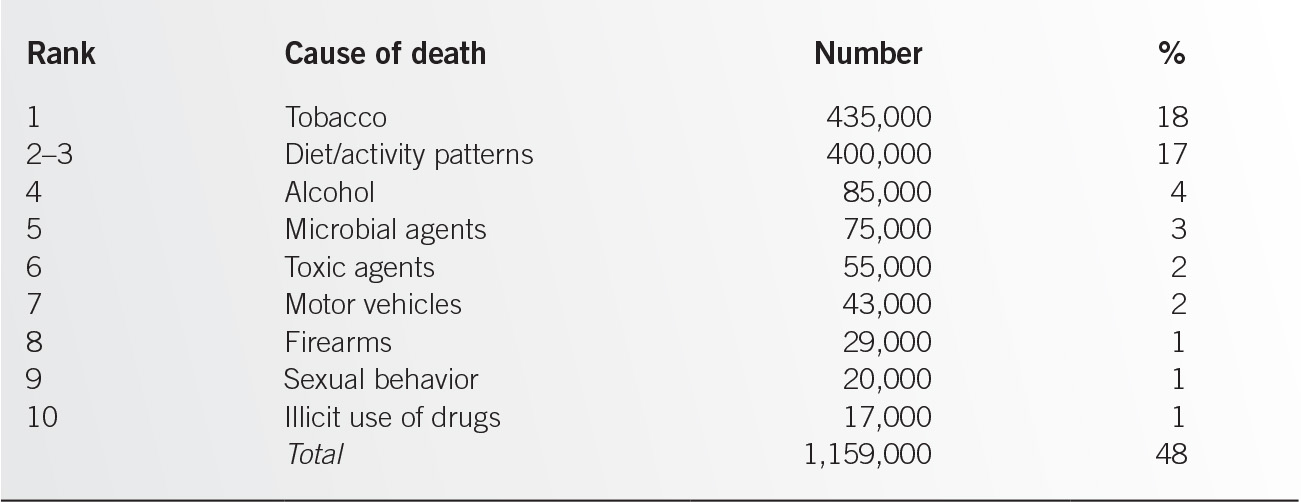

The leading causes of death and disability among adults are largely related to personal health and lifestyle behaviors or the actual causes of death (see Table 1.1-2), and may therefore be preventable through routine health maintenance interventions in the form of counseling, screening, immunizations, and preventive medications.3 These interventions are best delivered longitudinally as an integral component of the provider–patient contact—whatever the chief complaint—rather than as periodic, annual, or comprehensive physical examinations. As many provider–patient encounters occur only during times of illness or injury, the family physician must be prepared to be “opportunistic” and address health maintenance as a clinical issue whenever “teachable moments” arise, keeping in mind that, ultimately, patients must feel empowered to be responsible for their own health status. A few general guidelines will assist this process:

• Form a therapeutic alliance with the patient. All meaningful change will come from the patient. It is the role of the physician to provide the necessary tools for all patients to be as healthy as possible. It is not the physician’s role to make the patient change.

• Listen fully, look carefully, test sparingly. The history will provide the overwhelming majority of the necessary information. The physical examination will add small but important additional pieces of information. Screening tests have an important but limited role in adult care and should be ordered with careful consideration of their role in patient management.

• Counsel patiently. Behavior change is incremental and slow. Do not assume that the absence of change means the patient did not hear what you said. Repetition, understanding, encouragement, and patience will provide the best results. The family physician’s adult patients are assumed to be motivated to protect and improve their health status and capable of being responsible for the maintenance of their health. Adults are motivated by economic issues related to work and family care responsibilities as well as the need for independence and security for their future as retirees.

RISK ASSESSMENT: HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAM

The history will help direct the physical examination, screening tests, immunizations, preventive medications, and patient counseling/education. A systematic approach to patients will allow for a structured, thorough, and focused visit that meets the current and future needs of your patients. Each of these visits will begin with the history. This history may be relatively comprehensive if the patient is new or may represent a review and/or update of important interval developments. The past history, social history, and family history are particularly important in the risk assessment.

Besides identifying chronic diseases and medications, including preventive meds, the past history can include a health maintenance section that lists previous screening tests and immunizations. The social history includes important health behaviors, such as physical activity, dietary habits, substance use, etc., but it may also contribute to a broader understanding of the patient (e.g., hobbies, education, family status) and yield information with potentially important implications for the health of the patient (e.g., high-risk occupations, incarceration, travel to endemic disease areas, exercise and diet patterns).

A review of medical conditions that occur in the patient’s family allows the physician to develop a broader understanding of health concerns that may arise in the future for the patient. A general family history should encompass three generations: up one generation (parents), down one generation (children, if any), and the index generation (siblings, if any). Basic information in the family history includes age, whether the person is alive or dead, and important medical conditions for each person. For persons who are dead, the age and cause of death should be noted as well as any additional medical conditions that may have been present.

Screening Tests

Screening to detect the presence of asymptomatic disease is an important component of health maintenance and can often be accomplished at any patient visit. Frame4 developed criteria to consider when selecting a disease and test to use for screening:

• The condition must have a significant effect on the quality and quantity of life.

• Acceptable methods of treatment must be available.

• The condition must have an asymptomatic period during which detection and treatment significantly reduce morbidity and mortality.

• Treatment in the asymptomatic phase must yield a therapeutic result superior to that obtained by delaying treatment until symptoms appear.

• Tests that are acceptable to patients must be available at a reasonable cost to detect the condition in the asymptomatic period.

• The incidence of the condition must be sufficient to justify the cost of screening.

• Test sensitivity, specificity, and positive predictive value are important factors in the selection and evaluation of screening tests. Poor sensitivity or specificity can lead to a high rate of false-positive and false-negative results, both of which carry potentially serious consequences for patients.

Follow-Up of Screened Patients is an Important Adult Health Maintenance Strategy

The single most important factor predicting whether cancer screening is obtained in the office setting may be the incorporation of a routine health maintenance visit in the practice regimen.5 Screening results must be evaluated and incorporated into the patient record as this information is necessary to identify individuals for needed follow-up testing. Accuracy in testing and reporting of results is an important consideration. Laboratories used to analyze screening tests must adhere to national standards. Potential screening costs and morbidity may become issues for patients in the event of follow-up testing and treatment.

Immunizations6

Vaccination against infectious diseases is an important and cost-effective component of health maintenance. Many children and adults have not received the vaccines and toxoids that are indicated to protect them against potentially life-threatening diseases. Office procedures to improve compliance with immunization schedules are recommended and consistent with general office-based strategies to incorporate preventive services.

• Have office staff routinely assess patient’s immunization status, making sure that appropriately complete checklists are being used.

• Generate reminders automatically.

• Send reminder postcards.

• Establish standing orders in outpatient and inpatient settings that allow nurses to administer routine immunizations (e.g., annual influenza vaccine).

• Provide patients with materials on vaccine-preventable diseases.

• Provide medical record audit feedback to clinicians on their patients’ panel immunization rates.

Preventive Medications

This important component of adult health maintenance, often underutilized, involves the use of medications or supplements prospectively to prevent potential future diseases. Indications (benefits), risks of use and nonuse, dosage, precautions, and possible side effects of preventive medications are basic issues for the family physician in helping patients decide whether or not to adopt a specific intervention as a health maintenance strategy.

Counseling and Patient Education

Adult health maintenance programs should promote lifestyle change by explaining the links between risk factors and health status. Risk factor assessment and counseling with adult patients should help them acquire information, motivation, and skills to adopt and maintain healthy behaviors. Recommended counseling strategies include the following:

• Develop/utilize a therapeutic alliance.

• Counsel all patients.

• Ensure that patients understand the relationship between behavior and health.

• Jointly assess barriers to change.

• Gain patient commitment to change.

• Involve patients in selecting risk factors to change.

• Be creative, flexible, and practical, and use a combination of strategies.

• Design a behavior modification plan.

• Monitor progress through follow-up contact.

• Involve office staff (team approach).

EFFECTIVE PHYSICIAN AND OFFICE-BASED STRATEGIES

The following strategies have been shown to enhance the quality and quantity of health maintenance interventions.7

• Involve the office staff. A team approach to the delivery of preventive services is highly effective. Nursing and other members of office or clinic staff are often able to communicate with patients very effectively. Examples of specific staff functions include reviewing records to prompt clinicians and patients regarding preventive care, updating patient care flow sheets or computerized records, issuing reminders to patients and clinicians, following up on test results, and helping patients gain access to community resources. All immunizations and many screening activities can be successfully provided by nurses or allied health professionals. The team approach resolves the major barrier physicians face in implementing preventive care and recommendations: lack of time.8

• Incorporate routine documentation tools into your practice. Use chart-based or electronic medical record (EMR) systems, and include reminder postcards/emails for patients to alert them to the need for specific prevention interventions. Also use patient flow sheets for preventive care (e.g., smoker, due for Td or mammogram), wall charts and posters that inform patients that health maintenance is a practice priority, and prevention prescription pads to allow the clinician to write brief risk-reduction behavioral prescriptions for patients.

• Facilitate patient adherence. Make available patient education materials and information regarding community resources to help patients. Patient-held mini-records or direct patient access to their EMR promote increased responsibility among patients for their own health maintenance activities.9 Patient education materials should also be appropriately directed in terms of the patient’s literacy level and other pertinent factors (e.g., older than 60 years, requiring large print, etc.).

• Establish health maintenance guidelines (standards and objectives) for the practice, and evaluate achievement through audits and continuous quality improvement approaches. Practice systems to foster adult health maintenance activities can be most effectively evaluated through periodic reviews of charts or EMRs and specifying other indicators of quality. To obtain or maintain National Commission on Quality Assurance (NCQA) accreditation, health care organizations are now required to conduct such audits, which usually include such indicators as immunization history and various cancer screening tests.

• Develop minicounseling topics. Ten preventive topics, 3 to 10 minutes in duration and updated as necessary, can maximize the impact of “teachable moments.” The list may include exercise, smoking cessation, stress reduction, injury prevention, discipline and parenting skills, and family health promotion.

• Reminder or prompting systems. Generate adherence reminders, either manually or by computer, as a systemized approach to tracking patients in need of routine preventive care.10

REFERENCES

1. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/recommendations.htm. Accessed June 5, 2014.

2. Hoyert DL, Xu J. Deaths: leading causes for 2012. Natl Vital Stat Rep 62(6):9–10.

3. Mokdad AH, Marks JS, Stroup DF, et al. Actual causes of death in the United States, 2000. JAMA 2004;291(10):1238–1245.

4. Frame PS. Health maintenance in clinical practice: strategies and barriers. Am Fam Physician 1992;45(3):1192–1200.

5. Ruffin MT, Gorenflo DQ, Woodman B. Predictors of screening for breast, cervical, colorectal, and prostatic cancer among community-based primary care practices. J Am Board Fam Pract 2000;13:1–10.

6. Immunization Schedules. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/schedules/index.html. Accessed June 2, 2014.

7. Yano EM, Fink A, Hirsch SH, et al. Helping practices reach primary care goals. Lessons from the literature. Arch Intern Med 1995;155(11):1146–1156.

8. Strange KC, Fedirko T, Zyzanski SJ, et al. How do family physicians prioritize delivery of multiple preventive services? J Fam Pract 1994;38(3):231–237.

9. Krist AH, Woolf SH, Rothemich SF, et al. Interactive preventive health record to enhance delivery of recommended care: a randomized trial. Ann Fam Med 2012;10(4):312–319.

10. Frame PS. Computerized health maintenance tracking systems: a clinician’s guide to necessary and optional features. A report from the American Cancer Society Advisory Group on Preventive Health Care Reminder Systems. J Am Board Fam Pract 1995;8(3):221–229.

| Health Maintenance for Infants and Children |

Health maintenance visits provide the physician with an excellent opportunity to practice preventive medicine and establish an ongoing relationship with the child and his or her family. At each visit, the child should be evaluated for early disease processes, development, and behavioral problems. In addition, the appropriate screening tests, immunizations, anticipatory guidance, and counseling must be provided. A good resource is the book Bright Futures: Guidelines for Health Supervision of Infants, Children, and Adolescents from the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) and other resources available online at their web site. This chapter covers children from birth to 10 years.1

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

History

The initial history should address birth history, family history, social history, living environment, allergies, medications, and a complete medical history (including injuries, dietary history, growth, development, and behavioral problems). With each visit the history should be reviewed and updated for any changes.

Physical Examination

The physical examination should be complete with particular attention to those aspects appropriate for the child’s age.

Developmental Assessment

The child’s developmental level should be assessed at each visit. The Denver Developmental Screening Test is a widely used assessment tool. Table 1.2-1 includes a listing of some developmental highlights that can be used for a rapid and informal developmental screening. Some questionnaires, such as “Ages and Stages Questionnaires,” can be purchased and may be used to help evaluate communication, gross motor, fine motor, problem-solving, and personal–social skills of children at different ages.2

SCREENING

Table 1.2-2 presents a summary of the screening recommendations outlined below. A listing and schedule of all AAP Recommendations for Preventive Pediatric Health Care is available at the Bright Futures link: http://www.aap.org/en-us/professional-resources/practice-support/Periodicity/Periodicity%20Schedule_FINAL.pdf.

Developmental Milestonesa |

Age | Developmental milestones |

2 wk | Lifts head prone |

| Follows to midline |

| Responds to noise |

2 mo | Smiles responsively |

| Follows past midline |

| Lifts head 45 degrees |

4 mo | Grasps rattle |

| Rolls over one way |

| Laughs |

| Squeals |

6 mo | Sits briefly without support |

| Reaches for objects |

| Smiles spontaneously |

9 mo | Transfers object from one hand to another |

| Stands holding on |

| Plays peek-a-boo |

| Feeds self a cracker |

1 yr | Stands momentarily |

| Walks holding on to furniture |

| Says mama, dada (now specific) |

| Thumb–finger grasp |

15 mo | Stands alone |

| Walks alone |

| Drinks from a cup |

| Says three words other than mama, dada |

18 mo | Mimics household chores (sweeping) |

| Makes tower of two or three cubes |

| Indicates wants |

2 yr | Points to body parts |

| Scribbles |

| Handles a spoon well |

| Says two-word sentences |

| Kicks a ball |

aThese milestones should have been attained by 75% to 90% of children by the age indicated.

Childhood Screening Recommendations |

Condition | Recommendation |

Congenital diseases | Newborn screening |

Growth | Length, weight, and head circumference first 2 yr; BMI percentile starting at age 2 yr |

Hypertension | Blood pressure starting at age 3 yr |

Hearing | Newborn hearing screen; subjective assessment at all visits |

Vision | Red reflex and corneal light reflex during first week of life and at 6 mo; cover–uncover test during first year; and visual acuity starting at 3 yr |

Anemia | Age 9–12 mo with hemoglobin/hematocrit |

Autism | Surveillance at each visit; ASD screen at age 18 and 24 mo |

Tuberculosis | Screening questions; TB skin test if high-risk |

Lead | Screening questions 6 mo–6 yr; blood lead test if high-risk |

Lipid disorders | Screen all children aged 9–11 yr (and 18–21 yr) and high-risk children over 3 yr with lipid profile |

• Newborn screening. Every state has its own regulations, and, as such, clinicians should be familiar with their own state’s guidelines. Most states screen for at least phenylketonuria (PKU), congenital hypothyroidism, galactosemia, and sickle cell disease. Infants screened for PKU earlier than 24 hours after birth should be screened again before the second week of life. Other commonly screened diseases include congenital adrenal hyperplasia, maple syrup urine disease, homocysteinurea, biotinidase deficiency, and cystic fibrosis.3 Primary care physicians must be aware that the expanded newborn screen can have up to 3% false-positive results, which can lead to increased parental stress, additional testing, and cost.4

• Growth. Measuring growth and following its progression over time can help identify significant childhood conditions. Length, weight, and head circumference should be measured at birth, at 2 to 4 weeks, and at 2, 4, 6, 9, 12, 15, 18, and 24 months of age. BMI percentiles should be plotted and calculated annually for all patients aged 2 years and older.5,6 BMI percentiles between 85 and 95 are classified as overweight, while obesity is in the 95th percentile or greater. Some disease-specific growth charts are available, for example, premature infants and Down syndrome. The United States Preventive Services Task Force7 (USPSTF) recommends that clinicians screen children aged 6 years and older for obesity and offer or refer them to comprehensive, intensive behavioral interventions to promote improvement in weight status.

• Blood pressure. Blood pressure should be measured beginning at 3 years of age during routine office visits. Hypertension in children is defined as persistent blood pressure elevation at or above the 95th percentile based on gender, age, and height tables, while prehypertension is between the 90th and 95th percentiles.8

• Hearing. All states require universal newborn hearing screening, with both the USPSTF and the AAP supporting that recommendation. The AAP also recommends follow-up periodic hearing screening, including audiometry and subjective assessments of hearing, including checking for a response to noise produced outside an infant’s field of vision, noting an absence of babbling at 6 months of age, assessing speech development, and inquiring about parental concerns. These should be performed repeatedly, especially during the first year of life.1,7

• Vision. All children should be screened for a red reflex (looking for malignancy of the retina) and a symmetrical corneal light reflex (looking for esotropia) during the first week of life and again at 6 months of age. In the first year of life, children should also be screened with the cover–uncover test. At age 3 years, a photo screen is recommended by some groups. The AAP recommends picture tests, such as LH test or Allen cards, at age 3 to 4 years old. AAP also states that children over 4 years old can be screened with Snellen letters, Snellen numbers, and Tumbling E charts.9

• Anemia. All children should be screened for anemia using either hemoglobin or hematocrit testing at approximately 9 to 12 months of age. Preterm infants and low-birth-weight infants who are fed with low-iron formulas should be screened by 6 months of age. Children with the following risk factors should have a repeat screening for anemia 6 months after their initial screen: preterm or low-birth-weight infants, breastfed infants who do not receive iron-supplemented foods after 6 months of age, children who consume more than 24 ounces of cow’s milk a day after age 12 months, and infants in low-income families.1

• Autism. AAP recommends surveillance for autism spectrum disorder (ASD) at each visit and routine autism screening at 18 and 24 months. Surveillance factors include a sibling with autism; parental concern, inconsistent hearing, unusual responsiveness; other caregiver concern; and clinician concern. Various ASD screening tools are available.1

• Tuberculosis. Annual tuberculosis (TB) testing is recommended for children in high-risk populations. High-risk questionnaire with a yes to any of these questions necessitates screening with a tuberculin skin test.10

• Does your child have regular contact with adults who are at high risk for tuberculosis (such as homeless or incarcerated persons, persons with HIV, persons who use illicit drugs)?

• Has your child had contact with someone infected with tuberculosis?

• Is your child infected with HIV or other immunosuppressive disorders?

• Was any household member, including your child, born in an area where TB is common (i.e., Africa, Asia, Latin America, Caribbean)? Or has anyone in your family traveled to one of these areas?

• Lead. All children aged 6 months to 6 years should be assessed for risk of lead exposure using a structured questionnaire (see questions below).1 Any child for whom an answer to any of the questions is yes should be considered high risk and have whole-blood lead level testing. Those with blood levels less than 10 µg per dL should be retested once a year until age 6. Some groups advocate screening all children at 12 months of age. Recommended questions for assessing lead exposure risk (one yes or I don’t know is considered positive):

• Does your child live in or regularly visit a house that was built before 1950 and has peeling or chipping paint?

• Does your child live in or regularly visit a house built before 1978 with recent, ongoing, or planned renovation or remodeling?

• Does your child have a brother or sister, housemate, or playmate being followed or treated for lead poisoning (blood lead levels greater than 15 µg per dL)?

• Does your child live with an adult whose job or hobby involves exposure to lead? (Examples include stained glass work, furniture refinishing, and ceramics.)

• Does your child live near an active lead smelter, battery recycling plant, or other industry likely to release lead?

• Lipid disorders. In 2011, an expert panel sponsored by the United States National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) revised the guidelines that were initially developed by the AAP and the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP). In these guidelines, universal screening is recommended for children aged 9 to 11 years (and again for adolescents between ages 18 and 21 years), while children at high risk for cardiovascular disease should be screened as early as age 3 years. A high-risk child is one who has a family history of premature cardiovascular disease diagnosed at <55 years old for males (father or brothers) or <65 years for females (mother or sisters), a parent who has a serum cholesterol >240 mg per dL, or the child has risk factors, such as obesity, hypertension, diabetes, cigarette smoking, or moderate or high-risk conditions. The recommended screening is with either nonfasting non-HDL lipid profiles or fasting lipid profiles.11

• Genetics. Tracing the illnesses suffered by parents, grandparents, and other blood relatives can help the primary care physician predict the disorders to which a child may be at risk and take action to keep the patient and the patient’s family healthy. Family history (preferably a three-generation genogram) is the single most important genetic tool.

IMMUNIZATIONS

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), the Committee on Infectious Diseases of the American Academy of Pediatrics, and representatives from the American Academy of Family Physicians have worked together to develop the recommended childhood immunization schedule. Recommendations are updated annually and can be found at http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines. The following information is based on 2014 recommendations.12

• Hepatitis B. All children should be immunized against hepatitis B at birth, 1 to 2, and 6 to 18 months of life. Infants born to mothers positive for hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) should receive hepatitis B vaccine and hepatitis B immune globulin within 12 hours of delivery. Infants born to mothers with unknown HBsAg status should receive hepatitis B vaccine, and mother’s blood should be drawn; if positive for HBsAg, then immune globulin should be administered to the infant within 1 week of delivery. All older children and adolescents at high risk for hepatitis B infections should receive a complete series of immunizations.

• Rotavirus. This vaccine is available as a live attenuated rotavirus and is given as a liquid by mouth at 2, 4, and 6 months of age. The maximum age for the final dose is 8 months.

• Diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis. All children should be immunized against diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis (DTaP) at 2, 4, 6, and 15 to 18 months of age (the fourth vaccine can be given any time between 12 and 18 months, provided at least 6 months have passed since the third vaccination). This vaccine contains an acellular pertussis preparation that has fewer side effects than whole-cell pertussis preparations. If a child younger than 7 years has a contraindication to pertussis vaccine, DT should be used.

• Haemophilus influenzae type B. All children should be immunized against H. influenzae type B (Hib) at 2, 4, 6, and 12 to 15 months.

• Pneumococcal disease. All children should be immunized with the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13) at 2, 4, 6, and 12 to 15 months. Children aged 2 years and older who are at increased risk for Streptococcus pneumoniae infections (e.g., those with sickle cell disease, cochlear implants, HIV infection, and other immunocompromised or chronic medical conditions) who did not receive PCV13 should be vaccinated according to the high-risk schedule with PCV13 and PPSV23.

• Poliovirus. All children should be immunized against polio with the inactivated poliovirus vaccine (IPV) at 2 months, 4 months, 6 to 18 months, and 4 to 6 years of age. To eliminate the risk for vaccine-associated paralytic poliomyelitis, use of an all-IPV schedule is now recommended.

• Influenza vaccine. Influenza vaccine is recommended annually for all children aged 6 months and older, especially those with the following risk factors: asthma, cardiac disease, sickle cell disease, HIV, diabetes, and children who are household members of health care workers. Children receiving the inactivated influenza vaccine (IIV) should be given an age-appropriate dose (0.25 mL if aged 6 to 35 months and 0.5 mL if ≥3 years). Children ≤8 years old who are receiving the vaccination for the first time should receive two doses. Healthy children >2 years old can receive the live attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV).

• Measles, mumps, and rubella. All children should be immunized against measles–mumps–rubella (MMR) at 12 to 15 months and 4 to 6 years of age. For infants aged 6 to 11 months, administer one dose prior to any international travel, and for infants aged 12 months and older, administer two doses prior to departure, with the second dose 4 weeks after the first. MMR is a live attenuated viral vaccine.

• Varicella. All children who have no history of varicella infection should be given the varicella zoster vaccine (VZV) at 12 to 18 months of age. It is a live attenuated viral vaccine.

• Hepatitis A. All children should be immunized against hepatitis A, with the first dose at 12 months of age and the second dose 6 to 18 months after the first dose.

• Contraindications to vaccines in general include: Prior anaphylactic reaction to vaccine or any vaccine component (i.e., egg protein for influenza vaccine), and moderate or severe acute illness. Do not postpone vaccinations for mild illness, which become missed opportunities.13

ANTICIPATORY GUIDANCE AND COUNSELING

Providing anticipatory guidance and health education surrounding issues likely to be encountered at specific ages is a cornerstone of the pediatric health maintenance visit. Clinicians should be familiar with common parental questions and be prepared to provide counseling and advice about child development, child behavior, discipline, nutrition, and safety.

• Dental and oral health. Dental and oral health counseling should be provided routinely, with referral for a dental visit occurring at 2 to 3 years of age. Parents should be instructed to wipe their infants’ gums and teeth with a moist washcloth after each feeding. Once multiple teeth have appeared, parents should brush their infants’ teeth daily using a pea-sized amount of toothpaste. To prevent tooth decay, infants should not be permitted to fall asleep with a bottle containing anything other than water. Infants should be encouraged to begin using a cup instead of a bottle at age 1 year. Fluoride supplementation should be administered according to the following guidelines:

• Infants who are exclusively breastfed and those who live in an area without adequately fluoridated water should receive fluoride supplementation beginning at age 6 months and continuing until approximately age 16 years.

• Children who live in an area where the local water supply contains less than 0.3 parts per million (ppm) of fluoride should receive 0.25 mg fluoride daily until age 3 years, 0.5 mg fluoride daily from 3 to 6 years, and 1.0 mg daily from 6 to 16 years.

• Children who live in an area where the local water supply contains 0.3 to 0.6 ppm of fluoride require no supplementation until age 3. From age 3 to 6 years, they should receive 0.25 mg fluoride daily, and from age 6 to 16 years, they should receive 0.5 mg daily.

• No fluoride supplementation is required for children living in areas with more than 0.6 ppm of fluoride in the local water supply.1

• Safety. Age-specific safety counseling should be provided routinely. Among the safety issues to be addressed are the following:

• Sudden infant death syndrome: A sleeping infant should be positioned on his or her back and should not sleep prone.

• Car seats/booster seats: The AAP recommends that infants should be rear facing until 2 years old. Children should transition from a rear-facing seat and use a forward-facing seat with a harness until they reach the maximum weight or height for that seat. The next step is a booster seat, which will make sure the vehicle’s lap-and-shoulder belt fits properly. The shoulder belt should lie across the middle of the chest and shoulder, not near the neck or face. The lap belt should fit low and snug on the hips and upper thighs, not across the belly. Most children will need a booster seat until they have reached 4 feet 9 inches tall and are between 8 and 12 years old.14

• Use stair and window gates to prevent falls.

• Keep objects that can cause suffocation and choking away from small children.

• Avoid scald burns by reducing the water temperature of hot water heaters to below 120°F.

• Keep medicines and other dangerous substances locked up and in child-resistant containers.

• Always ensure that children wear safety helmets when riding bicycles.

• Smoke alarms should be installed and maintained in the home.

• If a firearm is kept in the home, it should be stored unloaded and locked away, separately from ammunition.

REFERENCES

1. Bright Futures. American Academy of Pediatrics. http://brightfutures.aap.org/. Accessed June 2, 2014.

2. Ages & Stages Questionnaire. Brookes Publishing Company. http://agesandstages.com/. Accessed June 2, 2014.

3. Newborn Screening Information. National Newborn Screening & Global Resource Center. http://genes-r-us.uthscsa.edu/. Accessed June 2, 2014.

4. McCandless S. A primer on expanded newborn screening by tandem mass spectrometry. Primary Care Clin Office Pract 2004;3:583–604.

5. Barlow SE; Expert Committee. Expert Committee recommendations regarding the prevention, assessment, and treatment of child and adolescent overweight and obesity: summary report. Pediatrics 2007;120(4):S164–S192.

6. Krebs NF, Jacobson MS; American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Nutrition. Prevention of pediatric overweight and obesity. Pediatrics 2003;112(2):424–430.

7. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Name/recommendations. Accessed January 30, 2015.

8. Spagnolo A, Giussani M, Ambruzzi AM, et al. Focus on prevention, diagnosis and treatment of hypertension in children and adolescents. Ital J Pediatr 2013;39:20. doi:10.1186/1824-7288-39-20.

9. Committee on Practice and Ambulatory Medicine, Section on Ophthalmology. American Association of Certified Orthoptists, American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus, American Academy of Ophthalmology. Eye examination in infants, children, and young adults by pediatricians. Pediatrics 2003;111(4, pt 1):902–907.

10. Potter B, Rindfleisch K, Kraus CK. Management of active tuberculosis. Am Fam Physician 2005;72(11):2225–2232. http://www.aafp.org/afp/20051201/2225.html. Accessed April 28, 2014.

11. Expert Panel on Integrated Guidelines for Cardiovascular Health and Risk Reduction in Children and Adolescents; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Expert panel on integrated guidelines for cardiovascular health and risk reduction in children and adolescents: summary report. Pediatrics 2011;128(5):S213.

12. Immunization schedules. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/schedules/index.html. Accessed June 2, 2014.

13. Chart of contraindications and precautions to commonly used vaccines. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/recs/vac-admin/contraindications-vacc.htm. Accessed June 2, 2014.

14. AAP updates recommendation on care seats. American Academy of Pediatrics. http://www.aap.org/en-us/about-the-aap/aap-press-room/pages/AAP-Updates-Recommendation-on-Car-Seats.aspx. Accessed June 2, 2014.

| Health Maintenance for Adolescents |

The adolescent health care visit is one of the best opportunities to impart preventive medicine, as most adolescents are healthy, and should be conducted yearly as the choices made during adolescence will result in consequences that may persist into adulthood.1 Three of four adolescents engage in risky behavior, with over 70% of adolescent deaths related to motor vehicle crashes, unintentional injuries, homicide, and suicide.2–4

This chapter will cover four elements of the adolescent health care visit; the history and physical, screening, immunizations, and counseling. Special emphasis is placed on screening, as this is the optimal time to diagnose and treat adolescents to promote health. Bright Futures is a national health promotion and disease prevention initiative from the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) that addresses children’s health needs in the context of family and community and is the basis for most recommendations in this chapter; their web site has many useful downloadable tools and resources.1 Table 1.3-1 summarizes preventive services discussed in this chapter for those aged 11 to 21 years.

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

The history portion of the adolescent exam differs slightly as adolescence is the time to begin allowing the child to take part in their care. It is important to outline the appointment for both the youth and the parent. Interviewing the parent to cover concerns followed by having the parent, friend, and/or partner leave the room to cover other aspects of the history without others present is crucial to proper risk assessment. Many youth may not divulge information in the presence of others. It is important to discuss confidentiality with the patient, so that he or she is assured that what they say will remain confidential.

While discussing sexuality or sexual practices, it is important to normalize this for the patient as well. Providers that appear uncomfortable with this discussion will promote discomfort with the patient. While interacting with the adolescent, providers should display respect for the youth, avoid assumptions, ask specific questions, avoid medical jargon, and listen to responses without interruption. Fostering the provider–patient relationship during adolescence will create a trusting relationship as the patient ages, enhancing health care for the patient.5

The health care maintenance visit during adolescence should focus on determining risks, such as obesity, high blood pressure, substance use, cardiovascular disease, and sexually transmitted disease. The exam should be complete with attention paid to signs of abuse or self-inflicted trauma. Laboratory testing or imaging should be based on the individual’s risk assessment, history, and physical exam.6

SCREENING

• Obesity and eating disorders. Adolescents should be questioned about body image and behaviors that may suggest an eating disorder. Excessive weight loss or gain may be a sign of anxiety or depression. Adolescents should be screened for obesity yearly. Obesity is defined as BMI greater than the 95th percentile for age and sex, and overweight is defined as BMI between the 85th and 95th percentiles, while underweight is BMI less than 5% for age and sex.7 Obese adolescents should be referred to counseling and behavioral interventions to promote improved weight status.7

• Hypertension. The goals for screening adolescents for hypertension are to identify primary versus secondary hypertension in order to potentially reverse the causes of secondary hypertension, identify those who need antihypertensive treatment, and identify comorbid risk factors in those found to have prehypertension or hypertension.1,6

The 2004 National High Blood Pressure Education Program Working Group definitions are used to classify blood pressure measurements in the United States. Blood pressure percentiles are based upon gender, age, and height. The systolic and diastolic pressures are considered equal, with the higher value determining the blood pressure category.

Systolic and diastolic blood pressures both below the 90th percentile are considered normal. Prehypertension is defined as systolic and/or diastolic pressures above the 90th percentile but below the 95th percentile or exceeding 120/80. If either the systolic and/or the diastolic pressure is over the 95th percentile, the patient is considered hypertensive. Hypertension is further delineated into stage I (mild) or stage II (severe). Stage I is defined as systolic and/or diastolic pressures between the 95th percentile and 5 mmHg above the 99th percentile. Stage II is defined as systolic and/or diastolic pressures 5 mmHg above the 99th percentile.8

Health Care Maintenance for Adolescents Aged 11 to 21 Years |

Condition | Recommendation |

Screening |

|

Obesity/eating disorders | BMI, screening questions |

Hypertension | Blood pressure |

Substance use | Screening questions |

Depression/suicide | Screening questions |

Abuse (physical, sexual, emotional) | Screening questions |

Learning/school problems | Screening questions |

Sexual behaviors | Screening questions; STI testing as indicated |

HIV | Screen one time ages 15–65 yr with HIV test |

Hearing | Screening questions about difficulty understanding and hearing; audiometry if positive |

Vision | Once during each age stage (11–14, 15–17, and 18–21) with Snellen chart |

Tuberculosis | Screening questions for risk factors; TST if positive |

Lipid disorders | Screen everyone between the ages of 9–11 and ages 18–21 and high-risk adolescents ages 12–17 with lipid profile |

Anemia | Screening questions about eating habits/menses; hemoglobin/hematocrit if positive |

Immunizations |

|

Influenza | Annually |

Tetanus–diphtheria–pertussis | Tdap ages 11–12 |

Human Papillomavirus | Ages 11–12 (three-dose series) |

Meningococcus | Ages 11–12; booster ages 16–18 |

Catch-up and high-risk conditions | Assess at each visit |

Counseling |

|

Dietary habits, obesity, eating disorders, regular exercise, strengthening exercises, screen time, tobacco, alcohol, drug use, sexual behaviors, contraception, injuries (helmets & seat belts), hearing loss, bullying/online activities, skin protection, and dental health | Periodically |

Secondary hypertension is more likely in adolescents that are prepubertal, those with stage II hypertension, or those with diastolic and/or nocturnal hypertension, which can be detected with ambulatory blood pressure monitoring. On the other hand, those more likely to have primary hypertension are postpubertal, have mild or stage I hypertension, are overweight, or have a significant family history of hypertension.8 Most adolescents, especially those likely to have secondary hypertension, may need to be referred to a specialist with experience in childhood hypertension or a pediatric nephrologist.

• Substance use. Adolescent youth should be asked about tobacco, drinking, or illicit drug use. If there is a positive response to questions regarding adolescent drug use, screening tools, such as the CRAFFT questionnaire found in Bright Futures documents, should be used for further evaluation.1

• Depression. Adolescence is a critical period for the development of depressive disorders; however, depression can be seen even in younger children. Depression occurs in 2.8% of children younger than 13 and in 5.6% of adolescents aged 13 to 18.6 The AAP recommends asking each youth directly about depression and suicide. There are a few tools that can be used by primary care physicians to screen for depression, including PHQ-2/PHQ-9, the Beck Depression Inventory, Reynolds Adolescent Depression Screen, and Mood and Feelings Questionnaire. The depression tools listed are a good start for screening, but results should be interpreted along with other information, such as that from parents or guardian.

• Suicide. Suicide is the third leading cause of death in children and adolescents. Suicidal ideation can occur in the prepubertal ages, although attempts and completions are rare.2 Increasing attempts and completion rates occur with increasing age. Female youth are more likely to have suicidal ideations, a specific plan, as well as attempts; however, males are more likely to complete suicide. Risk factors for suicidal behavior in children include psychiatric disorders, previous attempts, family history of mood disorders or suicidal behavior, history of physical or sexual abuse, and exposure to violence. Other questions to ask include potentiating factors, such as access to means, alcohol or drug use, exposure to suicide, social stress or isolation, as well as emotional or cognitive factors. Although potentiating factors do not contribute to suicide directly, they interact with risk factors, leading to more risky behaviors.9–11

• Physical, sexual, emotional abuse. Abuse is prevalent in the United States, with violence as a major cause of death and disability for American children. Victims and witnesses to abuse have both physical and psychiatric sequelae.12

Although school remains one of the safest places for youth, it is clear that violence is everywhere.11 Primary prevention is key for providers seeing youth in their practice, and they should screen for violence and other risk factors during all wellness exams.13 Risk factors for violence or violence-related injuries include previous history of fighting or violence-related injury, access to firearms, alcohol and drug use, gang involvement, and exposure to domestic violence, child abuse, media violence, and violent discipline. If a youth discloses abuse during the encounter, ensure safety for the youth and report all cases of child abuse.4,11

Screening for violence includes both a family assessment and an environmental assessment. Youth should be asked about family function, stress or coping mechanisms, and support systems. Environmental assessment includes screening for access to weapons, namely guns. Youth should be asked about school performance, as abrupt decline may be a sign of bullying, depression, abuse, or family stresses.4,11,14

• Learning or school problems. Learning disorders are not uncommon among children. Risk factors for developmental disorders include poverty, male sex, presence of smoke, being adopted, and having a two-parent stepfamily or other family structure. Adolescent youth should be asked about difficulties at school, including academic performance and interactions with peers, with further evaluation for diagnosis and treatment for those at risk.

• Sexual behavior. Middle adolescence (ages 14 to 17) is characterized by increasing sexual interests. The average age of coitus initiation in America is 16. As adolescents age, there are higher rates of sexual activity as well as higher rates of sexually transmitted disease acquisition. Nearly half of new sexually transmitted infections are diagnosed in individuals between the ages of 15 and 25.

To counsel youth effectively, it is important to discuss their sexual orientation (physical and/or emotional attraction to the same and/or opposite gender) and gender identity (person’s private sense or subjective experience of their own gender, generally described as one’s private sense of being a man or a woman). It is important not to assume individuals are heterosexual; as many as 10% of adolescent females and 6% of adolescent males report sexual encounters with the same sex.15

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree