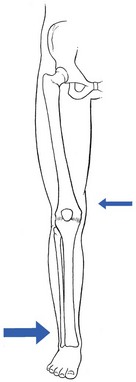

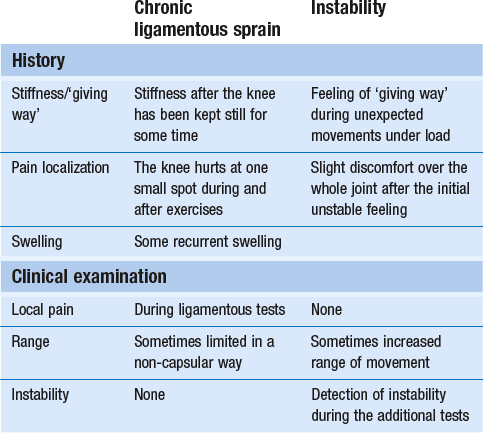

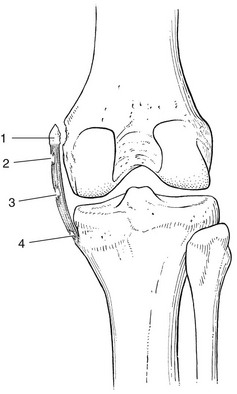

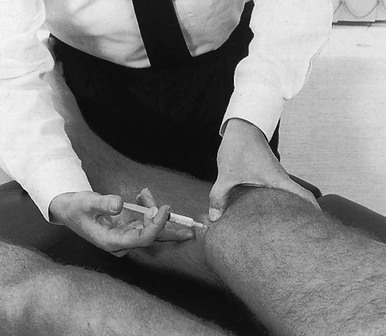

53 Ligamentous lesions at the knee are quite common. The joint is relatively uncovered by muscles, which makes it vulnerable to direct injury. Furthermore, the indirect forces acting on the knee have a large leverage, whereas the active and passive stabilizers of the joint have only a small leverage (Fig. 53.1) and thus give very inadequate protection. We firmly believe that immobilization is never a good method. If there is a serious grade III lesion (see below) in a young athlete and instability is feared, the patient should be sent for surgery. If, for one reason or another, the patient is not treated surgically, early mobilization, deep transverse friction and functional treatment should be used. This treatment regime gives the needed physiological stimulus for quick and proper healing of the lesion and prevents the formation of adhesions, so often the cause of persistent trouble.1 Ligamentous injuries can also be classified according to which structure has been damaged. The commonest injuries are at the medial collateral and the anterior cruciate ligaments. Sometimes these occur together and in combination with a torn medial meniscus – the ‘unhappy triad’, or the triad of O’Donoghue2,3 – or in combination with a tear of the lateral meniscus.4 Lesions at the lateral collateral ligament and the posterior cruciate ligament are rare. In our experience, tears at the medial coronary ligament are very common; however, these are often misdiagnosed as medial collateral tears or meniscus lesions. This temporal division is important in choice of treatment (Table 53.1). Table 53.1 Classification of ligamentous injuries according to severity, structure and time Even in the era of arthroscopy, a clinical approach to ligamentous lesions continues to be vital. In the acute stage, information obtained from the history and clinical examination enables the examiner to make the distinction between serious and mild lesions. If symptoms and signs warrant, the patient is then referred for further assessment by arthroscopy.5 It is vital to obtain a very detailed history of the mechanism that has led to the injury, as summarized in Box 53.1, especially in acute sprains of the knee. • The injury: at the moment of injury, what was the position of the knee, what forces acted where on the knee and in which directions were they applied? • The initial symptoms: what was the immediate result of the trauma? Where was the initial pain? Was there immediate swelling? Was there immediate functional incapacity caused by locking or instability or could the patient continue activities? Did pain, swelling and functional disability appear only after a certain lapse of time? • The evolution: what was the evolution of pain, swelling and disability after the first few days? • Treatment received: what sort of treatment did the patient receive and what was the result? In long-standing cases, the current symptoms should be ascertained: The functional examination described in Chapter 50 is carried out. In acute cases, the ligamentous tests will sometimes be overshadowed by the capsular pattern of the traumatic arthritis, which makes it very difficult to estimate the degree of damage. In subacute and chronic cases, the capsular signs have largely subsided and the tests of ligamentous integrity become more informative. Sometimes, laxity is found during the routine examination, in which case instability tests are then carried out (see online chapter Disorders of the inert structures: ligamentous instability). Sometimes, it is not so much instability but rather pain and limitation of a non-capsular type that are detected; these indicate the formation of adhesions around the healed tissue. In acute ligamentous lesions at the knee, the history will be what first indicates severity. A few hours after a serious sprain, the knee will start to hurt considerably and develop a distinct capsular pattern, protected by muscle spasm that makes it almost impossible to perform ligamentous tests. In order to distinguish between a serious injury and a less important lesion, a number of elements gained from the history may be of value (Table 53.2). Table 53.2 Acute ligamentous lesions: contrasting histories of serious and less serious lesions Because the treatment is quite different, it is vital to differentiate between instability as the result of a total ligamentous rupture and chronic ligamentous adhesions leading to a ‘self-perpetuating inflammation’. Once again, history and clinical examination are the first approach to differentiate between these conditions and, in instability, to estimate its degree (Table 53.3). Instability is characterized by a sensation of ‘giving way’ during unexpected movements under load. There may be accompanying pain and discomfort, sometimes lasting for a day or two. Additional instability tests will usually detect the type and degree of ligamentous insufficiency (see online chapter Disorders of the inert structures: ligamentous instability). Experimental studies over the past few decades have demonstrated that regeneration of injured connective tissue is significantly better with the application of continuous passive motion. Under functional load, the collagen fibres are oriented in a longitudinal direction and the mechanical properties are optimized.6 Therefore, functional conservative treatment is advised for all coronary ligament sprains and all isolated grade I, II or III sprains of the medial collateral ligament7 and posterior cruciate ligament and isolated grade I or II lesions of the anterior cruciate ligament.8 However, in combined lesions and in anterior cruciate ligament tears with a positive pivot shift phenomenon, surgery is the treatment of choice.9 Mobilization not only is the best promoter of ligamentous repair but also prevents ligamentous adhesions within or around the healing structure. Another advantage of early mobilization is the positive effect on muscle strength10 and proprioceptive reflexes,11 which ensures the active stability of the joint. This conservative and functional approach to recent and isolated tears was first advocated by Cyriax12 and has recently received much support. Several studies have demonstrated that the non-operative management of an isolated medial collateral ligament injury, especially of grade I and II, is as good as, if not better than, a primary surgical approach.13–18 The conservative treatment of grade III sprains of the medial collateral ligaments also gives results that are equally as good as the surgical approach but with significantly quicker rehabilitation.19–21 Jones et al22 treated 24 high-school football players with an isolated grade III injury of the medial collateral ligament. They administered mobilization, using a regime of muscle strengthening and agility exercises. Knee stability was achieved in 22 cases, with an average recovery time of 29 days. The players returned to competitive sport after a mean of 34 days. Similar results were obtained in a long-term study of 21 grade III medial collateral ligament tears.23 The overall conclusion was that non-surgical treatment of a complete tear of the medial collateral ligament was extremely successful, provided there was no associated structural damage to the anterior cruciate ligament. • Relieve the inflammation and pain as soon as possible so the patient can mobilize the knee. This can be achieved by local infiltration of a small amount of triamcinolone. • As advised by Cyriax, mobilize the ligament over the bone by deep transverse friction instead of moving the bone under the ligament as in ordinary mobilizations. The relative movement will be the same, as is the mechanical stimulus to the regenerating fibrils. The medial collateral ligament prevents valgus deviation of the knee and, through its posterior fibres, checks external rotation of the tibia.24 An understanding of this is of importance in the interpretation of clinical tests in a torn medial collateral ligament.25 The medial collateral ligament is the most commonly injured ligamentous structure of the knee. The classic mechanism of injury is a forced valgus movement on a partly flexed and externally rotated knee,26 which typically occurs when a soccer or American football player receives a kick or blow at the outer side of the weight-bearing knee.27 The patient experiences a crack and feels sudden pain at the inner aspect of the knee. Most of the pain disappears fairly quickly and the sportsman or woman can probably return to the game or walk off the pitch. At first, the knee is not swollen and there is only slight disability. The real incapacity, with increasing swelling and pain, starts after a few hours. By the next day, the patient can hardly stand and can only hobble with assistance. The tear can be proximal, be related to the mid-portion of the ligament or be situated at the distal, tibial portion (Fig. 53.2). Mid-portion tears are the most common, but also the most disruptive, because they also involve the deeply situated meniscotibial and meniscofemoral portions of the ligament.28 In a proximal tear, it is wise to perform radiography to exclude avulsion of a bony fragment, which is an indication for surgical repair.29,30 • There has been good healing, with a strong non-adherent ligament. • The ligament is permanently lengthened, resulting in an unstable knee. • The ligament is adherent, leaving the patient with recurrent and localized disability. Sometimes calcification of the medial collateral ligament develops after an apparently ordinary sprain of the inner side of the knee. Suspicion arises when increasing limitation of flexion, together with a hard end-feel, is found 4–6 weeks after the accident. Radiography shows ossification along the inner side of the medial femoral condyle.31 Conservative treatment is ineffective but good results have been reported with surgical treatment.32 Spontaneous recovery takes 6 months to 1 year.33 All grade I and grade II sprains (partial tears), as well as isolated grade III sprains (complete tears) of the medial collateral ligament should be treated conservatively. Surgery is indicated only in combined lesions of medial collateral ligament and meniscus and/or anterior cruciate ligament.34 The technique chosen depends on the stage of the lesion, as summarized in Box 53.2. If the patient is seen during the first 24 hours after the accident, local infiltration with triamcinolone can be considered. Deep transverse friction in combination with early mobilization can be applied during the first 6 weeks following the accident. If the patient is seen after more than 6 weeks, the lesion must be considered as chronic and manipulation is given. During the next 24 hours, the patient remains in bed with an ice bag on the affected area. From the second day on, flexion is strongly encouraged, as is extension without weight bearing. During the first week, however, no attempt should be made to straighten the knee completely on walking; the medial collateral ligament is taut in extension and too much stretching at the point of injury would cause harm. On account of the anti-inflammatory effect of the triamcinolone, pain and swelling abate very quickly and normal gait is restored after 1–2 weeks. Walking and modest movement of the knee should be encouraged because they provide the best stimulus to normal healing and prevent the formation of adhesions. The patient can usually return to sports after 6 weeks.35 By that time, movements are of full range and ligamentous tests negative. It is wise to recommend a protective knee brace during the first few weeks of sporting activity, especially if the patient returns to contact sports. The patient lies supine, with a pillow under the knee. The physician, standing at the inner side of the knee, outlines the correct area. A fine needle is fitted to the syringe, filled with a mixture of 1 mL of lidocaine 2% and 20 mg of triamcinolone. The needle is thrust in almost horizontally (Fig. 53.3) and the whole tender area is infiltrated by a series of small droplets. Friction serves a double purpose: it prevents any fibrils from binding the ligament to bone and applies a positive stimulus to the healing connective tissue. As, in the acute stage, adhesions will not yet have formed, just 2 minutes of deep friction are required in both flexion and extension, though the preparatory phase of gentle massage, followed by slight superficial friction (which renders the ligament anaesthetized), may take up to 20 minutes. The patient is given this deep friction every day during the first week, after which the subacute stage is entered. If the massage is given adequately, the range of flexion increases dramatically during the first few days. The patient should be encouraged to walk and to move actively, although straightening the last 20° or flexing the last 60° must be avoided during the first week because these movements put too much longitudinal strain on the ligament.36 The joint can be protected with a partial mobile brace, the coronal straps of which prevent excessive valgus movement.37

Disorders of the inert structures

Ligaments

Introduction

Classification

Severity

Structure

Time

Grade I: slight overstretching

Isolated sprain

Acute: less than 2 weeks

Grade II: partial tear

Combined sprains

Subacute: between 2 and 6 weeks

Grade III: complete tear

In combination with meniscal tears

Chronic: more than 6 weeks

Diagnosis

History

Examination

Acute ligamentous lesions

Serious lesions

Less serious lesions

Impairment of function

Immediate inability to continue the sport or activity

Most initial pain disappears and sports and activities can be continued after a short time

Swelling

Immediate or developing during the first hour, indicating haemarthrosis5

Appears a few hours after the accident, with functional incapacity and generalized pain

Feeling of instability?

Yes

No

Aspiration

Blood may be present

Clear fluid is obtained

Possible diagnoses

Triad of O’Donoghue?

Isolated rupture of a cruciate ligament?

Isolated sprain of a collateral, coronary or cruciate ligament

Chronic ligamentous lesions

Treatment: the principle of early mobilization

Isolated sprains

Medial collateral ligament

Diagnosis

Stieda–Pellegrini disease

Treatment

Acute stage

Infiltration and cold compression

Technique: infiltration

![]()

Friction