Assessment templates and established procedures for collecting this information can be very helpful to ensure that a consistent approach is taken for all people entering into a rehabilitation service and that no important aspects of the assessment are omitted by mistake. When rehabilitation is provided by an interprofessional team, it can be beneficial if one member of the team (a senior nurse, allied health professional or doctor) conducts an interdisciplinary team assessment (see also Chapter 3). This assessment would include collection of all the basic health and contextual information that is needed by the entire team. Such an approach reduces duplication (avoiding several team members spending time collecting the same information on multiple occasions) and improves team communication.

The exact content of an interdisciplinary team assessment will of course differ depending on the type of rehabilitation service being provided. Different types of services (e.g. paediatric services, community-based mental health services, outpatient pain clinics, inpatient rehabilitation services for spinal cord injury etc.) all require different types of information. However, regardless of the clinical context, it can be useful to structure much of the interdisciplinary team assessment around the framework provided by the ICF (WHO, 2001). Table 4.1 provides an example of how components of the assessment process can be mapped onto the ICF framework (see Chapter 2 for more information about the ICF and its application to clinical rehabilitation).

The information arising from the patient’s assessment is used in a number of ways. It informs the team about the potential causes of disability and areas where further gains are needed in order for the patient to make progress in their functional abilities and social participation. It provides a basis for predicting the likelihood of success of different types of interventions and the possible range of outcomes that could reasonably be expected for the patient. The assessment process also identifies areas where a patient is at risk of further harm (such as arising from pressure areas, urinary tract infections or falls) so that preventive strategies can be implemented to reduce the chances of these events occurring. Finally, discussion of the assessment with the patient and their family, in conjunction with discussion of their values, hopes, expectations, and understanding of their situation, can dramatically inform the goal-setting process, which is central to good rehabilitation planning.

Organizing the interdisciplinary team to undertake their assessment can sometimes be usefully incorporated into the role of a keyworker (or case manager), whereby one member of the team becomes the central point for contact and communication between the patient, their family and the interprofessional rehabilitation team (see also Chapter 3). In addition to the interdisciplinary team assessment, the keyworker can also meet regularly with the patient and their family to explain the rehabilitation process, set and revise goals, discuss the patient’s progress and present the team’s perspectives on the likely outcomes from further clinical intervention. The keyworker can also invest time to find out more about the patient and family’s expectations for interventions and recovery, about any concerns they might have about the patient’s health and well-being or services received, and can report this information back to the rest of the rehabilitation team. Furthermore, the keyworker can take responsibility for the overall coordination of the rehabilitation process for that individual, directing the rehabilitation planning for the team and ensuring that it is carried out in a timely fashion. In some teams, the keyworker is the one who chairs the team meetings or family meetings when that particular patient is discussed (see Chapter 3 for more about team meetings).

Table 4.1 Matching assessment components to the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) (WHO, 2001).

| ICF component | Examples of assessment components |

| Health condition Body structures and functions | Diagnosis (or diagnoses) Arousal Physiological function (e.g. blood pressure, heart rate, respiratory rate, blood tests, urinalysis) Pain Muscle strength Range of movement Neurological symptoms (e.g. reflexes, spasticity) Sensory function (e.g. sensation, vision, hearing) Nutritional status Eating or swallowing difficulties Skin integrity and wounds Cognition (e.g. memory, orientation, awareness, concentration, perception) Communication Continence Sexual function |

| Activity limitations | Mobility Self-cares (bathing, grooming, toileting, dressing/undressing) Risk of falls Managing finances Driving |

| Participation | Social roles in the home Social roles in the community Work or training status |

| Environmental factors | Residential situation Work environment Disability support services being received Medications Assistive technology used Respiratory support used Family/friend involvement Family/friend attitudes and beliefs Legal status (e.g. power of attorney) |

| Personal factors | Age Gender Ethnicity Religion Vocational identity Self-identity Personal attitudes and beliefs |

4.3 Goal planning

Early in the rehabilitation process, goals should be set to direct the course of rehabilitation interventions (or at the very least, to make explicit the intended outcome of the rehabilitation service for the individual patient). Some have presented goal planning as a relatively simple, straightforward way of interacting with patients in order to prioritize interventions, facilitate teamwork and improve health outcomes (Wilson, 2008). However, increasingly it has become apparent that multiple approaches to goal planning exist (see Table 4.2), involving a variety of procedures and serving a range of different, sometimes conflicting functions (Levack et al., 2006a, 2006b; Playford et al., 2000). In this section an overview of common approaches to goal planning for rehabilitation has been provided. This overview is intended as a guideline only. Rehabilitation teams and individual health professionals are advised to tailor their approach to goal planning for the specific needs of their patients and the objectives of their services, drawing on relevant goal theory and research wherever possible.

Table 4.2 A list of approaches to goal setting.

| Approach to goal setting | References |

| Goal attainment scaling | Original version: Kiresuk and Sherman (1968) Contemporary approaches: Turner-Stokes (2009); Turner-Stokes and Williams (2010) |

| Goal setting based on the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure | Pendleton and Schultz-Krohn (2005); Phipps and Richardson (2007); Trombly et al. (2002); Wressle et al. (2002) |

| ‘SMART’ goal planning | Barnes and Ward (2000); Mastos et al. (2007); McLellan (1997); Monaghan et al. (2005); Schut and Stam (1994); Bovend’Eerdt et al. (2009) |

| ‘RUMBA’ goal planning | Barnett (1999) |

| Self-identified goal assessment | Melville et al. (2002) |

| Goal management training | Levine et al. (2000) |

| The Rivermead Life Goals Questionnaire and approaches to goal planning from Rivermead Rehabilitation Centre | McGrath and Davis (1992); McGrath et al. (1995); Wade (1999a & b) |

| Approaches to goal planning from the Wolfson Neurorehabilitation Centre | McMillan and Sparkes (1999) |

| Contractually organized goal setting | Powell et al. (2002) |

| Collaborative goal technology | Clarke et al. (2006) |

| Goal setting as part of the Progressive Goal Attainment Programme | Sullivan et al. (2006) |

| Patient-centred functional goal planning | Randall and McEwen (2000) |

| Goal setting based on the Patient Goal Priority Questionnaire or Patient Goal Priority List | Åsenlöf and Silijebäck (2009) |

RUMBA, Relevant, Understandable, Measurable, Behavioural and Achievable; SMART, Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, and Time-limited (but see text for alternative definitions).

What is a rehabilitation goal?

All human behaviour is arguably goal directed and, in its broadest sense, the term ‘goal’ can include a wide range of concepts – from biological goals (e.g. to change one’s body temperature or reproduce) to complex, cognitive or aesthetic goals (such as to live a moral life or achieve a career objective); from goals that relate to a moment in time and goals that relate to a lifespan (Austin and Vancouver, 1996). In the context of rehabilitation however, the term ‘goal’ is generally used to mean something much more specific; more explicitly linked to clinical work. Rehabilitation goals are usually characterized by the following:

- reference to a desired future state that the patient cannot currently achieve;

- having the patient as the subject of the goal (e.g. ‘that John will have no episodes of incontinence of urine over a 48-hour period within 2 weeks’ as opposed to ‘That the nurses will take John to the toilet every 4 hours’ – the latter being an example of an ‘action plan’ or ‘intervention’);

- an emphasis on achievement at the level of activity and participation rather than body function and structure (e.g. ‘that John will transfer independently from his bed to his wheelchair within 2 weeks’ as opposed to ‘that John will lift his leg against gravity with the knee straight while in supine lying within 2 weeks’);

- an emphasis on outcomes to be achieved as a result of clinical interventions or the patient’s effort, rather than as a result of the passage of time or natural healing and recovery;

- being explicit rather than implicit (i.e. explicit goals being those goals that the clinical staff and, usually, the patient and other involved people, such as their family, are consciously aware of; as opposed to implicit goals that have not been consciously expressed).

Regarding this last point, the act of reaching for a cup is a motor activity with an implicit goal (i.e. to take the cup). Asking a patient to reach for a cup (versus just asking them to reach into mid-air) is an example of using implicit goals to influence behaviour (Trombly and Wu, 1999) as the goal of taking a cup changes the kinematics of a reaching motion. However, using such activities as a clinical intervention (e.g. for exercise therapy after a stroke) is not an example of ‘goal setting’ in rehabilitation in its usual sense. Therefore while these types of ‘task goals’ are goals in the psychological sense, they are not examples of ‘rehabilitation goals’ as such. To make ‘independently using a cup to drink’ the subject of a ‘rehabilitation goal’, clinicians would have to explicitly set this as a goal, using some form of clinical documentation and only after discussion and negotiation of this as a goal of therapy with the patient.

Of course, exceptions to all of these general rules do exist. For instance, patients who have impairments related to orientation, memory or communication may not be explicitly aware of goals that their clinicians and family are working on or may only have limited capacity to participate in goal selection. Goals related to body function and structure (e.g. range of movement, muscle strength, respiratory status) may sometimes be useful to set in certain contexts – particularly in the early days of recovery from a very severe injury or illness, when goals related to activity or social participation may not be as meaningful. Some clinicians and their patients may also feel that it is valuable from the context of family-centred practice to set goals featuring family members as the subject of the goal (Levack et al., 2009), although others have argued that only patients should be the subject of goals, and never the significant other people in their lives (McMillan and Sparkes, 1999; Randall and McEwen, 2000).

Due to all these possible variations in context and opinion it is difficult to come up with a universal definition of a ‘rehabilitation goal’ that suits all clinical work. Wade (1998), however, writing for an interprofessional audience, offered one alternative, defining a ‘goal’ as: ‘A future state that is desired and/or expected. The state might refer to relative changes or to an absolute achievement. It might refer to matters affecting the patient, the patient’s environment, the family or any other party. It is a generic term with no implications about time frame or level’ (Wade, 1998, p. 273).

The key point here, however, is that although it is arguable that all human behaviour is goal directed, and that rehabilitation cannot therefore occur without having goals of some kind, it is not true that all goals are ‘rehabilitation goals’ in the sense usually intended by rehabilitation teams. Rehabilitation goals are actively selected, intentionally created, have a purpose and ideally are shared by the people participating in the activities and interventions designed to address the consequences of acquired disability.

What is ‘goal setting’ and ‘goal planning’?

In clinical rehabilitation, Wade (1998) has suggested that the terms ‘goal setting’ and ‘goal planning’ can be considered synonymous, defining them as: ‘The process of agreeing on goals, this agreement usually being between the patient and all other interested parties’ (Wade, 1998, p. 273). Similarly, Playford et al. (2000) have suggested that goal setting is: ‘The process of agreeing on a desirable and achievable future state’. Nevertheless, in rehabilitation both goal setting and goal planning usually refer to a relationship between an individual patient and an individual or group of health professionals plus any other involved individuals such as family members. Goal setting should involve some degree of communication about the hopes, expectations, and intentions of all people involved in a single episode of rehabilitation, and a negotiation of the direction in which rehabilitation should head.

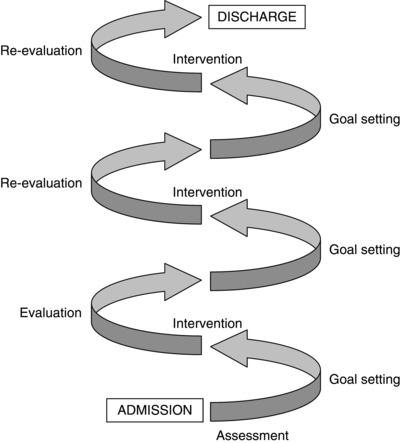

Application of goal planning to rehabilitation

As shown in Table 4.2, multiple approaches to goal setting in rehabilitation exist. These approaches can differ in terms of a number of factors such as the professional group (or groups) intended to use the approach, the intended patient population for the approach, the process by which goals are selected or negotiated, the recommended characteristics of the actual goals set (e.g. whether or not they should be measureable, activity related, realistic or ambitious and so on), the intended reason for having goals for rehabilitation or participating in goal setting, and the way the goals are subsequently used in the clinical environments. However, there are a few features that are common to many standard approaches to goal setting in rehabilitation, typically involving the following:

- finding out about the perspectives of the patient (and family) regarding their expected and/or desired outcomes from rehabilitation;

- finding out from the patient (and family) information about the context of their life outside of rehabilitation including their personal values, priorities, strengths, roles, relationships, and usual living environments (considering both physical and social factors);

- communicating information to the patient (and family) regarding clinical perspectives on the causes of their impairments and activity limitations, clinical factors influencing their prognosis for recovery, and the likely effectiveness of rehabilitation options;

- identifying long-term goals with patients and their family;

- identifying short-term (and sometimes medium-term) goals with patients and their family;

- identification of the actions (or ‘tasks’) required to achieve the goals, and the assignment of roles and responsibilities to the various people involved in undertaking these actions;

- specification of time frames for achievement or re-evaluation of goals;

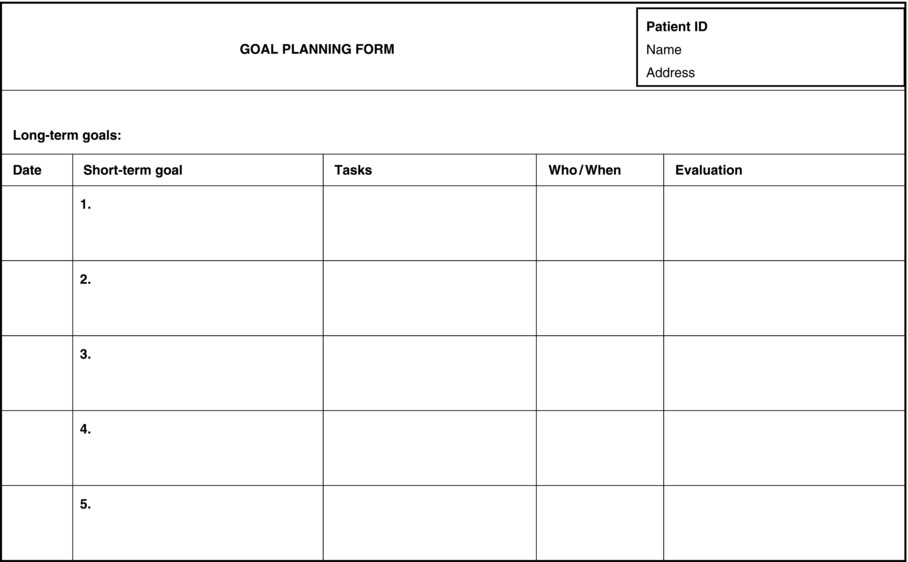

- documentation of all long-term goals, medium-term goals, short-term goals, tasks, assigned responsibilities and time frames using a standardized template. (See Figure 4.3 for an example of a basic template.)

These activities can be carried out as part of a formal meeting with the patient, their family and relevant members of the clinical team. If a formal meeting is planned then the patient, their family and clinical staff should all be adequately prepared for this meeting (see also Chapter 3). Preparation of the patient and their family should involve providing education about the rehabilitation process and the role of goal setting within it, giving them sufficient time to consider what they would like to raise for discussion at the meeting.

Consideration ought to be given to when the initial goal-planning meeting is best held with patients and their families. If formal goal planning is delayed for too long, decisions about clinical interventions may have already been made and therapies implemented before goals are even set, making the whole goal-planning process far less relevant. If goal planning is undertaken too quickly however, insufficient time may have been spent on building a rapport with the patient and their family, learning about their priorities and usual social context, before goals are set. There are no firm rules about when is best to set initial goals for rehabilitation, but one guideline might be that the longer and more complex the anticipated rehabilitation programme, the more time should be spent on building a working relationship with the patient and their family before confirming the goals of rehabilitation. In these types of service, pushing patients to set goals for therapy within their first interactions with clinicians, before they have had time to consider the implication of their newly acquired disability, may well be premature and result in superficial, tokenistic goals, rather than goals that reflect their personal context and world view.

Setting long-term goals

Prior to setting short-term goals and assigning clinical tasks, it is usually a good idea to establish the patient’s long-term goals. In rehabilitation the phrase ‘long-term goal’ is sometimes used just to refer to any goal that is to be achieved at a more distant point in time (e.g. after discharge from a service or after a set period such as 4 or more weeks), with ‘short-term goals’ being the ‘steps’ required to make progress towards this ‘long-term goal’ (e.g. to be achieved after periods of 2 weeks or less). However, ‘long-terms goals’ can often be qualitatively different from ‘short-term goals’ as well. For example the phrase ‘long-term goals’ can at times be used to refer to: (1) goals that emphasize the direction the patient wishes to take with their life, (2) goals that are stated by the patient without reinterpretation or negotiation by the rehabilitation team, or (3) goals that are grouped under the ICF category of ‘participation’.

Long-term goals can be identified by simply asking patients questions such as ‘where do you see yourself in 6 months’ time?’ or ‘what do you hope to eventually achieve from rehabilitation?’ If this open-ended approach is unsuccessful then prompts under headings such as ‘family’, ‘work’, ‘leisure’, ‘community activities’, ‘social relationships’ and ‘friends’ may provide the starting points for discussion about these goals. In some situations (for example if the client has cognitive problems) this discussion will benefit from input from members of their family.

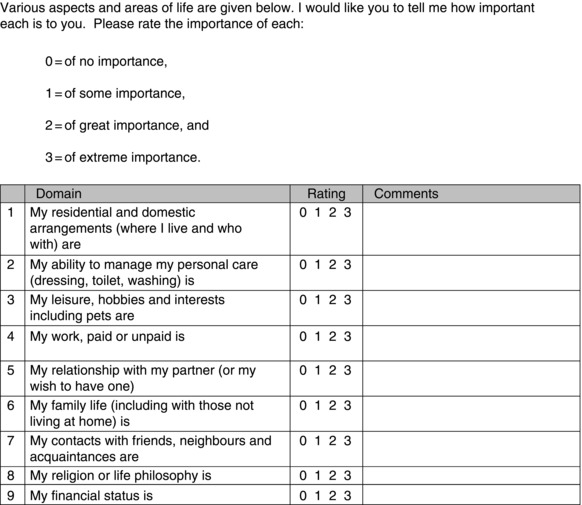

Alternatively, long-term goals can be established by using some method for identifying a patient’s life goals. Life goals have been defined as ‘the desired states that people seek to obtain, maintain or avoid’ (Nair, 2003). Although a number of tools are available to evaluate life goals (Conrad et al., 2010; Nair, 2003), there is one tool designed specifically for the purpose of facilitating meaningful goal planning in rehabilitation settings and this is the Rivermead Life Goals Questionnaire (RLGQ). A copy of this questionnaire has been reproduced in Figure 4.4.

One important point regarding the RLGQ is that although ‘scores’ can be generated from its items, it has in no way been promoted as an outcome measure. This is because it is impossible to say whether changes in scores on individual RLGQ items represent improvements or deterioration in health outcomes. Also of note, apart from the original development work that went into the RLGQ (McGrath and Adams, 1999), which suggested that RLGQ scores had adequate test–retest reliability, very little other research has been conducted on the psychometric properties of this assessment tool or to develop it further.

Figure 4.4 Rivermead Life Goals Questionnaire. (Courtesy of Rivermead Rehabilitation Centre, Abingdon Road, Oxford, UK.)

Nevertheless, scores resulting from application of the RLGQ can be useful and, at times, surprising: patients might indicate that they have no interest whatsoever in managing their personal cares but rather would like to focus more on abilities that could return them most quickly to leisure activities that they previously enjoyed; people who otherwise appear to be in a stable, long-term relationships might indicate that in fact the strength of their personal relationships with a spouse matters to them very little at all. Thus, the RLGQ helps clinicians (who are otherwise, frankly, strangers in their patients’ lives) avoid making assumptions about individual patients based on superficial appearances, clinical experiences or on the clinician’s own values and priorities. The RLGQ can also be a very useful tool for ‘breaking the ice’ with patients, facilitating a way into discussion of things other than the patient’s immediate health problems when goal setting.

Setting short-term goals

Short-term goals are generally set by the rehabilitation team in negotiation with the patient. Short-term goals may start as objectives for rehabilitation identified by patients or may be simply recommended by a health professional as a necessary step towards achieving the patient’s long-term goal. Regardless, short-term goals are usually converted into some type of standardized format according to the rehabilitation team’s preferences, usually to make the goal more objective or to fit within what the clinicians believe they can provide. Most short-term goals are set at the ICF level of ‘activity’. For example, goals focusing on a patient’s ability to walk to the bus stop, manage basic financial transactions and tolerate light physical activity might be the subject of short-terms goals leading on to a long-term goal of returning to work.

Time frames are universally recommended for short-term goals, indicating a point at which the achievement, non-achievement or progress towards the goal is to be evaluated. In an interprofessional context, individual health professionals may have more or less responsibility than their colleagues to help patients achieve some specific short-term goals – although most goals are usually intended as ‘team’ goals, the achievement of which is part of the overall rehabilitation plan. Common approaches to standardizing short-term goals include use of the ‘SMART’ acronym, Randall and McEwen’s (2000) ‘who, what, how well, by when’ method, and Goal Attainment Scaling (GAS).

‘SMART’ goals

One commonly promoted approach to standardization of short-term goals is the use of the ‘SMART’ acronym. To confuse matters, however, there is no single, agreed interpretation regarding what this acronym stands for (Wade, 2009). Schut and Stam (1994), in the earliest health science publication to mention SMART goals, stated that the SMART acronym referred to goals that were Specific, Motivating, Attainable, Rational and Timed (Schut and Stam, 1994). Alternatively, McLellan (1997) used this acronym to emphasize that goals should be Specific, Measurable, Activity-related, Realistic and Time-specific, whereas Barnes and Ward (2000) preferred Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant and Time-limited. Other version of the SMART acronym also exist (Marsland and Bowman, 2010; Mastos et al., 2007; Monaghan et al., 2005; Wilson, 2008).

Rubin (2002) suggested that the SMART approach to goal planning originated as a way to quickly communicate decades of research from industrial organizational psychology, but that over time, as people attempted to fit SMART goals into different contexts, the acronym drifted away from its original meaning and from the research on which it was based. This may explain in part the differences in the recommended qualities of goals resulting from the SMART approach: these various interpretations may be based more on clinical opinion rather than high-quality research. For instance, from a research perspective there is no consistent evidence that goals that are ‘realistic’ or ‘achievable’ result in better health outcomes for rehabilitation patients than goals that are highly ambitious or difficult to achieve (Levack et al., 2006c). In fact, research from the field of industrial organizational psychology has suggested that challenging short-term goals, which might be difficult to achieve, tend to result in higher levels of performance on work tasks than goals that are easily achievable (Locke and Latham, 2002).

Randall and McEwen’s ‘who, what, how well, by when’ method

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree