unusual to elicit this crunch or click in the first and fourth web spaces. This test is not as helpful after a prior neuroma resection. When the plantar aspect of the foot is palpated, occasionally a mass representing a small synovial cyst or ganglion is observed. Usually, this mass is less than 1 cm in diameter and can be rolled beneath the examiner’s fingers. When the mass is associated with a web space, pressure against the mass often reproduces the patient’s symptoms. A sensory examination rarely demonstrates any deficit in the patient with a neuroma. At times, the patient’s physical examination is not conclusive, and the patient needs to be reevaluated on several occasions to ensure that the symptom complex indeed indicates a neuroma. If there is pain around an MTP joint as well as in the web space, caution is advised in making the diagnosis of a neuroma because early degeneration of the plantar pad, early synovitis of the MTP joint, or some degeneration of the plantar fat may be present. It is useful to stress the MTP joint by checking for a dorsal drawer sign and instability of the MTP and induction of symptoms. When undertaking this maneuver, the physician must secure the base of the toe at the proximal phalanx without inadvertently pressing on the nerve. With the other hand securing the foot at the metatarsals, slight traction is applied to the toe, and an attempt is made to translate the base of the proximal phalanx dorsally. The adjacent and contralateral toes should be checked to determine the baseline joint laxity for the patient (Fig. 12-9). This test may be positive with instability or synovitis, which can coexist with neuralgia, but if the pain is not reproduced with the symptoms, then instability or synovitis is not triggering the neuralgia, or the patient’s forefoot pain may be coming from another condition. Schon’s (LCS’s) opinion is that MRI has not been demonstrated as effective in the diagnosis of an interdigital neuroma. This has been substantiated by a study by Bencardino,5 who found a lack of correlation of an MRI finding of a neuroma and symptoms in 33% of patients. If there is a question about the presence of other causes of the patient’s pain, an MRI may be performed in the prone position57 using a combination of contrast enhancement and fat suppression.53 One study by Biasca et al9 suggested that a more favorable result could be achieved after neuroma resection when the nerve has a transverse measurement larger than 5 mm on MRI scans. Ultrasound is operator-dependent,48 and although there are proponents of this imaging technique,33,43,44 the authors and others do not find it a useful modality.45,46 This impression has been substantiated in a report by Sharp et al.50 These authors looked at the accuracy of preoperative clinical assessment, ultrasound, and MRI and compared these findings to intraoperative histology and the clinical outcome. They found the accuracy of the ultrasound and MRI was similar and dependent on lesion size. Small lesions were not well visualized on ultrasound. There was no correlation among the size, the pain score, or the change in pain score after surgery. Reliance on either ultrasound or MRI would have led to an inaccurate diagnosis in 18 of 29 cases. The predictive values attained by clinical assessment surpass imaging with one or both modalities. Lidocaine can be injected into the suspected web space for diagnostic purposes. The recommended dose is 1 or 2 mL of anesthetic placed below the transverse metatarsal ligament. Although complete relief of symptoms can be obtained, caution is advised in interpreting this as confirming an interdigital neuroma because this injection may also relieve pain from local pathologic conditions, such as degeneration of the joint capsule or plantar plate. Younger and Claridge60 performed a study to determine the role of a diagnostic block in predicting the results of surgery. In 37 patients with 41 excisions (7 patients with revisions), 24% of the primary procedures were failures despite relief with a block, and 43% of the 7 revision procedures were failures. Schon performed a recent cadaveric study comparing injection of 1 mL of fluid versus 2 mL into the third web space and found increased extravasation of fluid with the 2-mL dose. Hembree et al26 found that injection of 1 mL of fluid was sufficient to effectively envelope the nerve but not selective enough to be used diagnostically because, even with a lower dose, there was still a high rate of extravasation into adjacent web spaces. Administration of cortisone can be useful in about one third of patients, but cortisone can cause deterioration of the joint capsule or possibly the plantar fat. Only infrequently should more than one hydrocortisone injection be made into the web space. In some patients, medial or lateral deviation of the adjacent MTP joint has developed after multiple steroid injections, presumably from damage to a collateral ligament (Fig. 12-10). Decreasing the volume effect of the injection can help diminish the risk of damage to the MTP joint capsule, ligament, or tendon. This can be accomplished by injecting proximal to the MTP joint below the intermetatarsal ligament as opposed to more distally. In addition, if during the injection the toes begin to spread apart, the injection should be stopped. If the deviation is noted after an injection, the toes should be supported by taping.

Disorders of the Nerves

Interdigital Neuroma

Etiology

Anatomic Factors

Extrinsic Factors

Symptom Complex

Symptom

Patients Affected (%)

Plantar pain increased by walking

91

Relief of pain by resting

89

Plantar pain

77

Relief of pain by removing shoes

70

Pain radiating into toes

62

Burning pain

54

Aching or sharp pain

40

Numbness in toes or foot

40

Pain radiating up foot or leg

34

Cramping sensation

34

Diagnosis

Physical Examination

Diagnostic Studies

Disorders of the Nerves