CHAPTER 20 Dislocations of the Child’s Elbow

INTRODUCTION

Dislocation of the elbow in children is the most common childhood dislocation, constituting about 6% to 8% of elbow injuries.72,118 In general, however, because the attachments of ligaments and muscles are stronger than the adjacent growth plate, forces exerted about most joints tend to result in epiphyseal injury rather than simple dislocation of the adjacent joint. The elbow is unique in children because type I and II fractures through the distal humeral epiphysis are uncommon; hence, the finding for dislocation.

The purpose of this chapter is to discuss the practical aspects of the cause, recognition, and the management of dislocations about the elbow joint in children. Because the elbow is the most common joint injured in childhood, the chapter on imaging (see Chapter 12) and chapters dealing with images of other conditions (see Chapters 14 to 18 and Chapter 21) should be carefully studied.

ANATOMIC FACTORS PREDISPOSING TO ELBOW DISLOCATION IN CHILDREN

Although the anatomy of the elbow joint was thoroughly discussed in Chapter 2, it is important to emphasize some of the anatomic differences that are unique to the pediatric elbow joint.

GROWTH PLATES, APOPHYSIS, AND SECONDARY CENTERS OF OSSIFICATION

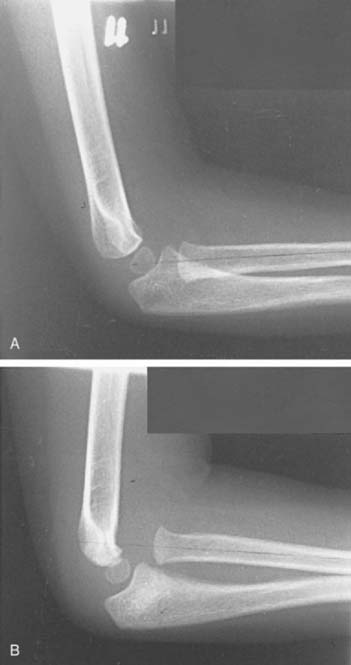

In general, the younger the child at the time of injury, the more difficult it is to assess the elbow, owing to the larger percentage of cartilage that is present about the elbow joint. Fortunately, new imaging modalities allow more accurate assessment.7,8 Yet, in the newborn or infant, it may be very difficult to diagnose an elbow injury or to determine whether it is a transcondylar fracture or a dislocation of the elbow (the former being much more common at this age). The ossific nuclei about the elbow joint are helpful in radiologic interpretation of elbow dislocation (see Chapter 12). The capitellum, whose center of ossification should be present by 6 months of age, facilitates the interpretation of radial head alignment, because a line drawn through the radial head should always intersect the capitellum no matter what view is taken (Fig. 20-1). This interpretation is improved even further with the appearance of the radial head secondary center of ossification, at around 5 years of age. The secondary center of ossification of the olecranon, which appears at about 9 years of age, allows a more accurate assessment of the position of the proximal ulna in relation to the distal humerus, an important consideration in the management of dislocations of the elbow in young children.

The lateral epicondylar apophysis is injured less frequently. In posteromedial dislocations, it may suffer avulsion, owing to a severe varus strain on the elbow and may need to be repaired or fixed surgically.5

ELBOW FLEXIBILITY

In children younger than 10 years of age, elbow stability is provided almost entirely by cartilage. Because of this, there is considerable flexibility in the elbow joint in children. It is not unusual for a child to be able to hyperextend the elbow joint by 10 or 15 degrees and to have a much greater degree of laxity than is seen in an adult or even an adolescent. It is this combination of hyperflexibility and a lack of osseous stability in a joint subjected to considerable trauma that predisposes the elbow joint to dislocation. The major stabilizing ligaments on the medial and lateral sides are attached to the distal humerus through apophyses—structurally weak areas that are prone to avulsion with subsequent loss of joint integrity. In the many syndromes and conditions such as Ehlers-Danlos and cutis laxa syndromes,111,119 ligamentous laxity is enhanced and stability is accentuated.

RADIAL HEAD AND NECK

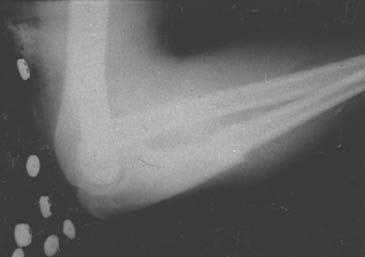

The radial head and neck in children are cartilaginous but have the same relative diameters as the radial head and neck in adults. Dislocation of the radial head, either as an isolated event or in association with a Monteggia fracture, or with dislocation of the elbow joint itself, is facilitated by the resiliency of the cartilaginous component. Children’s bones have plasticity and can be bent like the proverbial greenstick without fracturing. In the type A Monteggia lesion, for instance, it is conceivable that the ulna bends to the point of fracture, whereas the radius only bends to the point at which the radial head slips under the annular ligament and dislocates anteriorly (Fig. 20-2).

TYPES OF DISLOCATION OF THE RADIAL HEAD

CONGENITAL DISLOCATION

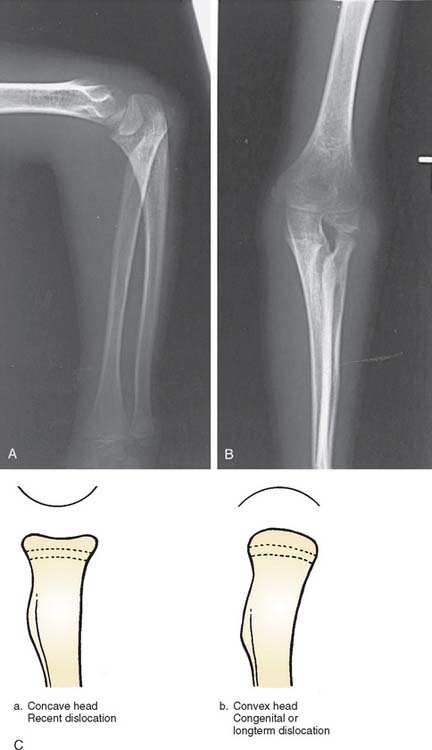

Congenital dislocation of the radial head is a controversial lesion, because some maintain this lesion does not exist at all and all such appearances are simply traumatic or developmental dislocations. This subject is discussed in more detail in Chapter 13. Here, I reserve the diagnosis of congenital dislocation for that entity in which congenital malformation of the extremity is obvious (Fig. 20-3). When isolated dislocation of the radial head is not accompanied by other congenital lesions, the congenital basis for the lesion cannot be substantiated. The long-standing nature of the dislocation can be inferred from the marked convexity of the radial head associated with elongation of the radial neck (Fig. 20-4).27,28 Congenital dislocation of the radial head may be associated with radioulnar synostosis, the synostosis almost always occurring between the proximal radius and the ulna.32–36

Hypoplasia of the capitellum associated with dislocation of the radial head strongly suggests that the dislocation is congenital. The radiologic appearance of congenital dislocations of the radial head has been emphasized by Miura.37 In congenital dislocations, the posterior border of the ulna is usually concave rather than slightly convex, with the radial head being dome-shaped with no central depression (see Fig. 20-3). Posterior congenital dislocation, which constitutes about 40% of congenital dislocations of the radial head, is associated with an accentuation of the normal convexity of the posterior border of the ulna. In fact, because we have not been able to diagnose this pathology, at best, we consider this a developmental problem.28

DEVELOPMENTAL DISLOCATION

Many instances of developmental or secondary dislocation of the radial head are misinterpreted as being congenital in origin.28 Developmental dislocation is defined as any dislocation of the radial head that results from maldevelopment of the forearm. There are many inherited and acquired disease processes affecting the growth plate of the forearm bones that result in asymmetric growth between the radius and the ulna and subsequent dislocation of the radial head. These include the nail patella syndrome, Silver syndrome, arthrogryposis, Cornelia de Lange syndrome, and cleidocranial dysostosis. Asymmetric growth also occurs in multiple exostoses or diaphyseal aclasis. The ulna is most frequently affected at the distal ulnar growth plate; the radius then overgrows relative to the ulna (Fig. 20-5). Paralysis of the muscles innervated by the C5-6 nerve root, as in a nerve root palsy, also predisposes to a gradual dislocation of the radial head that occurs over a number of years of growth or occasionally in infancy.17 Cerebral palsy also may produce isolated dislocation of the radial head through marked spasticity of the muscles attached to the radius (Fig. 20-6).21 Trauma to the radius or the ulna, resulting in asymmetric growth, may also produce dislocation of the radial head. Fracture of the neck of the radius that has not been corrected adequately may result in the proximal radial epiphysis growing laterally instead of toward the capitellum (Fig. 20-7).20–26

FIGURE 20-5 A to D, Dislocation of the radial head posterolaterally in a patient with multiple exostoses.

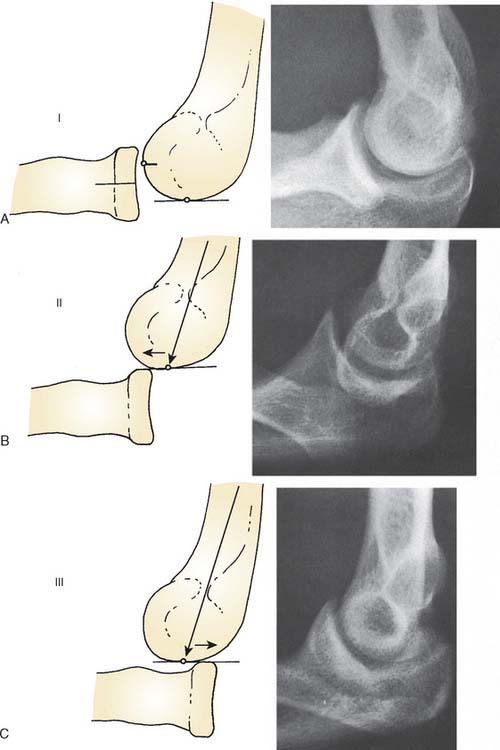

A detailed developmental posterior study at the Mayo Clinic describes several grades, or types, of radial head dislocation with characteristic radiographic appearance (Fig. 20-8). Types II and III are complete dislocations and are more obvious cosmetically but have relatively little functional loss except forearm rotation.28 Type I dislocations commonly are associated with late degenerative arthrosis and consist more of a subluxation than a frank dislocation. However, consistent with the definition of forearm maldevelopment, all types have a previous proximal ulnar bow.

There are few indications for operative treatment of developmental dislocation of the radial head. For example, a malunion of the radius and the ulna that is obviously directing the head of the radius laterally, posteriorly, or anteriorly should be corrected with an osteotomy to redirect the proximal radius or the deformed ulna19; otherwise, excision of the radial head can be effective to improve motion, lessen pain, or to improve cosmesis.

In patients with cerebral palsy, if the bicipital tendon appears to be subluxating the radial head anteriorly, lengthening the biceps may prevent future dislocation. Once the dislocation is well established, attempts to relocate the radial head probably should not be made, and the dislocation should be accepted. Future resection of the radial head at skeletal maturity can be performed if the head is cosmetically or functionally a problem. The gradual nature of the dislocation and adjacent changes in the surrounding tissues and bone make this type of relocation of the radial head much more difficult than the acute traumatic injury.26

RADIOGRAPHIC APPEARANCE

The radiographic appearance of a long-standing dislocated radial head is characterized by a rounded contour or convexity in contrast to the normal concave appearance (see Fig. 20-4). The posterior border of the ulna also may be concave rather than slightly convex in anterior dislocations of the radial head. Posterior dislocations result in a longer neck with a typical dome-shaped head. Even an isolated traumatic dislocation of the radial head, when it occurs in a very young child, may take on the appearance of a congenital or developmental dislocation with the passage of time. A relative increase in ulnar length in relation to the radius and the wrist is often noted. With posterior dislocation, proximal ulnar bowing also is prominent, and proximal radial migration of the radius may be present.28 The capitellum may be hypoplastic or, occasionally, even absent.38

Other factors characteristic of congenital or developmental radial head dislocations have been reported to be bilaterality of involvement,28 association with other congenital anomalies, familial occurrence, absence of traumatic history, and the presence of the entity in a patient younger than 6 months of age17–24 (see Chapter 13).

NATURAL HISTORY

Developmental dislocation of the radial head seldom causes severe pain with anterior dislocation. Patients may complain of clicking or impingement at the ulnohumeral joint with flexion of the elbow. In our experience, this is not seen until adolescence or adulthood. Posterior dislocation of the radial head typically creates a cosmetic protuberance that also may be a source of pain with excessive elbow motion.28 Aching in the region of the dislocation is common in the older child. A prominent ulna at the wrist and the resultant radioulnar subluxation at the distal end may result in some limitation of motion at the wrist, but discomfort is uncommon. There does not appear to be any progressive loss of motion with further growth, and the joint limitation, if present, remains static.20,28

TRAUMATIC DISLOCATION

The history is of limited value in these cases because these children are often young, prone to frequent elbow injuries, and unable to make a reliable contribution to the history. The radiograph, however, is usually diagnostic because it shows the rounded concave appearance of the radial head in the congenital or developmental dislocation (see Fig. 20-4).1–16

CLINICAL FEATURES OF ISOLATED ANTERIOR DISLOCATION

Radiographically, a line drawn through the shaft of the radius and the radial head will not intersect the capitellum when the radial head is dislocated (see Fig. 20-1). Children who have been subjected to child abuse may present with this particular injury, and again, the history will be difficult to elicit.

TREATMENT OF ACUTE ANTERIOR DISLOCATION

OPEN REDUCTION

Triceps Fascial Reconstruction

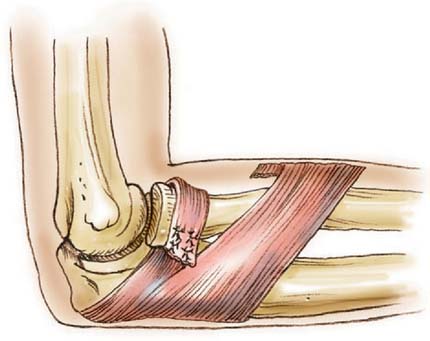

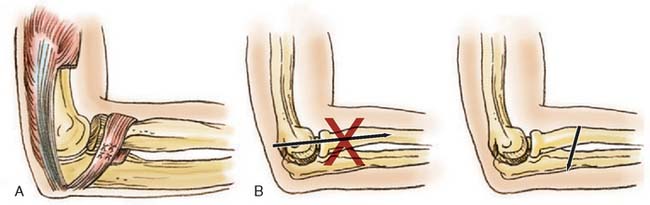

The technique of open reduction of an anterior dislocation of the radial head in children described by Lloyd-Roberts and Bucknill20 is one I have used with success. This consists of using the lateral portion of the tendon of the triceps for reconstruction of the annular ligament (Fig. 20-9A).

A posterolateral incision is preferred rather than a posterior incision, which may disorient the surgeon to the position of the radial head. The triceps tendon is identified, and a long (10-cm) strip is removed from the lateral margin, ensuring attachment at the distal ulnar insertion. The tendon is increased in length by continuing the dissection through the periosteum to a point opposite the neck of the radius, where it is then passed around the neck and sutured to itself and the ulnar periosteum with enough tension to hold the radial head in place. A Kirschner wire is then passed through the ulna into the radius to ensure solid fixation until the tendon has healed (see Fig. 20-9B).18

Specific care must be exercised when exposing the neck of the radius in a child. Unlike the adult, the radial nerve may be only a fingerbreadth below the head of the radius rather than the classic two fingerbreadths that is often referenced.

Fascial Reconstruction of the Annular Ligament

If inadequate, the annular ligament may be reconstructed. A strip of fascia is dissected from the forearm muscles but is left attached to the proximal ulna. The length of this fascial strip should be about 5 inches by 1/2 inch. It is passed around the neck of the radius, proximal to the tuberosity and distal to the radial notch of the ulna, and is brought around and fastened to itself with nonabsorbable sutures (see Fig. 20-9). Care should be taken to ensure that the length of this fascial strip is adequate. Cross-radioulnar pin fixation for 4 weeks is reassuring.

COMPLICATIONS

Relocation of an acute dislocation of the radial head in a child is usually successful, and recurrence is uncommon. If not reduced, limited motion and cosmetic deformity ensue. The dislocated radial head may also result in a relative shortening of the radius compared with the ulna, with subsequent subluxation at the radioulnar joint at the wrist. As a general rule, the radial head should not be excised in a child because this may further aggravate shortening of the radius by eliminating the proximal radial growth plate, which contributes about 30% of the final radial length. If there is pain or a grotesque appearance when the child is near skeletal maturity, the radial head is easily removed. In neglected patients, excision of the radial head may allow improved flexion and rotation and may alleviate complaints of pain and discomfort.28

PEDIATRIC MONTEGGIA FRACTURE DISLOCATION

The Monteggia injury is uncommon in children but by no means rare. In the 5-year period from 1978 to 1982 at the Winnipeg Children’s Hospital, 33 children were treated for a variety of Monteggia lesions. The true incidence of this fracture-dislocation is unknown, but it is more common than is generally appreciated. Olney and Menelaus53 reported 102 children with acute Monteggia lesions over a 25-year period.

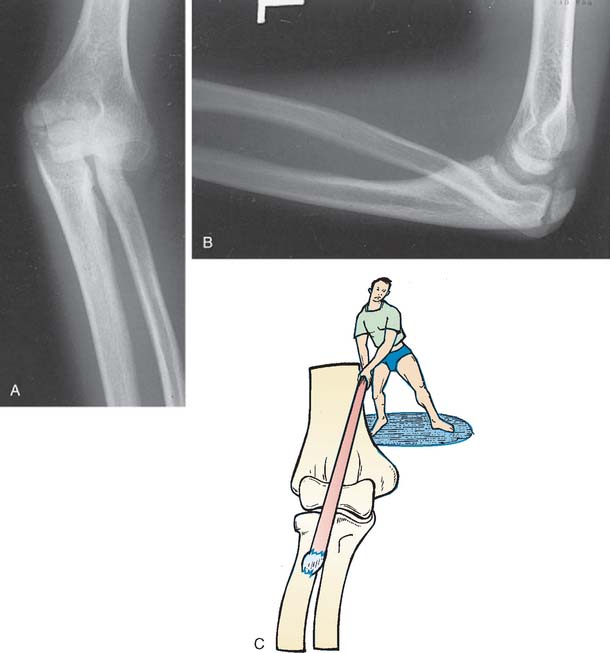

ETIOLOGY

The most common cause of dislocation of the radial head associated with an ulnar fracture in childhood is a hyperextension injury,44,62 followed by a hyperpronation injury.45 In hyperpronation, Bado39 pointed out that the bicipital tuberosity is posterior, thus predisposing the proximal radius to the greatest force during violent contraction of the bicipital tendon. In young children, the force generated by the biceps is less than that in the adult, and this mechanism probably is significant only in older children.

Because of the plasticity of the forearm bones, the radial head and neck may slip under the annular ligament and dislocate as the shaft of the radius bends. Indeed, many of the isolated traumatic dislocations of the radial head are undoubtedly variations of the Monteggia46–48 (Monteggia equivalent), in which the ulna has simply bent but not fractured. The radial shaft is bent to the extent that the head and neck are slipped from within the annular ligament, resulting in an apparent isolated dislocation of the radial head.30,43

CLASSIFICATIONS

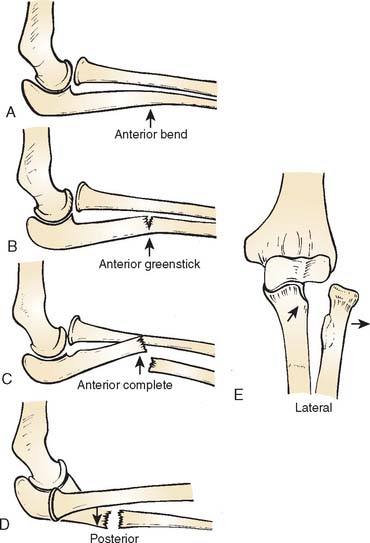

Classifications of the Monteggia lesion are based largely on the injury in adults39 (see Chapter 27). Because of differences in the configuration of the injury in childhood, the following pediatric classification is suggested to include dislocation of the radial head associated with the plasticity of the forearm bones in childhood (Fig. 20-10).

CLASSIFICATION OF PEDIATRIC MONTEGGIA LESIONS

Type A: Anterior dislocation of the radial head with anterior bowing of the ulna (Fig. 20-11).

FIGURE 20-11 A and B, Ulnar bend with lateral dislocation of the radial head, a type A Monteggia fracture dislocation.

Type B: Anterior dislocation of the radial head with greenstick fracture of the ulna (Fig. 20-12).

Type C: Anterior dislocation of the radial head with transverse fracture of the ulna (Fig. 20-13).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree