Chapter 35 Congenital and acquired disorders

Pediatrics is distinguished by the fact that the child is constantly growing and developing. Growth is an increase in physical measurements. Development is the acquisition and refinement of skills that follow a constant sequence, although at a rate that shows a wide range of normal variation.67

Goals of treatment interventions for children should include maximizing function, facilitating the attainment of specific skills, and encouraging the development of emotional maturity and self-reliance.3 Unfortunately, even though orthoses are commonly included in these treatment interventions, little or no evidence-based literature actually documents the effectiveness of these devices in many conditions.

Congenital foot deformities

Metatarsus adductus

In MA, the forefoot is adducted with respect to the hindfoot. The cosmetic appearance of the foot has been described as kidney or bean shaped. Most often the anatomical site of deformity is the tarsometatarsal joints, with lesser degrees of adduction through the transtarsal joints. The medial cuneiform–first metatarsal articulation often is oblique, and autopsy findings reported by Reiman and Werner80 noted alterations in the size and shape of the first cuneiform. Usually no significant bowing of the metatarsals themselves is seen.

The subtalar joint, and therefore the heel, may be in various degrees of varus or valgus but most frequently is near neutral. Some authors use heel position to make a distinction between typical MA and metatarsus varus.77,97 If the heel is resistant in valgus, the condition may be skewfoot (see section on skewfoot). Significant or rigid heel varus raises the possibility that the deformity is a clubfoot. A key differential between MA and clubfoot is ankle motion. In clubfoot, the calcaneus is resistant in equinus and the foot as a unit cannot be passively dorsiflexed normally at the ankle. The hindfoot in MA can be manipulated through a full range of dorsiflexion and plantarflexion at the ankle joint.

The exact etiology of MA is unknown, but the condition usually is attributed to intrauterine positioning. Although the incidence has been reported as 1:1,000, most practitioners argue that MA is much more frequent.107 Bilateral involvement is present in over 50% of cases, and a positive family history is found in 10% to 15% of patients.77 An initial report of association with hip dysplasia50 has not been reproduced in other studies.62

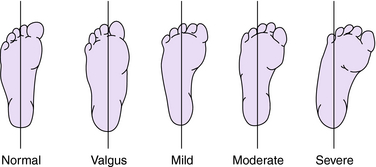

The severity of MA is variable in terms of degree of deformity and flexibility of the foot. Radiographic classification of severity12 has been criticized because of significant variability.23 If a permanent image is desired, an impression of the weight-bearing foot can be made by having the child stand on a photocopying machine.92 A clinical classification system proposed by Bleck14 uses the heel bisector to describe the appearance (Fig. 35-1) and flexibility (Table 35-1) found at physical examination. Another simple assessment of flexibility24 suggests that a type 1 foot actively corrects with stroking or tickling the lateral foot, a type 2 foot corrects only with passive stretching, and a type 3 foot cannot be passively corrected.

Table 35-1 Clinical classification system for metatarsus adductus

| Type | Presentation |

|---|---|

| I | Flexible, with abduction beyond the midline of the heel bisector |

| II | Partly flexible, with abduction only to the midline |

| III | Inflexible, rigid with no abduction possible |

A long-term study by Farsetti et al.36 confirmed that classification based on flexibility at the time of diagnosis is valid. Feet with mild or moderate deformity that were passively correctable did well untreated. Those with rigid MA responded well to correctly performed serial manipulation and plaster casting. These authors advise treatment as soon as the deformity is diagnosed and found not to be passively correctable. Bleck’s large study of MA also emphasized that patient age at initiation of treatment was the best predictor of good outcome.14

For infants and toddlers, treatment of the more rigid MA usually begins with serial manipulation and casting. Long leg casts are most often recommended,77 with the knee flexed, the forefoot abducted, and the foot somewhat externally rotated. Katz et al.56 believe that below-knee casts are just as effective. Casts are changed at 2-week intervals or more frequently, and with each cast change an attempt is made to manipulate the foot into an overcorrected position. Goals include correction of the static deformity and improvement of midfoot flexibility.

In one popular method, the foot is braced with specially constructed shoes, commonly referred to as orthopedic or corrective shoes. The last, in this case meaning the basic shape of the sole of the shoe, determines the type of forces that are directed to the foot. Reverse last shoes (Fig. 35-2), also known as tarsal pronator shoes, turn outward at the midfoot to maintain the abducted position achieved by either surgical or manipulative correction. Straight last shoes accomplish that same goal to a lesser degree. Another useful commercial product is the Bebax shoe (Fig. 35-3),4 which is designed with an adjustable multidirectional hinge between the hindfoot and forefoot sections. This setup allows progressive adjustment of position as the deformity becomes more flexible. Several authors have advised against joining the shoes with the Denis-Browne bar for treatment of MA. Addition of the bar results in a tendency to produce correction through the subtalar joint, leading to heel valgus and flatfoot.12,77

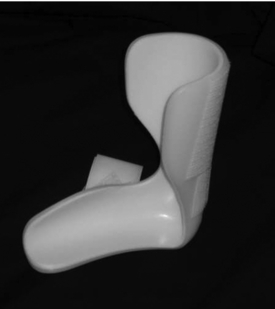

The Wheaton brace (Fig. 35-4), a plastic knee–ankle–foot orthosis (KAFO) or ankle–foot orthosis (AFO) with an extended medial sidewall to prevent forefoot adduction, is frequently used. This polypropylene KAFO/AFO is manufactured with an outward flare shape to the foot section, much like the shape of a reverse last shoe.

Long-term studies of MA in adulthood are scarce. Farsetti et al.36 reported few adult complaints. Most pediatric orthopedists continue to observe the flexible deformities and treat the more severe rigid feet with serial casting, followed by bracing in straight last or reverse last shoes.

Skewfoot

Skewfoot is an uncommon deformity, and it is especially uncommon in the newborn.68,72 The etiology is unknown. The deformity presents generally as MA with heel valgus. On closer inspection, an almost “corkscrew” alignment of the foot is seen. The forefoot is in adduction with some degree of supination, while the hindfoot is in abduction with significant valgus. A key finding is lateral displacement of the navicular on the talus. Unfortunately the navicular does not ossify before age 3 to 6 years, so this displacement is radiographically silent in the infant or toddler. Berg12 described simple and complex types of skewfoot, based on whether or not the calcaneocuboid joint was similarly displaced.

Treatment ranges from serial casting to surgical correction. Although Berg12 believes that milder forms of skewfoot can be corrected with serial casting, Peterson,72 in a review of the world literature, reported that all authors found nonoperative treatment to be unsuccessful. It has been suggested that a skewfoot results from improper manipulation and casting of MA.77 Virtually all of the shoe modifications and orthoses used for treatment of simple MA have the potential to worsen heel valgus. No specific corrective orthosis is available for skewfoot. A foot orthosis (FO) can be custom molded to accommodate the foot shape for pain relief.

Clubfoot

The incidence of clubfoot is different among geographic and ethnic groups, ranging from 0.64 to 6.8 per 1,000 live births.7 About 70% of clubfoot occurs in males, and the right foot is more frequently affected. The condition is bilateral in about 50% of cases.

The etiology remains unknown in most instances. Familial associations are observed, but the genetic relationships are not determined. Clubfoot is quite common in some conditions, such as spina bifida, diastrophic dwarfism, arthrogryposis, and amniotic band syndrome. Clubfoot associated with these syndromes tends to be resistant to both nonoperative and surgical treatment.

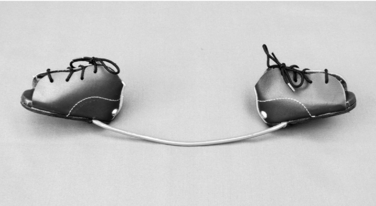

Denis Browne20 described his special splint for treatment of clubfoot in 1934. Treatment consisted of taping the feet onto a bar to maintain the position obtained by manipulation. Modern commercial Denis-Browne bars have adjustable footplates with screw attachments designed to match threaded plugs in the soles of certain “corrective” shoes (Fig. 35-5). The Fillauer bar is a variation on this theme, with adjustable metal clamps designed to grasp the sole of the patient’s shoe (Fig. 35-6). Typically the devices are adjusted to keep the feet externally rotated, augmenting the forefoot abduction forces provided by the shoes and adding an external rotation stretching force at the ankles. The bar can frequently be bent, center downward and away from the patient, to include a valgus moment at the hindfoot. With the footplates strongly rotated externally, this downward central bend adds some ankle dorsiflexion. In contrast to the caution given in the section on MA, application of corrective forces through the subtalar and ankle joints is desirable in patients with clubfoot. The length of the bar should approximate the width of the child’s pelvis. A cost-effective variation of this combined shoes-and-bar orthosis, constructed of basic and readily available materials, has been designed for use in underserved and financially less able regions (Fig. 35-7).

Enthusiasm for comprehensive surgical release and realignment of the clubfoot has waned with the reviews of surgically treated patients published in the 1990s and more recently noted disappointing outcomes.5,29,55 The majority of current treatments emphasize nonoperative techniques, with limited operative interventions reserved for resistant or recurrent deformity. These techniques aim to provide painless foot function through the life of the patient with less regard to cosmesis or radiographic parameters. The French method of comprehensive physical therapy and taping and the Ponseti method of serial manipulations and holding casts both seem effective for restoration of a flexible plantigrade foot in most cases.

The initial stage of the French method relies on daily manipulation of the clubfoot by trained physiotherapists.11,81 Between therapy sessions, foot position is generally maintained by taping. In this sense, the “orthosis” consists solely of the tape. The first English-language description of this program suggested using a Denis-Browne splint between therapy sessions for the first 2 or 3 weeks,11 but subsequent reports presented in detail the technique for application of nonelastic and elastic tape and discouraged rigid bracing. In the early 1990s, continuous passive motion, provided with a specially designed machine appropriate to infants, was incorporated into the French method. At about the third month, when the foot is reasonably well corrected, continuous passive motion is discontinued and the family assumes responsibility for continuing the physical therapy and taping. When the child reaches an appropriate age to cooperate, active therapy exercises are added. No special shoes or molded orthoses are recommended. Treatment ends at about age 3 years, with monitoring to completion of growth.

In contrast, the Ponseti regimen75 emphasizes the use of maintenance orthoses. This method of clubfoot treatment begins with serial manipulations and application of holding casts. The manipulations must be performed in a specific way, initially maintaining the forefoot in supination to facilitate correction of the cavus component of the deformity. The forefoot is abducted in supination, with counterpressure over the dorsolateral head of the talus. The calcaneus must not be grasped or pushed so that movement of the calcaneus through the subtalar joint is not restricted. Rather, repositioning of the calcaneus occurs simultaneously and spontaneously as the talonavicular joint is reduced. Satisfactory overcorrection of the cavus, adductus, and varus usually is accomplished between cast numbers three and six, at which time residual ankle equinus is assessed. A percutaneous heel cord release is frequently done at this stage, followed by another 3 weeks of cast immobilization. Maintenance of correction requires strict adherence to a bracing program. Ponseti advises using an abduction orthosis consisting of straight last shoes attached to the Denis-Browne bar, with the footplates set at 70 degrees out-toe, and with the bar bent to encourage hindfoot valgus and about 15 degrees of ankle dorsiflexion. This appliance is worn on a full-time basis for 3 months, or until the child is learning to crawl. Night bracing is continued to age 3 or 4 years. Ponseti strongly states that an AFO is not effective for maintaining correction.76 Although few outcome studies are available, published long-term results of the Ponseti method seem encouraging. More specifically addressing the use of orthoses, several authors have observed a very high recurrence rate in patients whose families did not adhere to the bracing recommendations.31,99

Congenital vertical talus

The etiology of CVT is unknown. Candidate genes have been suggested for some families.28,89 Associations have been made with chromosomal disorders100,101 such as trisomy 13, 14, 15, and 18 as well as neuromuscular disorders such as spina bifida, arthrogryposis, and sacral agenesis.

Radiographic confirmation of this diagnosis requires a lateral view of the foot in maximum plantarflexion.61 The navicular will not be ossified in the infant, so direct visualization of the talonavicular relationship is not possible. However, in true CVT a line drawn through the long axis of the talus will project plantarward to the ossific nucleus of the cuboid.

Treatment of CVT begins with passive manipulation and holding casts, which stretch the soft tissues. Traditionally, actual realignment of the bones by closed means was not expected. This deformity almost always was thought to require surgical correction. A casting regimen pioneered by Dobbs et al.30 advises gradual reduction of the talonavicular joint by manipulations suggestive of a “reverse Ponseti” method. This regimen minimizes surgery, requiring only pin fixation of the talonavicular articulation with percutaneous heel cord release.

Calcaneovalgus foot

This positional variation is a frequent finding among newborns and must be differentiated from CVT. The incidence of calcaneovalgus probably is much greater than the reported 1:1,000 live births,106,108 as it ordinarily resolves spontaneously and therefore may never attract medical attention. It is common in the firstborn of young mothers and is thought to be the result of intrauterine packing. No inheritance patterns are known.

Kite60 pointed out the association of external rotation contractures of the hips with calcaneovalgus foot. Wetzenstein106 noted the association with flexible flatfoot in later life. Congenital posteromedial bowing of the tibia is sometimes associated. It initially can cause some diagnostic confusion because a normal foot can have the cosmetic appearance of calcaneovalgus when significant posteromedial bowing is present.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree