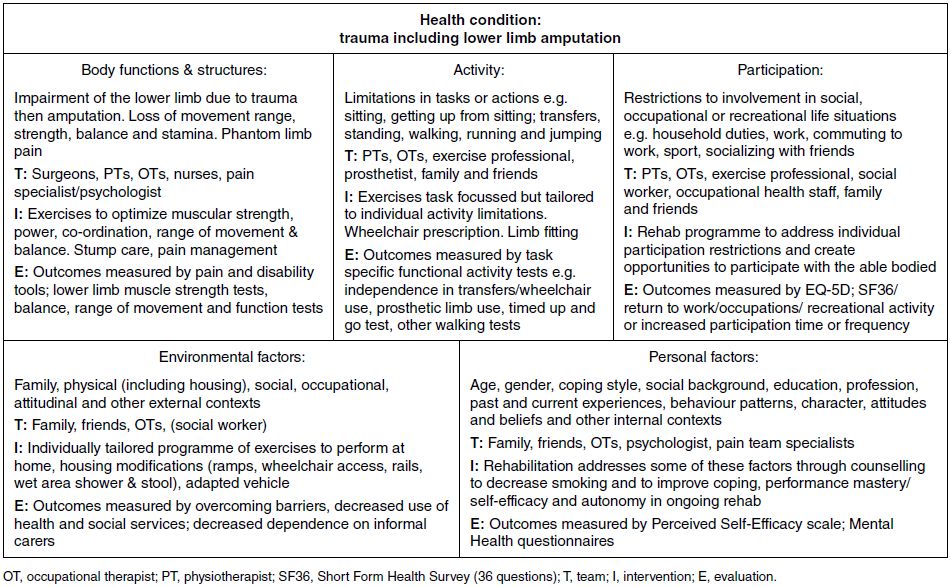

Table 7.1 Using International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) terminology as a mapping tool for interprofessional rehabilitation. Case study one: Simon, involved in a road traffic accident resulting in lower limb amputation.

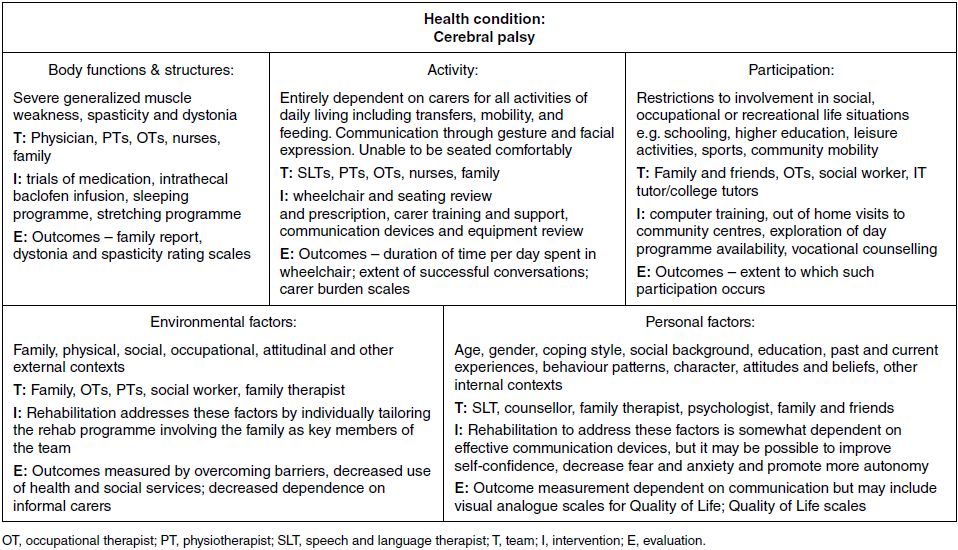

Table 7.2 Using International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) terminology as a mapping tool for interprofessional rehabilitation. Case study two: Angela, a young adult with cerebral palsy.

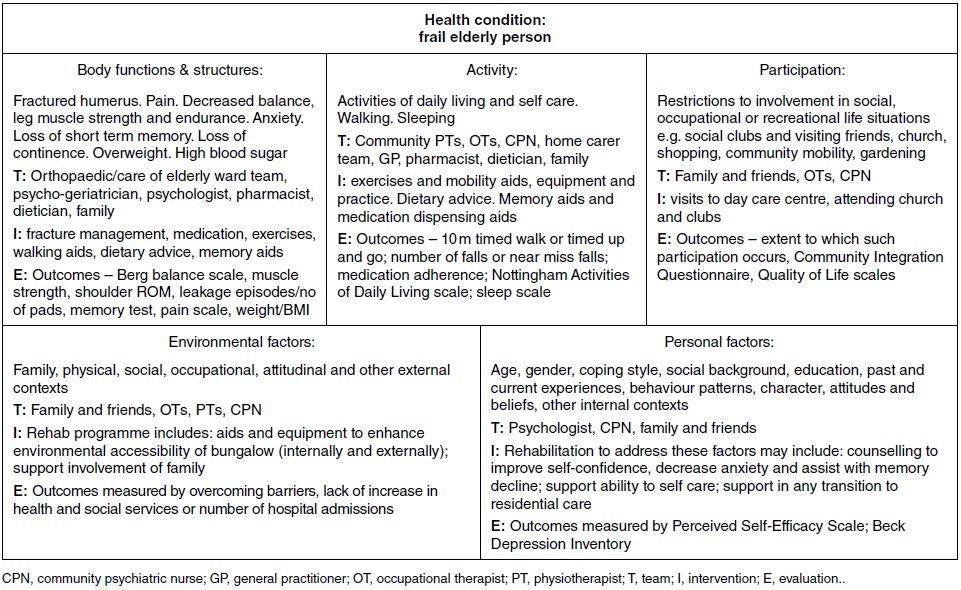

For all three cases their situations have been documented in accordance with the ICF framework as depicted in Tables 7.1, 7.2 and 7.3. For such complex cases we propose that this mapping approach is a useful exercise for a rehabilitation team to employ, at least as a starting point for working interprofessionally. It ensures everyone has a shared understanding about what the rehabilitation process is aiming to achieve for Angela, Mary or Simon as well as a common language to aid communication across the team. Clearly the map operates at one particular time point and so would need updating at appropriate intervals, particularly for Angela as she gets older and her condition alters or for Mary as her living circumstances change and her health deteriorates.

Table 7.3 Using International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) terminology as a mapping tool for interprofessional rehabilitation. Case study three: Mary, an older adult with complex needs.

7.8 Revisiting the definition of rehabilitation

In considering the primary task of rehabilitation, this book has focused mainly on the idea that our domain of interest is ‘functioning’. The key target of rehabilitation interventions is taken to be some aspect of ‘functioning’ (as described by the ICF). However, another very interesting concept that may have strong parallels with rehabilitation practice is ‘capability’ and ‘freedom’. Siegert and colleagues have argued that restoration of human rights to people with disabilities following injury or illness can be seen as one of the objectives of rehabilitation (Siegert and Ward, 2010; Siegert et al., 2010). Using a model of human rights that has the values of ‘freedom’ and ‘well-being’ at their core these authors discuss how rehabilitation is able to restore rights that may have been lost or diminished as a result of ill-health. In a sense, human rights can be seen as a key outcome of successful rehabilitation.

There is another way to consider human rights in the context of disability. Article 27 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights states that ‘Everyone has the right freely to participate in the cultural life of the community, to enjoy the arts and to share in scientific advancement and its benefits’ (United Nations, 2011). Among other human rights articulated by the Declaration, this strongly suggests that participation in ordinary community life is a fundamental human right and that exclusion is a breach of those rights. If we consider disability to be located within societal failure to accommodate to people with impairment, rather than located within individuals with impairment (the social model of disability versus the biomedical model of disability), and define disability as restrictions in community participation of differently abled people, due to barriers imposed by the way society conducts itself, then it follows that disability is actually synonymous with a breach in the human right to full community participation. This certainly does not imply that we have a right to perfect health. Disability and health can be related but are clearly not the same thing. What is implied though, is that society needs to make much more effort to minimize disability, not just to accord people with disabilities the same human rights as everyone else. This does not mean just considering environmental barriers, but includes access to rehabilitation services and technologies that aim to improve people’s autonomy and participation in their communities. When rehabilitation is defined as a process that aims to accomplish these kinds of outcomes, rather than being concerned with improving impairments, then it follows that there is also a ‘right to rehabilitation’.

Freedom is a concept that is clearly not limited to rehabilitation practice. Amartya Sen, the Nobel prize winning economist, has written about freedom as a key requirement and driver for economic development (Sen, 1979, 2000). But there are many parallels with his writing about freedom and what we have described in this book as good rehabilitation practice:

- success of society is measured by freedom of its members versus success of rehabilitation measured by the ability of the client to do what he/she wishes;

- health is only ‘good’ to the extent it allows freedoms versus better functioning is only ‘good’ to the extent it achieves the client’s goals;

- freedom is both the ‘ends and the means’ versus participation as learning is as important as learning to participate.

Having made the point that disability and health are quite different things there have been recent moves to redefine health so that it better reflects the emphasis on living with chronic conditions and maximizing capacity to participate in life, given that these ongoing conditions have to be managed rather than cured (Huber et al., 2011). These authors propose that health should be defined as ‘the ability to adapt and to self-manage’ within the context of having capacity to manage a complex set of circumstances (Huber et al., 2011). The problem with this proposed change in definition is that there may still be the tendency to divide people into ‘healthy’ or ‘un-healthy’ categories. In reality we all have varying degrees of ‘healthiness’ or ‘un-healthiness’, or as we have already mentioned we are all disabled (or differently ‘abled’), some more so than others. So although we support the need for a discussion about possible redefinitions of health we are more intrigued by how ‘adaption’ and ‘self-management’ can be defined and measured. Huber and colleagues (2011) indicate that some assessment of well-being or happiness will be needed to judge the success of a person’s adaptation or self-management. In the rehabilitation setting we would emphasize the importance of partnership, between service user and provider, and that self-management arises from ‘productive partnerships’ that are likely to result in better health outcomes (Verkaaik et al., 2010).

The definitions we gave of rehabilitation at the start of this book did go some way to show how we are already thinking and practising with some of these concepts in mind. Thus, rehabilitation is not necessarily about returning someone to their pre-injury or pre-illness state, rather it is about helping the person to maximize their functioning within a given health condition, including a condition that may be deteriorating over time (like the case study of Angela in the preceding section). We can therefore now go on to consider some areas of healthcare where we might extend the model of rehabilitation practice.

One area of healthcare that has already been doing this is in the domain of palliative and end of life care. For example, there is an increasing awareness that rehabilitation and palliative care can learn from each other and that patients might benefit from a seamless interface between these two disciplines. Cancer treatments are now so advanced that many people with cancer are living with the illness rather than dying from it. At the same time many people with degenerative neurological conditions eventually require palliative care either at home or in a hospice or hospital. This means that patients requiring rehabilitation will often also require palliative care and sometimes both. The two fields both deal mostly with chronic and/or incurable conditions and share a focus on enhancing quality of life rather than curing a condition. Consequently, there is much for professionals to learn and potential benefits for patients and their families through increasing communication and even integration of these two disciplines (Turner-Stokes et al., 2008).

The ageing population adds further to the need for managing chronic and complex conditions. Rehabilitation professionals with limited resources have also to rethink their traditional approaches of delivering therapeutic treatments to patients and instead will need to work on ways to help patients self-manage their conditions, in much the same way as a mentor might do for helping someone in their personal development.

Finally, advances in biomedicine continue to obviate some of the needs for ongoing treatment. For example, developments in the speciality of regenerative medicine include things such as implants of stem cells that have the potential to grow into functional neurones or joint cartilage cells. These exciting developments do not mean rehabilitation is redundant; rather that rehabilitation practice will change as patients require guidance about how to train their new neurones or look after their new joint cartilages.

7.9 Limitations related to the scope of this textbook

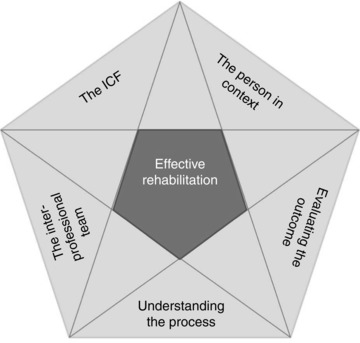

Although we have covered a number of topics in this textbook we are not claiming this is a comprehensive guide to all rehabilitation practice. Instead, we have focused on five core themes and also recommend to interested readers that they explore further some of the ideas presented and make use of the recommended additional resources listed at the end of each chapter. For example, we suggest there is still much to be learnt from broadening our knowledge about contextual factors such as ethnic and cultural perspectives. Further examination of cultural awareness or sensitivity and cultural safety will also be helpful (Bhopal, 2006; Polaschek, 1998; Reid et al., 2000).

Other debates related to rehabilitation practice are also important. For example William Levack (personal communication, 2011) has highlighted the concern that rehabilitation planning can cause conflict within teams and distress for individual personnel (Mukherjee et al., 2009). Levack proposes that a deeper understanding of general ethical principles (e.g. Blackmer, 2000) and how they could be applied to rehabilitation planning and practice might be useful for addressing these concerns. Levack notes that many of the ethical dilemmas facing rehabilitation professionals do not relate to life and death situations (unlike much of medical ethics) so it is necessary for a more sophisticated consideration of ethics in rehabilitation practice to be developed (Levack, personal communication, 2011). For further reading on this topic see Levack (2009), Siegert and Ward (2010) and Siegert et al. (2010).

In addition we have not debated some specific areas of practice, such as the transitional care between children’s services and adult services for people with disabling conditions acquired in childhood. This is becoming increasingly important as more children with severe and complex conditions survive into adulthood.

Finally, although we have briefly mentioned advances in biomedical technology as having an impact on rehabilitation practice, we have not given extensive coverage to this topic, nor to the implications arising from developments in telemedicine, internet service provision or global healthcare initiatives.

7.10 Future directions of interprofessional rehabilitation

Throughout this book we have provided examples of how research evidence informs rehabilitation practice but we specifically want to highlight here some developments in the research agenda that are likely to have a substantial impact on rehabilitation research. The first is the publication by the Medical Research Council of Great Britain of a framework for developing and evaluating complex interventions (Medical Research Council, 2008).

The Medical Research Council complex interventions framework provides opportunity for unpacking the ‘black box’ of rehabilitation intervention (DeJong et al., 2004). To produce the strongest evidence for the effectiveness of a treatment the recommended approach is to carry out a definitive clinical trial. For a new drug this means a double-blinded, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Clearly this is methodologically challenging to do for many rehabilitation interventions. For example, in the context of interventions that require active engagement (e.g. exercises) on the part of the patient, it is seldom possible to blind the therapist who is providing the rehabilitation intervention and nearly always impossible to blind the patient about which intervention they are receiving. The Medical Research Council framework allows for a more pragmatic approach to trial design yet at the same time ensuring the research is carried out in as robust a manner as is possible. This is achieved by recommending an iterative process involving four stages: development (including feasibility and pilot work), evaluation (the clinical trial), dissemination, and sustainability (including implementation or return to the development stage for the next iteration to occur). Key recommendations are for the embedding of process evaluation during the work, the use of qualitative research approaches to capture the experiences of people participating in the research (patients, carers and providers), and the active involvement of patients, carers and the public in all stages of the research. These recommendations can result in detailed work to document or ‘map’ the intervention (see for example Abraham and Michie, 2008) to create a protocol that can be used to cross-check whether or not health professionals are delivering the intervention with fidelity to the original treatment programme.

In the example of an exercise programme the intervention map might include details of the precise techniques a therapist uses to teach strengthening exercises to a patient. The details provided are likely to include the choice of exercises, the muscle action required, the order of exercises, the number of repetitions and sets, the rest periods between sets, exercises and repetitions, the resistance used (intensity), the repetition speed and the weekly training frequency (Hoffman et al., 2005). An intervention map, like this one for an exercise programme, can then also be used to help assess whether or not the patients are adhering to the intervention. The map might also include details about the strategies used for motivating the patient to do their exercise as well as provide details about the mode of delivery (e.g. group exercise classes or an individually tailored home programme). Planning a process evaluation also ensures data are collected on recruitment rates, attrition rates and loss to follow-up as well as whether the intervention or the research process was acceptable or not. The qualitative work complements this and helps to uncover the experiences of participants and providers thereby providing further information about why the intervention did or did not work (as opposed to the trial, which only answers the question ‘does it work?’).

The Medical Research Council framework strongly recommends the involvement of service users in the development and process evaluation work. We have already introduced the concept of patient and public involvement in research as a way of demonstrating the importance of including the patient as part of a rehabilitation team (Chapter 3) and of putting the patient in the centre of rehabilitation practice (Chapter 6). Although the benefits of patient and public involvement (PPI) are yet to be fully evaluated a review has been undertaken about the impact of PPI within applied health research. The review reported that PPI helped to increase recruitment to projects, was of particular value within clinical trials and qualitative research, and was found to benefit both research participants as well as those taking part in the PPI process (INVOLVE, 2009).

As the most recent Medical Research Council framework was only updated in 2008 it is still a relatively new approach to designing clinical trials and the development work phase for interventions such as complex rehabilitation programmes can take years. So the lead-in time to the definitive trial can be quite long and a full-effectiveness and cost-effectiveness trial can take several years to complete, especially if long-term follow-up is required. Thus, the results of such research endeavours will be forthcoming sometime in the future, creating an exciting possibility that such work will help to expand the evidence base for rehabilitation practice.

A further impact of research upon rehabilitation practice that is yet to be fully appreciated is the paradigm shift concerning brain recovery processes following acquired brain injury such as stroke or trauma. A paradigm shift (see Kuhn, 1962) occurs when an accepted way of thinking is completely overtaken by new knowledge, a classic example of such a shift occurred when people realized that the Earth was not at the centre of the universe but was just another planet revolving around the Sun (see Siegert et al., 2005 for discussion of the Copernican revolution in astronomy as one of Thomas Kuhn’s archetypal paradigm shifts). In acquired brain injury the traditional view was that, once damaged, the brain could not recover and there was no new growth of neurones. Instead, improvements in functional ability could only occur through compensation techniques (either other parts of the brain taking over the role of the damaged area or physical strategies involving other body parts that compensated for the lack of function in affected areas). Rehabilitation interventions and practices were orientated around this premise. More recently it has been demonstrated that new growth of brain cells, and the connections between them, can occur. This phenomena is called neuroplasticity (see Robertson, 2000) and this opens up huge possibilities for learning again how to perform functional activities. Indeed, we are all neuroplastic and have the ability to learn new things throughout our lives, albeit at probably a slower pace than when we were children. The implications for rehabilitation interventions and service provision are substantial; stroke survivors should no longer be told that their recovery has reached a ‘plateau’ (and so rehabilitation provision stopped). Instead, we suggest rehabilitation professionals will have to find a way of supporting patients to move on to self-training by learning how to plan, set goals and implement their own rehabilitation programmes. Research has yet to be undertaken that demonstrates such approaches are effective for long-term stroke survivors, but some services in the UK are already beginning to adopt this type of approach in the later stages of rehabilitation for people with acquired brain injury (Balchin, 2011).

In terms of the future of healthcare more generally an interesting development that is likely to have an impact on rehabilitation has arisen from the WHO’s ‘Framework for Action on Interprofessional Education and Collaborative Practice’ (WHO, 2010). This document provides a comprehensive overview of interprofessional working, taking a global perspective and encompassing all health professions and policy makers as well as those allied to education, housing and environment. The WHO framework links interprofessional education (IPED) and communities of collaborative practice (see Chapter 3) as the future for health and education systems. The proposed framework is also regarded as addressing the demographic changes in health and well-being in the context of the increasing prevalence of chronic and complex conditions. Table 7.4 provides a summary of the mechanisms identified in the WHO report that will shape the future of interprofessional education and collaborative practice within healthcare and education systems.

Table 7.4 Summary of identified mechanisms that shape interprofessional education and collaborative practice. (World Health Organization, 2010 reproduced with permission.)

| Interprofessional education | Collaborative practice | Health and education systems |

| Educator mechanisms Champions Institutional support Managerial commitment Shared objectives Staff training Curricular mechanisms Adult learning principles Assessment Compulsory attendance Contextual learning Learning outcomes Logistics and scheduling Programme content | Institutional supports Governance models Personnel policies Shared operating procedures Structured protocols Supportive management practices Working culture Communication strategies Conflict resolution policies Shared decision-making processes Environment Built environment Facilities Space design | Health-services delivery Capital planning Commissioning Financing Funding streams Remuneration models Patient safety Accreditation Professional registration Regulation Risk management |

The WHO’s Framework for Action indicates that there will remain a strong drive for IPED to be embedded in health professional training programmes. The challenges ahead lie in implementing this and in creating the communities of practice that underpin collaborative working. The Framework is not prescriptive as such, instead the report intends to offer ideas to ‘policy-makers with ideas on how to contextualize their existing health system, commit to implementing principles of interprofessional education and collaborative practice, and champion the benefits of interprofessional collaboration’ (WHO, 2010, p. 11). The mechanisms listed in Table 7.4 will help achieve this and are salient to rehabilitation practice regardless of the global scope and context of the original Framework report.

These ideas about the future are just that, they are possibilities rather than an attempt to predict things. However, we do believe that the five core themes presented in this book are unlikely to quickly go out of fashion and will stand you in good stead and help you adapt to the advances and changes that do occur. Nevertheless, the themes are not intended as a new dogma about how interprofessional rehabilitation should be done. Therefore, despite the evolution of professional roles, good practice in rehabilitation is likely to reflect the themes of this book, irrespective of new technologies or changing team structures. By holding on to these core values we believe that good rehabilitation practice will be maintained.

Figure 7.1 The five core themes as a framework for effective rehabilitation practice. ICF, International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health.