Chapter 45 Crisis Intervention, Trauma, and Intimate Partner Violence

Development of Crisis Intervention, Trauma, and Disaster Theory

Historical Considerations

Eric Lindemann (1944) applied and expanded Salmon’s theories. He studied the acute grief reactions of persons who lost family members in the Coconut Grove fire in Boston, which claimed 500 lives. Lindemann discovered that normal people surviving such a horrific experience would develop an emotional crisis of pain, confusion, anxiety, and temporary difficulty in daily functioning. Also, he discovered that the psychological trauma caused by the crisis had little relation to preexisting psychopathology, and that only a small group of the victims declined to a lower level of functioning. Generally, the outcome of the crisis was most closely related to the severity of the stressor, personal reaction to the trauma, effect of trauma on the person’s family and friends, and degree of community disruption. Lindemann found that most crisis survivors recovered spontaneously within 6 weeks.

Current Understanding of Crisis

Intimate Partner Violence

Health Effects

Intimate partner violence leads to significant morbidity and mortality and contributes to high health care costs. Victims of IPV experience similar problems as patients with general crisis or trauma (Box 45-1). Abused U.S. women show increased rates of poor general health, digestive problems, abdominal pain, urinary and vaginal infections, pelvic pain, sexual dysfunction, headache, and chronic pain (Campbell, 2002). In particular, these women suffer from gynecologic, central nervous system (CNS), and stress-related problems at an increased rate of 50% to 70% (Wathen and MacMillan, 2003). The largest difference between sexually abused and non–sexually abused women is in gynecologic complaints. In addition to direct harm caused by trauma, perinatal complications include low birth weight, antepartum hemorrhage, labor complications, preeclampsia, and mental health problems in the mother (Cherniak et al., 2005).

Evaluating the Crisis or Disaster

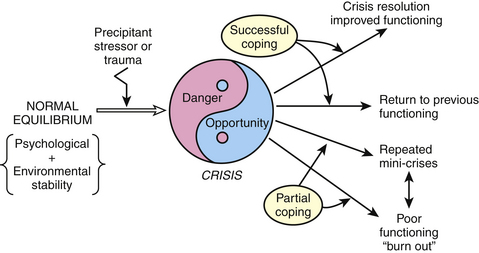

Figure 45-1 presents an overview of a modern crisis intervention theory that is useful for the treatment of a crisis, IPV, or trauma.

Normal Equilibrium State and Stressors

Hobson and associates (1998) revised the Holmes and Rahe (1967) social readjustment scale. This newer scale lists 51 external life stressors that precipitate significant stress in most people. The top 20 items in this scale were in five separate domains: death and dying, health care issues, stress related to crime and criminal justice system, financial and economic issues, and family stresses. This scale includes events that range in severity from the most stressful being death of a spouse (rated as 1), divorce (7), experiencing domestic violence or sexual abuse (11), and surviving a disaster (16). It also includes events that many would consider positive yet stressful, such as getting married (32), experiencing a large monetary gain (42), and retirement (rated as 49). This list of stressors represents the most common precipitants causing a crisis. It is these types of stressors, and the internally disturbing feelings attached to the event, that produce emotional turmoil and a transient inability to adapt during the early stages of a crisis.

Crisis State

Often, patients in a crisis or suffering from a trauma present to their family physician with a confusing array of physical complaints. Patients like Melinda, who seek help while in an acute crisis, are typically impaired in some aspect of their daily interpersonal, work, social, or family life. Patients may have obvious psychological symptoms, unconscious psychological distress and pain associated with substance abuse, or physical symptoms. Four clusters of symptoms are typically experienced by patients during a crisis or secondary to a trauma (Box 45-1).

Frequently, people in the crisis do not seek help by themselves and instead are brought in by concerned family members, lovers, friends, or perhaps the police or an ambulance. In these cases, it may take hours for the “Why now?” causes to be identified. Patients typically are not able to identify the specific cause of their crisis. Physician questioning and asking patients to retell their experience is typically how the “Why now?” of the crisis emerges. “Why now?” questioning is the first step in treating a crisis.

Acute Crisis Resolution and Adaptation to the Crisis (Within 6 Weeks)

For many patients, the acute nature of the crisis is often resolved within 6 weeks as the patient learns to cope or adapt to the acute stress. The DSM-IV-TR (APA, 2000) has classified the initial 1-month period of a crisis marked by impaired functioning as an “acute stress disorder.” DSM IV-TR specifies that the acute symptom picture must last more than 2 days and no more than 4 weeks and must cause significant distress or impairment in social or occupational functioning. The result of the acute stages of the crisis is one of four possible outcomes specified in Figure 45-1. Successful coping and adaptation to a crisis can lead to crisis resolution that ultimately promotes growth and can even lead to improved functioning. For most patients, however, crisis resolution means a return to a previous level of baseline functioning. Still other patients only partially resolve the crisis and instead “seal over” and deny the significance of their feelings or recent events, setting the stage for a future crisis. Those with the worst prognosis typically have poor adaptation skills and, at best, stabilize at a lower level of daily functioning. For example, a patient who swallowed many pills after being left by her boyfriend may in retrospect deny any suicidal intent and instead say, “I just had a headache.” This patient has sealed over her crisis. Denial of her suicidal intent and anger with her boyfriend will probably lead to poor adaptation and latent weakness, called a missed or unresolved crisis. The patient may continue to use unsuccessful coping strategies, such as drinking or repeated suicide gestures, as a way to deal with her feelings. Unresolved crises predispose the patient to future episodes that may be caused by even less stressful precipitants. For example, this same patient may once again become suicidal after a minor argument with a male friend. Fortunately, future crises can afford new opportunities to rework past unresolved crisis, with better adaptation and coping.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree