1.2 Conventional clinical practice

Chapter 1.2a The conventional medicine approach

How disease is defined in conventional medicine

Most medical textbooks will describe a disease according to a system that lists the defining characteristics of the disease within a series of categories. For example, the characteristics of chickenpox could be presented as shown in Box 1.2a-I.

Box 1.2a-I Chickenpox: defining characteristics

| Name: | Primary herpes zoster (chickenpox) |

| Epidemiology: | Universal; 95% of people in metropolitan communities have had infection by adulthood |

| Aetiology/cause: | Herpes zoster virus infection. Droplet spread of vesicle fluid |

| Symptoms and signs: | 13–17 day incubation period followed by sudden onset of fever, mild constitutional malaise and, after 2 days, a widespread vesicular rash with lesions appearing in crops mainly on the trunk. Lesions leave a scab after rupturing in 3–4 days. Symptoms can be more severe in adults. Complications include bacterial infection of lesions, pneumonia and encephalitis. Can manifest later in life as secondary herpes zoster (shingles) |

| Investigations: | Can be diagnosed by clinical features alone. Rising antibodies can be assayed after 3–4 days (blood test) |

| Treatment: | For symptoms only. Treat infected lesions with oral flucloxacillin |

| Prognosis: | Usually mild and self-limiting. Case fatality: 2/100,000 in children; 30/100,000 in adults |

| Prevention: | Live attenuated vaccine available for susceptible children. Varicella zoster immune globulin can be given within 4 days of exposure to reduce risk of contracting severe disease in the immunocompromised (e.g. patients with leukaemia or AIDS) |

| Differential diagnosis: | No other illnesses present in this way, but other infectious diseases such as measles, rubella and scarlet fever may be considered in the differential diagnosis |

This model is often termed ‘reductionist’, because of the way in which the body is seen as a collection of smaller parts, and the characteristics of disease reduced down to tangible facts. The reductionist aspects of modern medicine are explored in more detail in Section 1.3.

How disease is diagnosed

To summarise, the three steps to reaching a diagnosis are:

• questioning to elicit symptoms

• physical examination to elicit signs

• performing tests (‘investigations’) and obtaining the results.

These stages will be familiar to anyone who has trained in complementary medicine. However, in most forms of complementary medicine, the emphasis is very much on the symptoms (which are the patient’s own subjective experience), and there is far less emphasis on performing tests. Nevertheless, many practitioners of complementary medicine will make use of objective tests, such as blood pressure assessment, peak-flow assessment, x-ray imaging and analysis of the urine, to give more information about the patient’s condition.

Examination for signs

The case scenario presented in Box 1.2a-II illustrates these first two stages of the diagnostic process (see Q 1.2a-4) .

.

Box 1.2a-II Case scenario

• endocrine causes such as diabetes

• urinary causes such as chronic renal failure

• degenerative disease such as benign enlargement of the prostate gland

• malignant causes such as prostate cancer

• social causes such as drinking too much alcohol or caffeine late at night

Ian’s doctor uses questioning and examination to find out more about the nocturia. In response to her questions, Ian tells her that he has had the problem for some months, when it started with having to get up just once in the night. Now he gets up three or more times, but more often than not just passes a few dribbles of water, even though he has to wait at the toilet for some time. Otherwise he is well, so there are no accompanying symptoms. He finds that to cut down on all fluids in the evening improves the chances of a less disturbed night.

A medical textbook might systematically define BPH as follows:

| Name: | Benign prostatic hypertrophy (BPH) |

| Aetiology/cause: | Degenerative (ageing) disease of unknown cause |

| Incidence: | In most men over 60 years of age |

| Symptoms: | Nocturia, difficulty in urination, dribbling, poor stream |

| Signs: | Smooth enlarged prostate gland felt on rectal examination |

| Investigations: | Test urine for infection (culture), blood test for kidney problems and assessment of prostate-specific antigen to exclude cancer. Detailed imaging of the kidneys and bladder (x-ray and ultrasound) to exclude the kidney problems that can result from prolonged BPH |

| Treatment: | Drug treatment if mild, surgical resection of the prostate gland if severe |

| Differential diagnosis: | Prostatic cancer |

Performing tests

The diagnostic aspect of tests can be best illustrated by continuing with the case scenario given in Box 1.2a-II, as described in Box 1.2a-III. This case history illustrates the process of diagnosis and choice of treatment. Many doctors find this process a pleasing one to follow. The diagnosis is made by a logical process of elimination, and the treatment for a clear diagnosis is usually obvious from the current textbooks or guidelines.

Measurability in medicine

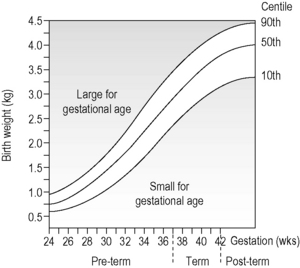

An example of this is shown in Figure 1.2a-I, which illustrates how the birthweight of babies varies according to the week of pregnancy in which they were born. The graph shows three almost parallel curves. The central curve (labelled 50th centile) indicates the average or mean birthweight at any length of gestation. For example, an average baby born at the normal time (the 40th week of gestation) will have a birthweight of about 3.5 kg. The two outer curves (labelled 90th and 10th centiles) are an indication of the range of birthweights of most babies (80% to be precise) born at a particular time. For example, at 40 weeks of gestation, 90% of babies will have a birthweight less than 4.0 kg, and only 10% will have a birthweight less than 2.75 kg.

Figure 1.2a-I • Graph illustrating mean birthweight according to stage of pregnancy at delivery

• The mean birthweight is indicated by the 50th centile line.

(From Lissauer and Clayden 1997, p. 78, with permission).

• some healthy people will, as a consequence of chance, fall outside the normal range

• unhealthy people can fall within the normal range

• if the population from which the normal range is derived is unhealthy, what can be said about normality and how it equates to health?

The issue of the definition of ‘normality’ is relevant when a seemingly well patient undergoes a health check. In a typical health check the patient undergoes a physical examination and some routine tests of bodily functions. Health checks involving a large number of tests are promoted particularly within the private health sector. Such tests raise problems. Does a ‘pass’ on all the tests included in the check really confirm ‘health’? It is well recognised that a person who feels very unwell, for example someone with recurrent migraine, may fall within the normal range for all the tested variables. The doctor might give such a person a clean bill of health on the basis of a health check. The problem here is that what is being measured is not necessarily related to any disease that the person may be experiencing.

To return to the scenario of Ian, the 63-year-old man with nocturia (see Box 1.2a-II), although he may feel that he has been given the ‘all clear’ from cancer, Ian’s doctor cannot totally be sure that the smooth prostate is not hiding a small cancer, and that the PSA result is not a false-negative. Given Ian’s age, together with the signs and test result, cancer would seem unlikely, but remains possible. The doctor has a dilemma whether or not to discuss this small possibility with Ian. It would actually be a very difficult discussion, because most textbooks do not offer information on the certainty of symptoms, signs and test results as predictors of disease. Without undertaking some in-depth research of the literature, the doctor would not be able to put any figure on the probability of an undiagnosed cancer in Ian’s case. Therefore, most doctors choose not to worry the patient about a serious, but unlikely, outcome.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

.

. .

. .

.