2 Senior Lecturer and Professional Lead for Occupational Therapy, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Southampton, United Kingdom

5.1 Introduction

How often have you been asked recently to participate in a research study, a political poll or a customer satisfaction survey? We live in an age that is obsessed with information, counting and measurement. Much of this preoccupation with numbers and facts is due to the invention of the modern, high-speed computer, which makes collecting and analysing information so easy. However, at times it can feel as if we are being assailed by facts and figures, rather than helped by them. We feel swamped with information and ideas but short of time to assimilate all this information and reflect upon its implications. In the clinical environment busy health professionals can sometimes feel besieged by institutional requirements to collect data on their daily activities. At the same time there is constant pressure on health professionals to keep up to date with the growing amount of new information in their field and the implications of all this new knowledge for everyday patient care.

This chapter is about measurement in rehabilitation and how we measure the results or outcomes of the process of rehabilitation. It is also about how we decide which measure or measures are the best to use for our specific purpose and targeted interventions. In particular we consider the best ways to measure the outcomes of interprofessional rehabilitation while keeping the individual client’s or patient’s perspective as the central focus.

An outcome in rehabilitation has been defined as ‘a characteristic or construct that is expected to change owing to the strategy, intervention, or program’ (Finch et al., 2002, p. 11). Another definition states that: ‘Outcome refers to the expected or looked for change in some measure or state. In other words, a patient will enter a rehabilitation program in one state and may change as a result of the intervention. The new state constitutes this outcome’ (Wade, 2003, p. 27).

Finch et al. (2002) suggest that three measurement paradigms with particular relevance to evaluating rehabilitation outcomes are (1) the World Health Organization’s (WHO) International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF), (2) health-related quality of life (HRQoL), and (3) cost. Finch and colleagues note that outcomes can be targeted at the level of the organ, the person or the group, and they argue that the ideal outcome to measure is one that is most affected by our strategy, intervention or programme and minimally affected by other influences. Outcomes need to be measured in some way by clinicians and this just means that a set measurement tool (for example a standardized questionnaire, functional test or goniometer) is used to quantify these observations (Barnes and Ward, 2000).

This chapter will attempt to address a number of specific, important and complex questions about rehabilitation outcome measures. Specifically it will attempt to address the following questions.

- Why do we use outcome measures?

- What are the important outcomes to measure?

- Who decides what to measure?

- What makes a ‘good’ measure?

- How can we best apply outcome measures in clinical practice?

- How should outcome measurement influence practice and service delivery?

Why do we use outcome measures in rehabilitation?

A recent survey of New Zealand physiotherapists treating patients with low back pain, found that the majority of the therapists did not routinely or systematically use standardized outcome measures in their day-to-day clinical practice, preferring instead to rely upon their individual clinical judgement and the patient’s verbal report (Copeland et al., 2008). Interestingly, this finding is not unique with similar results reported in studies from Scotland, Canada and the USA (Chesson et al., 1996; Huijbregts et al., 2002; Jette et al., 2009). Given such findings, one might reasonably ask why already busy rehabilitation clinicians would want to add to their workload by making data collection on outcome measures a routine part of their clinical practice? In fact there are important ethical, clinical, financial and scientific reasons why outcome measures are useful and important for routine practice in rehabilitation settings. But underpinning all these reasons is the prevailing belief that the patient’s voice must be heard and should feature in any consideration of health outcomes. This makes sense, as rehabilitation professionals we treat the individual and not simply the condition.

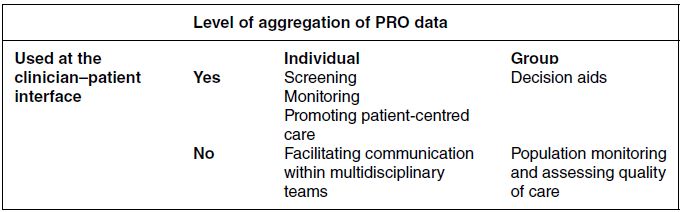

Ultimately how the patient feels they are progressing or coping is paramount. In both the UK and the USA it has been generally accepted that it is important to obtain the patient’s view on therapy outcome and governments have endorsed recommendations to increase the use of patient reported outcome measures in documenting the effectiveness of health services (Marshall et al., 2005; US Department of Health and Human Services Food and Drug Administration, 2009). Increasingly you will see and hear the term ‘patient-reported outcome measures’ (PROMs) to refer to tools designed to collect information on what patients think about their therapy progress, their health status and the quality of service delivery. Greenhalgh (2009) has recently proposed a taxonomy or system for classifying the different applications PROM data can be used for (see Table 5.1, Greenhalgh, 2009). In this taxonomy PROMs are classified according to two dimensions. The first dimension is based upon whether or not a person’s scores on the measure are used at the level of the individual patient–clinician interaction. The second dimension is concerned with whether patient scores on the measure are considered as individual or grouped data.

Table 5.1 Taxonomy of applications of patient-reported outcome (PRO) in clinical practice. (From Greenhalgh, 2009. Reproduced with kind permission from Springer Science + Business Media.)

Greenhalgh observes that individual PROM data can be used in the clinician–patient interaction for (1) screening, (2) monitoring, and (3) promoting patient-centred care. Screening involves using a standardized PROM, with all patients in a service, as a diagnostic aid for detecting problems in individuals that are frequently not diagnosed. For example, depression is common in neurological rehabilitation and the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) is a popular screening tool (Siegert et al., 2009, 2010). If a patient scores above a certain cut-off point on the BDI there is a high probability of a mood disorder and further investigation is warranted. Monitoring refers to the ongoing observation and measurement of specific aspects of a patient’s condition or life circumstances to see if things are improving, deteriorating or remain about the same. For example, the Palliative care Outcome Scale (POS) is a brief, 10-item questionnaire that monitors important aspects of a patient’s comfort, clinical care and psychological/spiritual well-being in palliative care settings (Hearn & Higginson, 1999; Siegert et al., 2010).

Promoting patient-centred care means that a measure is used to foster patient self-management of their health and to encourage patients to become active partners in the long-term management of their health. This is particularly important in rehabilitation where people must be actively engaged in the process for it to be at all effective. PROMs can assist this process by helping to ensure that patients participate in determining the important goals for their own treatment. For example, the WHOQOL-BREF is a self-report measure that asks people about physical, psychological, social and environmental dimensions of their overall quality of life (QoL). It can be used to monitor changes in QoL in the management of chronic health conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis (Taylor et al., 2004).

Greenhalgh’s (2009) taxonomy also includes those situations in which individual PROM data is used without a patient–clinician interaction occurring. An example is when individual PROM scores are used to facilitate communication about patients within a multidisciplinary team. For example, an inpatient team on a specialized neurorehabilitation ward might use a measure such as the Functional Independence Measure + Functional Assessment Measure – UK version (UK FIM+FAM) at fortnightly team meetings to consider the progress of each patient (Turner-Stokes et al., 1999). The FIM+FAM serves as both a focus for discussion and a shared framework for all disciplines to co-ordinate their diverse skills and knowledge in assisting each individual patient toward greater independence. It has two subscales that measure physical and cognitive disability/independence and can highlight the specific targets for rehabilitation necessary to achieve greater independence before discharge from an inpatient service. It can also serve to remind the team when an individual patient is not making the progress expected and so indicate when some concerted clinical problem solving is required.

Two other uses for PROMs data that emerged from this typology involved the use of grouped, rather than individual, data. Grouped data refers to when patients are studied as part of an audit, research project or service evaluation and offers generalized indications about how groups of individuals respond to a certain intervention. Such information can help clinicians review the effectiveness of interventions and help guide decisions about service planning – such as deciding which interventions are most effective for which patients. This is particularly relevant when results from randomized controlled trials are used to help individual patients and their clinicians make decisions concerning their own treatment or clinical management. For example, patients considering undergoing cancer treatments that have unpleasant side-effects can be informed about patient data on QoL from trials of these treatments.

The second use of grouped PROM data is for ‘evaluating the effectiveness of routine care and assessing the quality of care’ (Greenhalgh, 2009, p. 118). For example the Services Obstacles Scale (SOS) is a brief (six item) questionnaire that was developed to provide information on the barriers to rehabilitation services in the community that people with a traumatic brain injury have experienced (Kolakowsky-Hayner et al., 2000; Marwitz and Kreutzer, 1996).

Implicit in the above discussion of PROMs is the notion that using them will necessarily improve the quality of the service and care provided. In other words it is assumed that the collection of PROM data will somehow change clinician behaviour and spur people into action to improve the delivery of care. But is there any evidence to support this? The best current evidence available does not allow a simple yes or no answer to this question. Two recent reviews observed that there was good evidence that feedback from PROMs often has positive effects such as improving diagnosis (especially in mental health settings) and improving clinician–patient communication – but it remains to be established whether regular use of PROMs has a substantial impact on the health of most patients (Skinner and Turner-Stokes, 2006; Valderas et al., 2008; Greenhalgh, 2009).

What are the important outcomes to measure?

As society progresses, definitions of health and well-being also evolve – reflecting current knowledge and expectations as well as changing political, economic and social influences. Outcome measures have developed from being rather narrow, biomedical indicators of outcome, such as statistics on death, disease and disability, to include much broader instruments that attempt to capture the individual’s personal and subjective experience of disability, health and well-being. There has been a continuing evolution of healthcare definitions and the language used to capture ability and function. Today the focus on recording outcomes is much more on people’s abilities and their role in society rather than just on their symptoms and limitations.

In deciding what are the important outcomes to measure in rehabilitation there are two key issues that we need to consider from the outset. The first issue is precisely which level of functioning is most appropriate or relevant to assess in measuring outcome. This is important because it makes sense to measure outcomes at the level at which our therapy or intervention is targeted. In rehabilitation we are fortunate to have a sophisticated conceptual framework developed by the WHO that enables us to categorize and compartmentalize most elements of a person’s daily function – the ICF (WHO, 2001). The second issue here concerns who decides what the important outcomes to measure are in the first place? Is it the patient, the family, the clinician, the service manager, the funder or government? This question of ‘important to whom?’ is arguably the single most important issue in outcome measurement. However, to answer this important question, it is helpful to first understand where the ICF fits in to outcome measurement and how outcome measures relate to the ICF model.

ICF level of functioning and outcome measurement

Derick Wade has argued persuasively that the WHO model of health, disability and functioning provides an excellent conceptual framework for clinicians to match up their interventions with appropriate outcome measures (Wade, 1991). The WHO model has been developed and refined further since Wade’s influential text on measurement in neurological rehabilitation was first published and the current version is presented earlier (see Chapter 2, Figure 2.1). The important point about the ICF in relation to outcome measures is that it requires a clinician to specify at which level (body functions and structures, activities, participation, environmental and personal factors) they intend to intervene and to measure their effectiveness at that level. So if we intervene at the level of body structures and functions, such as muscle strengthening in physiotherapy, then clearly we need an outcome measure that operates at this level. In contrast, if we use social skills training to increase vocational involvement in people recovering from severe traumatic brain injury (TBI), then we need to measure outcome at the participation level.

But rehabilitation is a complex intervention and typically involves multiple professionals working with a patient and their family/carers over several months and sometimes years. Moreover an intervention can be highly specific, such as a single session of occupational therapy focused on dressing oneself, or it can be comprehensive, such as a community-based programme supporting the families of people with a TBI. Wade suggests that it is nevertheless important to be specific and ‘refer to the outcome of a specified intervention measured in a specific way, reflecting the interests of specific groups/stakeholders…’ (Wade, 2003, p. 27).

In other words before we dare to inflict a new outcome measure on our clients, patients or colleagues we should always be able to specify the following features of our outcome measurement plan:

- the intervention that we are interested in evaluating;

- the level of function, in ICF terms, where this intervention is believed to have an impact;

- the proposed outcome measure that captures change at this level of function;

- and who identified this outcome as the important one?

In practice this will often demand that we measure outcomes at more than one ICF level or domain. A good example of this comes from the progress that has been made in upper limb surgery for tetraplegia since the early 1980s. There is substantial evidence from case series that forearm tendon transfer surgery can produce improved fine arm–hand functioning in people with tetraplegia and that these gains are maintained over time (Rothwell et al., 2003). However, most of the outcome research on this surgery has focused exclusively on direct improvements in hand function such as hook grip and pinch grip values. These are measurements at the level of body structures and functions and research has focused on this level because it is here that hand surgeons have been able to directly evaluate their success. However, recent approaches to evaluating the success of this type of hand surgery have focused more on how the surgery has affected the person at the participation level (Sinnott et al., 2009). For example, the following quote is from a person who had the surgery a few years ago: ‘I think the surgery has helped my level of confidence. For example when I go out in public I can be sure of managing a cup of coffee and eating with a fork. These things help with self-esteem. It also means I can do more for myself and other people…’ (Sinnott et al., 2004, p. 398).

This kind of outcome information is important for people who might be weighing up whether or not to have the surgery but also for administrators who might be considering how many operations to fund each year. The point here is that we often need to evaluate outcomes at different levels and the ICF provides a useful conceptual framework for doing this. This example also illustrates the point that different outcomes matter more or less for different stakeholders. Similarly, there are many outcome measures that could be considered for the following case study and possible outcome measure options using the WHO model of health, disability and functioning framework are considered here.

QoL in rehabilitation

One important concept in modern health sciences that does not feature prominently in the ICF is the construct of QoL (Fayers and Machin, 2007; Leplege and Hunt, 1997). The ICF is largely concerned with function or what a person can do whereas QoL is more concerned with overall how happy or satisfied a person feels about their life at this point in time. The concept of function is relatively objective – we can observe if a person can walk, talk, get dressed, drive a car or earn a living. In contrast the notion of QoL is entirely subjective – only the individual can say how happy they are with their current lot in life. QoL is notoriously difficult to define or rather it is difficult to find a definition that everyone can agree on. Calman asserted that QoL must take into account numerous aspects of a person’s life and that only the individual can report on their own QoL. Calman argued for a model in which QoL is conceptualized as the difference between a person’s hopes and expectations and their present lived experience (Calman, 1984). The WHO defines QoL as ‘individuals’ perception of their position in life in the context of the culture and value systems in which they live and in relation to their goals, expectations, standards and concerns’ (Division of Mental Health and Prevention of Substance Abuse, 1997, p. 1). The WHO definition is the basis of the WHOQOL measure and posits six important dimensions or domains of QoL – physical health, psychological, level of independence, social relationships, environment and spirituality/religion/personal beliefs. However, because it is so difficult to adequately define QoL most workers in the field prefer to use the more limited term Health Related Quality of Life (HRQOL) (Fayers and Machin, 2007). HRQoL measures can be divided into generic and disease-specific HRQoL measures. One example of a generic HRQoL measure is the Short Form-36 (SF-36) that has been used to gauge QoL in a broad range of health conditions as well as in healthy people (Quality Metric, n.d.). In contrast the QOLIE-89 was specifically developed to measure QoL in people with epilepsy (Devinsky et al., 1995). The strength of a disease-specific instrument is that the items are developed with input from people with the condition concerned, resulting in a set of items with direct relevance to people with that condition. The strength of more generic instruments is that they can be used to compare QoL across people with different conditions.

Who decides which outcomes are the important ones?

We already know that patients’ and health professionals’ perspectives of disease and functional ability often differ (Nothnagl et al., 2005; Salaffi et al., 2005) so relying solely on clinician-rated measures gives only a limited view of rehabilitation outcome. If we accept that health is a subjective concept, dependent upon physical, cognitive and emotional factors, and affected by social, economic and geographic influences, then it is clear how important it is to obtain a patient’s perspective on their own state of health and progress in rehabilitation.

A recent qualitative study that looked at the views of patients towards two widely used back pain outcome measures concluded that both of these measures were inadequate from a patient perspective. The measures were criticized for not fully capturing the personal experiences of living and working with back pain and for not addressing all of the most relevant changes that can occur with this condition (Hush et al., 2010). The study also criticized these measures in relation to the time frame for assessment and the functional domains covered. It would be premature and unwise to discard two well-established measures on the basis of a single study that included only 36 participants from one country, but the study does illustrate some important trends in rehabilitation outcomes.

However, to get a better picture and understanding of the impact of a condition we need to consider using PROMS and, using the example of our earlier case about Jackie, there would be a number available to us. These could be either generic or site and/or disease specific.

When deciding which outcome measures to use it would be useful to consider how a tool was developed and who was included in the construction and testing of the tool. The development of an outcome measure should ideally include groups of patients and clinical specialists to decide which are the most relevant and pertinent questions to ask and how the outcome should be framed. Patients need to be asked what matters most to them and what issues are the most important that need to be addressed in a measure. A sound outcome measure will have been developed using committees of experts in the field that include patients (and or family/carers), clinicians and academics. Ensuring that patients are consulted at all stages in the development and refinement of outcome measures is essential.

It may also be necessary for outcome measures to be updated at regular intervals so that items or questions do not become out of date and to ensure that they accurately reflect contemporary lifestyles and values. One example of this is the work conducted by Stamm and colleagues exploring the usefulness of standardized questionnaires used to assess people with hand-based osteoarthritis (Stamm et al., 2009). This team explored whether the concepts important to patients with hand osteoarthritis (OA) were covered by the most commonly used outcome measures. Only a third of the concepts identified by patients with hand OA as important were covered by those standardized questionnaires in common use. None of these questionnaires considered how having hand OA had psychological consequences, the different qualities of pain, aesthetic changes or impact on leisure activities – all of which were identified as important by this patient group. In addition the outcome measures were seen to be out-dated by the patients. For example, some important activities such as using a mobile phone and caring for grandchildren, were not represented in these outcome measures, which had been developed several years ago.

What makes a good outcome measure?

Once we have decided what the important things to measure are then we need to decide how

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree