Chapter 48 Delirium and Dementia

Delirium

Clinical Features

Delirium prevalence and incidence vary greatly across settings of care and populations served. From 10% to 15% of hospitalized elderly patients have delirium on admission, and another 5% to 10% develop it during their stay. More than half of long-term care residents will exhibit delirium on hospital admission. Postsurgical patients (e.g., hip fracture, cardiac surgery) and elderly patients cared for in an intensive care unit (ICU) are at particularly high risk (Khan et al., 2009).

Etiology

The remainder of this discussion focuses on delirium in the elderly patient.

Neurochemical Hypothesis

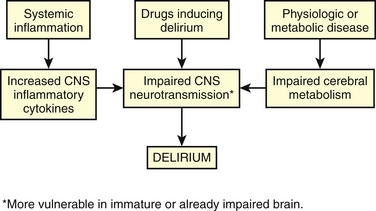

Cholinergic transmission in the CNS has a major role in cognition and attention, and an acute cholinergic deficit exists in delirium. Dopaminergic transmission is increased in delirium, and this or the imbalance between cholinergic and dopaminergic systems may be etiologic. Disturbances in other neurotransmitters are hypothesized, perhaps explaining subtypes or variations in presentations of delirium. Serotonin may be increased in delirium associated with serotonin syndrome and in hepatic encephalopathy, but decreased in delirium from other causes. Glutamate and γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) are believed to be increased in alcohol withdrawal and hepatic encephalopathy. Melatonin may be increased or decreased in delirium, which may explain hypoactive and hyperactive subtypes. Norepinephrine may be increased in delirium associated with anoxia and in hepatic encephalopathy. Inflammation may also play a role in causing delirium, either by a direct neurotoxic effect or by causing disturbances in the neurotransmitters. Figure 48-1 depicts a theoretic explanation for the etiology of delirium.

Diagnostic Process

Diagnostic criteria for delirium are adapted from the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition, text revision (DSM IV-TR, 2000) (Box 48-1). Given the high prevalence of delirium in certain health care settings and clinical circumstances, diagnosis should not depend solely on a high index of suspicion. Formal evaluation of mental status to detect delirium or dementia should become part of routine assessment of elderly patients presenting with a change of condition. This not only fosters appropriate preventive and therapeutic interventions, but also alerts the interdisciplinary team (IDT) to plan care to ensure patient and staff safety, specific patient and family education, carefully considering cognition and function at discharge planning.

Box 48-1 Diagnostic Criteria for Delirium (DSM IV-TR)

Modified from American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed, text revision. Washington, DC, APA, 2000.

History and Physical Examination

Severe illness, infections, sensory deprivation, medications, and substances of abuse causing either toxicity or withdrawal states can precipitate delirium. Use of medications confers risk both by number and by drug interaction. The risk of delirium is especially high in elders who have three or more medications initiated within a 24-hour period during hospitalization. Box 48-2 is a compilation of predisposing and precipitating risks for delirium, and Boxes 48-3 and 48-4 list medical illnesses and drugs, respectively, that can cause or contribute to delirium.

Box 48-3 Medical Conditions that May Cause or Contribute to Delirium

Box 48-4 Drugs that May Cause or Contribute to Delirium

From American Medical Directors Association. Delirium and Acute Problematic Behavior Clinical Practice Guideline. Columbia, Md, AMDA, 2008.

Other investigations may be needed in specific situations. An EEG is not routinely needed but is helpful in diagnosing toxic encephalopathy, and it is essential in a patient with suspected nonconvulsive status epilepticus.

Prevention

An evaluation of risk allows caregivers to apply preventive strategies to avoid development of delirium in high-risk individuals (Box 48-5). However, given the high prevalence in hospitalized elderly patients and in long-term care patients, and the benign nature of many of the strategies for prevention, a standardized facility-wide prevention program may be more appropriate and effective. Prevention involving nonpharmacologic strategies attempts to maintain or normalize sleep patterns, stimulate physical and mental activity consistent with the elderly person’s function, maintain or restore orientation to time/person/place, avoid or correct fluid and electrolyte disturbances, maximize the accuracy of sensory perceptions, and minimize the use of catheters and physical restraints.

Box 48-5 Prevention and Treatment Strategies for Delirium

Treatment

Treatment of delirium begins with maximized effort to apply strategies outlined in Box 48-5. Identifying and treating one or more potential causes of delirium are equally important (e.g., correcting fluid and electrolyte imbalance, treating an infection and discontinuing medications conferring risk). Many delirium-induced behaviors respond well to nonpharmacologic interventions. For example, a delirious elderly patient with repetitive vocalizations disturbing others should be managed by protecting others from the noise, not by sedating the delirious patient. Having a family member or sitter stay with a restless patient is better than use of physical or chemical restraints.

KEY TREATMENT

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree