Chapter 115 Computer Navigation in Primary Total Knee Arthroplasty

Numerous authors have investigated outcomes following total knee arthroplasty (TKA), finding that malalignment greater than 3 degrees resulted in a significantly higher potential for mechanical loosening and implant failure. Petersen and Engh investigated the radiographic results of 50 patients who underwent primary TKA with conventional methods, noting a 26% failure to achieve alignment within the optimum of 3 degrees of varus or valgus from the mechanical axis.34 Jeffery and associates noted satisfactory postoperative coronal alignment (mechanical axis deviation less than 3 degrees) in 68% of their TKAs. In operated knees with mechanical axis deviation greater than 3 degrees in the coronal plane, a mechanical loosening rate of 24% occurred at 8 years, as opposed to 3% mechanical loosening for normally aligned knees.16 Berend and colleagues investigated tibial component failure mechanisms, noting that malalignment of the tibial component at more than 3 degrees of varus increased the odds of failure.4

Computer-assisted navigation of TKA has been shown to produce improved mechanical axis alignment in the clinical setting and offers significant advantages, particularly in cases with severe deformity resulting from long-standing arthritis or traumatic causes.* Access to bony landmarks with open procedures has made TKA navigation a very feasible system when imageless referencing protocols are used. After the original navigation system was developed in 1991 by Dr. Stephane Lavallee at the University of Grenoble for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction, Saragaglia and coworkers introduced the first kinematic navigation protocol for determining the centers of the hip and ankle; this paved the way for a reproducible and simple imageless approach.38 Optical tracking has been the primary data accrual method for most current systems.1,8,11,13,26 This review discusses the basis of that technology, clinical methods, and outcomes offered by current methods of computer navigation in TKA. Additionally, problem areas that have shown limited acceptance of this technology are addressed by the introduction of a system that makes navigation a simple and limited surgical tool customized to the individual needs of each surgeon.

Components of a Computer Navigation System

Tracking Technologies

Optical tracking systems require two or three CCD cameras to pick up laser impulses from the trackers that are recognized by a minimum of three and possibly four or five active emitters or passive reflective balls. The computer calculates the three-dimensional position of the trackers based on recognition of the spatial footprint of the tracker emitters. The footprint of each tracker is unique and allows differentiation of bones, instruments, and implants. Conventional optical cameras function by being placed 6 to 8 feet from the object trackers, and must have an unobstructed “line of sight” to the trackers. This requires that operating personnel must be aware of this relationship, but if positioning is optimal, staff readily adapt to the requirement. Clinical validation studies of optical tracking systems have demonstrated very high reliability and accuracy with a typical translational error of 0.25 mm.23,35,52 This absolute measurement error increases trigonometrically with increasing distance from the camera.43

Electromagnetic (EM) tracking relies on small trackers that create an electromagnetic impulse that is recognized by an electromagnetic coil placed 20 to 30 inches away.29 These trackers may be placed inside the wound but require small wires that go directly to the computer system for activation. The magnetic coil then measures interference created by the tracker as it moves within the electromagnetic field. The disadvantage of current electromagnetic tracking systems is distortion of the field created by ferrous metals that are inherently magnetic, but any metal such as brass and copper and even nonmetals such as Kevlar may interfere. Current computer algorithms have been calibrated to shut down the system if distortion is recognized. However, the EM approach still remains vulnerable to many other potentially distorting fields that are found in the typical operating room. Clinical validation studies have identified this problem, and although the electromagnetic system seems to perform with the precision of current optical systems at the 0.5 mm level, the occasional outlier may be off by several degrees, which makes this method less reliable.1,11,13,24

Referencing Methods

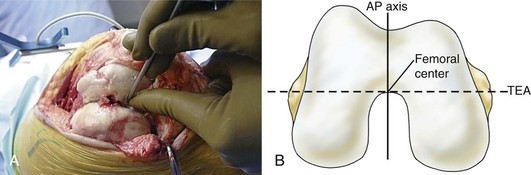

For the surgeon, referencing of target objects is the most significant problem and requires a thorough knowledge of both the technology and the desired anatomic points to be matched on the virtual computer model. The process basically is to define points in space with a tracker that can be triangulated by the tracking system. For surgical instruments, a referencing tool allows the surgeon to capture the “marked” instrument such as a pointer probe. The precision of the instrument will be within 250 to 500 µ of error.23 Imageless referencing is possible if the targeted objects are directly visible, and is most applicable in TKA. Numerous studies have demonstrated the efficacy of imageless referencing as compared with conventional instrumentation for TKA, but these results depend on the expertise of the surgeon to choose the correct reference points.19 Computer algorithms are written with the assumption that the ideal point will be selected. For example, referencing of one universal total knee protocol prescribes that the femoral center is chosen as a point that is under the roof of the intercondylar notch and lies on both the transepicondylar line and the anteroposterior axis of Whiteside. Deviation from this “ideal” point adds error.

Kinematic referencing in TKA as pioneered by Lavallee has been a novel innovation for determining the center of the hip and ankle joints, markedly simplifying this procedure.38 Because the hip joint is not directly visible, a method was needed by which to accurately reference the hip center. This was accomplished by tracking the femur with the optical camera as the femur was rotated in a circular motion. The movement of the tracker described the base of a cone, which when projected to its zenith closely approximates the center of the hip joint. The computer algorithm calculates the root mean square error or the standard deviation, which must fall within a limited range for the computer to accept the hip center reference point.

A secondary method of referencing is bone morphing, which involves selecting hundreds of surface match points by “painting” the bone with the pointer probe.46,47 This method does not require the segmented three-dimensional model typical of computed tomography (CT) but uses a virtual model that is then constructed by the computer algorithm. The virtual image created allows enhanced capabilities such as prosthetic sizing, “live” bone resection, and kinematic assessment. However, this additional technology usually adds time and complexity to the operative procedure and may limit the surgeon’s choice of prosthetic implants. One current morph technology is to limit the referenced areas to small patches. For example, surgeons find difficulty referencing the femoral posterior condyle in finding the most posterior or dorsal position. This process can be simplified and made much more precise by morphing a small patch, allowing the computer to find the optimum position.

Ultrasound image capture is a newer method of referencing that is evolving as a potential technique whereby multimodal referencing is performed.8,26 Depending on frequency and the acoustical properties of the object, point localization is accurate to submillimeter levels on the order of 0.25 to 0.75 mm with ultrasound, whether it is 2-dimensional, 2.5-dimensional, or 3-dimensional in the modality of image capture. Segmentation is possible when this image may be matched with a preoperative CT image or even an intraoperative “bone morphed” image. However, the clinical applications remain limited for a variety of reasons. Definition of baseline anatomic points is difficult with ultrasound, which creates an error on the order of 2 to 5 mm, which is unacceptable for clinical practice. However, the promise of ultrasound is that it can be done through the tissues intraoperatively without the need for skin incision or radiation exposure.

Clinical Methods

The specifics of navigation referencing constitute an important element of the technique and bear detailed description. Tracker placement requires rigid fixation of the dynamic reference base to the femur and tibia, because any movement creates error. Current systems have validation check points that may be established and then remeasured throughout the procedure to monitor tracker error. Recent studies have favored two pins of 3 mm diameter.28 It is important to note that single pins of 5 mm and bicortical placement should be avoided, as incidental fractures have been described. Placement of the femoral pins in the medial femoral condyle or in a percutaneous transepicondylar position avoids the potential for neurovascular injury43 (Fig. 115-1). Hip center determination is done using the kinematic method originally described by Saragaglia et al.38

Anatomic referencing of the patient’s landmark, the most critical step for the surgeon, requires a thorough understanding of what the system’s software engineers had in mind when they designed the system. This becomes the most likely source of error. For typical referencing, the computer definition of the femoral center is a point under the roof of the intercondylar notch that is in the middle of the intercondylar notch and lies in the anteroposterior axis of Whiteside (Fig. 115-2). From dissections, this point also lies directly on the transepicondylar axis of the distal femur. The surgical epicondyle depression is the reference for the medial epicondyle, and the lateral epicondyle is the most prominent point of that landmark.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree