The professionals in the team described in Mrs Greenwood’s case were still operating within their traditional roles but had agreed some joint and underpinning approaches to the various interventions required by Mrs Greenwood, so they were going some way towards working interprofessionally. Generally however, the prefix ‘inter’ (as in interprofessional or interdisciplinary) suggests more potential overlap in roles, with boundaries being blurred or relaxed. This might be a consequence of a team having been together for some time, secure in their professional skills and knowledge, but having a more sophisticated understanding of team members’ strengths, preferences and styles. As an example, the second author of this chapter, Claire, joined a relatively new community learning disability team in which interventions were initially offered according to professional demarcation (so the physiotherapist and speech and language therapist jointly offered a communications and exercise class). As the team matured and became more confident and trusting, creative solutions to client-oriented problems evolved that were less reflective of professional domains. Latterly the team chartered a canal boat for clients, this provided respite care for families but also a variety of opportunities for learning through practice (see Chapter 6 for more about this). The clients practised food preparation skills, the trip facilitated community engagement through stopping at public houses along the canal waterways for an evening drink and provided clients with the opportunity to learn about a new leisure activity. Canal locks, getting on and off of the boat, and standing on the deck and in the interior offered strength, transfer and balance challenges, and steering the canal boat provided a popular opportunity to be in control and empowered. This move to an interprofessional framework can signify a more holistic way of working, characterized by sharing and knowledge transfer between team members. This facilitates effective teamwork and enables the team to create its own momentum and ethos, resulting in a whole that is greater than the sum of its parts, a point that we will return to later in this chapter.

Another relatively new approach to rehabilitation teamwork is ‘transdisciplinary’ practice. King et al. (2005) describe transdisciplinary rehabilitation teams as promoting cross-treatment with the service user centrally involved, sharing responsibilities and a blurring of roles. Advantages include valuing of information transfer, lack of any specific role dominance and expansion of professional expertise, resulting in more effective provision. One of the key mechanisms for promoting transdisciplinary working is joint training or education. Browner and Bessire (2004) provide an example of how this was achieved, through the contribution of senior staff from all rehabilitation professions, within the context of the development of basic competency education modules for staff working with brain and spinal cord injured people. The modules were delivered to 95 of the 110 staff members working within a rehabilitation facility over a 4-day ‘Competency Fair’. Positive outcomes included greater appreciation of each others’ roles, empowerment to share roles, greater crossover of duties, a better understanding of transdisciplinary care, improvements in patient care and increase in knowledge. Just as we mentioned in the example given in the section about interdisciplinary approaches, the move to a transdisciplinary culture may take some time. Various authors have investigated what might be needed for this development to occur, and King et al. discuss Walker and Avant’s (1995) five premises that are likely to be required before it is possible to apply this approach to rehabilitation: (1) role extension; (2) role enrichments; (3) role expansion; (4) role release, and (5) role support (King et al., 2005). We have used the example of working with patients, who have chronic low back pain and are attending a chronic pain clinic, to suggest ways in which these conditions might be achieved in rehabilitation (see Table 3.1). In addition, an effective transdisciplinary team can be characterized by stability of staff (i.e. low turnover) and an underpinning philosophy of co-operation and collaboration as opposed to individual (professional) achievement.

The different terms that are frequently encountered when describing the overall structure of a rehabilitation team reveal how some subtle differences in terminology can have the potential to influence how well a team might work. We go on to discuss some of the characteristics that enable a team to work well together, and some of the common problems that can occur within teams.

3.3 Characteristics of good teamwork

Perhaps one of the first introductions to the notion of teamwork to which we are exposed as children is during school physical education. Some will have had experience of playing for the year or school team – perhaps rounders, football or netball. Sporting teams have their own distinct roles and rules, but in considering the characteristics of a good rehabilitation team, reflection on successful sports team can prove illuminating. Similarly within commerce, successful businesses are often the product of a close cohesive team, sharing similar aspirations, loyalties and ethos. So as trainee health professionals, we tend to be reasonably familiar with the idea of teams.

Teams that work well and teams that work less well

When reflecting on flourishing teams, there is often a tendency to attribute success to personal characteristics of team members, such as a strong leader, loyal members and individuals with creativity or confidence. However, the organisational and environmental context within which a team operates, although receiving less attention, is as important as any individual traits in facilitating effective performance. These contextual factors are recognized within theory about team performance and these contextual factors are also important for influencing how performance can be maintained over time. Drinka and Clark (2000) for example, identify factors at three different levels that have an impact on healthcare team performance. At the first level are both personal factors (such as communications skills, leadership style and maturity) and professional factors (these include expertise, dedication to an ideal and knowledge of roles of others). At the second level intra-team issues relate to structure, for example formal leadership, norms and physical placement and process issues relate to goal setting, building trust and managing conflict. At the third level organizational issues are both internal, such as team philosophy, resource allocation and rigid or flexible rules, and external issues, for example national policy and funding. We can learn from industrial and organizational psychology literature (for example Guzzo and Shea, 1992) about some established variables upon which effective teamwork relies and apply this to interprofessional rehabilitation.

Table 3.1 Potential facilitators for transdisciplinary working in a chronic pain team: examples based on Walker and Avant’s (1995) five premises and King et al.’s (2005) discussion points.

| Premise | Potential facilitators |

| Role extension |

|

| Role enrichments |

|

| Role expansion |

|

| Role release |

|

| Role support |

|

- Task interdependence: the extent to which team members must interact to achieve a goal. In the earlier case study involving Mrs Greenwood this would mean all team members using the principles of ‘consistency and reinforcement’.

- Outcome interdependence: the degree to which responsibility for the outcome and any consequences are shared within the team, regardless of the success or otherwise of these outcomes. In Mrs Greenwood’s case this would mean whether or not she went on to have another fall, or moved into residential care.

- Potency or team self-efficacy: the belief that the team has the necessary skills, attributes and resources to achieve the desired goals. In the example the team needs to be confident that they have effective communication procedures and sufficient resources in order to be consistent in what and how they are asking Mrs Greenwood to undertake rehabilitation activities, and that the same messages are being reinforced.

(Adapted from Guzzo and Shea, 1992)

These authors describe ‘resources’ as ‘environmental supports’, similar to the organizational factors identified by Drinka and Clark (2000), and it is clear that the environmental context can have an impact on team performance. One of the most obvious environmental contextual factors that has an impact on the capacity of a team to reflect on, appraise and evaluate its own performance is time. When time to work with patients is limited there is likely to be a tendency for the team to focus solely on patient needs as perceived at that moment and in the immediate context that person is in. This is likely to lead to task-orientated care and fewer team interactions, with these tasks often mistakenly described as goals (see Chapter 4 for more detail on goals). If we take the example of an older patient who has experienced a fall, the ‘goal’ might be to work towards ‘independent mobility’, an activity which if done safely and successfully might be a regarded as ‘goal’ achieved, but probably only by one professional group (for example, physiotherapists or occupational therapists). However, a closer analysis of the situation reveals that the important goal is really about being able to perform kitchen activities of daily living after they have been discharged home, in particular being able to make a cup of tea. Ward-based physiotherapists and occupational therapists therefore work with the patient to build strength and promote balance, they rehearse kitchen-based activities with support, nurses encourage and reinforce use to increase confidence; family members learn when to help and when to stand back; and community-based therapists check how the home kitchen layout supports or hinders easy completion of key kitchen tasks. Although the original goal identified by the time-pressed team was not wrong, the original goal of ‘independent mobility’ was not a sufficiently detailed analysis, and lacked collaboration of input or involvement of the patient to guide the whole team.

Sometimes when there is limited time the opposite problem will occur, so that instead of the focus being on the individual activities, the team will announce a big ‘goal’, for example, to discharge the patient home. Again this might be an important aim for all concerned and so worthy of pursuit. However, there may only be an implicit understanding of this type of goal as it has not been fully articulated among the team members, and nor is there any consensus about how it is to be achieved and who will be contributing which element. It is also possible that both these events take place within the time-pressed team so an implicit broad goal of discharge home co-exists with the generation of a range of isolated tasks. These tasks may be devoid of context and lack coherence despite the fact that each professional thinks they will be needed.

All this suggests that effective teamwork stems from a balance of understanding and by accurately describing patient circumstances, and carrying out the necessary actions required to address these circumstances. This requires the skill to analyse the often complex needs of the service user and their family in their specific context. Using the example of referral following a fall, issues that require careful assessment will include personal factors, such as coping with disability or loss, confidence, self-efficacy and other psychosocial factors. In addition the assessment may also need to consider the perhaps more obvious physical needs a person has. This will also include environmental factors such as the availability of community resources or residential care, the need for a home environment that is safe and provides cues to activity, maybe through the use of telecare. In occupational therapy one of the most widely used models of practice is the Canadian Model of Occupational Performance (Canadian Association of Occupational Therapists, 1997) and its latest iteration includes the addition of engagement (Townsend and Polatajko 2007). From this model the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (Baptiste et al., 2005) has been developed to guide therapists in their assessment process, so that the person, their ‘occupations’ or activities in relation to self-care, leisure and productivity, and the environment are all taken into account. Although this outcome measure is derived from an occupational therapy model of practice, it has been used within interdisciplinary rehabilitation research to provide a comprehensive evaluation of the effectiveness of a rehabilitation intervention (e.g. Esnouf et al., 2010).

Other contextual factors that can have an impact on the success of interprofessional teams are the systems that are in place and the availability of processes such as assessments, key worker systems and team meetings. Such processes can facilitate the co-ordination and delivery of packages of rehabilitation from a variety of team members who are aiming to address complex needs. For instance, an older patient who has had a hip fracture following a fall wants to go home and a key issue for her is the preservation of her autonomy. In order to support her desire for autonomy (and to help her test out its practicality) the physiotherapist and occupational therapist may assist in improving her walking and they may help to modify her home and routines to promote safety and independence. The nursing staff provide encouragement and help to motivate her while in hospital to maintain her activities of daily living and her physician provides support and monitoring through evaluating the fracture healing process. The social worker provides information about support systems and works with key family members over the right for older people to take risks and the family’s ability to assist in an unobtrusive monitoring process. Simultaneously, the social worker may be involved in working with the patient on modifying unrealistic expectations about speed and extent of recovery. Rather than identifying tasks, the team, in this scenario, seeks to think about the issues confronting the person before moving on to identify the tasks that relate to working with those issues.

The use of systems and processes that underpin provision of support for complex needs can enable team members to contextualize and link their very different modes of intervention. It will also help them to identify the relationships between the different issues and concerns that patients have to manage. This assists in the provision of integrative care and also enables team members to identify and discuss differences in interpretation of those issues. In the above scenario a discussion might be warranted concerning identification of risk, and whether there is consensus about an acceptable level of risk. Similarly, it would be useful to share and compare views about when each team member would intervene and why. Shared reflection creates learning opportunities for the interprofessional rehabilitation team. In this example it might permit exploration of members’ different ways of defining risk and their emotional responses to the issue of risk assessment, including how this affects older people and how this has implications for service provision.

To provide a further understanding of the skills and expertise of members of the rehabilitation team, organizational factors such as staff availability, rehabilitation resources and networks of communication with other agencies are also required. The development of systematic, reflective and service-user focused practice is not easy, and requires attention to team activities such as discussion, goal setting and decision making. What is of some concern is that rehabilitation professionals may lack training in, and detailed knowledge of, teamwork and group processes. In order to maximize the effectiveness of teamwork, team members need to be able to contribute to a facilitative team process. They need to be able to analyse their contribution to the process as well as evaluate the overall process itself. In addition to this, good teamwork requires solid knowledge about others’ work and roles, as well as the ability to discuss and convey the key dimensions of one’s own role.

Models of successful teamwork in other health settings can be helpful in identifying characteristics to which interprofessional rehabilitation teams might aspire. Boon et al. (2004) for example, describe a conceptual framework for evaluating different types of team practices in the provision of healthcare, focusing on four dimensions: philosophy, structure, process and outcomes. They illustrate how these four dimensions operate along a continuum for different varieties of healthcare teams and these can be characterized according to their degree of integration. By way of example, they suggest that a service user with acute myocardial infarction will benefit most from a team able to respond rapidly. In this situation it is likely that the team philosophy will be very biomedically based and orientated towards saving life, the team structure will comprise highly independent practitioners, team processes relatively rigid and rehearsed, with outcomes measured in terms of mortality. Conversely, a service user with long-term, complex needs (such as an older person experiencing frequent falls living in the community) is likely to benefit from a rehabilitation team that works in a more integrated fashion. Here, the team philosophy will be about maximizing the capabilities of the individual, team structures and processes will be less rigid, and outcomes are likely to be measured in terms of improving quality of life through reducing falls, improving confidence and/or enhancing mobility (or at least minimizing any deterioration in quality of life). So in preference to saying that a fully integrated team is always the ideal, Boon et al. (2004) rather suggest that this framework can help facilitate service users and providers to decide which model suits their needs best.

In another example of designing successful teamwork Wake-Dyster (2001) describes a project undertaken in paediatric services to explain the implementation of teamwork in a number of different child health teams, including a rehabilitation service. Success was attributed to a number of key features including the following:

- A ‘team vision’ and ‘strong commitment to teamwork and patient care improvements’ that were not just focused on clinical goals but provided a sense of accountability within the team for achieving results.

- Processes to guide team development including leaders’ awareness and ‘acceptance of “where staff are at” ’.

- Building of ‘leadership capacity’ and ‘cross-team learning’ with acknowledgement of the need for flexibility.

- Including opportunities for ‘encouragement and to experience success’.

- Awareness of the team’s ‘context and relationship to the organisation’.

(Adapted from Wake-Dyster, 2001, pp. 39–40)

Among the barriers to achieving success were short-term financial constraints that competed with longer-term quality improvements (Wake-Dyster, 2001). As we continue with this chapter you will realize that these are common themes underpinning the creation of successful interprofessional rehabilitation teams.

Research evidence can also help to highlight positive attributes of teams that have an impact on service-user care and recovery. Within the context of stroke rehabilitation for example, Strasser and colleagues (2005) evaluated the perceptions of 530 team members from 46 rehabilitation teams about team functioning on ten dimensions; they explored the association of these with functional improvement, discharge home and length of rehabilitation stay for service users. Three of the ten dimensions were associated with functional improvement, namely: (1) task orientation; (2) order and organization and (3) utility of quality information. One further dimension, team effectiveness, was associated with length of rehabilitation stay in quite a complex way: those teams that had high satisfaction with perceived effectiveness had patients with a longer mean length of stay, suggesting that these teams were better placed to advocate for longer hospitalizations and withstand pressures to discharge patients prematurely. In contrast, teams that had a strong sense of ‘teamness’ (which can be described as a sense of cohesion between team members) showed a trend towards reduced length of stay for their patients. It is not that one team was ‘better’ than the other, rather these results suggest the relationships between team effectiveness, efficiency and various patient outcomes are not straightforward and evaluations of teamwork need to take account of this complexity.

The tensions of working in teams

However, modern day teamwork is not without potential difficulties, for example Burton comments on the tensions between undertaking ‘active therapy’ and ‘care components of nursing care’ for nurses working in stroke units (Burton, 2000, p. 175). When professional boundaries are ‘blurred’ like this, it may be difficult for an individual professional to remain clear that they are operating within their scope of practice. The chapter co-author, Sarah, has developed a technique to overcome these tensions. For example she often starts a conversation by stating from which of her two professional stances she is operating, so as to make it clear from which background or skill set her contribution is coming from. Similarly there may be concerns regarding ‘new types’ of healthcare providers, such as the advanced or extended practice roles for allied health professionals mentioned earlier in this chapter. Murphy (2007) provides an interesting personal account of the medical profession’s ‘fears’ that may be associated with such staff (namely that they will put existing doctors out of a job, will challenge the salaries and status of existing doctors, will result in other shortages in the workforce, or compete for private practice income if they move out of the publically funded service). It is likely that the changes in roles will continue apace because of impending workforce shortages, so Murphy concludes that it is important for doctors to overcome these fears and embrace change or even act as the champions or leaders of change (Murphy, 2007). What is interesting about the medical perspective of Murphy’s article is that it reflects attitudes found by other researchers investigating collaborative practice: that doctors are less positive in their attitude towards teamwork and team training than nurses (Hansson et al., 2010). Further research is required to identify if the reasons for these attitudes lie in undergraduate training or elsewhere, such as in the tension between doctors’ ‘understanding of their professional role and their conditions of work’ (Hansson et al., 2010, p. 84).

Sometimes the interprofessional working that we have been advocating in this book does not fit well with the requirements of professional registration simply because the very nature of interprofessional working is that it is about the overlapping of professional roles and responsibilities. For example, the UK’s Health Professions Council requires professionals to meet standards regarding: character; health; proficiency (core competencies/benchmarked standards of practice); conduct, performance and ethics; and continuing professional development (CPD) (see www.hpc-uk.org/aboutregistration/standards/). There are also standards for education and training of the education providers, these standards relate to undergraduate training as well as CPD accredited courses and activities. However, conflict can arise when a CPD course offered by one professional body is not accepted as ‘accredited’ by a different professional body, which may create barriers to a professional wishing to acquire the skills usually attributed to another profession. The fitting together of standards and requirements for state registration, professional body membership and higher education course validation and accreditation is clearly complex. Some countries, such as the USA, have authorities for overseeing rehabilitation standards to help with this complexity (King et al., 2005).

Cleary these regulatory systems and standards are important for protecting the public. They also provide the basis for professional bodies or employing organizations to offer liability insurance or professional indemnity. This leads our debate on to the tensions and dilemmas that can arise from the legal implications of shared responsibility when practising in an interprofessional team.

Legal responsibilities arising from multidisciplinary meetings are brought into focus in the following example of a study that surveyed doctors’ understanding of their individual accountability during team meetings about the care of patients with cancer (Sidhom and Poulsen, 2008). In the survey a description is given of a patient, aggrieved by a treatment decision made by a team and who wished to seek compensation; the question arising from this situation being who the court would consider responsible for the decision. The survey included questions about whether or not doctors were aware that they were individually accountable for the team decisions and whether the team meetings were conducted in such a way that reflected this individual responsibility. Based in four Australian tertiary care hospitals 18 teams and 136 doctors responded to the survey. It was clear that only 48% of doctors correctly thought they were individually liable; 33% felt that the team meeting environment was suboptimal for making decisions and on those occasions when doctors disagreed with a decision many did not formerly dissent at that time. The study authors concluded that doctors needed to be made aware of the legal implications of participating in multidisciplinary team meetings, with greater awareness of these responsibilities and improvements in the team dynamics being the way to ‘optimize patient outcomes while limiting exposure of participants to legal liability’ (Sidhom and Poulsen, 2008, p. 287). Unfortunately, this study did not involve other healthcare professionals but it does highlight the tensions that can occur within team decision-making situations.

In another study Nugus and colleagues describe how and where clinicians exercise power in their interprofessional relationships (Nugus et al., 2010). In this interactional study of health occupational relations the authors found two distinct types of power: collaborative or negotiated power versus competitive or authoritative power. It was not considered that one type was better but rather to what extent one type would be more appropriate than the other for a given context. The authors comment that the role of healthcare managers is to mediate between policy and practice but it may be that further research is needed to explore ‘the interplay of managers in interprofessional relations, and to the challenges and opportunities of integrating care across formal service boundaries’ (Nugus et al., 2010, p. 908).

Resolving these tensions at an individual level requires reflective practice that includes an awareness of personal and professional limitations and the development of skills for being a life-long learner. These are clearly necessary for keeping up-to-date in professional competencies. Resolving these tensions at a team level requires similar skills on the part of each team member but also processes and procedures within the team to help resolve conflict as well as a leader who knows when and how to move things on. Some of the basic principles for dealing with team conflict have been described by Anderson (2010) and the following is a synopsis of the main points:

- act in a timely way to identify the real points of difference, clarify the facts;

- get team members to resolve their differences, or compromise, based on these facts; or

- be prepared for the team leader to impose a resolution if needed.

Anderson (2010) also notes that not all disagreements are problematic, in fact healthy debate and constructive criticism should be encouraged. Allowing such debate but avoiding stand-offs is easier to achieve if the team is built and run effectively, as it is more likely that there will be trust and confidence in each other to cope with disagreements and any potentially damaging conflict can be dealt with promptly. A final point on this issue is that it may be appropriate to document the resolution and any action plans that arise from it.

Thinking outside the professional box

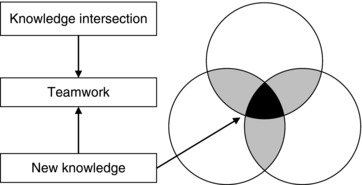

By now our understanding of what makes an effective interprofessional rehabilitation team as well as what tensions need to be overcome, is beginning to take shape. As a core theme for this book we acknowledge the contribution of many rehabilitation professionals, from differing backgrounds, who have informed our thinking, several of whom have been named at the start of this textbook. For example, a presentation given by Kath McPherson at the New Zealand Physiotherapy Conference (in Wellington, 2001) described a Venn diagram showing the intersection, or overlap, between discipline-specific knowledge and how transfer and accumulation of knowledge can lead to the production of deeper knowledge (see Figure 3.1). This deeper knowledge McPherson also describes as the ‘new knowledge’ of the team (McPherson et al., 2001; see also Gibbons et al., 1994).

Figure 3.1 The active intersection of discipline-specific knowledge to produce new, ‘deeper’ knowledge of an interprofessional team. (Adapted and reproduced with permission from Kath McPherson.)