Cruciate-Retaining Total Knee Arthroplasty

Michael E. Berend

Trevor R. Pickering

The decision to retain and balance the posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) or remove it and substitute it with a prosthetic interface is an important and somewhat controversial choice in total knee arthroplasty (TKA). PCL substitution in general has been associated with increased articular constraint in TKA. Kinematics in a cruciate-retaining (CR)-TKA are not directed by the prosthesis but rather by the ligaments and dynamic forces about the knee and have been shown to facilitate long-term survivorship of knee replacements with a very low incidence of aseptic loosening (1, 2, 3, 4). We believe that retaining the PCL is possible in almost all TKAs and highly depends on surgical technique to sufficiently “balance” the kinematics of the knee. This chapter describes the principles behind a CR-TKA.

INDICATIONS AND CONTRAINDICATIONS

CR-TKA can be considered for virtually all primary TKAs. Although a knee that has sustained a “dashboard”-type injury in a motor vehicle accident and has an incompetent PCL may require a posterior-stabilized implant to achieve stability in the anterior/posterior (AP) plane, we have found this scenario to be quite rare. We have no firm contraindications for using a CR implant in a primary TKA. It was once thought that patients with inflammatory arthropathies should be excluded from consideration for a CR implant. Our vast experience with this population, however, has shown CR-TKA to have an excellent long-term outcome (see Results section below). Even knees with a lax PCL to start with can be balanced with a CR-TKA. Surgeons can use a CR implant for revision TKA as long as soft tissue balancing is meticulous and stability is rigorously evaluated during trialing. Many revisions require a greater degree of constraint secondary to ligamentous laxity or bony deficiency on the tibia and femur. Obviously, CR-TKA is not an option in these patients.

PREOPERATIVE PREPARATION

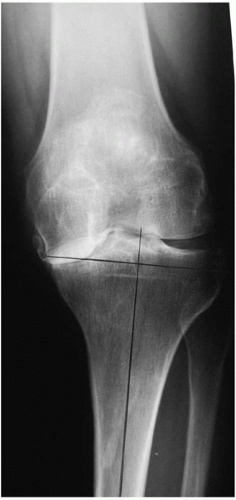

Preoperative planning includes determining coronal deformity on standing radiographs. Further, a detailed assessment of range of motion, flexion contracture, and ligament balance should be undertaken. Our surgical plan begins with marking a tibial cut that is perpendicular to the anatomic axis on the AP radiograph of the knee (Fig. 6-1). The location of the anatomic axis relative to the tibial spines becomes a proximal landmark for the extramedullary tibial cutting jig (Fig. 6-2). This helps prevent a varus tibial cut. Preoperative radiographs can also help the surgeon assess the need for augments, screws, or bone graft in cases with significant tibial defects. Sizing of the components with templates can also be done preoperatively on radiographs, although we have not found this to be as accurate as intraoperative assessment using osseous landmarks.

Knees with significant coronal and sagittal deformity often necessitate ligament releases of the concave side of the deformity. This may include combined releases of the medial or lateral and posterior structures, including the PCL. Preoperative planning for these deformities may better prepare the surgeon for the intraoperative findings.

Surgical technique is critical for the short- and long-term performance of a TKA, regardless of design (5). The principles of exposure, deformity correction, bone preparation, collateral ligament balancing, implant positioning, PCL balancing emphasizing flexion kinematics, and implantation are discussed in this chapter.

SURGICAL TECHNIQUE

Exposing the knee is the first step to effective deformity correction and appropriate implant position. A CR-TKA can be implanted with traditional and proven approaches such as a medial parapatellar arthrotomy of various lengths of quadriceps tendon split or with so-called, less invasive, techniques such as midvastus and sub-vastus exposures (6). We believe visualization can be adequately achieved with retention of the PCL in all knees.

We reflect the medial sleeve of the knee including the deep medial collateral ligament (MCL) in the vast majority of knees with a periosteal elevator. This is done with care to protect the superficial MCL and the pes anserine insertion. The surgeon excises the fat pad, which facilitates exposure. Fat pad removal has little effect on long-term outcome of TKA (7). Knee flexion follows with division of the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) and the anterior horn of the lateral meniscus to facilitate patellar subluxation. We have made smaller incisions over the past few years, as instruments have been refined for smaller exposures, and we now utilize patellar subluxation rather than patellar eversion.

FIGURE 6-3 Extramedullary tibial cutting guide. The external rod should overlie the center of the ankle distally. |

FIGURE 6-4 This system uses the ASIS bilaterally to locate the center of the hip on the operative side, which is then used to establish the mechanical axis of the knee. |

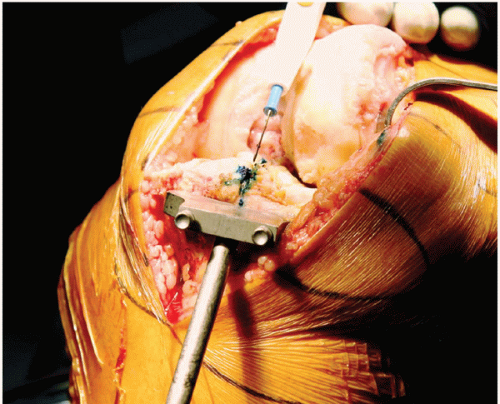

We cut the tibia first in most primary PCL-retaining TKAs. The surgeon uses an extramedullary guide to check the tibial cut with reference to the center of the ankle (Fig. 6-3). Tibial alignment has been shown to be an important factor in the long-term survivorship of TKA tibial components (5,8,9). Preoperative planning may help aid in determining the relative resection level of the medial and lateral tibial plateaus based on preoperative deformity. This may vary for varus and valgus patterns of arthrosis. A 90-degree templated resection level may help not only with positioning of the central portion of the cutting jig but also with determining tibial component rotation (Fig. 6-2). A pelvic-based reference system may also aid in external alignment of the center of the hip (Fig. 6-4) (10). Most CR-TKA implant systems have a greater amount of tibial slope built in relative to PCLsacrificing systems. If not, we recommend increasing the slope of the tibial cut by 2 to 3 degrees in order to ensure that the flexion gap will not be too tight. Once the tibial cut is completed, we have found that a confirmatory check of alignment with a flat tibial plate and an extramedullary rod helps identify and prevent a varus tibial cut (see Fig. 6-6).

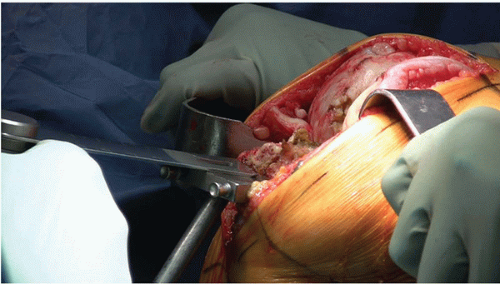

We use intramedullary femoral cutting jigs when possible. With retained hardware or significant distal femoral deformity, we use extramedullary jigs and a soft tissue tensioning device. Smaller distal cutting jigs are available, which facilitate less invasive surgical approaches. We cut the distal femoral valgus angle between 4 to 6 degrees in most knees with a measured resection technique, which correlates with the distal thickness of the implant (Fig. 6-5). In the presence of significant flexion contracture, an additional 2 mm of bone is removed for each 9 degrees of flexion contracture,

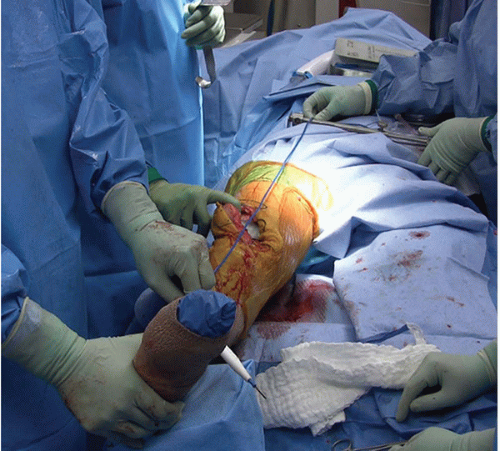

as described by Bengs and Scott (11). With the tibial and distal femoral cuts completed, the knee can be extended, and a spacer block or flat tibial plate with an extramedullary rod is used to check the mechanical alignment of the leg (Fig. 6-6

as described by Bengs and Scott (11). With the tibial and distal femoral cuts completed, the knee can be extended, and a spacer block or flat tibial plate with an extramedullary rod is used to check the mechanical alignment of the leg (Fig. 6-6

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree