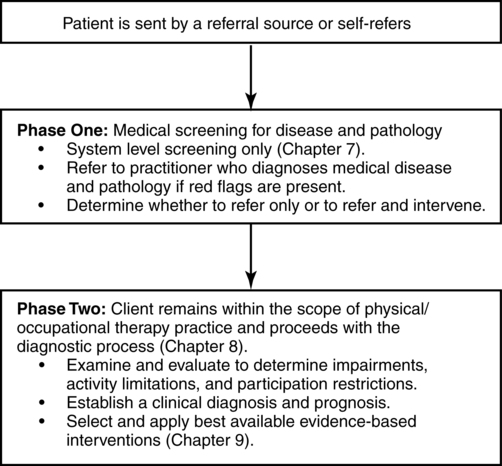

ROLANDO T. LAZARO, PT, PhD, DPT, GCS, MARGARET L. ROLLER, PT, MS, DPT and DARCY A. UMPHRED, PT, PhD, FAPTA After reading this chapter the student or therapist will be able to: 1. Differentiate the medical diagnosis made by the physician from the diagnosis made by a movement specialist. 2. Identify the differences among activity limitations, participation restrictions, and impairments in specific body structure and function. 3. Choose appropriate examination tool(s) from each category of the ICF model—body system problems and impairments, activity limitations, and participation restrictions. 4. Identify resources used to analyze the usefulness and psychometric properties of outcome measures that address body system impairments, activity limitations, and participation restrictions. 5. Discuss the role of support personnel and assistants in the examination process. 6. Evaluate the results of the clinical examination to establish a therapy diagnosis that drives intervention planning. Since the beginning of the evolution of practice for movement specialists within the health care arena, clinicians have been expected to examine a client’s functional performance and draw conclusions from the examination. The synthesis of information gathered has led to the establishment of short- and long-term goals, a prognosis concerning the likelihood of the goals being achieved, and the time it will take to achieve those goals. Similarly, the selection of the most effective and appropriate intervention strategies will guide the therapist and patient toward the desired outcomes. Today, clients are referred for physical and occupational therapy with “evaluate and treat” orders as the common referral pattern used by physicians or other health care providers. With direct access to physical and occupational therapy becoming a reality in many states across the United States and other countries, many patients are walking into clinics because they have decided that therapy is the best alternative to assist with their functional problems. Whether through self-referral or referral from another medical or health care practitioner, once a client enters into a therapeutic environment, clinicians must first determine whether the individual is medically stable at a body system level (see Chapter 7) and an appropriate candidate for therapeutic intervention. Once medical screening has been completed and the therapist determines that there are no red flags to suggest that the client needs to be referred for additional disease or pathology examination or does not need therapeutic intervention, then the client enters into Phase 2 of the evaluation process (Figure 8-1). In this phase it is important to examine and identify the client’s strengths that will facilitate recovery of functional movement, as well as what the client is unable to do functionally. To be able to provide information that is meaningful in determining the best possible intervention for a particular patient, the examination tools selected by the clinician must be objective, reliable, valid, and appropriately matched with patient expectations. These tools should also communicate necessary information in a language that is understandable to all health care professionals and the payer responsible for funding the services (see Chapter 10). With the limitations on visits within the clinical setting and the critically important variable of motivation and adherence of the patient, the setting of goals and the selection of intervention strategies need to be established through patient-centered participation.1–10 This chapter has been developed to help the reader work through the problem-solving and decision-making process for selecting appropriate tests. It is not within the scope of this chapter or text to explain each examination tool in detail. However, the reader is presented with an extensive list of tests for body function and structure, activity, and participation in Appendix 8-A. Impairment (ICF; International Classification of Impairments, Disabilities, and Handicaps [ICIDH]; Nagi)11 is defined as the loss or abnormality of physiological, psychological, or anatomical structure or function at the organ system level.12 The clinician needs to make the distinction between primary impairments, which are a direct consequence of the client’s specific disease or pathological condition, and secondary impairments, which occur as sequelae to the disease or rehabilitation process or as the result of aging, disuse, repetitive strain, lifestyle, and so on. Moreover, the clinician must remember that, although functional limitations are usually caused by a combination of specific impairments, it is possible that impairments may not contribute to specific functional problems for a particular client. If this is the case, the clinician should make a determination regarding whether these impairments, if left uncorrected, will result in the development of activity limitations at a later time. Simultaneously, the patient needs to be a part of this discussion because the therapist may not have the time to address all impairments. The correction of particular impairments may have more meaning or value to the patient. To the consumer some impairments may lead to limitation of functions that are important to them, whereas other impairments may restrict an activity in which the patient would never want to participate. Box 8-1 illustrates impairments that may be seen in patients/clients with movement disorders caused by neurological dysfunctions. These impairments are further classified as those that are within the central nervous system and those that are outside the central nervous system and result from interaction with the environment. These impairments are further discussed in detail in various sections of this book. Range of motion testing is one example of a common neuromusculoskeletal system examination procedure. Clinicians depend heavily on ROM measurements as an essential component of their examination and consequent evaluation process. It is imperative that the data obtained from this procedure be reliable. It has been suggested that the main source of variation in the performance of this procedure is method and that reliability can be improved by standardizing the procedure.13 The status of the cardiac, respiratory, and circulatory systems significantly affects a client’s functional performance (see Chapter 30). Blood pressure, heart rate, and respiration give the clinician signs of the patient’s medical stability and the ability to tolerate exercise. The clinician may also obtain the results of pulmonary function tests for ventilation, pulmonary mechanics, lung diffusion capacity, or blood gas analysis after determining that the client’s pulmonary system is a major factor affecting medical stability and functional progress. Various exercise tolerance tests also attempt to quantify functional work capacity and serve as a guide for the clinician performing cardiac and pulmonary rehabilitation. A client who has difficulty performing activities of daily living and who has neurological impairments in the central motor, sensory, perceptual, or integrative systems needs to undergo examination procedures to establish the level of impairment of each involved system and to determine if and how that system is contributing to the deficit motor behaviors. Functional evaluation tools used may include the FIM, the Barthel Index, the Tinetti POMA, or the TUG test. The results of these tests will help to steer the clinician toward the most useful impairment tools to use to evaluate limitations in the various body systems. Impairment tools may include the Modified Ashworth Scale for spasticity, the Upright Motor Control Test for lower-extremity motor control, the Clinical Test of Sensory Interaction on Balance (CTSIB), or the Sensory Organization Test (SOT) for balance and sensory integrative problems, or computerized tests of limits of stability on the NeuroCom Balance Master, among others (see Appendices 8-A, 8-B, and 8-C). The clinician is also advised to investigate the interaction of other organs and systems as they relate to the patient’s functional limitations. For example, electrolyte imbalance, hormonal disorders, or adverse drug reactions (see Chapter 36) may explain impairments and activity limitations noted in other interacting systems. In ICF terminology, participation is defined as an individual’s involvement in a life situation. Domestic life, interpersonal interactions and relationships, and community, social, and civic life are some examples of aspects of participation that can be examined for each individual. Participation restriction is the term used to denote problems that individuals may experience in involvement in life situations. When considering participation it is important to obtain the individual’s perception of how the medical condition, impairments, and activity limitations affect his or her involvement in life and community. Therefore many of the tests for participation and self-efficacy are in self-report format. The Activities-specific Balance Confidence Scale (ABC), Short Form 36 (SF-36), and Dizziness Handicap Inventory (DHI) are examples of tests that can be used to gather information under this domain. These tests allow an individual to assess his or her health quality of life after an incident that affected activity and participation. Appendices 8-A, 8-B, and 8-D include tools that measure participation and quality of life. 1. The client’s current functional status (ambulatory vs nonambulatory) 2. The client’s current cognitive status (intact vs confused or disoriented) 3. The clinical setting in which the person is being evaluated for treatment (acute hospital, rehabilitation, outpatient, skilled care, or home care) 4. The client’s primary complaints (pain vs weakness vs impaired balance) 5. The client’s goals and realistic expectation of recovery, maintenance, or prevention of functional loss (acute injury, chronic problem, or progressive disease process) 6. The type of information desired from the test (discriminative or predictive) Many of the examination tools that measure a client’s ability to perform functional activities have been accepted as valid, reliable, and useful for the justification of payment for services rendered. The number of activity limitations and the extent of the client’s participation limitation are often reasons why an individual either has accessed therapy services directly or was referred by a medical practitioner. For this reason, the third-party payer expects to receive reports concerning positive changes in the client’s functional status for therapeutic services to be justifiable (see Chapter 10). The initial list of functional or activity limitations or participation restrictions helps the therapist determine the extent of, expectations for, and direction of intervention, but it does not determine why those limitations exist. This is the question that is critical to answer as part of the evaluation process. Examination tests and procedures that identify specific system and subsystem impairments help the therapist determine causes for existing participation and activity limitations. These tools need to be objective, reliable, and sensitive enough to provide needed communication to third-party payers to explain the subsystem’s baseline progress during and after the intervention. These tools should also supply explanations for residual difficulties in the event that the functional problems themselves do not demonstrate significant objective change or show progress within the time frame estimated. Assume that a clinician has been called in to examine a client who has sustained an anoxic brain injury during heart surgery. The client’s cognitive ability is within normal limits, and he is highly motivated to get back to his normal activities. He is retired; he loves to walk in the park with his wife and to go on birdwatching experiences in the mountains with their group of friends. The clinician must select which functional tests to use to obtain an objective initial status and target the client’s problems. Currently the client requires assistance with all gross mobility skills and is demonstrating difficulty balancing in various postures and performing activities of daily living. Results of functional testing reveal that the client demonstrates significant limitations, requiring moderate assistance in the activities of coming to sit, sitting, coming to stand, standing, walking, dressing, and grooming. Assume that the client also displays impairment limitations in flexion ROM at the hip joints caused by both muscle and fascia tightness and hypertonicity within the extensor muscle groups. He has compensated to some degree and is able to perform bed mobility independently. Upper-extremity motor control is within normal limits, and thus the client is capable of performing many activities of daily living as long as his lower trunk and hips are placed in a supportive position and hip flexion beyond 90 degrees is not required. The client has general weakness from inactivity, and power production problems in his abdominals and hip flexor muscles owing to the dominance of extensor muscle tonicity. Once he is helped to stand, the extensor patterns of hip and knee extension, internal rotation, slight adduction, and plantarflexion are present. He can actively extend both legs after being placed in flexion, but he is limited in the production of specific fine and gross motor patterns. Thus a resulting balance impairment is present owing to the inability to adequately access appropriate balance strategies caused by the presence of tone, limb synergy production, and weakness in the antagonists to the trunk and hip extensors. Through the use of augmented intervention (see Chapter 9) the client is noted to possess intact postural and procedural balance programming; however, both functions are being masked by existing impairments. The decision is made to perform impairment measures, including assessments of ROM at the hip, knee, and ankle joints; the ability to produce strength in both the abdominal and hip flexor muscle groups; and volitional and nonvolitional synergic programming, balance, and posture, and volitional control over muscle tone. The demand on ROM, power production, and specific synergic programming will vary according to the requirements of the functional activities performed. Scores obtained from tests of activity, participation, and impairments supply statistically important measurements that can then be used to discuss the limitations placed on the therapeutic environment by fiscal intermediaries. Therapists must be clear when documenting the initial status and the target status for clients so that the recommended intervention and length of stay may be justified (see Chapter 10).

Differential diagnosis phase 2: examination and evaluation of functional movement activities, body functions and structures, and participation

Tests of body functions and structures

Tests for participation and self-efficacy

Choosing the appropriate examination tool

Using the evaluation process to link body system problems, activity limitations, and participation restrictions to intervention

Differential diagnosis phase 2: examination and evaluation of functional movement activities, body functions and structures, and participation