Chapter 40 Cranial remolding orthoses

The term plagiocephaly derives from the Greek plagios, meaning oblique, and cephalo, referencing the head.16 Plagiocephaly has been used in the medical literature to refer to both synostotic (i.e., craniosynostosis) and nonsynostotic (i.e., deformational) conditions.

Pathophysiology

The pathogenesis of cranial deformities arises from three primary causes: (1) abnormalities in brain shape or development, (2) abnormalities in bone or suture development, and (3) prenatal and postnatal deforming forces.7,12 Abnormalities in brain shape or development include conditions such as microcephaly, macrocephaly, and in utero cerebrovascular accident. Craniosynostosis involves premature fusion of one or more cranial sutures, and genetic disorders such as Apert syndrome and Crouzon syndrome produce significant alterations in bone and suture development. The largest group of patients seen for orthotic cranial remolding procedures presents with cranial deformities secondary to prenatal and postnatal deforming forces.

Cranial deformities often begin with restrictive in utero environments. Fetal constraint may be due to multiple births, a large fetus, first pregnancies, or sustained abnormal positioning secondary to conditions such as oligohydramnios, breech positioning, or early descent into the maternal pelvis. Vaginal deliveries produce significant distortion of the fetal cranium as it passes through the birth canal, and prolonged labor and difficult deliveries exacerbate the deforming forces. Cesarean deliveries may be performed due to cephalopelvic disproportion, sustained abnormal positioning, or a developing medical crisis in the fetus or mother. Any of these situations creates deforming forces that act on the developing fetal skull.5,6,32

Premature infants are extremely susceptible to cranial deformation due to the increased plasticity of the underdeveloped cranial structures. Extended periods of lying on the side and back in neonatal intensive care units may exacerbate cranial deformation. Term infants are also subject to postnatal forces that act on the cranial structures during supine positioning, which became the sleeping position recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) in 1992.1 The 1992 implementation of the “Back to Sleep” program was extremely successful in decreasing the incidence of sudden infant death syndrome; however, a corresponding increase in cranial deformities has been well documented.2,22 Another variable is the influence of congenital muscular torticollis and neck muscle asymmetry, a common finding in young infants, specifically those with deformational plagiocephaly.6,11,13,19,43 Unilateral neck involvement results in sustained head positioning that produces asymmetrical loading on developing cranial structures. Structural anomalies, such as cervical hemivertebrae, also contribute to skull deformity.

Ultimately, any combination of the following factors may produce or exacerbate cranial deformation: deforming forces in utero, deforming forces during the birth process, sustained supine positioning in compliance with the AAP Back to Sleep program, sustained supine positioning in neonatal intensive care units, sustained supine positioning during normal daily infant/caregiver routines, torticollis, and lack of education and information provided to caregivers relative to the importance of supervised prone positioning. In general, cranial distortion in the newborn is common and often resolves within the first 12 weeks of life if external forces acting on the skull are consistently altered. A cranial deformity usually is considered for orthotic intervention when the infant’s abnormal skull proportion and/or symmetry remains or fails to improve despite early intervention of repositioning and/or therapeutic efforts during the first 3 months after birth (Table 40-1).2,6,13,32,37

Table 40-1 Common clinical observations and classification of skull deformities

| Deformational Plagiocephaly | Deformational Brachycephaly | Deformational Scaphocephaly |

|---|---|---|

| Asymmetry of the neurocranium and viscerocranium: | Disproportion of the neurocranium and viscerocranium: | Disproportion of the neurocranium and viscerocranium: |

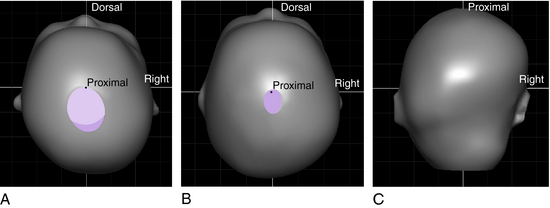

Three common presentations of cranial deformation are identified and treated with cranial remolding orthoses. Common clinical observations and classifications of skull deformities are detailed in Table 40-1, although many variations of the patterns of deformation exist. Deformational plagiocephaly is the most common cranial anomaly and presents with asymmetry of the right and left sides of the skull and face. Unilateral occipital flattening produces varying degrees of ipsilateral anterior ear displacement, ipsilateral forehead bossing, contralateral forehead flattening, and contralateral posterior occipital bossing. Facial structures are commonly affected, as evidenced by altered alignment of the eyes, cheeks, nose, mouth, and chin.

Deformational (symmetrical) brachycephaly and deformational scaphocephaly are less common and present with primary disruptions in cranial proportion (Fig. 40-1). Deformational symmetrical brachycephaly is clinically identified by central occipital flattening, increased cranial width, decreased cranial length, increased cranial vault height, and increased forehead bossing. A large number of infants have characteristics common to both plagiocephaly and brachycephaly and present with an asymmetrical brachycephalic head shape deformity. These infants require a complex treatment approach that addresses the asymmetry and disproportion. Deformational scaphocephaly presents with bilateral parietal flattening, increased cranial length, decreased cranial width, and occipital and anterior forehead protrusion or bossing. Secondary asymmetry of varying degrees may accompany either of these deformities (Figs. 40-2 and 40-3)

Evaluation of cranial deformity includes consideration of the following elements:

Historical perspective

History has shown many different applications of intentional cranial deformation. Different cultures applied a variety of measures to alter the shape of the infant skull. Boards, vines, cloth bandages, and even the weight of stones were applied to the head of the infant to create a culturally desired cranial shape. Even these primitive cultures recognized that early and sustained application of these intentional and specific forces would produce long-standing changes in cranial shape. Globally, skulls were elongated, flattened, rounded, widened, or contoured for a variety of reasons,33 yet all cultures opted for symmetrical distortion to meet some form of societal norm or distinction.

In 1979, Clarren et al.6 were the first to report on deformational plagiocephaly and orthotic treatment as a result of their experiences at the Dysmorphology Clinic of the University of Washington in Seattle. At that time, most infants who presented with dysmorphology or craniofacial clinics were diagnosed and surgically treated for many different congenital or hereditary disorders of the developing brain, bone, or suture(s). Cranial remolding orthoses were being used postoperatively to provide both protection and continued reshaping of the skull once the growth impedance of the fused suture was removed. Infants diagnosed with deformational plagiocephaly, brachycephaly, and scaphocephaly were the exception. Clarren et al. reported on 10 infants diagnosed with nonsynostotic plagiocephaly who were treated with cranial remolding orthoses. The treatment concept was based on knowledge of intentional cranial deformation and understanding of resistive forces and directed growth within the confines of a symmetrical orthosis.

In the early to mid-1990s, the significant increase in the number of infants who presented with asymmetrical and disproportional skull deformities coincided with the AAP Back to Sleep program.2,22 Craniofacial clinics experienced an overwhelming increase in the number of pediatric referrals. These specialty clinics were burdened by a large number of infants referred for suspected craniosynostosis when, in fact, they had deformational skull anomalies and were not actually surgical candidates. Particular confusion existed over the diagnosis of deformational plagiocephaly versus unilateral lambdoid synostosis, a relatively rare condition. Huang et al.18 outlined specific anatomical features found during clinical evaluation that distinguished deformational plagiocephaly from synostotic plagiocephaly. Evaluation from the vertex view reveals asymmetry and unilateral occipital flattening in both conditions. In this same view, deformational plagiocephaly presents with a parallelogram shape and anterior advancement of the ear on the same side as the occipital flattening. In contrast, from the vertex view, unilateral lambdoid synostosis presents with a trapezoid shape and posterior displacement of the ear on the same side as the occipital flattening. Other distinguishing features have been discussed in detail previously (Fig. 40-4).18

Current issues

The natural history of untreated deformational skull deformities has not been thoroughly studied. A study conducted at the Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta found that infants treated with cranial remolding orthoses showed significant improvement in symmetry measures, whereas the majority of untreated infants with deformational plagiocephaly showed changes in parameters related only to growth, not symmetry.37 The impact on the functional competence of adjacent structures relating to hearing, vision, balance, mandibular symmetry, and brain development has only recently been addressed with more rigorous scientific investigation.23,25,30,34 Many infants still remain undiagnosed and untreated, and those who receive treatment reveal the benefits of individual case presentation without the advantage of collaborative randomization for the advancement of medical science. Many questions regarding the natural history and spontaneous resolution will remain unanswered until a double-blind study with a larger sample size is conducted.

Early identification of skull deformities should be undertaken by a variety of health care professionals in contact with this young patient population. Referral to experienced team members is appropriate, and definitive diagnosis is largely the result of clinical evaluation. Specific features and distinctions of synostotic and nonsynostotic cranial deformities are well documented. Clinical diagnosis by experienced medical personnel limits additional and costly diagnostic procedures. Timely referral to therapy and/or orthotic evaluation is beneficial to the infant.

Clinical documentation includes a series of anthropometric measurements of the infant skull. These measures are used to justify the need for treatment as well as support the efficacy of the treatment program (see section on treatment recommendations). Reported outcomes support the use of cranial remolding orthoses for improving cranial proportion and/or symmetry in infants 3 to 18 months old. Greater results are noted in younger infants, and recommendations for completing treatment by age 12 months are based on well-documented cranial growth patterns. Significant and rapid circumferential cranial growth occurs in the first 6 months after birth and drops off significantly after age 12 months. Infants older than 12 months still may benefit from orthotic remolding procedures; however, the length of the orthotic treatment program is increased and results are not as favorable. Graham et al.13 found that early diagnosis was critical and that delay may lead to incomplete or ineffective correction. Reduced correction in older babies likely is due to the increase in skull thickness with each passing month and greater difficulty with compliance because of the infant’s improving dexterity and ability to remove the orthosis.

Current research

A systematic review of the literature reveals much agreement on the need for orthotic treatment of moderate and severe skull deformities.2,6,13,14,32,37 Unfortunately, the medical literature reveals an abundance of case studies, case series, and expert opinion. A critical review of the medical literature by Rekate39 in 1998 noted the following: confusion in terminology and definition; difficulty in determining the incidence of deformational plagiocephaly; contribution of both prenatal and postnatal factors to skull deformities; and three primary treatment options, including observation and repositioning, mechanical intervention, and surgery. A review by Lima27 in 2004 reiterated the lack of consistent terminology and definition. Difficulty in establishing the incidence of skull deformities in young infants remained, although many citations suggested common risk factors and early intervention.27 Of the 22 studies evaluated, most presented comparative or case-control studies; no randomized controlled trials were reported. A review by Bialocerkowski et al.4 in 2005 reported that only 16 articles met inclusion criteria (12 case studies and four comparative studies). Based on these publications, it was not possible to draw conclusions regarding the effectiveness of nontreatment, repositioning, and/or orthotic intervention because of poor methodology and potential bias of the researchers.4 More recent studies by Graham et al.13,14 comparing orthotic management to repositioning for management of deformational plagiocephaly and brachycephaly use larger and more equivalent severity groups. The lack of randomized controlled trials hinders medical advancement and treatment criteria and should be addressed in a collaborative effort by medical professionals involved in the care of these infants (Fig. 40-5).

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree