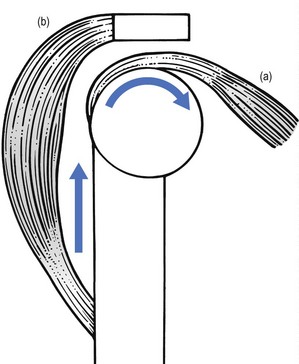

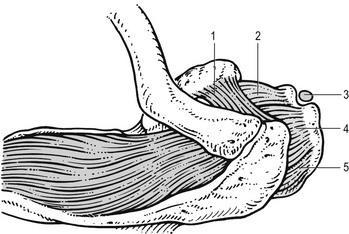

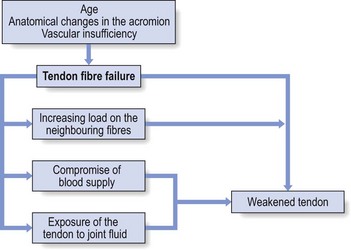

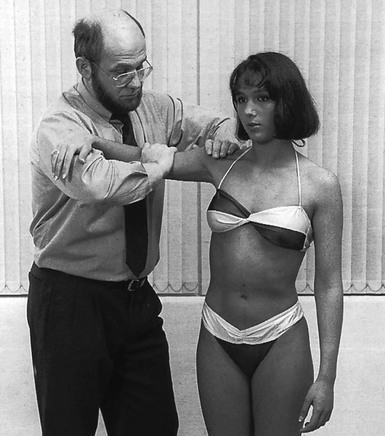

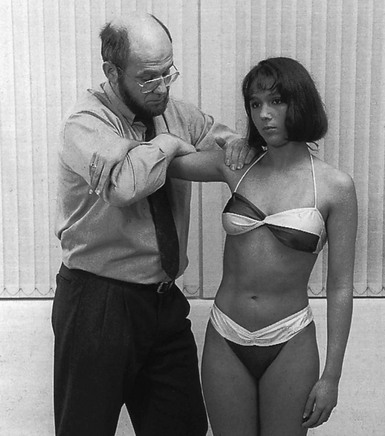

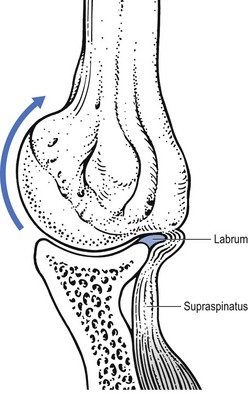

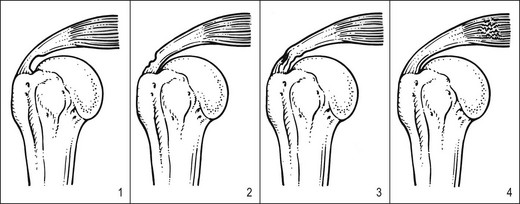

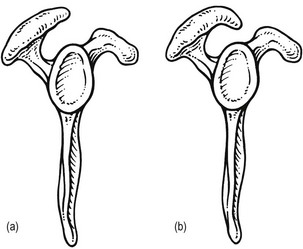

15 Functionally, shoulder muscles are of two types: stabilizing muscles and effector muscles. Stabilizing muscles (A, Fig. 15.1) are relatively small, with insertion tendons that lie close to, or even in, the substance of the fibrous capsule. Therefore they are not capable of causing significant shoulder movement but rather maintain the humeral head in the glenoid fossa. These stabilizing muscles are called the rotator cuff and include supra- and infraspinatus, teres minor and subscapularis. They all originate from the scapula, run partly under the acromial roof and insert on the humeral tubercles. Effector muscles (B, Fig. 15.1) are much larger, with tendon insertions at a greater distance from the joint. Consequently, they produce powerful movements and are not primarily involved in stabilization. They are the deltoid complex, the pectoralis major, the latissimus dorsi and the teres major. Rotator cuff disorder is one of the commonest afflictions of the shoulder and is a major cause of impairment of health in the young as well as in older individuals.1 Lesions of the rotator cuff should be recognized as different from those of other tendons in the body for a variety of reasons. The tendons of the rotator cuff blend intimately with each other and with the capsule. The insertion of the tendons, as a continuous cuff around the humeral head, permits the cuff muscles to provide an almost infinite variety of movements to rotate the head and to oppose unwanted movements generated by the larger effector muscles.2 In addition, the long head of the biceps may be considered a functional part of the rotator cuff because tension in the tendon helps to compress the humeral head into the glenoid (Fig. 15.2). Apart from their primary function (to rotate the humerus with respect to the scapula), the cuff muscles have two other actions: they compress the head of the humerus into the glenoid fossa and provide muscular balance (Box 15.1). The latter is mainly performed through eccentric contraction of the muscle. Both functions are extensively discussed in the online chapter Excessive range of movement: instability of the shoulder. Pathological changes associated with rotator cuff tendinopathy features are variable. Inflammatory tendinitis is a reversible process, associated with an inflammatory infiltrate, increased vascularity and hyperaemic changes within the rotator cuff tendon.3 Partial rotator cuff tears may develop within the substance of the tendon on either the acromial (bursal) or articular surface of the tendon.4 Most of the lesions occur near to the tendon insertion side. Full thickness tears are often initiated by a partial tear. They can be associated with a traumatic event or can progress with normal daily use of the arm. The primary cause of tendon degeneration is age.5 Changes in the rotator cuff include diminution of fibrocartilage at the cuff insertion, diminution of vascularity, fragmentation of the tendon and disruptions of the attachment to the bone.6,7 Changes in the coracoacromial arch have been described in association with cuff disease and it is quite clear from both cadaver and clinical data that individuals with full thickness rotator cuff tears have changes in the acromial shape, with spur formation on the undersurface of the acromion and/or hypertrophy of the acromioclavicular joint.8–11 Although these data indicate a strong association between the presence of cuff tears and alterations of acromial contour,12–14 it is still unclear whether the change in acromial shape is the cause or the result of the cuff defect or if both are consequences of ageing.15 Recent studies suggest that acromial deformity is usually developmental. Most acromial ‘hooks’ develop within the acromial ligament as traction spurs (analogous to the traction spur in the plantar ligament at its attachment to the calcaneus – see Fig. 15.11). The traction results from loading of the ligament by the cuff, which is increased when superior instability and cuff degeneration are present.16,17 Changes in the microvascular supply to the rotator cuff also have a possible role in the pathogenesis of rotator cuff lesions.18 A hypovascular region exists at the ‘critical zone’ of the supraspinatus (the deep surface of the anterior insertion).19,20 Microangiographic studies demonstrate that inadequate vascular supply to this critical zone is present in the adducted position of the arm.21 Furthermore, microvascular supply changes within the thickness of the tendon: the acromial part has much better vascularity than the articular part.22–24 It is likely that a combination of age, anatomical changes and vascular insufficiency is responsible for rotator cuff ‘failure’.25 Throughout life the cuff is subjected to various adverse factors such as traction, compression, contusion, subacromial abrasion, inflammation and age-related degeneration. A lesion may start where the loads are the greatest and the vascular supply the lowest, i.e. at the deep surface of the anterior insertion of the supraspinatus.26 Each fibre rupture then generates other adverse effects: it increases the load on the neighbouring fibres, it compromises the blood supply of the tendon fibres by distorting the microcirculation and it exposes increasing amounts of the tendon to joint fluid that contains lytic enzymes. The cuff is gradually weakened and at increased risk of further failure. With subsequent loading episodes the pattern repeats itself, rendering the cuff weaker and progressively more susceptible to additional failure (Fig. 15.3).27 The incidence of rotator cuff tears has been studied both in cadaveric studies and in living subjects and found to range from 5 to 80%. All the studies show a strong relationship with age: rotator cuff tears are rare before age 40 and common after age 60.28 However, almost all of the reported cadaver studies failed to correlate cuff disorder with a history of clinical symptoms (Table 15.1). Some of the most important studies in living subjects have concerned the prevalence of cuff lesions in asymptomatic patients (Table 15.2). They all demonstrated a high prevalence of tears of the rotator cuff in asymptomatic individuals, an increasing frequency with advancing age and compatibility with normal, painless functional activity. Table 15.2 Incidence of rotator cuff tears in asymptomatic patients Given the high prevalence rate of asymptomatic macroscopic rotator cuff lesions, it is unwise to rely solely on imaging techniques (sonography, computed tomography (CT), MRI) for a diagnosis.49 The examiner should be wary of the common belief that what is found on technical investigation is always relevant to the cause of the patient’s pain.50 Diagnosis should first of all be made functionally; paraclinical and technical investigations have a secondary function only. During resisted movements, pain and weakness, separately or in combination with each other, are sought. If pain only is found, this points to an uncomplicated tendinitis or to a partial thickness lesion. A combination of pain and weakness brings a partial (full thickness) tendinous rupture to mind. Painless weakness is usually the outcome of a massive tear of a rotator cuff tendon or of a neurological problem. It is worth emphasizing once again that, when performing resisted movements at the shoulder, it is very important to use the correct technique, as has been explained earlier (see p. 214). If this is neglected, misdiagnosis can easily result.51 Treatment options are also determined only by the outcome of the clinical examination and not by the extensiveness of the (anatomical) lesion. Asymptomatic cuff lesions, for instance, in which the shoulder does not bother the patient but imaging studies document a partial or even full thickness lesion in the cuff tendon, should not receive treatment. However, if the rotator cuff lesion is symptomatic, it will usually not heal by itself because rotator cuff tendinitis is not self-limiting.52 Initial treatment for a symptomatic cuff lesion should always be conservative, no matter what the result of imaging may be. Non-operative treatment consists of either deep friction transversely to the affected tendon fibres or local infiltration with small amounts of triamcinolone at the tenoperiosteal junction of the affected tendon. In recurrent cases it is wise to add functional exercises for strength and proprioception (see online chapter Excessive range of movement: instability of the shoulder).53 The effectiveness and safety of steroids for the treatment rotator cuff disease remains the subject of much controversy. Repeated injections with steroids are believed to produce tendon atrophy or to reduce the ability of damaged tendon to repair itself. Animal studies suggest that corticosteroids damage the ultrastructure of collagen molecules54 and reduce collagen density, as well as inhibiting the reparative properties of tendon by inhibiting tendon cell migration and synovial fibroblast proliferation.55 This has been shown experimentally to weaken collagen fibres and precipitate tendon ruptures.56–58 In human subjects, repeated injections have been correlated with softening of the rotator cuff substance59 and an inferior result of surgical repair.60 Other studies, however, failed to find a deleterious long-term effect of corticosteroid injections in animal tendons,61,62 and a recent case-controlled study suggests that corticosteroid use in patients with ‘subacromial impingement’ should not be considered a causative factor in rotator cuff tears.63 Although rotator cuff disorders are generally believed to benefit from steroid injections, evidence for the efficacy of the injections is difficult to demonstrate. Most reviews have found conflicting results,64 which can be explained mainly by the fact that very heterogenous populations with poorly designed subgroups were used.65 In other studies that used a better anatomical classification, local triamcinolone infiltrations were shown to be superior to placebo66–70 and to methylprednisolone71 in reducing pain, improving active abduction and reducing functional limitation. The success rate of the infiltrations is further increased if precise diagnostic and infiltration techniques are used.72 In a randomly allocated double-blind study, Hollingworth et al compared two different methods of corticosteroid injection. The method of anatomical injection after diagnosis by the technique of selective tissue tension gave a 60% success rate, compared with the method using tender or trigger point localization, which produced only 20% success.73 Also, a recent meta-analysis concluded that injections of corticosteroids are effective for improvement for rotator cuff tendinitis for up to a 9-month period.74 • The infiltration is always on the tenoperiosteal junction, never in the body of the tendon. • The arm should be rested for 2 weeks following the infiltration. • No more than three consecutive infiltrations should be given. Calcium deposits may form in the tendons of the rotator cuff. The aetiology is still a matter of speculation but it is generally accepted that degeneration precedes calcification. The incidence of calcification ranges from 3 to 20%75,76 and in most instances the lesion is completely asymptomatic.77 The highest incidence occurs in those aged between 31 and 50,78,79 and calcification is absent in elderly patients. The disease is usually self-limiting with a variable natural course: 80% of calcific lesions show spontaneous resorption over a period of 3 years.79 If the lesion causes symptoms, these are treated in the same way as uncomplicated tendinitis of the rotator cuff. The treatment of choice is infiltration with triamcinolone. If the pain reappears after initially successful treatment, the calcium deposits can be dissolved with weekly infiltrations of procaine 0.5%.80 Surgical intervention is seldom necessary but if it is indicated, most calcifications can easily be removed by arthroscopic procedures.81 In recent years extracorporeal shock wave therapy has been proposed as an alternative to operative treatment.82,83 • Resisted horizontal adduction (Fig. 15.4): the examiner stands at the painful side and stabilizes this shoulder with one hand. With the other hand, he grasps the patient’s arm just above the elbow and brings it into horizontal abduction. The patient is now asked to push the arm forwards against the examiner’s hand. This tests the anterior portion of the deltoid. • Resisted horizontal extension (Fig. 15.5): this is the exact opposite of the previous test. The patient is asked to push backwards, the examiner applying counterpressure in an anterior direction. The posterior fibres of the deltoid are tested in this movement. Most of the lesions occur at the tenoperiosteal insertion into the greater tuberosity. Inflammation and partial tears may develop within the substance of the tendon on the acromial surface (bursal side) or the deep surface (articular side of the tendon).84 If situated on the deep part, pain on full passive elevation is also present. This is believed to be caused by the abutment of the deep surface of cuff insertion against the glenoid rim at the extremes of motion (Fig. 15.6).85 If situated on the bursal part of the tendon, a painful arc is found. Cyriax regarded this as the most common cause of a painful arc on shoulder elevation.86 A third possibility is a lesion that involves both superficial and deep aspects tenoperiosteally. In this case, pain on full passive elevation is present, together with a painful arc (Fig. 15.7). Figure 15.8 summarizes the differential diagnosis of painful resisted abduction. The main problem in treatment is finding the structure involved. Although the tendon lies quite superficially, many have difficulty in localizing it. It cannot be easily localized with the arm in the neutral position at the side. Although the greater tuberosity points laterally in this position, part of the insertion can be covered by the outer rim of the acromion. Moreover, all structures here feel the same on palpation. Therefore, it is better to bring the upper arm into full medial rotation by asking the patient to put the lower arm behind the back, with the elbow bent to 90° (Fig. 15.9). In this position the tenoperiosteal insertion lies anterior to the acromion.87,88 The fibres at the insertion are now situated in a sagittal plane because the tendon curves around the base of the coracoid process as a result of the medial rotation. A tuberculin syringe, filled with 1 mL of triamcinolone, is fitted to a 2.5 cm needle. The patient sits in the same position as for palpation, the arm behind the back. After the insertion has been precisely located, the needle is thrust in vertically downwards at its centre (Fig. 15.10). The needle glides in smoothly initially, until it encounters the tenoperiosteal junction, at which point the typical tendinous resistance is felt. When the needle is thrust in a little further, it is arrested against the bone. Then 1 mL of triamcinolone is infiltrated at 5–10 different places over an area of 1 cm2, in close bony contact. During the whole infiltration, a typical counter-pressure is felt. Treatment that leads to good but temporary results is a common experience in supraspinatus tendinitis. After one or two infiltrations the pain has disappeared but recurs a few months later. The patient should then be sent for standard radiography of the shoulder. If some intratendinous calcification is confirmed, 4–5 weekly infiltrations with 5 mL of procaine 2% are administered. In most cases this is sufficient to dissolve the calcium deposits and to alleviate the pain. If no calcification is visible, the patient must be referred to the therapist for deep transverse friction because it is unwise to infiltrate the tendon repeatedly, even with small doses such as 10 mg of triamcinolone. In cases of recurrent tendinitis it is also good practice to look for an underlying cause. This may be a small multidirectional or superior instability or an anatomical divergence in the acromial roof that causes recurrent impingement. The diagnosis and treatment of the former have been discussed earlier (see online chapter Excessive range of movement: instability of the shoulder). The diagnosis of the latter is through a lateral X-ray that visualizes the so-called ‘supraspinatus outlet’ – the space between the coracoacromial roof and head of the humerus (Fig. 15.11). If there is an anatomical divergence in the supraspinatus outlet, and the tendinitis tends to recur despite proper treatment, surgical decompression (deletion of anterior and inferior parts of the roof) is highly recommended.89 The treatment of supraspinatus tendinitis is summarized in Figure 15.12. The patient adopts the same position as for infiltration: seated with the back against the couch, the arm behind the back. The therapist stands laterally on the patient’s painful side. The index finger of the ipsilateral hand, reinforced by the middle finger, is placed at the medial edge of the insertion. The hand is meanwhile stabilized by the thumb placed against the lateral aspect of the upper arm, almost vertically under the index finger (Fig. 15.13). When the index finger is pulled outwards over the tendon, pressure is applied. This is the active phase of the friction. The pressure is directed caudally, not towards the clavicle – easily obtained if the stabilizing thumb is placed rather low on the upper arm, the nail of the finger that applies friction thus pointing upwards. The patient sits on a chair with the arm abducted sideways to the horizontal, the elbow and forearm resting on a couch. In this position the musculotendinous junction lies in the supraspinous fossa at the angle between the scapular spine and the acromion, just posterior to the clavicle. The therapist stands at the pain-free side facing the shoulder. The ipsilateral middle finger reinforced by the index finger is placed deeply into the scapuloacromial angle, holding the slightly bent finger parallel to the muscle (Fig. 15.14). Friction is given by pronation–supination movements of the lower arm, the active moment being in supination. Friction is applied for about 15 minutes. Cure is expected after about 10 sessions. If resisted abduction is found to be both weak and painful, a partial rupture of the supraspinatus tendon is most likely.90 Ruptures of the rotator cuff occur most frequently at the supraspinatus tendon. A full-thickness defect usually starts at the critical zone (articular side of the anterior part near to the bicipital groove) and may propagate either in the direction of the infraspinatus or towards the subscapularis tendons.91,92 Conservative treatment is reasonable for most partial ruptures of the supraspinatus tendon.93 Treatment is relief of pain, achieved by infiltration of 1 mL of triamcinolone at the tenoperiosteal insertion and into the most distal part of the tendon. The same position and technique are used as for an uncomplicated tendinitis. The supraspinatus muscle initiates active elevation of the arm and is active during the entire arc of abduction. It is responsible for about 50% of the torque and can abduct the joint without action of the deltoid.94 Therefore a total rupture of the supraspinatus tendon presents as painless weakness on resisted abduction. Previously it was believed that the arm could not be abducted actively by the deltoid muscle alone if some contraction of the supraspinatus did not initiate the movement.95 However, studies in which the suprascapular nerve and the axillary nerve were blocked have shown that both the supraspinatus and the deltoid muscles are capable of initiating elevation of the arm, in both sagittal and coronal planes.96–98 This is not in accord with what is found clinically. When the supraspinatus tendon is massively ruptured, the patient is unable to initiate active scapulohumeral abduction. Starting from a position of 0° (the arm hanging by the side), the deltoid muscle only pulls the humerus upwards. Elevation is then only produced by rotation of the scapula in relation to the thorax and not by any movement between scapula and humerus. This is explained by the superior displacement of the humerus that occurs during active contraction of the deltoid in the absence of an intact supraspinatus tendon.99,100 In a normal situation the rotator cuff muscles form a supplementary musculotendinous glenoid which, in conjunction with the osseous glenoid, holds the humeral head stable. Experimental sections of the supraspinatus tendon also show the humeral head to move in a cranial direction until the superior humeral load is applied directly to the acromion (Fig. 15.15).101 This phenomenon has been referred to as ‘the spacer effect’102 and is one of the most significant plain radiographic signs of massive cuff deficiency.103 The lesion usually affects middle-aged and elderly people. In patients under 40 years of age a rupture is usually acute and results from indirect trauma, such as a fall on the outstretched hand.104,105 In most cases the rupture is due to a chronic failure of the tendon: repeated failure of small groups of fibres leads to progressive weakness of the supraspinatus, making it increasingly susceptible to damage from lesser loads.106,107 The observation that major cuff defects may occur without recognized injury has led to the concept of ‘creeping tendon failure’.108 Frequently, because the patient is unable to move the arm actively, an immobilizational arthritis will set in after a few months and a capsular pattern emerges (see p. 228). Because most total ruptures occur insidiously in the elderly, surgical correction to restore normal function will not be the first option.109 Some defects cannot be repaired simply because they only offer ‘rotten cloth to sew’ (McLaughlin).110 Many defects do not need to be repaired because they exist without causing much in the way of clinical symptoms.111 However, surgery should always be considered in a younger patient with a significant acute tear in a previously normal shoulder,112,113 and in the patient with a chronic tear associated with significant symptoms and not responding to conservative treatment. Fair functional results have been observed using open114,115 and arthroscopic techniques,116 but it is important to bear in mind the fact that repair does not restore the quality of the tendinous tissue. Reported recurrence rates after rotator cuff repair range between 15% and 90%.117,118 Because rotator cuff integrity is important to its function,119 long-term results of repair are better in younger patients with acute tears.120,121 For most supraspinatus ruptures the treatment of choice is conservative. The primary aim is to get rid of the pain. To that end, an infiltration with 10 mg of triamcinolone should be given at the remnants of the insertion into the humeral tuberosity to abolish the painful arc, following the same procedure as for uncomplicated supraspinatus tendinitis. The therapist should try to reach the inflamed tissue because infiltrating the gap is useless. Therefore the typical counterpressure on syringe and needle should be felt during the entire procedure. Once the painful arc has gone, patients should be encouraged to use the arm normally. To lift the arm up, they should initiate elevation via a swinging movement of the trunk so that the arm is thrown laterally until it reaches the point where the deltoid muscle becomes effective. It is also wise to prescribe functional exercises for the antagonists of the deltoid and the remaining rotator cuff muscles. In spite of the slight disability, the function of the joint is usually good and the patient should be capable of doing light work.122–124 Outcome studies report good to fair results in 60–90% of conservatively treated supraspinatus ruptures.125–127 Several neurological disorders may provoke painless weakness on resisted abduction. This may follow a subluxation of the humeral head. The axillary nerve innervates the deltoid muscle. Differential diagnosis is based on testing the strength of both the deltoid and infraspinatus muscles. Isolated painless weakness of abduction is found. A painful arc is not present, which differentiates this disorder from a supraspinatus rupture. Active elevation is difficult but possible (see online chapter Nerve lesions and entrapment neuropathies of the upper limb). This is most often the result of idiopathic neuritis, and seldom of an injury. The suprascapular nerve innervates both supra- and infraspinatus muscles. Weakness of abduction and lateral rotation is present. This disorder can be differentiated from a combined supra- and infraspinatus rupture by the absence of a painful arc (see online chapter Nerve lesions and entrapment neuropathies of the upper limb). It may happen that isometric movements indirectly provoke pain in structures other than the ones that are supposed to be tested. Cyriax called this phenomenon ‘transmitted stress’. During strong resisted adduction with the arm hanging alongside the body, the strong actions of the latissimus dorsi and pectoralis major pull indirectly on the acromioclavicular joint. Resisted adduction may therefore also provoke local shoulder pain in a chronic strain of the acromioclavicular joint. The pain will then be localized within the C4 dermatome and other passive tests will point to the acromioclavicular joint (see p. 241). Pain on resisted adduction of the arm may rarely be caused by a tendinitis of the long head of the biceps at the glenoid origin. Cyriax arrived at this conclusion after finding that resisted adduction proved to be painful with the elbow in extension but not if it was kept in flexion. As a consequence, the structure at fault must overlie both shoulder and elbow (see p. 269). The pain is mainly felt under the acromioclavicular joint. More often, however, a positive test will indicate a lesion of one of the adductors: pectoralis major, latissimus dorsi, teres major and teres minor.128

Disorders of the contractile structures

Introduction

Rotator cuff

Pathology

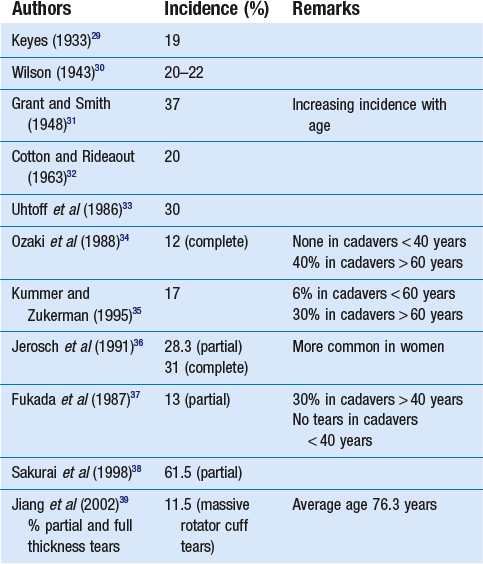

Incidence

Authors

Incidence (%)

Remarks

Petterson (1942)40

20 (partial and full)

50% in subjects 55–85 years of age

Milgrom et al (1995)41

50 (tears after age 50 years)

Rotator cuff lesions are a normal correlate of age; they often present without clinical symptoms

Sher et al (1995)42

15 (full), 20 (partial)

Significant increase of tears with age; defects are compatible with normal, painless, functional activity

Yamaguchi (2006)43

35.5% prevalence of a full thickness tear on the painless side

Sonography of 588 consecutive patients with unilateral shoulder pain

Tempelhof (1999)44

Rotator cuff tears in 23%

13% age 50–59 years

20% age 60–69 years

31% age 70–79 years

51% age > 80 years

Ultrasonographic study of 411 asymptomatic volunteers

Shibany (2004)45

Complete rupture of the supraspinatus tendon in 6%

Ultrasound examination of 212 asymptomatic shoulders at 56–83 years (mean: 67 years)

Kim (2009)46

0% age 40–49 years

10% age 50–59 years

20% age 60–69 years

40.7% > 70 years

Ultrasound and MRI investigation of asymptomatic individuals

Moosmayer (2009)47

Full thickness tears in 7.6%

15% age 70–79 years

420 asymptomatic volunteers aged 50–79 years

Yamamoto (2010)48

16.9% asymptomatic

20.7% total group

Prevalence of tears among the 683 residents of a mountain village in Japan

Diagnosis and treatment

Calcifying tendinitis

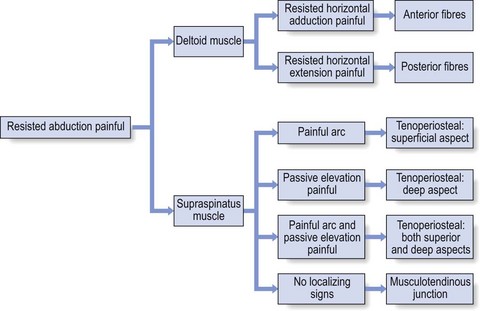

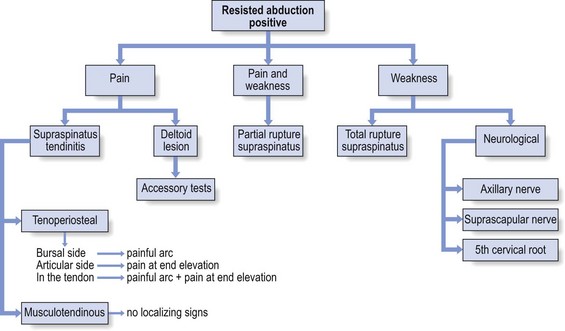

Resisted abduction

Pain

Deltoid muscle

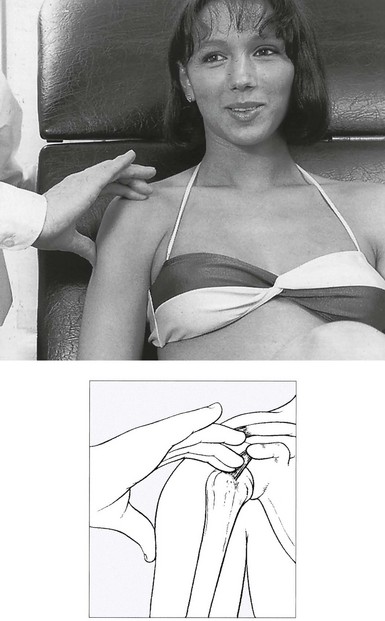

Supraspinatus

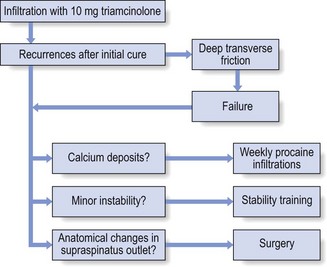

Treatment of tenoperiosteal lesions

![]()

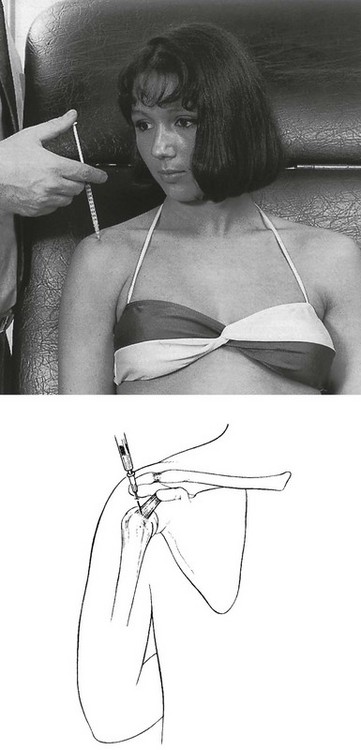

Localization by palpation

Technique: infiltration of the supraspinatus

![]()

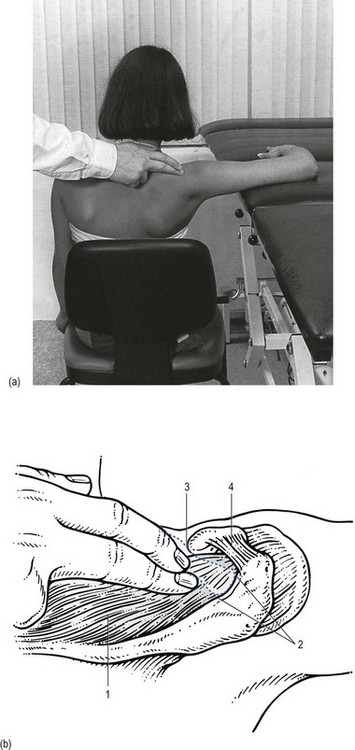

Technique: deep friction to the supraspinatus

![]()

Treatment of musculotendinous lesions

Technique: deep friction to musculotendinous lesions

Painful weakness

Treatment

Painless weakness

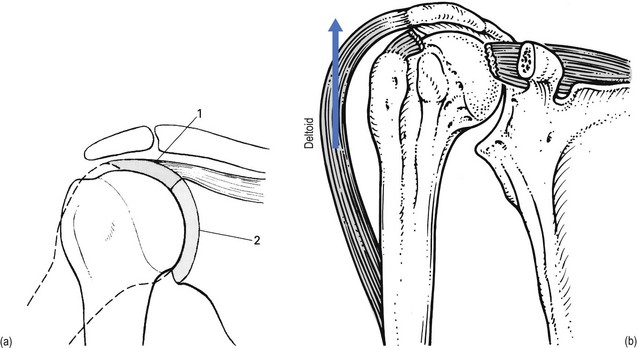

Total rupture of the supraspinatus tendon

Symptoms and signs

Treatment

Neurological lesions

Axillary nerve palsy

Suprascapular nerve palsy

Resisted adduction

Pain

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Disorders of the contractile structures