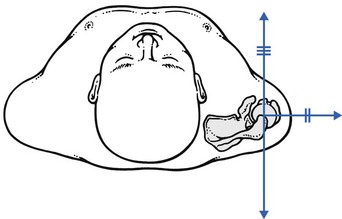

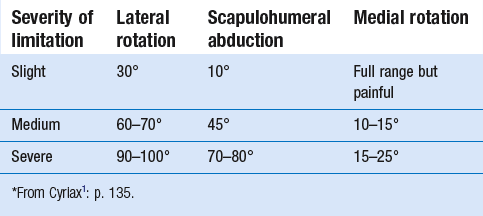

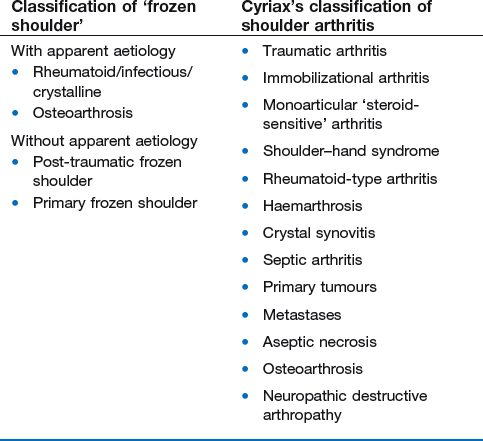

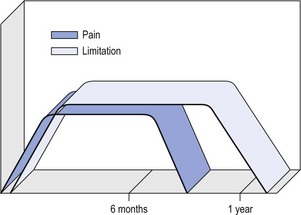

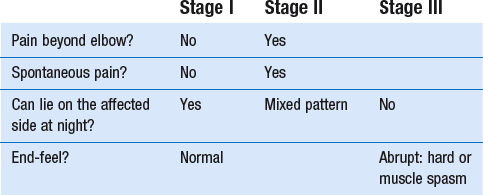

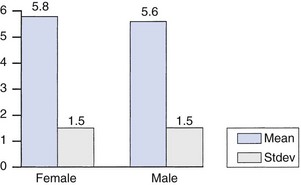

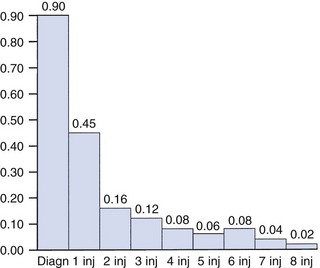

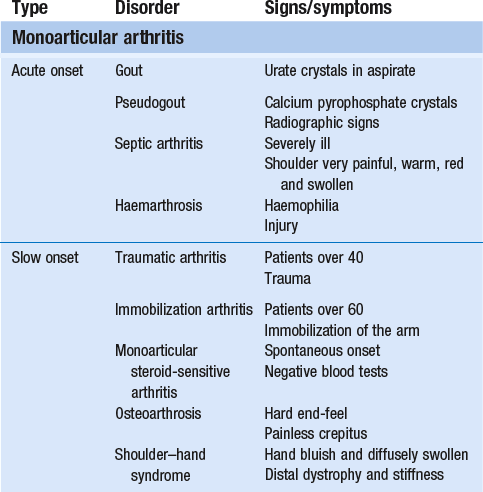

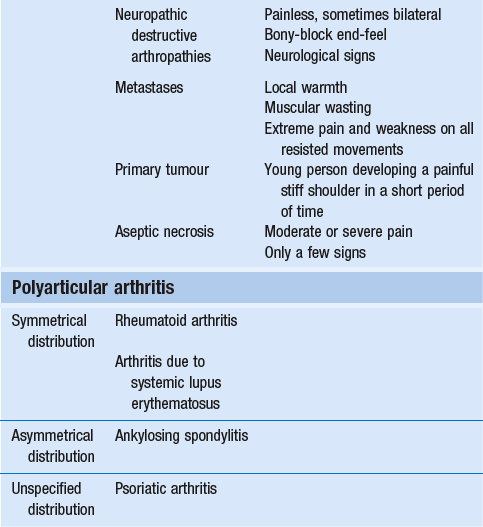

14 The capsular pattern at the shoulder joint is a proportional limitation of the three passive scapulohumeral movements. There is some limitation of abduction, more limitation of external rotation and less limitation of internal rotation.1,2 A capsular pattern always indicates a lesion of the capsule of the joint, whatever its nature may be.3 It may be either an acute synovitis or a chronic organized reaction of the fibrous capsule. In an acute inflammation of the synovia, the selective limitation of movement is caused by involuntary muscle spasm that protects the inflamed joint from further overstretching. In long-standing inflammation of the capsule, structural changes have set in. Intracapsular fibrosis and thickening of the capsule now cause mechanical obstruction of the movements. Several arthrographic4,5 and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies6–9 have demonstrated that these adhesions form mainly at the axilla and the anterior portion of the capsule. This greater loss of inferior and anterior capsular elasticity explains the greater restriction of lateral rotation and abduction (the capsular pattern) (Fig. 14.1). The degree of the limitation is expressed in its magnitude; limitation can be slight, medium or gross, although it is always in the same (articular) proportion (Table 14.1). The stage is a clinical estimation of the severity of synovial inflammation. The staging is based on four clinical criteria: pain at rest, nocturnal pain, the distal reference of the pain and the end-feel (Box 14.1). Three stages are considered. Stage I corresponds to a minor degree of inflammation: there is no pain at rest and no nocturnal pain, the pain does not spread beyond the elbow and the end-feel shows no protective muscle contraction. Stage III is the worst: the highly inflamed synovia leads to pain at rest and at night, the pain spreads beyond the elbow, and the end-feel shows protective muscle spasm. From a therapeutic point of view, stage is more important than degree of limitation, especially in post-traumatic arthritis and immobilizational arthritis. The phase situates the arthritis on the timeline of the natural history. Classically three phases are considered: the painful phase, the progressive stiffening phase and the thawing phase (see p. 223). Stiffness of the glenohumeral joint has classically been called ‘frozen shoulder’.10 Several investigators have attempted to propose a nomenclature to separate different types of shoulder stiffness.11–13 The subgroup typing was based on both the severity of stiffness and the presence or absence of an associated cause. The group without an apparent background was further subdivided into either ‘post-traumatic frozen shoulder’, where an injury or a surgical intervention was at the root of the disorder, and ‘primary frozen shoulder’, where no causative precursor could be found.14 Cyriax1 listed 13 different disorders leading to ‘shoulder stiffness’ with a capsular pattern (Box 14.2). • Try to detect an intrinsic aetiology, which may be either a general disease (rheumatoid type of arthritis) or a local condition: infection, gout, haemarthrosis or tumour. • In the remaining subgroup where no intrinsic aetiology can be found and the only finding is of a progressive stiffening of the capsule, history will indicate whether the arthritis should be called post-traumatic, post-immobilization or primary. A capsular pattern may develop after glenohumeral (sub)luxations, contusions or surgical procedures to the shoulder.15 Most often, however, injury need not have been severe and a traumatic arthritis may precipitate some days after the shoulder capsule sustained an indirect and sudden traction or, for example, after the joint bumped against a wall. Because it can take some weeks for the pain to become bad enough to force the patient to consult a physician, it is quite possible that such a minor accident may have been forgotten. The evolution and natural history of traumatic arthritis are quite typical. It takes about a year for the lesion to heal spontaneously. During this process, three stages of about 4 months each are observed (Fig. 14.2).16 In the first, ‘painful phase’, both pain and limitation of movement increase. In the second, ‘progressive stiffness phase’, pain diminishes but limitation remains the same. It is not until the beginning of the last 4 months that limitation begins to decrease (the resolution or ‘thawing’ phase), so that by one year movement is back to normal.17 Several authors, however, have demonstrated a significant number of patients with a delayed thawing phase and one instance showed persistent stiffness for 6 years.18–20 Sometimes elevation and lateral rotation may remain slightly restricted permanently.21 The final stage of the natural evolution is the resolution or the thawing phase, characterized by a slow and gradual gain in mobility. Usually a few months (4–6) may be required to achieve full functional motion. The joint is in stage III with moderate pain and a hard ligamentous end-feel.22 The choice of treatment for post-traumatic arthritis should always be adjusted according to the duration and severity of symptoms. Treatment techniques should also be applied in the context of the patient’s needs, risk factors and tolerance. Finally, the outcome of the treatment must always be related to the expected natural history of the disease, and treatment is only begun when it is expected to change the course of this natural history positively.23,24 If arthritis has set in, it is too late for prevention and treatment to the capsule should be given. Gentle but firm passive stretching exercises have proven effective in the relief of pain and recovery of range in motion in up to 90% of patients with capsular stiffness.25–30 However, some studies report inadequate results with stretching and even exacerbation of the condition.31,32 Before capsular stretching is begun, analgesic short-wave diathermy can be given for 10 minutes. The patient lies supine and brings the ipsilateral hand on to the forehead. The therapist stands on the same side, facing the patient, and puts one hand on the sternum and the other on the elbow of the affected side. By pushing the elbow backwards towards the couch, the capsule of the joint is stretched (Fig. 14.3). In this way the inferior recess of the capsule, where most of the adhesions lie, is elongated. The hand on the sternum prevents the patient from curving the trunk to avoid the stretch. The capsular stretching is done in elevation. As this is a combined movement, the rotations improve simultaneously with the increase in abduction range. If this does not happen, the shoulder must be stretched in lateral rotation as well. Stretching is continued until the shoulder is back to normal (pain and range) or no further gain is achieved. The results are good, and passive capsular stretching has been proven to be a fast and safe mode of treatment for ‘adhesive capsulitis’ in stage I or IIa arthritis.33–35 This technique consists of very gentle elongation of the joint capsule performed in such a way that the fibres are stretched longitudinally. It has been suggested that this inhibits nociceptive reflexes which result from long-standing stimulation of the nocisensors. These reflexes would be responsible for increased sympathetic activity giving rise to vasoconstriction of the vessels around the joint.36 The patient lies supine, the arm along the side, with a small cushion beneath it for maximum comfort. The therapist sits at the patient’s painful side and brings the ipsilateral hand deep into the axilla, the other one partially on the outer aspect of the shoulder, partially reinforcing the one in the axilla (Fig. 14.4). The ipsilateral hand will try to pull the head of the humerus out of the glenoid fossa. The direction of the pull is mainly lateral and slightly cranial and anterior. Manipulation under anaesthesia has been used for over a century. Some believe in its effectiveness,36–38 while others have denounced its use because they think there is no change in the time course of the disease after the manipulation or they have seen too many complications. Ruptures of the subscapularis tendon, damage to the neurovascular structures, and fractures and dislocations have been reported after manipulation under anaesthesia.39–43 That the method can cause iatrogenic damage was recently demonstrated by an arthroscopic study.44 After manipulation, the anterior portion of the capsule was seen to be ruptured in 75% of the patients. Iatrogenic superior labrum lesions were observed in 15%, fresh partial tears of the subscapularis tendon in 10% and anterior labral detachments in 15%. In an attempt to suppress the painful inflammatory response in post-traumatic capsulitis of the shoulder, intra-articular injections with corticosteroids have been used for decades. Studies that evaluate the response to intra-articular injections generally combine the injection with other treatment methods and rarely compare the efficacy of the injection alone. However, some studies could demonstrate improvement in pain scores and increase in range of motion after steroid injections alone.45–49 Other investigators are very sceptical about the injections as their studies failed to demonstrate the benefit of the treatment.50 Cyriax could not initially find benefit in intra-articular hydrocortisone injections51 but after he detected the advantages of a sequence of consecutive intra-articular injections with triamcinolone, he became a very enthusiastic advocate of intra-articular injections for capsulitis of the shoulder.52 The coracoid process is palpated in the infraclavicular fossa. The examiner puts the index finger here and places the thumb dorsally on the posterior angle where the scapular spine meets the acromion. A 4 cm needle is fitted on a 2 mL syringe filled with 20 mg of triamcinolone. It is inserted just below the thumb and aimed at the coracoid process. The same approach is used nowadays for arthroscopy via the posterior portal.53,54 After about 2–3 cm the needle is stopped by the articular surface of the head of the humerus and there is a typical cartilaginous sensation. At this point, the needle lies intra-articularly. Just before the needle is arrested, tough resistance is felt on passing through the capsule (Fig. 14.5). A practical scheme, with increasing intervals between the injections, is as follows: • Second: after 1 week: day 7. • Third: 10 days after the second injection: day 17. • Fourth: 2 weeks after the third one: day 31. • Fifth: 3 weeks later: day 52. • Sixth: 4 weeks later: day 80. • Seventh: 5 weeks later: day 115. • Eighth: 6 weeks later: day 157. A summary of the treatment of traumatic arthritis is shown in Figure 14.6. Hydrodilatation, sometimes referred to as distension arthrography, has been proposed as a therapeutic procedure for glenohumeral joint contracture.55 It is proposed that its benefits are derived from a combination of the anti-inflammatory effect of cortisone with the mechanical effect of joint distension, thereby reducing the stretch on pain receptors in the glenohumeral joint capsule and its periosteal attachments.56 Hydrodilatation was first used in 1965 by Andren and Lundberg,57 who reported variable results ranging from extremely effective to extremely painful. More recent studies have also cited variable results.58–60 Several double-blind, prospective studies could not detect any significant differences between a regimen of hydrodilatation that included steroids compared with steroid injections alone.61–64 As with manipulation under anaesthesia, this technique should be reserved for those few cases that do not respond to passive mobilization and injection with corticosteroids. Recent studies have demonstrated that arthroscopic capsulotomy may be an effective technique in the management of the frozen shoulder that does not respond to physiotherapy.65–68 During standard shoulder arthroscopy, intra-articular cautery is used for complete division of the anterior–inferior capsule, the intra-articular portion of the subscapularis tendon and the middle glenohumeral, the superior glenohumeral and the coracohumeral ligaments.69 In patients over 60, when the shoulder is immobilized, it is at risk of becoming stiff. The reasons for the initial immobilization may be multiple. Immobilizational arthritis is a well-known complication in hemiplegics.70–73 During a prospective study, conducted by Bruckner and Nye, 25% of patients with subarachnoid bleeding developed a frozen shoulder over an observation period of 6 months.74 Other neurological conditions such as Parkinson’s disease may precipitate capsular stiffening.75,76 Immobilization of the arm for disorders such as a fracture of the elbow or the humerus is also reason enough to develop a post-traumatic arthritis.77 For many years clinicians have associated ischaemic heart disease and shoulder arthritis,78 which eventually develops as the result of immobilization after an infarction or surgery. This condition should never be encountered. It is very important for primary care physicians and physiotherapists to realize that immobilized shoulders should be given gentle movements at least once a day, in order to prevent the development of an immobilizational shoulder arthritis. This simple advice was already given by Neviaser, who in 1945 wrote: ‘I believe we can accept the fact that disuse and inactivity play a very important role in the etiology.’79 In prevention, it is sufficient to maintain the normal range of movement from the very beginning of immobilization. If arthritis has set in by the time the patient is first seen, it should be managed in the same way as traumatic arthritis: stage I is treated with capsular stretching, stage III with a series of intra-articular injections of 20 mg of triamcinolone. Stage IIa can also be treated with stretching if the end-feel is right. If this is not the case, the patient should receive intra-articular injections. A monoarticular arthritis that develops without apparent cause – neither trauma nor immobilization can be traced in the history – is called ‘idiopathic frozen shoulder’80 or monoarticular ‘steroid-sensitive’ arthritis. The latter term comes from Cyriax, who discovered that most cases of ‘freezing arthritis’ could be successfully treated with a series of intra-articular steroid injections.81 Although the exact cause of the capsular inflammation and the subsequent capsular fibrosis is not exactly known, recent investigators have focused on the inflammatory cellular changes and immunological response in the synovium and the capsule. Currently it is not known exactly what triggers the initial synovial inflammation. Some point to specific cytokines which may be involved in the early inflammatory stages of the disease.82 Several references in the literature assume frozen shoulder to be an algoneurodystrophic process.83,84 Others suggest that a proteinase may be involved in the pathogenesis of both a Dupuytren’s contracture and a frozen shoulder.85,86 Others have suggested that an area of focal necrosis in a degenerative tendon is the earliest lesion, followed later by a generalized chronic inflammatory reaction of the whole capsule and of the rotator cuff.87 Hannafin and colleagues have studied the histopathologic evolution of monoarticular shoulder arthritis. They found an initial hypervascular synovitis, provoking a progressive fibroblastic response in the adjacent capsule, finally leading to diffuse capsular fibroplasia, thickening and contracture.88 The bulk of patients who present with primary monoarticular arthritis of the shoulder are between 45 and 60 years of age,77,89 although the disease can be encountered at any age.90 Approximately 70% of patients presenting with adhesive capsulitis are women.91 The overall prevalence of the disorder is about 2%. In diabetics the figure is almost 11%.92,93 Other studies show diabetes to be present in 25–38% of the patients suffering from adhesive capsulitis.94,95 Some connection with hyper- or hypothyroidism has also been suggested, although the link between the disorders remains obscure.96 Recently adhesive capsulitis has also been described in patients treated with highly active antiretroviral drugs.97,98 The onset is spontaneous and involves only one shoulder at a time; sometimes the other shoulder may become involved within 5 years.99 In the spontaneous evolution of a monoarticular steroid-sensitive arthritis, four periods of about 6–9 months each are distinguished (Fig. 14.7).100 Initially, the patient starts to feel pain at the shoulder for no apparent reason. This increases progressively, becomes continuous (although often worst at night) and starts to spread beyond the elbow. It causes many months of sleepless nights, a more than sufficient reason to start treatment at once. At the same time movement becomes progressively limited. During the second phase, the pain gets no worse but remains maximal for another 6 months. Limitation does not change for about 12 months. One year (sometimes even more) after the onset, the pain starts to diminish and it disappears almost fully at the end of this third phase. Restriction of movement, however, does not alter. Finally, in the fourth period, the limitation of movement gradually decreases. At this time, only some slight discomfort and a certain degree of stiffness remain, which usually disappear fully at the end of the 2 years. Exceptionally, a few degrees of restriction of elevation will be permanent.101,102 These clinical phases in the natural history of idiopathic capsulitis of the shoulder correspond roughly with the histopathologic phases identified by Hannafin:88,103 first hypervascularization and inflammation of the synovia (first period), then progressive fibroblastic response of the capsule (second and third periods), and finally the remodelling of the capsule (fourth period). Both pain and limitation remain maximal during the entire second phase. During the final (‘thawing’) phase, the range of movement progressively increases to return to normal about 2 years after the onset. Some authors have stated, however, that it may take longer for the stiffness to disappear completely or that some degree of stiffness may remain.104 In general, the duration of the recovery stage is related to the duration of the stiffness phase: the longer the stiffness phase, the longer the recovery phase.105 As in traumatic arthritis, three stages are distinguished in relation to the degree of inflammation (see p. 222): stage I is the slightest, while stage III is the worst (Table 14.2). The stages are based on the following criteria: Because spontaneous recovery takes about 2 years and the patient suffers severely in the meantime, treatment is absolutely necessary.106,107 As a rule, a series of intra-articular injections with triamcinolone are given, whatever the stage of the arthritis. Exceptionally, capsular distraction is used for those patients who do not want injections or when steroids are contraindicated. If distraction is used, it should be performed in the same way, frequency and duration as for traumatic arthritis (see p. 225). Injections for monoarticular steroid-sensitive arthritis are given in the same way (technique and interval) as for traumatic arthritis (see p. 226). They can be stopped once the patient can use the arm freely, the end-feel is back to normal and no relapse of pain occurs by 6 weeks after the previous injection. If some limitation of movement still exists by then, it usually disappears spontaneously during the following months. It is rare for patients not to respond to injection therapy or to remain with a painless stiff shoulder.108 In 1989 we did a prospective study on 54 patients with idiopathic arthritis of the shoulder. The youngest patient was 40, the oldest 71. On clinical examination all showed a clear capsular pattern and none had pain on any resisted movement. Laboratory tests were performed to exclude other rheumatoid types of arthritis and to check for a possible association with diabetes (only one diabetic patient was identified). Over 90% of the cases presented initially with stage II or stage III arthritis. All were treated by a series of intra-articular injections given at increasing intervals. The total number of injections given was between four and nine with an average of six (Fig. 14.8). After the first injection half the patients were less troubled at night. This figure increased to more than 90% after the third injection. Spontaneous pain decreased in the same way as the nocturnal pain but with some delay, being less severe and progressively less distantly referred. After eight injections, 98% of all patients had no pain (Fig. 14.9). The range of movement of rotation and elevations began to increase after the first injection, though this was not very obvious clinically. An increased amplitude usually became clear after the third injection. The final conclusion of the study was that 98% of all patients recovered fully from their pain – only one patient continued to have a painful shoulder. There was an 80% increase in range of movement after the seventh injection. The results of this study correspond roughly with what was found by others.87,109 Shoulder–hand syndrome, first described in the 1950s, is a relatively rare clinical entity classified as a complex regional pain syndrome type 1 (CRPS1), or ‘reflex sympathetic dystrophy’.110 The condition consists essentially of a painful ‘frozen shoulder’ in combination with disability, swelling, and vasomotor or dystrophic changes in the ipsilateral hand. At onset, the hand is bluish and diffusely swollen. Later the wrist and fingers become stiffened (flexion contracture with limitation of extension) and the skin shiny and atrophic.111 The shoulder involvement usually precedes, sometimes accompanies or rarely follows the changes in the hand. The pathophysiology is not completely clear but a predominant ‘sympathetic’ factor affecting the neural and vascular supply to the affected parts seems to be involved.112,113 Cyriax considered the syndrome to be a type of monoarticular steroid-sensitive arthritis.114 So far the exact cause has not been clarified, although some assume that emotional instability could be an important factor. The arthritis is treated in the same way as any other steroid-sensitive arthritis Conventional radiography remains the standard imaging technique for joint studies in patients with suspected RA. The first radiological signs are osteoporosis and joint space narrowing. Later chondral erosions and small bone erosions at the joint margin are seen. Marginal and central erosions follow in advanced stages. Fibrous ankylosis, joint deformities (subluxations and dislocations), fractures and fragmentations are typical findings of more advanced RA.115–117 RA is best treated systemically; local intra-articular injections are used only as a secondary aid. Sometimes the shoulder is the seat of a reactive type of arthritis in which the inflammation is caused by an infection but in which no bacterial or viral agent can be isolated from the synovial fluid.118 Ankylosing spondylitis rarely starts in the peripheral joints but cases have been described with initial localization at shoulder or hip.119,120 Particularly in the paediatric form of the disease (juvenile ankylosing spondylitis), peripheral joint involvement is more frequent and can precede, by many years, the onset of back features.121 In its later course, signs and symptoms will be more localized in the spine and the sacroiliac joints. Arthritis at the shoulder from this disorder responds well to intra-articular steroids. The pain disappears fully but very often movement remains limited. A patient complaining of severe pain immediately after an injury and showing a capsular pattern should always be suspected of having a haemarthrosis. In haemophilia, the haemarthrosis can develop spontaneously. It is more common at knee, elbow and ankle joints than in the shoulder.122 Blood is very irritant to articular cartilage and so should be aspirated at once. If it is not, it will lead to full destruction of the joint over a the course of a few years.123 Crystal synovitis at the shoulder from urate crystals (gout) is very rare.124 This disorder should be considered when a capsular pattern comes on spontaneously in a few hours. It normally remains monoarticular but has often been preceded by earlier attacks in smaller joints (particularly in the metatarsophalangeal joint of the big toe). It disappears spontaneously in the course of a week and responds very well to colchicines or phenylbutazone. Diagnosis is mainly based on the presence of urate crystals in the synovial fluid.125 Pseudogout is the result of the presence of pyrophosphate crystals in the joint. The term ‘chondrocalcinosis’ is used if calcification in the hyaline cartilage of the joint is visible on radiography.126 The knee is much more commonly affected than the shoulder.127 Clinically, the presentation is spontaneous but is less acute in onset than gout. Crystals are also present in the synovial fluid and can be detected by high-resolution sonography.128 Pseudogout resolves spontaneously in about 3–4 weeks. Septic arthritis can be provoked by direct inoculation of a bacterium into the joint, by haematogenous dissemination or from adjacent osteomyelitis. It is mainly seen in elderly people, often in connection with other predisposing factors such as diabetes, immune deficiency, malnutrition and alcoholism.129,130 Some cases occur after mastectomy and radiotherapy for breast cancer.131 A joint affected by a chronic arthritis, such as rheumatoid arthritis, is more likely to develop septic arthritis. It rarely occurs in the healthy elderly or in young adults. In children it may be a sequel to adjacent osteomyelitis. Acute septic arthritis may also present as an iatrogenic infection following joint arthroscopy, joint aspiration or local corticosteroid joint injection.132–134 In many cases Staphylococcus aureus is the causative agent.135 Sometimes a streptococcus or Escherichia coli is present, and even a gonococcal infection may be found. Inspection may show a swelling, which is often due to a subcutaneous abscess that communicates with the joint. On testing the shoulder, a very pronounced capsular pattern is found. In the initial stage, radiology is diagnostically irrelevant. As the condition develops further, periarticular osteoporosis, diminution of the joint space and finally joint destruction are found. Biological features, such as raised erythrocyte sedimentation rate and increased leukocyte counts, are suggestive but not confirmative. A diagnostic (and evacuating) aspiration of the joint, with a wide-bore needle (> 20 gauge), usually shows over 100 000 leukocytes/mm3, more than 90% being of the polymorphonuclear type. Sometimes the bacterial agent can be isolated.136 Septic arthritis of the shoulder is more difficult to treat than septic arthritis at any other joint. It is a very severe disorder and death is not uncommon.137 The condition is normally managed with systemic antibiotics and daily evacuation of the pus. Also the combination of arthroscopic irrigation debridement and systemic antibiotic therapy is often used.138 Sometimes open surgical drainage is necessary. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate is a useful monitor of adequate treatment.139 Very often the long-term result is significant limitation of movement at the glenohumeral joint because of bone destruction. Primary tumours at the shoulder are mainly encountered in the young and may occur in acute leukaemia140 or be due to sarcoma.141 The tumour often presents insidiously. In the beginning it is characterized by localized, non-mechanical pain. From the moment that the tumour incites a synovial response, a painful capsular pattern at the shoulder will gradually develop.142,143 In a younger patient, this should always arouse the suspicion of a primary tumour. Even the slightest limitation in a young patient is a formal indication for further careful exploration of this area by techniques such as radiography, computed tomography (CT) or MRI. Localized warmth is usually the first sign, later followed by a very pronounced capsular pattern, with much pain and limitation because both joint and muscles are affected.144 Moreover, the resisted movements are extremely weak and painful. Visible muscular wasting is present. A radiograph or a bone scan can help confirm the diagnosis. As in the hip, osteonecrosis of the shoulder results from disruption of the osseous arterial inflow or the venous outflow. The cause is either traumatic (fractures of the proximal humerus have been associated with an osteonecrosis rate ranging from 15 to 30%),145 non-traumatic or idiopathic. Non-traumatic cases may be the result of haemoglobinopathies,146 radiation of the joint or diving accidents.147 High doses of systemic corticosteroids represent the most commonly reported iatrogenic cause of osteonecrosis.148,149 Often, the initial signs and symptoms are subtle and may include vague diffuse shoulder pain and difficulty sleeping. This pain deteriorates with disease progression and may be tolerable until the later stages. Determining the presence of risk factors for osteonecrosis, including prior steroid exposure, other medical conditions or alcohol abuse, may sometimes provide the only clue to the disease. Also, the patient’s age at presentation may offer a hint, as these patients are generally younger than those with primary osteoarthritis.150 The clinical picture, particularly early in the disease process, may be that of a slight capsular pattern. Also symptoms of locking, popping or a painful click may indicate the presence of loose osteochondral fragments.151 With disease progression, significant limitations in motion of a non-capsular type – secondary to joint incongruity – and an increase in pain will become more evident. Technetium bone scanning and MRI can detect aseptic necrosis in the early stage.152,153 Later on, the whole joint is destroyed and the disease can be visualized on plain radiography. Treatment consists of core decompression in the early cases.154,155 In very severe cases, shoulder arthroplasty may be indicated.156 A number of different processes can destroy the glenohumeral joint surface. If no apparent reason for the development of osteoarthrosis can be found, it is termed primary degenerative joint disease. This is characterized by a triad of anterior capsular contracture, posterior wear of glenoid and subchondral bone, and posterior humeral subluxation.157 Primary arthrosis does not usually evoke much pain. Indeed, a patient with an arthrotic shoulder, in the absence of any capsular inflammation, complains merely of painless crepitus on movement. During and after exertion there may be a vague ache, which usually disappears after a few hours. There is a capsular pattern with a hard but almost painless end-feel. With shoulder movement, crepitus may be detected on palpation. However, an osteoarthrotic joint is much more liable to develop arthritis, which can be the result of only a slight injury or some unusual activity. Once arthritis has set in, the limited movements also become painful. The diagnosis of primary arthrosis at the shoulder should be made on clinical grounds and should not be based solely on the radiograph, as it is quite possible to have no arthrosis on clinical examination but signs of it present on the radiograph. In contrast, secondary degenerative joint disease may be much more painful and disabling. It occurs when previous injury, surgery or another condition affects the joint surface and causes degeneration. Chronic glenohumeral subluxations often lead to severe osteoarthrosis. The condition also develops when a chronic and massive tear of the rotator cuff subjects the uncovered humeral articular cartilage to compression against the undersurface of the coracoacromial arch. The resulting arthrosis is then called ‘cuff arthropathy’.158 In this case, clinical examination will reveal total rupture of the supraspinatus in combination with limited movement in a capsular way. Also, in the end-stage of avascular necrosis of the shoulder, the irregular head destroys glenoid articular cartilage, which results in secondary degenerative joint disease.159 Neuropathic osteoarthropathy, also known as Charcot neuroarthropathy, is a chronic, degenerative arthropathy and is associated with decreased sensory innervation.160 There are numerous causes of neuropathic osteoarthropathy, the three most common being diabetes, syphilis and syringomyelia. Diabetic patients tend to have involvement of the joints of the foot and ankle, whereas larger joints such as the knee are commonly affected in patients with syphilis. Patients with syringomyelia tend toward involvement of the shoulder and elbow.161 Syringomyelia is a disorder involving a fluid-containing cavity (syrinx) within the spinal cord. These cavities commonly occur in the lower cervical and upper thoracic segments, and the distension may propagate proximally. Syringomyelia may have congenital, traumatic, infectious, degenerative, vascular or tumour-related causes.162,163 The joint and the subchondral bone are destroyed because of the loss of the trophic and protective effects of its nerve supply. In neuropathic destructive arthropathy, a gross but painless capsular pattern with a very hard bone-to-bone end-feel is found. The complete clinical picture is slow to develop. By the time the painless capsular pattern and bony end-feel are found, the underlying condition is usually already known from other neurological signs, such as muscular weakness and atrophy in the upper limbs occurring over a short period. Radiography provides the key to the diagnosis.164 Table 14.3 summarizes shoulder lesions that present with a capsular pattern.

Disorders of the inert structures

Limited range of movement

Capsular pattern

Introduction

Staging

Conditions

Traumatic arthritis

Natural history

Thawing phase

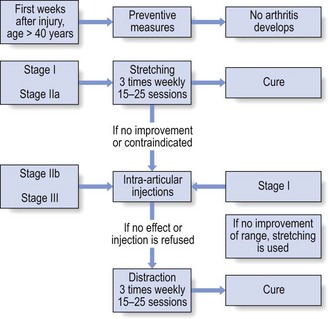

Treatment

Passive movements

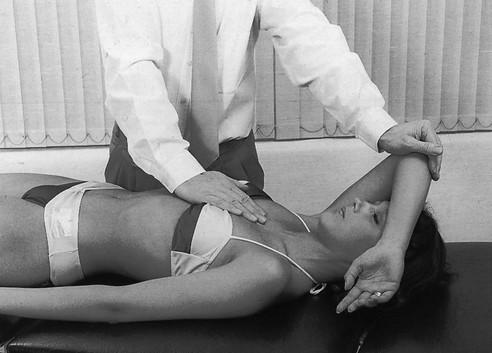

Capsular stretching

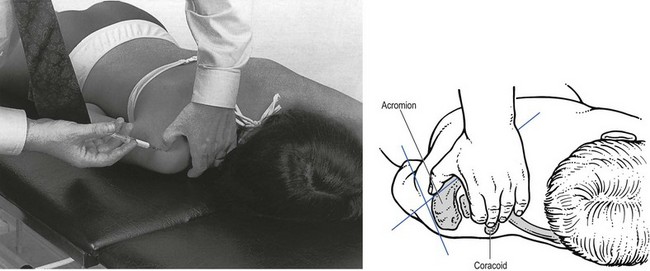

Distraction

Manipulation under anaesthesia

Intra-articular injections

Other treatments

Immobilizational arthritis

Treatment

Monoarticular ‘steroid-sensitive’ arthritis

Pathophysiology

Incidence

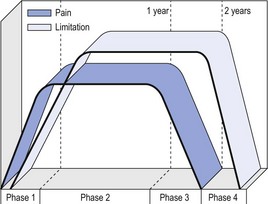

Natural history

Functional examination

Staging

Treatment

Shoulder–hand syndrome

Rheumatoid-type arthritis

Haemarthrosis

Crystal synovitis

Septic arthritis

Septic non-tuberculous arthritis

Treatment and prognosis

Primary tumours

Metastases

Aseptic necrosis

Osteoarthrosis

Neuropathic destructive arthropathy

Disorders of the inert structures