Component Removal

Ian Barrett

Ryan Martin

Rafael J. Sierra

INDICATIONS/CONTRAINDICATIONS

The most common reason for removal of well-fixed components in total hip arthroplasty (THA) is infection. Other important indications for component removal include malpositioned implants causing pain or instability, wear and osteolysis, and adverse local tissue reactions related to metal on metal hip systems where a monoblock cup or modular stem requires removal.

There are no contraindications to component removal. Removal of well-fixed implants, either cemented or uncemented, should be weighed against component retention. For the treatment of infection, the benefit is obvious; however, in other cases, the surgeon should carefully consider the effect of component removal and the likelihood of obtaining another well-fixed implant in the remaining bone. The potential challenges of removing a well-fixed component include bone loss, fracture, increased surgical time, and increased cost. Specifically, the surgeon should pay special attention to the remaining bone stock. On the acetabular side, the surgeon should note how medially the acetabular component was placed and the potential for medial wall perforation or pelvic discontinuity when attempting removal. On the femoral side, the challenge exists when removing well-fixed uncemented implants in the presence of very thin cortices. The surgeon should aim to retain well-fixed, well-positioned implants that allow for restoration or offset and leg lengths and stability with the use of modular components.

Well-fixed Femoral Components

Removal of a well-fixed femoral component may be required:

In the presence of infection

With instability secondary to femoral component malposition

If unable to obtain a stable implant or appropriate soft tissue tension using modular head extensions because of the new position of a revised acetabular component

In the presence of significant proximal femoral osteolysis and a well-fixed femoral component that has the potential for subsequent failure

If nonmodular femoral components are in place and the existing femoral head is small and does not allow placement of a bipolar device (i.e., construction of a tripolar)

When the damage of the trunnion or taper is so severe that placing a new femoral head would be unacceptable

In the presence of corrosion and adverse tissue reactions to modular neck implants

For exposure of the acetabulum in the case of a monoblock femoral component

A malpositioned (excessively anteverted or retroverted) femoral component that is causing instability almost always requires removal because it is difficult to compensate for this problem by other means. To determine whether a malrotated stem is the cause of instability, the surgeon must determine intraoperatively both the version of the stem and its combined version with the acetabulum. The surgeon should also consider the modularity of the system already in place when deciding to revise a well-fixed femoral component. In addition, in cases where both the acetabular and femoral components are malpositioned, it might be easier to revise the well-fixed acetabular component before attempting removal of the well-fixed femoral component.

A well-fixed nonmodular component occasionally presents problems for the hip surgeon. For one, nonmodular heads cannot be changed and may limit the ability to adjust the length and offset

necessary to create a stable construct. This difficulty can be somewhat overcome with the use of specialized liners (lipped, oblique, offset, eccentric) or if the head allows for the placement of a bipolar component (to create a tripolar design). Secondly, in the absence of the ability to exchange parts, significant damage to the taper is an indication to remove a well-fixed component as it may adversely affect the new femoral head.

necessary to create a stable construct. This difficulty can be somewhat overcome with the use of specialized liners (lipped, oblique, offset, eccentric) or if the head allows for the placement of a bipolar component (to create a tripolar design). Secondly, in the absence of the ability to exchange parts, significant damage to the taper is an indication to remove a well-fixed component as it may adversely affect the new femoral head.

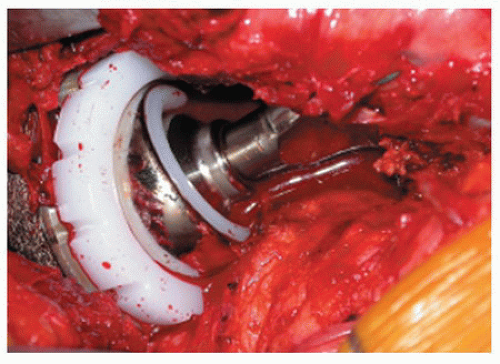

Modular technology provides greater flexibility when dealing with a well-fixed femoral stem if it is in acceptable position; however, there are still circumstances in which the surgeon may still choose to revise the component. One such circumstance is when a larger diameter femoral head (greater than or equal to 36 mm) is favored due to a lower risk of dislocation and may not be compatible with the present taper. In these cases, the surgeon may consider using a tripolar construct to provide a large-diameter articulation (Fig. 22-1).

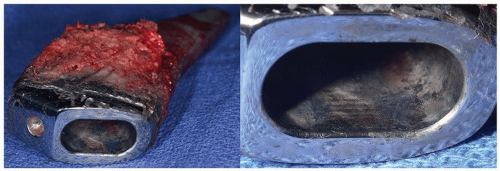

Well-fixed femoral components may require revision in the presence of adverse local soft tissue reactions. These can occur secondary to corrosion of a cobalt-chromium femoral head on a titanium stem or from the taper body junction of a titanium femoral component with a cobalt-chromium modular neck as seen in Figure 22-2.

Well-fixed Acetabular Components

Much like on the femoral side, the decision to retain or replace a well-fixed acetabular component requires careful consideration of the trade-offs in construct stability.

Several series have demonstrated that cemented all-polyethylene acetabular components in good position can be retained without substantially increasing the subsequent revision rate; however, a majority of surgeons opt to replace these components during revision surgery (4). The reasons for this decision are likely twofold. For one, retaining the cup limits the ability to upsize the femoral head diameter. Secondly, these cemented components can generally be removed efficiently and with minimal disruption to the surrounding osseous structures.

Removal of the well-fixed acetabular component should be considered when:

There is presence of infection.

There is metal on metal failure in a hip resurfacing or THA and the monoblock cup requires removal.

There is a malpositioned acetabular component leading to the following:

Instability

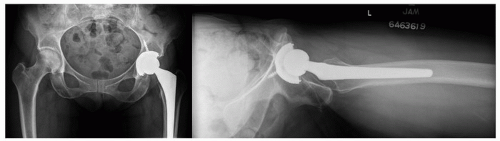

Iliopsoas impingement (Fig. 22-3)

Excessive polyethylene wear

Ceramic liner fractures or squeaking

Revision is required secondary to osteolysis, bearing wear or femoral component loosening, and the acetabular component may not accommodate (cementing or locking) a polyethylene insert and use of a larger femoral head (uncommon today).

Severe osteolysis is present, and leaving the cup may risk subsequent failure and revision. This is especially important in first-generation uncemented cups with poor track records.

The first consideration in these cases is component position. Components that are malpositioned (version or inclination) should be removed as they are associated with a higher rate of instability and wear and ultimately component loosening (5,6,7). While component inclination can be accurately determined utilizing standard AP radiographs of the hip, measurement of acetabular version from preoperative radiographs can be more challenging and less consistent. Preoperative CT remains the gold standard for confirmation of suspected implant malposition; however, recent studies utilizing computer-based 2D/3D reconstruction techniques performed on radiographs alone may provide a good alternative (8,9,10,11). The next most important factor to consider is the availability of replacement liners for the implanted cup. Finding a matched liner can be problematic with older style implants. A mismatched liner can be cemented into a well-fixed cup if necessary although this may not be possible with small-diameter, shallow, or thick-walled acetabular cups (12,13). Also important to consider is whether the implanted cup has any known design problems. Early cups with noncongruent polyethylene designs or known locking mechanism shortcomings have been associated with significant backside wear, osteolysis, and early failure (14). In these cases, it may be advisable to proceed with cementing in a new liner or cup revision. Cups with a documented history of poor intermediate- or long-term survival (such as some first-generation HA cups) should also be considered for revision.

If significant osteolysis is present, this further complicates the decision to retain or remove a well-fixed uncemented cup. Although such cups can be easily removed with modern techniques, the remaining bone may have large segmental defects that can make subsequent reconstruction very difficult. Research from the Rush and the Mayo groups demonstrates good results with retention of well-fixed cups in the presence of significant periacetabular osteolysis. In situations where removal of the cup is critical to construct stability, good results may be obtained with cup retention and bone grafting with the use of the “trapdoor” technique (15,16). In this technique, a rectangular window is made in the bone approximately 2 cm superior to the retained component in order to create access to debride and bone graft lesions both anterior and posterior to the cup. Following completion of grafting, the rectangular cortical segment can be replaced and then rotated 90 degrees to help contain the graft material.

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree